An Overview of Incident Management Projects in the Netherlands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Utrecht CRFS Boundaries Options

City Region Food System Toolkit Assessing and planning sustainable city region food systems CITY REGION FOOD SYSTEM TOOLKIT TOOL/EXAMPLE Published by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and RUAF Foundation and Wilfrid Laurier University, Centre for Sustainable Food Systems May 2018 City Region Food System Toolkit Assessing and planning sustainable city region food systems Tool/Example: Utrecht CRFS Boundaries Options Author(s): Henk Renting, RUAF Foundation Project: RUAF CityFoodTools project Introduction to the joint programme This tool is part of the City Region Food Systems (CRFS) toolkit to assess and plan sustainable city region food systems. The toolkit has been developed by FAO, RUAF Foundation and Wilfrid Laurier University with the financial support of the German Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture and the Daniel and Nina Carasso Foundation. Link to programme website and toolbox http://www.fao.org/in-action/food-for-cities-programme/overview/what-we-do/en/ http://www.fao.org/in-action/food-for-cities-programme/toolkit/introduction/en/ http://www.ruaf.org/projects/developing-tools-mapping-and-assessing-sustainable-city- region-food-systems-cityfoodtools Tool summary: Brief description This tool compares the various options and considerations that define the boundaries for the City Region Food System of Utrecht. Expected outcome Definition of the CRFS boundaries for a specific city region Expected Output Comparison of different CRFS boundary options Scale of application City region Expertise required for Understanding of the local context, existing data availability and administrative application boundaries and mandates Examples of Utrecht (The Netherlands) application Year of development 2016 References - Tool description: This document compares the various options and considerations that define the boundaries for the Utrecht City Region. -

Parallel Air Temperature Measurements at the KNMI Observatory in De Bilt (The Netherlands) May 2003 - June 2005

Parallel air temperature measurements at the KNMI observatory in De Bilt (the Netherlands) May 2003 - June 2005 Theo Brandsma De Bilt, 2011 | Scientific report; WR 2011-01 Parallel air temperature measurements at the KNMI observatory in De Bilt (the Netherlands) May 2003 - June 2005 Version 1.0 Date March 14, 2011 Status Final final j Parallel air temperature measurements at the KNMI observatory in De Bilt (the Netherlands) May 2003 - June 2005 j March 14, 2011 Colofon Title Parallel air temperature measurements at the KNMI observatory in De Bilt (the Netherlands) May 2003 - June 2005 Authors Theo Brandsma — T +3130 220 66 93 Page 5 of 56 final j Parallel air temperature measurements at the KNMI observatory in De Bilt (the Netherlands) May 2003 - June 2005 j March 14, 2011 Page 6 of 56 final j Parallel air temperature measurements at the KNMI observatory in De Bilt (the Netherlands) May 2003 - June 2005 j March 14, 2011 Table of contents Foreword — 9 Summary — 11 1 Introduction — 13 1.1 Problem description — 13 1.2 Scope and objectives of the report — 14 2 Data and methods — 17 2.1 Site description and instrumentation — 17 2.1.1 Site description — 17 2.1.2 Instrumentation — 20 2.2 Methodology — 21 3 Results — 23 3.1 Climatic conditions during the experiment — 23 3.2 Monthly mean temperature differences — 23 3.3 Daily temperature differences — 24 3.4 Diurnal temperature cycle differences — 29 3.5 Diurnal wind speed cycle differences — 31 3.6 Wind direction dependent differences — 33 3.7 Vapor pressure differences — 37 3.8 Comparison of DB260 -

Meles Meles) Population at Eindegooi, the Netherlands

Defragmentation measures and the increase of a local European badger (Meles meles) population at Eindegooi, the Netherlands Hans (J.) Vink1, Rob C. van Apeldoorn2 & Hans (G.J.) Bekker3 1 National Forest Service, P.O. Box 1300, NL-3970 NG Driebergen, the Netherlands, e-mail: [email protected] 2 Alterra, Wageningen University and Research , P.O. Box 47, NL-6700 AA Wageningen, the Netherlands 3 Rijkswaterstaat, Centre for Transport and Navigation, P.O Box 5044, NL-2600 GA Delft, the Netherlands Abstract: Twenty four years’ data on European badger (Meles meles) and sett numbers have been collected by direct observation of a local population at Eindegooi, which straddles the Dutch provinces of Utrecht and Noord- Holland. The population has shown periods of both slow and exponential growth and spatial dynamics show colonization of the entire study area. Analysis of how population dynamics respond to defragmentation measures involving roads has been undertaken. This suggests that tunnels and other measures make a positive contribution. At low densities and during periods of slow growth these measures can increase the lifetime of reproducing indi- viduals and help badgers to safely disperse and colonize new habitat patches. Their positive effect on the popula- tion is illustrated by the fact that an individual’s mortality risk from traffic has remained more or less constant, despite the increasing number of cars on motorways and provincial roads that dissect the study area. Keywords: badger, Meles meles, population growth, badger friendly measures, traffic, roads. Introduction reducing fatal traffic accidents, but also on defragmenting isolated badger populations. The Dutch European badger (Meles meles) Initially organized at the local level, a national population is recovering after a strong decline defragmentation policy was initiated, which is in the second half of the last century (Wiertz still ongoing (Ministerie van Landbouw, Na- & Vink 1986, Wiertz 1992, Moll 2002, Moll tuurbeheer en Visserij 1990, Bekker & Canters 2005). -

