Risk Assessment, Risk Management and Risk-Based Monitoring Following a Reported Accidental Release of Poliovirus in Belgium, September to November 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

De Tragikomedie Van De Fietsvoetveer Kwestie

VOORWOORD, Beste inwoners van Hulst, Ik weet niet hoe het u vergaat bij het lezen van dit stuk. Maar bij ons ontstond er in toenemende mate bewondering voor de opsteller, Ir. A.F.M. Broekmans. Niet alleen kenmerkt de heer Broekmans zich als een voorvechter voor wat hij recht vindt, maar hij doet dat ook met een volharding die zich alleen maar laat bewonderen. Een echte doorbijter. Iemand die zich niet opzij laat zetten door overheidsinstanties. Maar het belang van de gewone man en vrouw, zonder daar zelf ook maar iets wijzer van te worden, probeert te verdedigen. Eigenlijk in persoon het prototype van wat wij als SP Hulst ook proberen te zijn. Opkomen voor de belangen van hen die door de overheid in de steek zijn gelaten. We vinden het dan ook bijzonder fijn, dat wij als SP Hulst een bijdrage kunnen leveren om dit kritische relaas over het handelen van de overheid rondom het vraagstuk van de veerverbinding tussen Perkpolder en Kruiningen, het relaas van de heer Broekmans, in brochurevorm uit te geven. Opdat u als lezer net zoals wij als SP Hulst gedaan hebben, kennis kunt nemen van het handelen van overheden die de toets van de gegronde kritiek van de heer Broekmans, niet kunnen doorstaan. De SP Hulst zal zich, zij aan zij met de heer Broekmans, blijven inzetten voor de realisering van het fietsvoetveer Perkpolder/Kruiningen, opdat u als inwoner van Hulst er uw voordeel mee kunt doen. G. van Unen, Voorzitter SP Hulst 2 INHOUD. 1. Inleiding. 2. Geschiedenis veerverbindingen Oostelijk deel Westerschelde. 3. -

Estimating Railway Ridership

28-04-2016 Estimating Railway Ridership DEMAND FOR NEW RAILWAY STATIONS IN THE NETHERLANDS TSJIBBE HARTHOLT S1496352 COMMITTEE: K. GEURS (Chairman) University of Twente L. LA PAIX PUELLO University of Twente T. BRANDS Goudappel Coffeng 0 1 I. SUMMARY Demand estimation for new railway stations is an essential step in determining the feasibility of a new proposed railway stations. Multiple demand estimation models already exist. However these are not always accurate or freely available for use. Therefore a new demand estimation model was developed which is able to provide rail ridership estimations. Main question of this thesis that will be answered is: How can the daily number of passengers of a new train station be forecasted on the basis of departure station choice and network accessibility? Aim is to estimate a demand estimation model which is valid for the whole of the Netherlands and focusses on proposed sprinter train stations. Factors determining total rail ridership Rail ridership can be determined by three main factors: Built environment factors Socio-economic factors Network dependent factors Built environment factors are factors that describe the situation in the direct environment of the station. A subdivision can be made into station environment factors based on the three d’s as described by Cervero and Knockel-man (1997): o Density: Describing the amount of activities in the proximity of the station. This could be the e.g. number of jobs, number of students, shops or total population. o Diversity: describing the diversity of the activities that take place in the proximity of the station. o Design: variables describing the properties of a station (area) as a direct consequence of its design. -

