Total of 10 Pages Only May Be Xeroxed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Translocation and Transport

Glime, J. M. 2017. Nutrient Relations: Translocation and Transport. Chapt. 8-5. In: Glime, J. M. Bryophyte Ecology. Volume 1. 8-5-1 Physiological Ecology. Ebook sponsored by Michigan Technological University and the International Association of Bryologists. Last updated 17 July 2020 and available at <http://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/bryophyte-ecology/>. CHAPTER 8-5 NUTRIENT RELATIONS: TRANSLOCATION AND TRANSPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS Translocation and Transport ................................................................................................................................ 8-5-2 Movement from Older to Younger Tissues .................................................................................................. 8-5-6 Directional Differences ................................................................................................................................ 8-5-8 Species Differences ...................................................................................................................................... 8-5-8 Mechanisms of Transport .................................................................................................................................... 8-5-9 Source to Sink? ............................................................................................................................................ 8-5-9 Enrichment Effects ..................................................................................................................................... 8-5-10 Internal Transport -

NEW DATA ABOUT MOSSES on the SVALBARD GLACIERS Olga

NEW DATA ABOUT MOSSES ON THE SVALBARD GLACIERS Olga Belkina Polar-Alpine Botanical Garden-Institute, Kola Science Center of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Apatity, Murmansk Province, Russia; e-mail: [email protected] Rapid melting and retreat of glaciers in the Arctic is a cause of sustainable long‐ In Svalbard moss populations were found on 9 glaciers. In 2012, during re‐examination of the populations a few term existence of ablation zone on them. Sometimes these areas are the habitats In 2007 B.R.Mavlyudov collected one specimen on individuals of Bryum cryophilum Mårtensson and some plants of some mosses partly due to good availability of water and cryoconite Bertilbreen (Paludella squarrosa (Hedw.) Brid.) and of Sanionia uncinata were found among H. polare shoots in substratum. 14 species were found in this unusual habitat on Alaska and Iceland: some specimens on Austre Grønfjordbreen (Ceratodon some large cushions. Therefore the next stage of cushion Andreaea rupestris Hedw., Ceratodon purpureus (Hedw.) Brid., Ditrichum purpureus (Hedw.) Brid., Warnstorfia sarmentosa succession had begun –emergence of a di‐ and multi‐species flexicaule (Schwaegr.) Hampe, Pohlia nutans (Hedw.) Lindb., Polytrichum (Wahlenb.) Hedenäs, Sanionia uncinata (Hedw.) community. A similar process was observed earlier on the juniperinum Hedw. (Benninghoff, 1955), Racomitrium fasciculare (Hedw.) Brid. Loeske, Hygrohypnella polare (Lindb.) Ignatov & bone of a mammal that was lying on the same glacier. (=Codriophorus fascicularis (Hedw.) Bendarek‐Ochyra et Ochyra) (Shacklette, Ignatova.). Ceratodon purpureus settled in center of almost spherical 1966), Drepanocladus berggrenii (C.Jens.) Broth. (Heusser, 1972), Racomitrium In 2009 populations of two latter species were studied cushion of Sanionia uncinata on the both butt‐ends of the crispulum var. -

Kenai National Wildlife Refuge Species List, Version 2018-07-24

Kenai National Wildlife Refuge Species List, version 2018-07-24 Kenai National Wildlife Refuge biology staff July 24, 2018 2 Cover image: map of 16,213 georeferenced occurrence records included in the checklist. Contents Contents 3 Introduction 5 Purpose............................................................ 5 About the list......................................................... 5 Acknowledgments....................................................... 5 Native species 7 Vertebrates .......................................................... 7 Invertebrates ......................................................... 55 Vascular Plants........................................................ 91 Bryophytes ..........................................................164 Other Plants .........................................................171 Chromista...........................................................171 Fungi .............................................................173 Protozoans ..........................................................186 Non-native species 187 Vertebrates ..........................................................187 Invertebrates .........................................................187 Vascular Plants........................................................190 Extirpated species 207 Vertebrates ..........................................................207 Vascular Plants........................................................207 Change log 211 References 213 Index 215 3 Introduction Purpose to avoid implying -

