Popular Viennese Electronic Music, 1990–2015 a Cultural History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Record Store Day 2020 (GSA) - 18.04.2020 | (Stand: 05.03.2020)

Record Store Day 2020 (GSA) - 18.04.2020 | (Stand: 05.03.2020) Vertrieb Interpret Titel Info Format Inhalt Label Genre Artikelnummer UPC/EAN AT+CH (ja/nein/über wen?) Exclusive Record Store Day version pressed on 7" picture disc! Top song on Billboard's 375Media Ace Of Base The Sign 7" 1 !K7 Pop SI 174427 730003726071 D 1994 Year End Chart. [ENG]Pink heavyweight 180 gram audiophile double vinyl LP. Not previously released on vinyl. 'Nam Myo Ho Ren Ge Kyo' was first released on CD only in 2007 by Ace Fu SPACE AGE 375MEDIA ACID MOTHERS TEMPLE NAM MYO HO REN GE KYO (RSD PINK VINYL) LP 2 PSYDEL 139791 5023693106519 AT: 375 / CH: Irascible Records and now re-mastered by John Rivers at Woodbine Street Studio especially for RECORDINGS vinyl Out of print on vinyl since 1984, FIRST official vinyl reissue since 1984 -Chet Baker (1929 - 1988) was an American jazz trumpeter, actor and vocalist that needs little introduction. This reissue was remastered by Peter Brussee (Herman Brood) and is featuring the original album cover shot by Hans Harzheim (Pharoah Sanders, Coltrane & TIDAL WAVES 375MEDIA BAKER, CHET MR. B LP 1 JAZZ 139267 0752505992549 AT: 375 / CH: Irascible Sun Ra). Also included are the original liner notes from jazz writer Wim Van Eyle and MUSIC two bonus tracks that were not on the original vinyl release. This reissue comes as a deluxe 180g vinyl edition with obi strip_released exclusively for Record Store Day (UK & Europe) 2020. * Record Store Day 2020 Exclusive Release.* Features new artwork* LP pressed on pink vinyl & housed in a gatefold jacket Limited to 500 copies//Last Tango in Paris" is a 1972 film directed by Bernardo Bertolucci, saxplayer Gato Barbieri' did realize the soundtrack. -

Resolution May/June 08 V7.4.Indd

craft Horn and Downes briefl y joined legendary prog- rock band Yes, before Trevor quit to pursue his career as a producer. Dollar and ABC won him chart success, with ABC’s The Lexicon Of Love giving the producer his fi rst UK No.1 album. He produced Malcolm McLaren and introduced the hitherto-underground world of scratching and rapping to a wider audience, then went on to produce Yes’ biggest chart success ever with the classic Owner Of A Lonely Heart from the album 90125 — No.1 in the US Hot 100. Horn and his production team of arranger Anne Dudley, engineer Gary Langan and programmer JJ Jeczalik morphed into electronic group Art Of Noise, recording startlingly unusual-sounding songs like Beat Box and Close To The Edit. In 1984 Trevor pulled all these elements together when he produced the epic album Welcome To The Pleasuredome for Liverpudlian bad-boys Frankie Goes To Hollywood. When Trevor met his wife, Jill Sinclair, her brother John ran a studio called Sarm. Horn worked there for several years, the couple later bought the Island Records-owned Basing Street Studios complex and renamed it Sarm West. They started the ZTT imprint, to which many of his artists such as FGTH were signed, and the pair eventually owned the whole gamut of production process: four recording facilities, rehearsal and rental companies, a publisher (Perfect Songs), engineer and producer management and record label. A complete Horn discography would fi ll the pages of Resolution dedicated to this interview, but other artists Trevor has produced include Grace Jones, Propaganda, Pet Shop Boys, Band Aid, Cher, Godley and Creme, Paul McCartney, Tina Turner, Tom Jones, Rod Stewart, David Coverdale, Simple Minds, Spandau Ballet, Eros Ramazzotti, Mike Oldfi eld, Marc Almond, Charlotte Church, t.A.T.u, LeAnn Rimes, Lisa Stansfi eld, Belle & Sebastian and Seal. -