Notification Under Nuclear Energy Act

Notification under Nuclear Energy Act Announcement of environmental impact assessment for construction by ERH of a new nuclear power station at Borssele This announcement is being made by the Minister of Housing, Spatial Planning and the Environment in conjunction with the Minister of Economic Affairs, the Minister of Social Affairs and Employment, the Minister of Transport, Public Works and Water Management and the Minister of Agriculture, Nature and Food Quality (hereafter collectively called 'the Competent Authority'). On 7 September 2010 a notice was received from Energy Resources Holding B.V. (hereafter called ERH) for an environmental impact assessment in connection with its intention to: Build and operate a new nuclear power station at Borssele The intention concerns a nuclear power station with a maximum capacity of 2500 Mwe. ERH wants to build a nuclear power station in order to: • generate a substantial quantity of electricity without appreciable emissions of the greenhouse gas CO2 and other pollutants, such as NOx, SO2 and particulate matter; • produce energy at low variable costs; • contribute to the security of electricity supplies in the Netherlands and Northern Europe by using reliable technology and fuel diversification. These activities require licences under legislation including Section 15, (a) and (b), Section 29 and Section 34 of the Nuclear Energy Act. Other decisions must be taken under legislation including the Water Act and nature conservation laws. An Environmental Impact Report must be drawn up to facilitate decision-making. Important! The intention announced by ERH is unrelated to the intention of DELTA announced in June 2009 to build a nuclear power station at Borssele. -

Long-Term Neighborhood Effects on Integration of Immigrants: the Case of the 1951 Moluccan Boatlift

Long-term neighborhood effects on integration of immigrants: The case of the 1951 Moluccan boatlift Merve Nezihe Özera* Bas ter Weelb Karen van der Wielc** January 31, 2017 Abstract Integration of immigrants to their host countries has been much studied. However, evidence on how physical characteristics of the neighborhoods they live affect their integration is limited and ambiguous. This paper aims to estimate the impact of the physical neighborhood characteristics on immigrants’ long term education and labor market outcomes. We use administrative data on Moluccan immigrants in the Netherlands to exploit the random variation in their settlements after they had been boatlifted from Indonesia in 1951. Moluccan immigrants were assigned to residential areas called ‘woonoorden’, which differed in terms of their distance to the local native community, educational infrastructure, employment opportunities nearby, and housing structure. We analyze education and labor market outcomes of children born in these settlements after 45 to 60 years. We find that physical characteristics matter for these second generation immigrants but impacts differ between girls and boys. A kilometer increase in the distance to the local community results in 0.7% less likelihood of women having at least an upper secondary school degree. For men, the education level is not affected. Instead, we find that a kilometer increase in the distance to the local community decreases men’s income by 1.2% while having no significant effect on women’s. Our findings are instructive on the potential impacts of the location of refugee camps on further integration of refugees to host countries. Key words: immigrant, neighborhood effects, integration, Moluccan, refugee JEL classification: J15, J24, R23 a Research Centre for Education and the Labour Market (ROA), Maastricht University, The Netherlands b SEO Amsterdam Economics and University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands c CPB Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis, The Netherlands * Corresponding author at: ROA, Maastricht University, P.O. -

Everything You Should Know About Zeeland Provincie Zeeland 2

Provincie Zeeland History Geography Population Government Nature and landscape Everything you should know about Zeeland Economy Zeeland Industry and services Agriculture and the countryside Fishing Recreation and tourism Connections Public transport Shipping Water Education and cultural activities Town and country planning Housing Health care Environment Provincie Everything you should know about Zeeland Provincie Zeeland 2 Contents History 3 Geography 6 Population 8 Government 10 Nature and landscape 12 Economy 14 Industry and services 16 Agriculture and the countryside 18 Fishing 20 Recreation and tourism 22 Connections 24 Public transport 26 Shipping 28 Water 30 Education and cultural activities 34 Town and country planning 37 Housing 40 Health care 42 Environment 44 Publications 47 3 History The history of man in Zeeland goes back about 150,000 brought in from potteries in the Rhine area (around present-day years. A Stone Age axe found on the beach at Cadzand in Cologne) and Lotharingen (on the border of France and Zeeuwsch-Vlaanderen is proof of this. The land there lies for Germany). the most part somewhat higher than the rest of Zeeland. Many Roman artefacts have been found in Aardenburg in A long, sandy ridge runs from east to west. Many finds have Zeeuwsch-Vlaanderen. The Romans came to the Netherlands been made on that sandy ridge. So, you see, people have about the beginning of the 1st century AD and left about a been coming to Zeeland from very, very early times. At Nieuw- hundred years later. At that time, Domburg on Walcheren was Namen, in Oost- Zeeuwsch-Vlaanderen, Stone Age arrowheads an important town. -