Visibility Measurements in De Bilt and Schiphol

Visibility measurements in De Bilt and Schiphol. Bachelor thesis Utrecht University Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Research Utrecht http://www.imau.nl/ June 2010 “Cleaner air in Europe brings better views, more sunshine and warmer temperatures” Aldert J. van Beelen Supervisor: Dr. Aarnout J. van Delden Grand Canyon “hazy” Desert View at sunset. Will this view improve in the future? © A.J. van Beelen Content 1. Introduction………………………………………………………………3 1.1 Introduction. 1.2 Hypothesis 2. Theory……………………………………………………………………..5 2.1 Introduction to aerosol effects. 2.2 Decadal trends in surface solar radiation: global dimming. 2.3 Global brightening. 2.4 Dimming, brightening and climate. 2.5 Changes in human aerosol emissions. 2.6 Visibility trends over Europe. 2.7 Meteorological influences on visibility. 3. Methodology……………………………………………………………..15 3.1 Introduction to atmospheric visibility. 3.2 Visibility measurements at de Bilt and Schiphol. 3.2.1 Introduction. 3.2.2 Instrumentation. 3.2.3 Maintenance and placement. 3.2.4 Uncertainties and resolution. 3.2.5 Frequency and recording of measurements. 3.3 Methodology changes between 1955 and 2010 at de Bilt and Schiphol. 3.4 Methodology of this project. 4. Results & Discussion…………………………………………………..26 4.1 Visibility at De Bilt and Schiphol. 4.2 Visibility and changes in wind regime. 4.3 Visibility and changes in relative humidity. 4.4 Visibility changes, cloudiness and sunshine duration. 4.5 Visibility changes and temperature. 4.6 Visibility changes and the diurnal temperature range. 5. Summary and Conclusion…………………………………………….35 References………………………………………………………………………………..37 2 1. Introduction. 1.1 Introduction. This report describes and compares the visibility measurements at two locations in the Netherlands. -

Woerden Veenendaal UTRECHT Zeist Amersfoort Nieuwegein

! ! ! ! ! ! PROVINCIALE RUIMTELIJKE STRUCTUURVISIE ! 2013 - 2028 (HERIJKING 2016) ! Abcoude KAART 1 - EXPERIMENTEERRUIMTE ! ! ! ! Eiland van Schalkwijk (toelichtend) ! ! ! ! ! Eemnes ! 0 10 km ! Spakenburg ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Bunschoten Vastgesteld door Provinciale Staten van Utrecht op 12 december 2016 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Baarn ! Vinkeveen ! ! Mijdrecht ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Breukelen ! Soest ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Amersfoort ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Maarssen ! ! ! ! ! ! Bilthoven ! ! ! Leusden ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Vleuten De Bilt ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Zeist Woudenberg ! UTRECHT ! Woerden ! ! ! De Meern ! ! Bunnik ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Driebergen-Rijsenburg ! ! ! ! ! Mo! ntfoort ! Doorn Oudewater! Nieuwegein ! ! Houten Veenendaal ! IJsselstein ! ! ! ! Leersum ! ! ! Amerongen ! ! ! ! ! Vianen ! ! ! Wijk bij ! ! ! ! Duurstede ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Rhenen ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! AFDELING FYSIEKE LEEFOMGEVING, TEAM GIS ONDERGROND: © 2017, DIENST VOOR HET KADASTER EN OPENBARE REGISTERS, APELDOORN 12-12-2016 PRS PROVINCIALE RUIMTELIJKE STRUCTUURVISIE 2013 - 2028 (HERIJKING 2016) Abcoude KAART 2 - BODEM veengebied kwetsbaar voor oxidatie (toelichtend) Eemnes Spakenburg duurzaam gebruik van de ondergrond veengebied gevoelig voor bodemdaling Bunschoten 0 10 km Vastgesteld door Provinciale Staten van Utrecht op 12 december 2016 Vinkeveen Baarn Mijdrecht Breukelen Soest Amersfoort Maarssen Bilthoven Leusden Vleuten De Bilt Zeist Woudenberg UTRECHT Woerden De Meern Bunnik Driebergen-Rijsenburg Montfoort Doorn Oudewater Nieuwegein Houten -