Total of 10 Pages Only May Be Xeroxed

CENTRE FOR NEWFOUNDLAND STUDIES TOTAL OF 10 PAGES ONLY MAY BE XEROXED (Without Author's Permission) ,, l • ...J ..... The Disjunct Bryophyte Element of the Gulf of St. Lawrence Region: Glacial and Postglacial Dispersal and Migrational Histories By @Rene J. Belland B.Sc., M.Sc. A thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Biology Memorial University of Newfoundland December, 1Q84 St. John's Newfoundland Abstract The Gulf St. Lawrence region has a bryophyte flora of 698 species. Of these 267 (38%) are disjunct to this region from western North America, eastern Asia, or Europe. The Gulf of St. Lawrence and eastern North American distributions of the disjuncts were analysed and their possible migrational and dispersal histories during and after the Last Glaciation (Wisconsin) examined. Based on eastern North American distribution patterns, the disjuncts fell into 22 sub elements supporting five migrational/ dispersal histories or combinations of these : (1) migration from the south, (2) migration from the north, (3) migration from the west, (4) survival in refugia, and (5) introduction by man. The largest groups of disjuncts had eastern North American distributions supporting either survival of bryophytes in Wisconsin ice-free areas of the Gulf of St. Lawrence or postglacial migration to the Gulf from the south. About 26% of the disjuncts have complex histories and their distributions support two histories. These may have migrated to the Gulf from the west and/or north, or from the west and/or survived glaciation in Gulf ice-free areas. -

Nová Bryologická Literatura X

34 Bryonora, Praha, 28 (2001) Liška J. et Pišút I. (2001): Invázne lišajníky. [Invasive lichens ] - Život, Prostr, Bratislava, 35: 98-99, Liška J, et Wild J. (2000): Závěrečná zpráva ze sledování lišejníků v České republice v období od května 1999 do dubna 2000, - 20 p., Tereza, Praha, Mayrhoher H., Lisická E, et Lackovičová A. (2001): New and interesting records of lichenized fiingi from Slovakia. - Biologia, Bratislava, 56: 355-361. McCarthy P.M., G. Kantvillas et Vězda A, (2001): Foliicolous lichens in Tasmania - Australasian Lichenol. 48: 16-26. Mucina L. et al. [incl. Pišút I ] (2000): Epiphytic lichen and moss vegetation along an altitude gradient on Mount Aenos (Kefalinia, Greece). - Biologia, Bratislava, 55: 43-48. Orthová V. et Kaňka R. (2001): Cladonia portentosa (lichenizované askomycéty) opáť nájdená na Slovensku. [Cladonia portentosa (lichenized Ascomycotina) recollected in Slovakia.] - Bull. Slov. Bot. Spoloč., Bratislava, 23: 29-32. Palice Z. (2001): Nová lichenologická literatura X, - Bryonora, Praha, 27: 23-28. Pišút I. (1999): Nachträge zur Kenntnis der Flechten der Slowakei 13. - Acta Rer. Natur. Mus. Nat. Slov., Bratislava, 45: 3-6. Pišút I. (2000): Nachträge zur Kenntnis der Flechten der Slowakei 14. - Acta Rer. Natur. Mus. Nat. Slov., Bratislava, 46: 11-14. Pišút I. (2000): Dobrá správa pre Bratislavu: Lišajníky sa vracajú! - Chrán. Územia Slov., Bratislava, 44: 3-5, Pišút I. (2001): RNDr. Ing. Antonín Vězda, CSc., octogenarian. - Biologia, Bratislava, 56: 458-460. Pišút I. et Kubinská A. (2000): Lišajníky a machorasty Prírodnej pamiatky Jajkovská suť. - Chrán. Üzemia Slov., Bratislava, 46: 35-36. Počubajová A., Guttová A. et Orthová V. (2000): Kaktuálnemu stavu lichenoflóry NP Slovenský raj. -