Referenties C4I 2020.Pdf

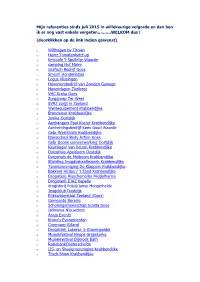

Mijn referenties sinds juli 2015 in willekeurige volgorde en dan ben ik er nog vast enkele vergeten……….WELKOM dus ! (doorklikken op de link indien gewenst) o Wilthagen bv Tholen o Heinz Tomatenketchup o fietscafé 't Spulletje Waarde o camping Hof Maire o Grafisch Bedrijf Goes o Smoofl Hondenijsjes o Logus Vlissingen o Hoveniersbedrijf van Zweden Gawege o Havendagen Zierikzee o VHC Kreko Goes o Zorggroep Ter Weel o SVRZ zorgt in Zeeland o Westequipement Krabbendijke o Brandweer Krabbendijke o Jonika Oostdijk o Aanhangers Paul Koster Krabbendijke o Aannemingsbedrijf Kees Goud Waarde o Gebr Weststrate Krabbendijke o Dansschool Body Action Goes o Gebr Boone uienverwerking Oostdijk o Keurslager van Velzen Krabbendijke o Dorpshuis Apeldoorn Oostdijk o Dorpshuis de Meiboom Krabbendijke o Stichting Jeugdvakantieweek Krabbendijke o Tennisvereniging De Klappers Krabbendijke o Bakkerij Hirdes / ‘t Zand Krabbendijke o Drogisterij Hisschemöller Middelharnis o Drogisterij DIAZ Kapelle o drogisterij Poleij-Janse Hoogerheide o Jeugdclub Oostdijk o Rijkswaterstaat Zeeland (Goes) o Gemeente Borsele o Scholengemeenschap Scalda Goes o Istimewa Nieuwdorp o Ansja Events o Kroko's Evenementen o Coremans Rilland o Drogisterij Lokerse 's-Gravenpolder o Muziekfestival Hrieps Grijpskerke o Muziekfestival Dijkrock Bath o RabobankOosterschelde o IJS- en Skeelervereniging Krabbendijke o Truck Show Krabbendijke o Camper Park Zeeland o Beveland Wonen o TSG - 's-Gravenpolder o Emergis - Goes o Neels Krabbendijke o Ter Weel Actief o Dockwize Vlissingen o Fletcher hotel -

Waterschap Scheldestromen

CENTRAAL STEMBUREAU Kandidatenlijsten verkiezing van de leden van het algemeen bestuur van het waterschap Scheldestromen De voorzitter van het centraal stembureau voor de verkiezing van de leden van het algemeen bestuur van het waterschap Scheldestromen; gelet op artikel I 17 van de Kieswet; maakt bekend dat voor de op 18 maart 2015 te houden verkiezing de volgende geldige kandidatenlijsten zijn ingeleverd: Lijst 1 Waterschapspartij Zeeuws-Vlaanderen Gecombineerd met Algemene Waterschapspartij Zeeland Nr Naam Woonplaats 1 de Feijter - de Feijter, M.P.E. (Rian) (v) Axel 2 Verdurmen, J.J.M. (Jos) (m) Zaamslag 3 Dobbelaer, A.T.M. (Fons) (m) Sint Jansteen 4 Pielaet - Leenhouts, S.A. (Suzan) (v) Aardenburg 5 de Feijter - Dekker, M.T. (Magda) (v) Zaamslag 6 de Bruijckere, G.A.M. (Geert) (m) Breskens 7 van den Kieboom, M.C. (Rene) (m) Kloosterzande 8 Snoodijk, P.A.A. (Peter) (m) Axel 9 Rosendaal - Dees, J.M.C. (Jenny) (v) Zuidzande 10 van Boom, G. (Giel) (m) Hoek 11 Hemelsoet - de Jaeger, M.I.R. (Marijke) (v) Westdorpe 12 de Kock, E.P.A.E. (Edwin) (m) Kloosterzande 13 Stoffels, A.L. (Bram) (m) Terneuzen 14 Basting, A.C. (Bram) (m) Retranchement 15 Baert, G.L.A.M. (Guus) (m) Koewacht 16 van Hoeve, S. (Simon) (m) Axel 17 den Dekker, M.W.F.M. (Rien) (m) Kloosterzande 18 de Bruijn, A. (Anton) (m) Terneuzen 19 Poissonnier - Dekker, M.J. (Marianne) (v) Waterlandkerkje 20 van Schaik, J.M. (Co) (m) Axel 21 van den Berg, G. (Gijs) (m) Terneuzen 22 Duerinck, A.P. (Fons) (m) Vogelwaarde 23 Aardewerk, P. -

