Terry Jones and Global Free Speech in the Internet Age

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

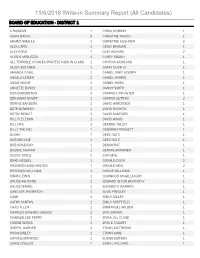

11/6/2018 Write-In Summary Report (All Candidates) BOARD of EDUCATION - DISTRICT 1

11/6/2018 Write-in Summary Report (All Candidates) BOARD OF EDUCATION - DISTRICT 1 A RAINEAR 1 CHRIS MURRAY 1 ADAM HATCH 2 CHRISTINE ASHOO 1 AHMED SMALLS 1 CHRISTINE KUSHNER 2 ALEX CARR 1 CINDY BEAMAN 1 ALEX FORD 1 CLAY WILKINS 2 ALICE E VERLEZZA 1 COREY BRUSH 1 ALL TERRIBLE CHOICES PROTECT KIDS IN CLASS 1 CYNTHIA WOOLARD 1 ALLEN BUTCHER 1 DAFFY DUCK III 1 AMANDA GOWL 1 DANIEL GREY SCURRY 1 ANGELA LEISER 2 DANIEL HARRIS 1 ANGIE WIGHT 1 DANIEL HORN 1 ANNETTE BUSBY 1 DANNY SMITH 1 BEN DOBERSTEIN 2 DAPHNE LANCASTER 1 BENJAMIN DOVER 1 DAPHNE SUTTON 2 BERNIE SANDERS 1 DAVID HARDISTER 1 BETH BOWMAN 1 DAVID RUNYON 1 BETSY BENOIT 1 DAVID SANFORD 1 BILL FLELEHAN 1 DAVID WOOD 1 BILL NYE 1 DEANNE TALLEY 1 BILLY THE KID 1 DEBORAH PRICKETT 1 BLANK 7 DEEZ NUTS 1 BOB MELONE 1 DEEZ NUTZ 1 BOB SPAZIANO 1 DEMOCRAT 1 BOBBIE CAVNAR 1 DENNIS BRAWNER 1 BOBBY JONES 1 DON MIAL 1 BRAD HESSEL 1 DONALD DUCK 2 BRANDON WASHINGTON 1 DONALD MIAL 2 BRANNON WILLIAMS 1 DONNE WILLIAMS 1 BRIAN LEWIS 1 DURWOOD MCGILLACUDY 1 BRUCE ASHFORD 1 EDWARD ALTON HUNTER IV 1 BRUCE MAMEL 1 ELIZABETH WARREN 1 CANDLER THORNTON 1 ELVIS PRESLEY 1 CASH 1 EMILY JOLLEY 1 CATHY SANTOS 1 EMILY SHEFFIELD 1 CHAD ALLEN 1 EMMANUEL WILDER 1 CHARLES EDWARD CHEESE 1 ERIC BROWN 1 CHARLES LEE PERRY 1 ERIKA JILL CLOSE 1 CHERIE WIGGS 1 ERIN E O'LEARY 1 CHERYL GARNER 1 ETHAN MATTHEWS 1 CHRIS BAILEY 1 ETHAN SIMS 1 CHRIS BJORNSTED 1 EUSHA BURTON 1 CHRIS COLLUM 1 EVAN L POLLARD 1 11/6/2018 Write-in Summary Report (All Candidates) BOARD OF EDUCATION - DISTRICT 1 EVERITT 1 JIMMY ALSTON 1 FELIX KEYES 1 JO ANNE -

Law School Announcements 2013-2014 Law School Announcements Editors [email protected]

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound University of Chicago Law School Announcements Law School Publications Fall 2013 Law School Announcements 2013-2014 Law School Announcements Editors [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/ lawschoolannouncements Recommended Citation Editors, Law School Announcements, "Law School Announcements 2013-2014" (2013). University of Chicago Law School Announcements. Book 2. http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/lawschoolannouncements/2 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Publications at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Chicago Law School Announcements by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago The Law School Announcements Fall 2013 ii The Law School Contents OFFICERS AND FACULTY ........................................................................................................ 1 Officers of Administration ............................................................................................ 1 Officers of Instruction .................................................................................................... 1 Law School Visiting Committee................................................................................... 7 THE LAW SCHOOL .............................................................................................................. -