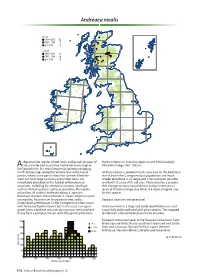

Andreaea Nivalis

Andreaea nivalis Britain 1990–2013 12 1950–1989 7 pre-1950 4 Ireland 1990–2013 0 1950–1989 0 pre-1950 0 characteristic species of wet rocks and gravels in areas of Nardia compressa, Scapania uliginosa and Pohlia ludwigii. Alate snow-lie and associated meltwater burns high in Altitudinal range: 880–1340 m. the Scottish hills. It is most frequently found on dripping, north-facing crags along the ‘cornice line’ at the top of Andreaea nivalis is abundant in its core area on the Ben Nevis corries, where snow persists into the summer. Here the massif and in the Cairngorms but populations are much moss can form large cushions and on Ben Nevis it is smaller elsewhere in its range and it has not been possible remarkably abundant in this habitat with numerous to refind it at some of its old sites. There must be a concern associates, including Deschampsia cespitosa, Saxifraga that changes in snow accumulation and persistence as a stellaris, Anthelia julacea, Lophozia opacifolia, Marsupella result of climate change may affect the more marginal sites sphacelata, M. stableri, Andreaea alpina, A. rupestris, for this species. Ditrichum zonatum, Kiaeria falcata, K. starkei, Polytrichastrum sexangulare, Racomitrium lanuginosum and, rarely, Dioicous; capsules are occasional. Oedipodium griffithianum. In the Cairngorms it often occurs with Andreaea frigida in burns but it also occurs on open Andreaea nivalis is a large and easily identifiable moss and gravel areas which are very wet during snow melt and here is not likely to be confused with other species. The mapped it may form a complex mosaic with Marsupella sphacelata, distribution is therefore believed to be accurate. -

THE ANDEAN SPECIES of PILEA by Ellsworth P. Killip INTRODUCTION

THE ANDEAN SPECIES OF PILEA By Ellsworth P. Killip INTRODUCTION Pilea is by far the largest genus of Urticaceae. Weddell in his final monograph 1 of the family recognized 159 species as valid, about 50 of which were said to occur in the Andes of South America. That these species had a very limited range of distribution was indicated by the fact that more than 30 were known from only a single collection and that only 9 of the others were in any sense widely distributed in the Andean countries. Two, P. microphyUa and P. pubescens, occurred throughout the American Tropics, and P. kyalina and P. dendrophUa extended eastward in South America. In the 50 years following the publication of this monograph only 10 species were described from the Andean region. Because of the large number of specimens of Pilea collected by expeditions to the Andes sponsored by the Smithsonian Institution, the New York Botanical Garden, the Gray Herbarium and the Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University, the Field Museum of Natural History, and the Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia, which were submitted to me for identification but which could not be assigned to any known species, I began the preparation of a mono- graph of all the Andean species. This was completed in 1935 but unfortunately could not be printed in its entirety at that time. Instead, a greatly abridged paper was published,2 which contained a key to all the Andean species, descriptions of 30 new ones, and a few changes of name and of rank. In this there was no opportunity to present descriptions of the earlier species or to discuss their synonymy. -

Chapter 12 Productivity

Glime, J. M. 2017. Productivity. Chapt. 12. In: Glime, J. M. Bryophyte Ecology. Volume 1. Physiological Ecology. Ebook 12-1-1 sponsored by Michigan Technological University and the International Association of Bryologists. Last updated 18 July 2020 and available at <http://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/bryophyte-ecology/>. CHAPTER 12 PRODUCTIVITY TABLE OF CONTENTS Productivity .......................................................................................................................................................... 12-2 Ecological Factors ................................................................................................................................................ 12-2 Ability to Invade ........................................................................................................................................... 12-2 Niche Differences ......................................................................................................................................... 12-3 Growth ................................................................................................................................................................. 12-3 Growth Measurements .................................................................................................................................. 12-4 Annual Length Increase ................................................................................................................................ 12-8 Uncoupling ................................................................................................................................................... -