Kruiningen, Index Ref. Trouwen 1671-1810

Kruiningen, ref. trouwen 1671-1810 Bron Zeeuws archief, toegang 164, inv. nr. GA-24 en toegang 995, inv. nr. KRU-4 GA-24 bewerking van het trouwboek der Hervormde gemeente 1671- 1748. Origineel niet aanwezig op het R.A.te Middelburg en niet genoemd in "Retroacta van den Burgerlijken Stand in Zeeland" van A. Mulder. Extract van J. Hoekman te Amsterdam, 1952. Tekst tussen haken is van Hoekman/ Mulder https://proxy.archieven.nl/0/52DE5DF3335842FD93BBE3B708210BE5 Afbeeldingen: https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-9P67- 9W5P?cat=101114 [REGISTRATIE] KRU-4 omvat de periode 1748 (22 januari)-1810 (9 december). Tekst tussen vierkante haken is van John Goossen https://proxy.archieven.nl/0/A517C39B632E4C62A0588DF7D9A6459D Afbeeldingen: https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QSQ- G9QJ-B7H4?i=15&cc=2036997 [REGISTRATIE] Bewerking John Goossen Aangeboden ter plaatsing Geneascript 22 november 2019, informatiepagina - https://geneaknowhow.net/script/index.html Het kopiëren (downloaden) van dit bestand is toegestaan voor persoonlijk gebruik en voor verspreiding op niet-commerciële basis. Commerciële verspreiding is uitdrukkelijk niet toegestaan. Bij gebruikmaking van gegevens uit deze bewerking ten behoeve van publicaties, in welke vorm ook, moet een adequate bronvermelding naar deze bewerking worden aangegeven. Deze publicatie is een bewerking van Trouwboek Kruiningen 1671-1748 (kopie) aangevuld met een transcriptie vanhet Trouwboek Kruiningen 1748-1810. Tekst tussen haken tot 1748 is van Hoekman/ Mulder, tekst tussen vierkante haken is van ondergetekende. Ik geef als maker van deze bewerking de Stichting Geneaknowhow toestemming om dit bestand te publiceren op haar domein. John Goossen. * * * Trouwboek der Hervormde Gemeente te KRUININGEN 1671–1748. -