Project: Bureauonderzoek, Ensahlaan 2A Te Bilthoven, Gemeente De Bilt Projectnummer: S180016

Bureau – en Inventariserend Veldonderzoek, karterend booronderzoek Ensahlaan 2a te Bilthoven gemeente De Bilt Opdrachtgever Dhr. F. Nederveen Hezer Enghweg 17 Projectleider 3734 GM Den Dolder drs. M. Petterson Projectnummer Autorisatie Paraaf Datum Synthegra Rapport S180016 drs. J. Krist 12-06-2018 Synthegra B.V., Olmenlaan 6a, NL-3833 AV Leusden Telefoon +31 (0)88 81 81 981, Internet: www.synthegra.nl Project: Bureauonderzoek, Ensahlaan 2a te Bilthoven, gemeente De Bilt Projectnummer: S180016 COLOFON Opdrachtgever : Bilthoven Project : Ensahlaan 2a te Bilthoven Projectnummer : S180016 Titel : Bureauonderzoek, Ensahlaan 2a te Bilthoven Datum : 12-06-2018 Projectleider : drs. M. Petterson Auteurs : drs. M. Petterson Autorisatie : drs. J. Krist Afbeeldingen : Synthegra B.V., tenzij anders vermeld Druk : Synthegra B.V., Leusden ISSN : 1874-9771 Synthegra B.V. is gecertificeerd voor de BRL 4000 protocollen 4001 t/m 4004 (landbodems) Synthegra B.V. Synthegra B.V., Olmenlaan 6a, NL-3833 AV Leusden Telefoon +31 (0)88 81 81 981, Internet: www.synthegra.nl © Synthegra B.V., 2018 © Synthegra B.V., Olmenlaan 6a, NL-3833 AV Leusden 2 van 30 Project: Bureauonderzoek, Ensahlaan 2a te Bilthoven, gemeente De Bilt Projectnummer: S180016 INHOUD ADMINISTRATIEVE GEGEVENS 4 SAMENVATTING 5 Inleiding 5 Specifieke archeologische verwachting bureauonderzoek 5 Conclusie en aanbeveling 6 1 INLEIDING 7 1.1 Onderzoekskader 7 1.2 Onderzoeksdoel en vraagstellingen 7 1.3 Ligging en huidige situatie plangebied 8 1.4 Toekomstige situatie plangebied 8 2 BUREAUONDERZOEK -

Veenweg 10 - Bosweg/Paardenkop - Achterbergsestraatweg

ERVENCONSULENT BOUWEN MET RUIMTELIJKE KWALITEIT Veenweg 10 - Bosweg/Paardenkop - Achterbergsestraatweg INTRODUCTIE Aanleiding De eigenaar van de locatie Veenweg 10 wil graag gebruik maken van de ruimte- voor-ruimte regeling(RvR). Door de sloop van de stallen ontstaat er een bouwrecht voor 2 woonbestemmingen. Gezien de aanwezigheid van de hoogspanningslijn is het niet wenselijk om deze twee nieuwe woningen op locatie te bouwen. De gemeente Rhenen is op zoek gegaan naar initiatiefnemers die gebruik willen maken van dit bouwrecht. B&W is akkoord met het principeverzoek en heeft in haar besluit op 20 juni 2016 voorwaarden gesteld aan de RvR voor het perceel Veenweg 10. De gemeente stelt onder meer als eis dat voor alle drie de locaties waarop RvR-regeling van toepassing is, een door Landschap Erfgoed Utrecht (LEU) goedgekeurd inpassingsplan wordt opgesteld. Proces In overleg met O-gen, LEU en de gemeente is besloten tot een ontwerpsessie-dag met alle betrokkenen in drie afzonderlijke sessies van elk maximaal 2 uur. Hierbij leveren de ervenconsulenten zowel een procedurele als inhoudelijke bijdrage. Het vraagstuk van de inpassing wordt in de voorfase al integraal benaderd, een efficiënte manier om tot een goed ontwerp te komen. Deelnemers aan de sessies zijn: provincie Utrecht/O-gen, gemeente Rhenen, de ervenconsulenten, Land Plus, DORPenLANDadvies en de eigenaren van elke locatie. De resultaten van deze schetssessies zijn verwerkt in de adviezen van Land Plus. Tijdens deze aanpassingsronde heeft er nog tussentijdse afstemming met de ervenconsulenten plaats gevonden. Nadien heeft O-gen gevraagd om alsnog advies uit te brengen over deze drie locaties. Dit is het advies wat nu voor u ligt. -