Sample Ballot

STATE AND FEDERAL GENERAL ELECTION BARTLETT, COLLIERVILLE, GERMANTOWN, MILLINGTON MUNICIPAL ELECTION SHELBY COUNTY, TENNESSEE NOVEMBER 8, 2016 PRESIDENT AND VICE-PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES VOTE FOR ONE (1) Electors For DONALD J. TRUMP For President and MICHAEL R. PENCE For Vice-President Republican Party Nominee Electors For HILLARY CLINTON For President and TIM KAINE For Vice-President Democratic Party Nominee Electors For “ ROCKY” ROQUE DE LA FUENTE For President and MICHAEL STEINBERG For Vice-President Independent Candidate Electors For GARY JOHNSON For President and WILLIAM F. WELD For Vice-President Independent Candidate Electors For ALYSON KENNEDY For President and OSBORNE HART For Vice-President Independent Candidate Electors For MIKE SMITH For President and DANIEL WHITE For Vice-President Independent Candidate Electors For JILL STEIN For President and AJAMU BARAKA For Vice-President Independent Candidate WRITE-IN UNITED STATES CONGRESS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES EACH VOTER VOTES IN ONLY ONE CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT UNITED STATES HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES DISTRICT 8 REPUBLICAN PARTY NOMINEE DAVID KUSTOFF DEMOCRATIC PARTY NOMINEE RICKEY HOBSON INDEPENDENT CANDIDATES SHELIA L. GODWIN JAMES HART ADRIAN M. MONTAGUE MARK J. RAWLES KAREN FREE SPIRIT TALLEY-LANE WRITE-IN UNITED STATES HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES DISTRICT 9 REPUBLICAN PARTY NOMINEE WAYNE ALBERSON DEMOCRATIC PARTY NOMINEE STEVE COHEN INDEPENDENT CANDIDATE PAUL COOK WRITE-IN EACH VOTER VOTES IN ONLY ONE SENATORIAL DISTRICT TENNESSEE SENATE DISTRICT 30 DEMOCRATIC PARTY NOMINEE SARA P. KYLE WRITE-IN TENNESSEE SENATE DISTRICT 32 REPUBLICAN PARTY NOMINEE MARK NORRIS WRITE-IN EACH VOTER VOTES IN ONLY ONE HOUSE DISTRICT TENNESSEE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES DISTRICT 83 REPUBLICAN PARTY NOMINEE MARK WHITE DEMOCRATIC PARTY NOMINEE LAWRENCE A. -

Anti-Islam Firestorm Top: Signs Are Seen Outside the Dove World Outreach Center, Run by Terry Jones

sunday features SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 12, 2010 Gainsville tries to deflect church’s anti-Islam firestorm Top: Signs are seen outside the Dove World Outreach Center, run by Terry Jones. Above: Paula Pope protests against Terry Jones in Gainesville, Florida, on Friday. Many of the city’s residents are pondering how to distance themselves from neighbor Terry Jones PHOTOS: EPA AND AFP BY DAMIEN CAVE NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE, GAINESVILLE, FLORIDA tephanie George used to see members Marine barracks bombing in 1983 that killed the positive side of our message of who we members of the church wore to school last Perfect, she thought. She printed 200 of the Dove World Outreach Center 241 service members in Beirut. are, and then that will set an example for year and that led to standard uniforms this shirts to test demand, asking only for S at her neighborhood grocery store, “It’s frustrating,” said the Reverend others in our society who are maybe on the year. But she refused. donations. As of Friday evening, more than wearing T-shirts that said “Islam is of the Larry Reimer, pastor of the United Church fence,” he said. On Tuesday, after seeing the firestorm 1,000 shirts had flown out the door. devil.” But on Friday, she and her friend of Gainesville. It was just before noon and That seemed to be exactly the goal of Jones created, she decided to act. She said By nightfall on Friday, Revels, looking Lynda Dillon showed up early at Dragonfly he was standing at the door of Dove in Dragonfly. -