Kenai National Wildlife Refuge Species List - Kenai - U.S

Kenai National Wildlife Refuge Species List - Kenai - U.S. Fish and Wild... http://www.fws.gov/refuge/Kenai/wildlife_and_habitat/species_list.html Kenai National Wildlife Refuge | Alaska Kenai National Wildlife Refuge Species List Below is a checklist of the species recorded on the Kenai National Wildlife Refuge. The list of 1865 species includes 34 mammals, 154 birds, one amphibian, 20 fish, 611 arthropods, 7 molluscs, 11 other animals, 493 vascular plants, 180 bryophytes, 29 fungi, and 325 lichens. Of the total number of species, 1771 are native, 89 are non-native, and five include both native and non-native subspecies. Non-native species are indicated by dagger symbols (†) and species having both native and non-native subspecies are indicated by double dagger symbols (‡). Fifteen species no longer occur on the Refuge, indicated by empty set symbols ( ∅). Data were updated on 15 October 2015. See also the Kenai National Wildlife Refuge checklist on iNaturalist.org ( https://www.inaturalist.org/check_lists/188476-Kenai-National-Wildlife- Refuge-Check-List ). Mammals ( #1 ) Birds ( #2 ) Amphibians ( #3 ) Fish ( #4 ) Arthropods ( #5 ) Molluscs ( #6 ) Other Animals ( #7 ) Vascular Plants ( #8 ) Other Plants ( #9 ) Fungi ( #10 ) Lichens ( #11 ) Change Log ( #changelog ) Mammals () Phylum Chordata Class Mammalia Order Artiodactyla Family Bovidae 1. Oreamnos americanus (Blainville, 1816) (Mountain goat) 2. Ovis dalli Nelson, 1884 (Dall's sheep) Family Cervidae 3. Alces alces (Linnaeus, 1758) (Moose) 4. Rangifer tarandus (Linnaeus, 1758) (Caribou) Order Carnivora Family Canidae 5. Canis latrans Say, 1823 (Coyote) 6. Canis lupus Linnaeus, 1758 (Gray wolf) 7. Vulpes vulpes (Linnaeus, 1758) (Red fox) Family Felidae 8. Lynx lynx (Linnaeus, 1758) (Lynx) 9. -

The Potential Ecological Impact of Ash Dieback in the UK

JNCC Report No. 483 The potential ecological impact of ash dieback in the UK Mitchell, R.J., Bailey, S., Beaton, J.K., Bellamy, P.E., Brooker, R.W., Broome, A., Chetcuti, J., Eaton, S., Ellis, C.J., Farren, J., Gimona, A., Goldberg, E., Hall, J., Harmer, R., Hester, A.J., Hewison, R.L., Hodgetts, N.G., Hooper, R.J., Howe, L., Iason, G.R., Kerr, G., Littlewood, N.A., Morgan, V., Newey, S., Potts, J.M., Pozsgai, G., Ray, D., Sim, D.A., Stockan, J.A., Taylor, A.F.S. & Woodward, S. January 2014 © JNCC, Peterborough 2014 ISSN 0963 8091 For further information please contact: Joint Nature Conservation Committee Monkstone House City Road Peterborough PE1 1JY www.jncc.defra.gov.uk This report should be cited as: Mitchell, R.J., Bailey, S., Beaton, J.K., Bellamy, P.E., Brooker, R.W., Broome, A., Chetcuti, J., Eaton, S., Ellis, C.J., Farren, J., Gimona, A., Goldberg, E., Hall, J., Harmer, R., Hester, A.J., Hewison, R.L., Hodgetts, N.G., Hooper, R.J., Howe, L., Iason, G.R., Kerr, G., Littlewood, N.A., Morgan, V., Newey, S., Potts, J.M., Pozsgai, G., Ray, D., Sim, D.A., Stockan, J.A., Taylor, A.F.S. & Woodward, S. 2014. The potential ecological impact of ash dieback in the UK. JNCC Report No. 483 Acknowledgements: We thank Keith Kirby for his valuable comments on vegetation change associated with ash dieback. For assistance, advice and comments on the invertebrate species involved in this review we would like to thank Richard Askew, John Badmin, Tristan Bantock, Joseph Botting, Sally Lucker, Chris Malumphy, Bernard Nau, Colin Plant, Mark Shaw, Alan Stewart and Alan Stubbs. -