Connexxion in Reimerswaal Verzamelde Klachten Van Inwoners

Connexxion in Reimerswaal Verzamelde klachten van inwoners PvdA Reimerswaal Kruiningen, 1 februari 2009 Reimerswaal Inhoud Hoofdstuk 1. Inleiding 4 1.1 Hoe was het ook al weer…. 4 1.2 Augustus 2008: lijn 28 4 1.3 November 2008: lijn 27 4 1.4 December 2008: invoer nieuwe dienstregeling 4 Hoofdstuk 2. Hansweert 5 2.1 Lijn 28 (Hansweert – Goes vv) 5 2.2 Lijn 29 (Hansweert – Yerseke) 5 2.3 Lijn 39 (Rilland – Goes vv) 5 2.4 Lijn 30 (Wemeldinge – Hansweert vv) 6 2.5 Ondertussen… een oplossing ?? 6 2.6 Aansluiting op ander openbaar vervoer 7 2.7 De ontvangen mailtjes: 7 Hoofdstuk 3. Kruiningen 10 3.1 Lijn 29 (Yerseke – Hansweert vv) 10 3.2 Lijn 39 (Rilland – Goes) 10 3.3 Lijn 46 / 47 (Middelburg – Krabbendijke) 11 3.4 Aansluiting op ander openbaar vervoer 11 3.5 De ontvangen mailtjes: 11 Hoofdstuk 4. Waarde 12 4.1 Lijn 194 (buurtbus Waarde) 12 4.2 De ontvangen mailtjes: 13 Hoofdstuk 5. Krabbendijke 13 5.1 Lijn 39 (Rilland – Goes) 13 5.2 De ontvangen mailtjes: 13 Hoofdstuk 6. Rilland 13 6.1 Lijn 39 (Rilland – Goes) 13 Hoofdstuk 7. Yerseke 13 7.1 Lijn 27 (Yerseke – Goes) 13 7.2 Lijn 29 (Yerseke – Hansweert) 14 7.3 Voorzieningen NS Kruiningen-Yerseke 14 7.4 De ontvangen mailtjes: 14 Hoofdstuk 8. Samenvatting 15 Hoofdstuk 9. En verder…. 16 Hoofdstuk Bijlage: dienstregelingen lijn 27, 28, 29, 39 en 194 17 1. Inleiding 1.1 Hoe was het ook al weer…. Het openbaar vervoer in Reimerswaal was, op een paar schoonheidsfoutjes na, redelijk goed geregeld. -

Logistics Planning of a Flexible Evacuation Strategy for the Healthcare Community Residing in Reimerswaal

LOGISTICS PLANNING OF A FLEXIBLE EVACUATION STRATEGY FOR THE HEALTHCARE COMMUNITY RESIDING IN REIMERSWAAL Final Thesis SEPTEMBER 21, 2018 1 Logistics Planning of a Flexible Evacuation Strategy for the Healthcare Community Residing in Reimerswaal Final Thesis Place of completion of the report: Vlissingen, the Netherlands Date: 21‐9‐2018 Course: CU11113 Final Thesis Study: (B‐IL4HL) Logistics Engineering Student‐number: 0067571 Year of study: 2017/2018 Study Part: Final Thesis Name of supervisors: G.A.M. van der Beemt Version: 2.1 2 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ACO: Adviescommissie voor het Ouderenbeleid CI: Critical infrastructure DPG: Director of Public Healthcare FMECA: Failure mode, effect and criticality analysis GGD: Gemeentelijke gezondheidsdienst GHOR: Geneeskundige Hulpverleningsorganisatie in de Regio GRIP: Gecoördineerde Regionale Incidentbestrijdings Procedure HC1: Healthcare centres inside Reimerswaal HC2: Healthcare centres outside Reimerswaal IBT: Intensief Behandelteam Thuis ICF: International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health KPI: Key Performance Indicator MBT: Metallization‐Based Treatment MRAC: Model Reference Adaptive Control ROT: Regionaal Operationeel Team VLM: Vereniging Logistiek Management VZR: Veiligheidsregio Zeeland Wvr: Wet veiligheidsregio 3 SUMMARY This research has focused on three different aspects of a possible dike breach in the municipality of Reimerswaal. Which were; what can be considered as the healthcare community in the municipality, the evacuation process of such individuals and finally, the effects that the failure of critical infrastructure can have in this process. Human logistics, is the application of logistic theories into the ‘flow of people’. Whilst in an regular supply chain process, the product is whatever is being produced, in an evacuation process the ‘product’ is the people that need to be evacuated. -