Effets & Gestes En Métropole Toulousaine > Mensuel D

INTRAMUROSEffets & gestes en métropole toulousaine > Mensuel d’information culturelle / n°383 / gratuit / septembre 2013 / www.intratoulouse.com 2 THIERRY SUC & RAPAS /BIENVENUE CHEZ MOI présentent CALOGERO STANISLAS KAREN BRUNON ELSA FOURLON PHILLIPE UMINSKI Éditorial > One more time V D’après une histoire originale de Marie Bastide V © D. R. l est des mystères insondables. Des com- pouvons estimer que quelques marques de portements incompréhensibles. Des gratitude peuvent être justifiées… Au lieu Ichoses pour lesquelles, arrivé à un certain de cela, c’est souvent l’ostracisme qui pré- cap de la vie, l’on aimerait trouver — à dé- domine chez certains des acteurs culturels faut de réponses — des raisons. Des atti- du cru qui se reconnaîtront. tudes à vous faire passer comme étranger en votre pays! Il faut le dire tout de même, Cependant ne généralisons pas, ce en deux décennies d’édition et de prosély- serait tomber dans la victimisation et je laisse tisme culturel, il y a de côté-ci de la Ga- cet art aux politiques de tous poils, plus ha- ronne des décideurs/acteurs qui nous biles que moi dans cet exercice. D’autant toisent quand ils ne nous méprisent pas tout plus que d’autres dans le métier, des atta- simplement : des organisateurs, des musi- ché(e)s de presse des responsables de ciens, des responsables culturels, des théâ- com’… ont bien compris l’utilité et la néces- treux, des associatifs… tout un beau monde sité d’un média tel que le nôtre, justement ni qui n’accorde aucune reconnaissance à inféodé ni soumis, ce qui lui permet une li- photo © Lisa Roze notre entreprise (au demeurant indépen- berté d’écriture et de publicité (dans le réel dante et non subventionnée). -

Traditional Funk: an Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio

University of Dayton eCommons Honors Theses University Honors Program 4-26-2020 Traditional Funk: An Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio Caleb G. Vanden Eynden University of Dayton Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/uhp_theses eCommons Citation Vanden Eynden, Caleb G., "Traditional Funk: An Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio" (2020). Honors Theses. 289. https://ecommons.udayton.edu/uhp_theses/289 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the University Honors Program at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Traditional Funk: An Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio Honors Thesis Caleb G. Vanden Eynden Department: Music Advisor: Samuel N. Dorf, Ph.D. April 2020 Traditional Funk: An Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio Honors Thesis Caleb G. Vanden Eynden Department: Music Advisor: Samuel N. Dorf, Ph.D. April 2020 Abstract Recognized nationally as the funk capital of the world, Dayton, Ohio takes credit for birthing important funk groups (i.e. Ohio Players, Zapp, Heatwave, and Lakeside) during the 1970s and 80s. Through a combination of ethnographic and archival research, this paper offers a pedagogical approach to Dayton funk, rooted in the styles and works of the city’s funk legacy. Drawing from fieldwork with Dayton funk musicians completed over the summer of 2019 and pedagogical theories of including black music in the school curriculum, this paper presents a pedagogical model for funk instruction that introduces the ingredients of funk (instrumentation, form, groove, and vocals) in order to enable secondary school music programs to create their own funk rooted in local history. -

Glastonburyminiguide.Pdf

GLASTONBURY 2003 MAP Produced by Guardian Development Cover illustrations: John & Wendy Map data: Simmons Aerofilms MAP MARKET AREA INTRODUCTION GETA LOAD OF THIS... Welcome to Glastonbury 2003 and to the official Glastonbury Festival Mini-Guide. This special edition of the Guardian’s weekly TV and entertainments listings magazine contains all the information you need for a successful and stress-free festival. The Mini-Guide contains comprehensive listings for all the main stages, plus the pick of the acts at Green Fields, Lost and Cabaret Stages, and advice on where to find the best of the weird and wonderful happenings throughout the festival. There are also tips on the bands you shouldn’t miss, a rundown of the many bars dotted around the site, fold-out maps to help you get to grips with the 600 acres of space, and practical advice on everything from lost property to keeping healthy. Additional free copies of this Mini-Guide can be picked up from the Guardian newsstand in the market, the festival information points or the Workers Beer Co bars. To help you keep in touch with all the news from Glastonbury and beyond, the Guardian and Observer are being sold by vendors and from the newsstands at a specially discounted price during the festival . Whatever you want from Glastonbury, we hope this Mini-Guide will help you make the most of it. Have a great festival. Watt Andy Illustration: ESSENTIAL INFORMATION INFORMATION POINTS hygiene. Make sure you wash MONEY give a description. If you lose There are five information your hands after going to the loo The NatWest bank is near the your children, ask for advice points where you can get local, and before eating. -

Q:How Did You Get Involved with Music? How Did It First Start for You?