Neo-Nazi Named Jeffrey Harbin Was End Birthright Citizenship

SPECIAL ISSUE IntelligencePUBLISHED BY SPRING 2011 | ISSUE 141 THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTERReport THE YEAR IN HATE & EXTREMISM HATE GROUPS TOP 1000 Led by antigovernment ‘Patriot’ groups, the radical right expands dramatically for the second year in a row EDITORIAL The Arizonification of America BY MARK POTOK, EDITOR when even leading conser- As we explain in this issue, this dramatic growth of the rad- vatives worry out loud about the ical right for the second consecutive year is related to anger right-wing vitriol and demoniz- over the changing racial make-up of the country, the ailing ing propaganda so commonplace in economy and the spreading of demonizing propaganda and contemporary America, you’ve got other kinds of hate speech in the political mainstream. to be concerned about where our The white-hot political atmosphere is not limited to hard- country is headed. line nativist politicians, conspiracy-mongering cable news This January, former President hosts, or even openly radical hate groups. During the same George W. Bush, speaking in a month when most of these conservative commentaries were question-and-answer session written, the nation witnessed an extraordinary series of at Texas’ Southern Methodist events that highlighted the atmosphere of political extremism. University, warned that the nation seemed to be reliving its On Jan. 8, a Tucson man opened fire in a parking lot on worst anti-immigrant moments. “My point is, we’ve been U.S. Rep. Gabrielle Giffords, Democrat of Arizona, killing six through this kind of period of isolationism, protectionism, people, critically wounding the congresswoman and badly nativism” before, he said. -

Terry Jones Arrested, Found with Gas-Soaked Qurans According to the Release

UF quarterback Jeff Driskel suffered a knee sprain against Miami but is expected to play against Tennessee. Read the Not officially associated with the University of Florida Published by Campus Communications, Inc. of Gainesville, Florida We Inform. You Decide. story on page 15. VOLUME 108 ISSUE 16 WWW.ALLIGATOR.ORG THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 12, 2013 Terry Jones arrested, found with gas-soaked Qurans according to the release. Deputies also arrested the driver, He was on the way to burn 2,998 near Tampa 44-year-old Dove World Outreach Pas- KATHRYN VARN At about 5 p.m., deputies arrested 61-year-old Jones tor Marvin Wayne Sapp Jr., on charges of Alligator Staff Writer [email protected] about 35 miles east of Tampa on one count of unlawful con- unlawful conveyance of fuel and invalid veyance of fuel, according to a Polk County Sheriff’s Offi ce registration for the smoker attached to MULBERRY, Fla. — Polk County Sheriff’s Offi ce depu- news release. His organization had planned to burn 2,998 his car. ties arrested the Rev. Terry Jones of Dove World Outreach copies of the Quran in a park, according to its website. Deputies seized Sapp’s 1998 Chevrolet Center — which left Gainesville this summer — on Wednes- Jones Jones will additionally face a charge of unlawful open 1500 pickup truck as well as the smoker day afternoon after they found a smoker full of kerosene- carry of a fi rearm because some deputies said they saw him containing the Qurans, according to the release. soaked Qurans attached to the car he was riding in. -

TABLE of CONTENTS Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents Introduction . v A Message from CAIR’s National Executive Director v Key Findings vi Background and Acknowledgments vii CAIR’s Vision Regarding Islamophobia in America ix 01 Financing Prejudice and Hate . 1 Background 1 Methods 2 The Inner Core 3 The Outer Core 3 Network Interdependence 6 Examples of Affluent Supporters of the Network 12 Leadership Compensation 14 Research Limits 14 02 The Inner Core . 17 Act! for America, Brigitte Gabriel 17 American Freedom Defense Initiative (AFDI) and its project Stop the Islamization of America 18 American Freedom Law Center, David Yerushalmi 19 American Public Policy Alliance 20 American Islamic Forum for Democracy (AIFD), Dr. Zuhdi Jasser 20 Americans Against Hate, Joe Kaufman 21 Atlas Shrugs, Pamela Geller 22 Bare Naked Islam 23 Bay People 23 Center for Security Policy (CSP), Frank Gaffney 23 Center for the Study of Political Islam (CSPI), Bill French 24 Christian Action Network 24 Citizens for National Security 24 The Clarion Fund 24 Concerned American Citizens 25 Concerned Citizens for the First Amendment (CCFA) 26 Counter Terrorism Operations Center (CTOC), Sam Kharoba 26 David Horowitz Freedom Center, David Horowitz 26 Debbieschlussel.com, Debbie Schlussel 27 Council on American-Islamic Relations i ISLAMOPHOBIA AND ITS IMPACT IN THE UNITED STATES | LEGISLATING FEAR Dove World Outreach Center, Terry Jones 27 Florida Family Association, David Caton 27 Former Muslims United, Nonie Darwish 28 Forum for Middle East Understanding, Walid Shoebat 29 Gates of Vienna 30 Investigative Project on Terrorism (IPT), Steve Emerson 30 Jihad Watch, Robert Spencer 31 Middle East Forum, Daniel Pipes 32 Middle East Media Research Institute (MEMRI) 33 Militant Islam Monitor 34 SAE Productions 34 Society of Americans for National Existence 34 Stop the Islamization of Nations 35 Strategic Engagement Group, Stephen Coughlin, John Guandolo 35 Tennessee Freedom Coalition, Lou Ann Zelenik 36 The Shoebat Foundation 36 The United West 36 The Virginia Anti-Sharia Taskforce 36 03 Islamophobic Themes . -