Rapport 3855 Kruiningen Slagveldstraat Kaft

Kruiningen, Slagveldstraat rapport 3656 W. Jezeer AD C ArcheoProjecten is een onderdeel van het Archeologisch Diensten Centru m Kruiningen Slagveldstraat (gemeente Reimerswaal) Een Inventariserend Veldonderzoek in de vorm van proefsleuven W. Jezeer Colofon ADC Rapport 3656 Kruiningen Slagveldstraat (gemeente Reimerswaal) Een Inventariserend Veldonderzoek in de vorm van proefsleuven W. Jezeer In opdracht van: Gemeente Reimerswaal Foto’s en tekeningen: ADC ArcheoProjecten, tenzij anders vermeld © ADC ArcheoProjecten, Amersfoort, juni 2014 Niets uit deze uitgave mag worden vermenigvuldigd en/of openbaar gemaakt worden door middel van druk, fotokopie of op welke wijze dan ook zonder voorafgaande schriftelijke toestemming van de uitgevers. ADC ArcheoProjecten aanvaardt geen aansprakelijkheid voor eventuele schade voortvloeiend uit de toepassing van de adviezen of het gebruik van de resultaten van dit onderzoek. J. Dijkstra ISSN 1875-1067 ADC ArcheoProjecten Tel 033 299 8181 Postbus 1513 3800 BM Amersfoort Fax 033 299 8180 Email [email protected] Inhoudsopgave Administratieve gegevens van het onderzoeksgebied 4 Samenvatting 5 1 Inleiding 7 Opzet van het rapport 7 2 Vooronderzoek 9 2.1 Geologie 9 2.2 Geomorfologie en AHN 11 2.3 Bodem en grondwater 12 2.4 Historische situatie en mogelijke verstoringen 12 2.5 Bewoningsgeschiedenis Zuid-Beveland 13 2.6 Ontwikkelingen Kruiningen 15 2.7 Historische kaarten 17 2.8 Bekende waarden 21 2.9 Verwachting 23 3 Doel van het onderzoek en onderzoeksvragen 24 4 Methoden 25 5 Resultaten 28 5.1 Fysisch geografisch onderzoek 28 5.2 Sporen en structuren 29 5.3 Vondstmateriaal 42 5.3.1 Aardewerk 42 5.3.2 Natuursteen (M. Melkert, MarianMelkert) 43 5.3.3 Dierlijk bot (J. -

Groundwater in the New Intertidal Area Perkpolder

Groundwater in the new intertidal area Perkpolder Monitoring groundwater and soil of the new intertidal area Perkpolder Author: J.J.E. Schouwenaars Date: 02-06-2016 Version: 1.2 City: Vlissingen Institution: HZ University of Applied Sciences & Royal NIOZ Research group: Building with Nature Institution: HZ University of Applied Sciences Program: Bachelor Water Management Supervisor: J.A.M. van der Welle Groundwater in the new intertidal area Perkpolder Monitoring groundwater and soil of the new intertidal area Perkpolder Cover photo: Perkpolder (Bron: http://www.viadrupsteen.nl/perkpolder/#/loc03/20 tot 30 jaar) Author J.J.E. Schouwenaars Date: 02-06-2016 Version: 1.2 City: Vlissingen Institution: HZ University of Applied Sciences Department: Delta Academy Program: Aquatische Ecotechnologie Supervisor: J.A.M. van der Welle Course: Final Thesis Educational year: 2015 - 2016 Semester: 8 Summary Intertidal areas in the Netherlands suffer from divers pressures in the delta. The Western Scheldt has an open connection to the sea. This system is in use for the Port of Antwerp, for which dredging is required. Therefore, Rijkswaterstaat has to compensate natural areas, among which intertidal areas. Area development Plan Perkpolder is one of these projects. In addition to the marina, houses and golf course, a 75 hectare intertidal area is created. Of these 75 ha, 40 ha is a compensation for the second dredging of the Western Scheldt. The remaining 35 ha is for the “Natuurpakket Westerschelde”, a project for the development of 600 ha of intertidal flats and salt marshes. This research focusses on describing the current situation of the groundwater and soil chemistry of the intertidal area at Perkpolder.