Q:How did you get involved with music? How did it first start for you? A:Usually like anyone else, I listened to music on the radio. After some time I found some stuff that I liked most and that was around 1983..85, when producers just started to make special 12 inch mixes of normal radio play version of a song. So I thought that’s quite interesting. Later in the ‘80s, some bands were coming up with special, different sounds, like S-Express, Bomb The Bass, Inner City and stuff like that. This was stuff that I started with. After one or two years more, around 1990 I started buying some underground "club" records, but that was when the party scene over here first started. I went to some of these parties and the clubs and I tried to find out what kind of music they were playing, because the music was very different from what you heard in the daytime. I tried to find the records, it took some time, but finally I was able to find them and after a few years time, I started DJing with this "backstock". Q: How did you start producing? A: First I was a record collector for some years, then I thought `there are many common things in a lot of these records... ´. So they must have mostly similar equipment. I was interested more the backgrounds, trying to get some of this equipment. But at the time in ’93 or ’94 it was very difficult to get, even in Germany because it was totally sold out early ‘80s stuff, like the Roland machines, and analog synths, and the people who owned it didn’t want to sell it. -

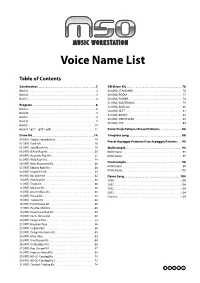

M50 Voice Name List

Voice Name List Table of Contents Combination . .2 GM Drum Kit . 76 Bank A. .2 48 (GM): STANDARD . 76 Bank B. .3 49 (GM): ROOM . 77 Bank C. .4 50 (GM): POWER. 78 51 (GM): ELECTRONIC . 79 Program . .6 52 (GM): ANALOG . 80 Bank A. .6 53 (GM): JAZZ . 81 Bank B. .7 54 (GM): BRUSH . 82 Bank C. .8 55 (GM): ORCHESTRA. 83 Bank D . .9 56 (GM): SFX . 84 Bank E . 10 Bank G / g(1)…g(9) / g(d). 11 Drum Track Patterns/Preset Patterns. 86 Drum Kit . .14 Template song . 88 00 (INT): Studio Standard Kit. 14 Preset Arpeggio Patterns/User Arpeggio Patterns . 90 01 (INT): Funk Kit. 16 02 (INT): Jazz/Brush Kit . 18 Multisample. 94 03 (INT): B.Real Rap Kit . 20 ROM mono . 94 04 (INT): Acoustic Pop Kit. 22 ROM stereo . 97 05 (INT): Wild Rock Kit . 24 Drumsample . 98 06 (INT): New Processed Kit. 26 07 (INT): Electro Rock Kit . 28 ROM mono . 98 08 (INT): Insane FX Kit . 30 ROM stereo . 103 09 (INT): Nu Style Kit . 32 Demo Song. 104 10 (INT): Hip Hop Kit . 34 S000 . 104 11 (INT): Tricki kit. 36 S001 . 104 12 (INT): Mashed Kit. 38 S002 . 104 13 (INT): Drum'n'Bass Kit . 40 S003 . 104 14 (INT): House Kit . 42 Cue List . 104 15 (INT): Trance Kit . 44 16 (INT): Hard House Kit . 46 17 (INT): Psycho-Chill Kit . 48 18 (INT): Down Low Rap Kit. 50 19 (INT): Orch.-Ethnic Kit . 52 20 (INT): Original Perc . 54 21 (INT): Brazilian Perc. 56 22 (INT): Cuban Perc . -

Idioms-And-Expressions.Pdf

Idioms and Expressions by David Holmes A method for learning and remembering idioms and expressions I wrote this model as a teaching device during the time I was working in Bangkok, Thai- land, as a legal editor and language consultant, with one of the Big Four Legal and Tax companies, KPMG (during my afternoon job) after teaching at the university. When I had no legal documents to edit and no individual advising to do (which was quite frequently) I would sit at my desk, (like some old character out of a Charles Dickens’ novel) and prepare language materials to be used for helping professionals who had learned English as a second language—for even up to fifteen years in school—but who were still unable to follow a movie in English, understand the World News on TV, or converse in a colloquial style, because they’d never had a chance to hear and learn com- mon, everyday expressions such as, “It’s a done deal!” or “Drop whatever you’re doing.” Because misunderstandings of such idioms and expressions frequently caused miscom- munication between our management teams and foreign clients, I was asked to try to as- sist. I am happy to be able to share the materials that follow, such as they are, in the hope that they may be of some use and benefit to others. The simple teaching device I used was three-fold: 1. Make a note of an idiom/expression 2. Define and explain it in understandable words (including synonyms.) 3. Give at least three sample sentences to illustrate how the expression is used in context. -