The Bible and the Ballot: the Christian Right in American Politics

Augsburg University Idun Theses and Graduate Projects 2011 The iB ble and the Ballot: the Christian Right in American Politics Terence L. Burns Augsburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://idun.augsburg.edu/etd Part of the American Politics Commons, Leadership Studies Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Burns, Terence L., "The iB ble and the Ballot: the Christian Right in American Politics" (2011). Theses and Graduate Projects. 910. https://idun.augsburg.edu/etd/910 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Idun. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Graduate Projects by an authorized administrator of Idun. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ,,4-UGSBURG C-O-L-L-E-G-E MASTER OF ARTS IN LEADERSHIP Terence L. Burns The Bible and the Ballot: The Chris 2011 Augsburg Coliege Linden Library Minneapolis, MN 55454 THE BIBLE AND THE BALLOT: THE CHRISTIAN RIGHT IN AMERICAN POLITICS TERENCE L. BURNS Submitted in partial fiilfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts in Leadership AUGSBURG COLLEGE MINNEAPOLIS, MINNESOTA 2011 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to first thank Augsburg College and also congratulate the College for their wisdom and foresight in the creation of this wonderful program in Leadership. The faculty and staff of the Master of Arts in Leadership program have been extraordinary helpful and competent in their administration of this program. I have truly enjoyed every course. Special thanks to Professor Norma Noonan, whose leadership of the MAL program has been inspiring and creative and should serve as an example for both educators and leaders. -

UNIVERSITY of MASSACHUSETTS ROUNDTABLE SYMPOSIUM LAW JOURNAL

UNIVERSITY of MASSACHUSETTS ROUNDTABLE SYMPOSIUM LAW JOURNAL TRENDS AND ISSUES IN TERRORISM AND THE LAW University of Massachusetts School of Law Dartmouth North Dartmouth, MA CITE AS 5 U. MASS. ROUNDTABLE SYMP. L. J. (2010). ROUNDTABLE SYMPOSIUM LAW JOURNAL Volume 5 2010 EDITORIAL BOARD Editor-In-Chief BRITTANY PINSON Managing Editor MARY BONO Executive Articles Editor NEIL SMOLA Executive Notes Editor KRISTIN O'NEILL Executive Editor ALICIA BROWN Symposium Conference Coordinator ALICIA BROWN EDITORIAL STAFF JOHN CROWLEY, III VICTORIA FRANCO HEIDI GRINSELL PATRICK NOONAN RUSSELL WHYNACHT FACULTY ADVISORS PHILIP E. CLEARY THOMAS J. CLEARY Copyright © 2010 by University of Massachusetts School of Law Dartmouth. The University of Massachusetts Roundtable Symposium Law Journal is published annually by the students of the University of Massachusetts School of Law Dartmouth, North Dartmouth, Massachusetts, 02747. Materials contained herein may be duplicated for educational purposes if: (1) each copy is distributed at or below its duplication cost; (2) the author and the Roundtable Symposium Law Journal are identified; (3) proper notice is affixed to each copy; (4) the Roundtable Symposium Law Journal receives notice of its use. Information for Contributors: The Roundtable Symposium Law Journal invites the submission of unsolicited manuscripts. For information about upcoming topics and symposia, please visit our website at http://www.umassd.edu/law/academics/roundtablesymposium lawjournal/. ROUNDTABLE SYMPOSIUM LAW JOURNAL Volume 5 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS TRENDS AND ISSUES IN TERRORISM AND THE LAW FOREWORD TRENDS AND ISSUES IN TERRORISM AND THE LAW: FOREWORD ................................................................................ Thomas J. Cleary ................................................................ 1 ARTICLES ―THE LONG AND WINDING ROAD‖: REFLECTIONS ON AMERICA‘S WAR(S) ON TERRORISM AND COUNTERTERRORISM EFFORTS POST 9/11 .................................................................. -

Coleman, Marshall University Class of 1968 Graduate, Speaks to a Group of Pre-Law Students in Foundation Hall’S Nate Ruffin Lounge on Friday