Entomology of the Aucklands and Other Islands South of New Zealand: Introduction1

Pacific Insects Monograph 27: 1-45 10 November 1971 ENTOMOLOGY OF THE AUCKLANDS AND OTHER ISLANDS SOUTH OF NEW ZEALAND: INTRODUCTION1 By J. L. Gressitt2 and K. A. J. Wise3 Abstract: The Aucklands, Bounty, Snares and Antipodes are Southern Cold Temperate (or Low Subantarctic) islands south of New Zealand and north of Campbell I and Macquarie I. The Auckland group is the largest of all these islands south of New Zealand, and has by far the largest fauna. The Snares, Bounty and Antipodes, though farther north, are quite small islands with limited fauna. These islands have vegetation dominated by tussock grass, bogs with sedges and cryptogams, and shrubs at lower altitudes and in some cases forests of Metrosideros or Olearia near the shores, usually in more protected environments. Bounty Is have almost no vegetation. These islands are breeding places for many sea birds and for hair seals and fur seals. The insect fauna of the Aucklands numbers several hundred species representing most major orders of insects and other land arthropods. This is the introductory article to the first volume treating the land arthropod fauna of the Auckland, Snares, Bounty and Antipodes Islands. The Auckland Islands (SOHO' S; 166° E) form the largest island group south of New Zealand and Australia. Among other southern cold temperate and subantarctic islands they are only exceeded in area by the Falkland Is, South Georgia, Kerguelen and Tierra del Fuego. In altitude they are lower than South Georgia, Tierra del Fuego, Tristan da Cunha, Gough, Marion, Kerguelen, Crozets and Heard, and very slightly lower than the Falklands. -

FOREST FLORA Woodland Conservation News • Spring 2018

Wood Wise FOREST FLORA Woodland Conservation News • Spring 2018 QUESTIONING SURVEYING TIME FOR WOODLAND ANCIENT & RESTORING A BUNCE FLORA WOODLAND WOODLAND WOODLAND FOLKLORE INDICATORS FLORA RESURVEY & REMEDIES CONTENTS Smith / Georgina WTML 3 4 8 11 16 20 22 24 Introduction Spring is probably the best time to appreciate woodland The Woodland Trust’s Alastair Hotchkiss focuses on the ground flora. The warming temperatures encourage restoration of plantations on ancient woodland sites. 25 shoots to burst from bulbs, breaking through the soil Gradual thinning and natural regeneration of native trees Introduction to reach the sunlight not yet blocked out by leaves that can allow sunlight to reach the soil again and enable the 3 will soon fill the tree canopy. Their flowers bring colour return of wildflowers surviving in the seed bank. to break the stark winter and inspire hope in many that Questioning ancient woodland indicators The Woodland Survey of Great Britain 1971-2001 4 see them. recorded a change and loss in broadleaf woodland The species of flora covered in this issue are vascular ground flora species. The driver was thought to be a plants found on the woodland floor layer. Vascular plants 8 Trouble for bluebells? reduction in the use and management of woods. This have specialised tissues within their form that carry finding encouraged an increase in management. Several The world beneath your feet water and nutrients around their stems, leaves and other experts involved look at this and the potential for a future 11 structures, which allow them to grow taller than non- resurvey to analyse the current situation.