Falco Nachtflug Mp3, Flac, Wma

Falco Nachtflug mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock / Pop Album: Nachtflug Country: Indonesia Released: 1992 Style: Pop Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1345 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1502 mb WMA version RAR size: 1585 mb Rating: 4.6 Votes: 485 Other Formats: MMF XM DXD VOX AAC FLAC AU Tracklist A1 Titanic 3:35 A2 Monarchy Now 4:12 A3 Dance Mephisto 3:31 A4 Psychos 3:16 A5 S.C.A.N.D.A.L. 3:56 B1 Yah - Vibration 3:33 B2 Propaganda 3:36 B3 Time 4:07 B4 Cadillac Hotel 5:07 B5 Nachtflug 3:15 Credits Acoustic Guitar, Guitar [Electric] – Bert Meulendijk Art Direction – Hannes Rossbacher* Engineer [Additional] – John "Zorba" Kriek* Engineer, Programmed By, Keyboards [Additional], Sampler – Hans "Woody" Weekhout* Keyboards, Synthesizer, Sampler, Bass, Percussion, Piano [Grand], Backing Vocals – Rob Bolland & Ferdi Bolland* Lyrics By, Directed By – Falco Photography By [Booklet] – Claudia Kleefeld Photography By [Cover] – Curt Themessl Producer, Arranged By, Mixed By – Bolland & Bolland Trumpet – Jan Hollander Notes Manufactured And Printed In Indonesia. Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 0 777 7 80322 4 3 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year 1C 568-0777 7 1C 568-0777 7 Nachtflug (CD, Electrola, EMI 80322 2 9, 7 Falco 80322 2 9, 7 Germany 1992 Album) Electrola GmbH 80322 2 80322 2 Nachtflug (Cass, Not On Label none Falco none Bulgaria Unknown Album, Unofficial) (Falco) Nachtflug (10xFile, none Falco Electrola none Austria 2003 MP3, Album, 256) Nachtflug (Cass, EMI Electrola 7 80322 4 Falco 7 80322 4 Germany 1993 Album) GmbH Nachtflug (Cass, 2007 Falco Tak! Cassette 2007 Poland 1992 Album) Related Music albums to Nachtflug by Falco Bolland & Bolland - Broadcast News (The World Is Burning) Bolland & Bolland - Mexico, I Can't Say Goodbye Bolland & Bolland - The Best Of Bolland & Bolland David Vermeulen - David Vermeulen Falco - The Remix Hit Collection Falco - 3 Falco - Do It Again BED - Vleugels Falco - Emotional Bolland & Bolland - Bolland & Bolland Falco - Wiener Blut Cj Bolland - The prophet. -

Bomb the Bass

BOMB THE BASS 7" SINGLES Beat Dis/Beat Dis(Dub) Rhythm King DOOD 1 01/88 Don't Make Me Wait/Megablast Rhythm King DOOD 2 08/88 Say A Little Prayer/10 Seconds To Terminate Rhythm King DOOD 3 11/88 Say A Little Prayer/10 Seconds To Terminate Rhythm King DOOD 3SP 11/88 [packaged 7" with sticker and poster] Love So True/You See Me In 3D Rhythm King DOOD 4 01/91 Winter In July(7")/Dune Buggy Attack Rhythm King/Epic 657 275-7 07/91 12" SINGLES Beat Dis(Extended Dis)/Beat Dis(Radio Edit)/Beat Dis (Bonus Beats) Rhythm King DOOD 121 01/88 Beat Dis(Gangster Boogie Inc. Remix)/Beat Dis(Edit)/ Beat Dis(Dub) Rhythm King DOODR121 02/88 Don't Make Me Wait/Megablast Rhythm King DOOD 122 08/88 Don't Make Me Wait(Maximum Frequency Mix)/ Megablast Rap(Version) Rhythm King DOODR122 08/88 Say A Little Prayer/10 Seconds To Terminate Rhythm King DOOD 123 11/88 Say A Little Prayer(Get Down And Pray)/Megamix/10 Seconds To Terminate(Live) Rhythm King DOODR123 12/88 Love So True/You See Me In 3D/Understand This Rhythm King DOOD 124 01/91 Winter In July(Cosmic Jammer Club Mix)/Winter In July(Ubiquity Mix)/Winter In July(Brighton Daze Mix)/ You See Me In 3D(Remix) Rhythm King/Epic 657 275-6 07/91 Bug Powder Dust 4th & Broadway 12BRW 300 ??/94 Darkheart(Album Mix)/Darkheart(The Darker Side)/ Darkheart(Alpha & Omega #1)/Darkheart(Sabres Of Paradise Main Mix)/Darkheart(Sabres Of Paradise Second Mix) 4th & Broadway 12BRW 305 ??/94 1 To 1 Religion(Extended Club Mix)/1 To 1 Religion (The Simenon/Dom T Remix)/1 To 1 Religion(White Knuckle Remix)/1 To 1 Religion(Space Funk Mix)/ 1 To 1 Religion(Mr Lawrence Mix)/1 To 1 Religion (DJ Pogo Remix) 4th & Broadway 12BRW 313 ??/95 Butterfingers(Original Version)[5:33]/Butterfingers(Dan Aykroyd Mix)[3:23]/Butterfingers(Adam Sky Ravebummer Mix)[7:11] K7 Records K7234EP 11/08 [limited edition] CASSETTE SINGLES Love So True/You See Me In 3D Rhythm King DOOD 4C 01/91 Winter In July Rhythm King/Epic 657 275-4 07/91 CD SINGLES Beat Dis(Extended)/Beat Dis(Radio Edit)/Beat Dis (Bonus Beats)/Beat Dis(Gangster Boogie Inc. -