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar The aP rthenon University Archives 9-24-2012 The aP rthenon, September 24, 2012 Shane Arrington [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/parthenon Recommended Citation Arrington, Shane, "The aP rthenon, September 24, 2012" (2012). The Parthenon. Paper 60. http://mds.marshall.edu/parthenon/60 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the University Archives at Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The aP rthenon by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. C M Y K 50 INCH MONDAY Thundering Herd pluck Owls September 24, 2012 in OT, 54-51 | More on Sports VOL. 116 NO. 15 | MARSHALL UNIVERSITY’S STUDENT NEWSPAPER | MARSHALLPARTHENON.COM PHOTOS BY SHANE ARRINGTON | THE PARTHENON ALL: Judge Rudy Coleman, Marshall University class of 1968 graduate, speaks to a group of pre-law students in Foundation Hall’s Nate Ruffin Lounge on Friday. Coleman was in town to visit his alma mater and share his experiences with those who plan to pursue law as a career. Coal mine to court room Judge gives Marshall grad overcomes odds to succeed advice to By SHANE ARRINGTON EXECUTIVE EDITOR MU students While Marshall University is a THE PARTHENON home of sorts for many colors, Marshall University stu- creeds and cultures, it does not dents were recently given take to too long of a road trip to see the opporunity to speak to a many parts of West Virginia are as man who helped pioneer the far from diverse as is possible. -

Protesters Assemble

UNIVERSITY OF NORTH FLORIDA WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 1, 2012 Protesters Assemble Why they came to UNF PAGE 18 Student Fees Accumulate On The New year, new fee for Ospreys Grid PAGE 8 Photo Essay PAGE 14 INSIDE HODGEPODGE 2 Wednesday, February 1, 2012 SPINNAKER // UNFSPINNAKER.COM SPINNAKER // UNFSPINNAKER.COM Wednesday, February 1 , 2012 3 news 8 expressions 20 sports 24 Jan. 24 Criminal Mischief (Fine Arts Center Parking Garage) – An officer met with a victim who had been attempting to park her car in the ga- rage. The victim and another individual had been waiting for the spot, but the victim was closest, so she decided to take it. The other individual drove off while making derogatory comments toward the complainant. The complainant called UPD to report the incident but had to go to class POLICE before fully reporting. Upon returning to her vehicle, she found a key type scratch along the left rear panel of her car. The officer attempted to reach the defendant, but the number was not working. Investigation efforts are continuing. BEAT Check out more Police Beats online at unfspinnaker.com Jan. 25 Sick Person (Lot 18) – An offi- Jan. 25 Damaged Vehicle (Lot 18) – An of- Jan. 26 Backpack Theft (Lot 55) – An offi- Jan. 27 Sick Person (Osprey Fountains) cer observed the victim walking with ficer met with the complainant who said cer met with the victim who said his back- – An officer met with the subject and her bike and an unnamed white male. he was removing an immobilization boot pack and its contents were stolen while complainant. -

Chief FOIA Officer Weekly Report

FOIA Activity for the Week of December 16 - 29, 2011 Privacy Office January 3, 2012 Weekly FOIA Report I. Efficiency and Transparency-Steps taken to increase transparency and make forms and processes used by the general public more user-friendly, particularly web-based and FOIA related items: • On December 14, 2011, the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) Office of Citizenship and Office of Public Engagement held a meeting to discuss citizenship education strategies for older applicants. The conversation focused on barriers older applicants commonly encounter while preparing for citizenship, including the need for appropriate educational instruction, tools, and resources to help them prepare for the entire naturalization process. • On December 15, 2011, the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) posted a draft Request for Evidence template, I-129 L-1 “Intracompany Transferees: Qualifying Relationship/Ownership and Control/Doing Business,” for review and comment by stakeholders. Comments are due January 17, 2012. • On December 16, 2011, the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) conducted a teleconference in English and in Spanish to discuss the process of re-registration under the extension of Temporary Protected Status (TPS) for nationals of Honduras and Nicaragua. Honduran and Nicaraguan nationals must re- register for an extension of TPS by January 3, 2012. In view of the fast approaching the deadline, USCIS responded to stakeholder concerns regarding the re-registration process and to remind stakeholders of the importance of filing for TPS in a timely manner. • On December 20, 2011, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) created a new section in their online FOIA Library entitled “Office of Detention Oversight Detention Facility Compliance Inspections.” • On December 20, 2011, U.S.