Access the Best in Music. a Digital Version of Every Issue, Featuring: Cover Stories

Bulletin YOUR DAILY ENTERTAINMENT NEWS UPDATE MARCH 23, 2020 Page 1 of 27 INSIDE Lil Uzi Vert’s ‘Eternal Atake’ Spends • Roddy Ricch’s Second Week at No. 1 on ‘The Box’ Leads Hot 100 for 11th Week, Billboard 200 Albums Chart Harry Styles’ ‘Adore You’ Hits Top 10 BY KEITH CAULFIELD • What More Can (Or Should) Congress Do Lil Uzi Vert’s Eternal Atake secures a second week No. 1 for its first two frames on the charts dated Dec. to Support the Music at No. 1 on the Billboard 200 albums chart, as the set 28, 2019 and Jan. 4, 2020. Community Amid earned 247,000 equivalent album units in the U.S. in Eternal Atake would have most likely held at No. Coronavirus? the week ending March 19, according to Nielsen Mu- 1 for a second week without the help of its deluxe • Paradigm sic/MRC Data. That’s down just 14% compared to its reissue. Even if the album had declined by 70% in its Implements debut atop the list a week ago with 288,000 units. second week, it still would have ranked ahead of the Layoffs, Paycuts The small second-week decline is owed to the chart’s No. 2 album, Lil Baby’s former No. 1 My Turn Amid Coronavirus album’s surprise reissue on March 13, when a new (77,000 units). The latter set climbs two rungs, despite Shutdown deluxe edition arrived with 14 additional songs, a 27% decline in units for the week.Bad Bunny’s • Cost of expanding upon the original 18-song set. -

Austrian Rap Music and Sonic Reproducibility by Edward

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ETD - Electronic Theses & Dissertations The Poetic Loop: Austrian Rap Music and Sonic Reproducibility By Edward C. Dawson Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in German May 11, 2018 Nashville, Tennessee Approved: Christoph M. Zeller, Ph.D. Lutz P. Koepnick, Ph.D. Philip J. McFarland, Ph.D. Joy H. Calico, Ph.D. Copyright © 2018 by Edward Clark Dawson All Rights Reserved ii For Abby, who has loved “the old boom bap” from birth, and whose favorite song is discussed on pages 109-121, and For Margaret, who will surely express a similar appreciation once she learns to speak. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This work would not have been possible without an Ernst Mach Fellowship from the Austrian Exchange Service (OeAD), which allowed me to spend the 2015-16 year conducting research in Vienna. I would like to thank Annagret Pelz for her support, as well as all the participants in the 2015-2016 Franz Werfel Seminar, whose feedback and suggestions were invaluable, especially Caroline Kita and organizers Michael Rohrwasser and Constanze Fliedl. During my time in Vienna, I had the opportunity to learn about Austrian rap from a number of artists and practitioners, and would like to thank Flip and Huckey of Texta, Millionen Keys, and DJ Taekwondo. A special thank you to Tibor Valyi-Nagy for attending shows with me and drawing my attention to connections I otherwise would have missed.