Factsheet Zon-PV U10-U16 PDF Document

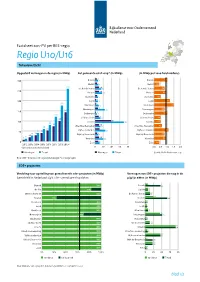

Factsheet zon-PV per RES-regio Regio U10/U16 Totaaloverzicht Opgesteld vermogen in de regio (in MWp) Per gemeente eind 2019* (in MWp) (In MWp per 1000 huishoudens) 4 Bunnik 7 Bunnik 1,0 5 De Bilt 8 De Bilt 0,4 258 10 De Ronde Venen 15 De Ronde Venen 0,8 10 Houten 17 Houten 0,9 5 IJsselstein 7 IJsselstein 0,5 3 Lopik 7 Lopik 1,2 176 3 Montfoort 9 Montfoort 1,5 7 Nieuwegein 24 Nieuwegein 0,8 142 Oudewater 2 Oudewater 1,0 120 5 Stichtse Vecht 9 Stichtse Vecht 0,5 100 13 Utrecht 39 Utrecht 0,5 80 70 74 10 0,6 60 Utrechtse Heuvelrug 13 Utrechtse Heuvelrug 53 11 Vijeerenlanden 25 Vijeerenlanden 1,1 41 41 28 29 5 0,8 20 Wijk bij Duurstede 8 Wijk bij Duurstede 8 12 10 Woerden 20 Woerden 0,9 8 Zeist 11 Zeist 0,4 * *(per einde van het kalenderjaar) , , , , , Woningen Totaal Woningen Totaal Gemiddeld in Nederland: 0,9 Bron: CBS – Zonnestroom: opgesteld vermogen *voorlopige cijfers SDE+ projecten Verdeling naar opstelling van gerealiseerde sde+ projecten (in MWp) Vermogen van SDE+ projecten die nog in de Gemiddeld in Nederland: 63% SDE+ gerealiseerd op daken pijplijn zitten (in MWp) 6 Bunnik 100% Bunnik 37 7 De Bilt 83% De Bilt 7 12 De Ronde Venen 100% De Ronde Venen 12 20 Houten 24% Houten 54 3 IJsselstein 100% IJsselstein 3 4 Lopik 100% Lopik 4 7 Montfoort 100% Montfoort 7 36 Nieuwegein 70% Nieuwegein 41 3 Oudewater 100% Oudewater 3 11 Stichtse Vecht 100% Stichtse Vecht 11 74 Utrecht 100% Utrecht 74 5 Utrechtse Heuvelrug 100% Utrechtse Heuvelrug 6 37 Vijeerenlanden 100% Vijeerenlanden 37 3 Wijk bij Duurstede 100% Wijk bij Duurstede -

Woonvisie (Pdf)

Woonvisie 2025 DE RONDE VENEN POSTADRES Postbus 250 T 0297 29 16 16 3640 AG Mijdrecht F 0297 28 42 81 BEZOEKADRES Croonstadtlaan 111 E [email protected] 3641 AL Mijdrecht I www.derondevenen.nl AUTEUR(S) Emily Joynes DATUM Mei 2017, gewijzigd vastgesteld maart 2020 STATUS Vastgesteld door gemeenteraad Woonvisie De Ronde Venen Voorwoord Of je nu vaart, fietst, loopt of eenvoudigweg naar school of werk gaat. De Ronde Venen is prachtig! En telkens verbaas ik me er weer over hoe snel ik in de stad ben. Binnen een half uur sta ik op de Dam in Amsterdam of onder de Dom in Utrecht. Dat maakt De Ronde Venen een unieke plek. Je kunt er thuis komen en je rust vinden. En tegelijkertijd gonst het ook binnen de gemeente van bedrijvigheid. Wie door de gemeente rijdt, ziet overal bouwactiviteiten. In 2016 is het startsein gegeven voor de bouw van drie grote woningbouwprojecten in de gemeente: Vinkeveld, De Maricken en Land van Winkel. Er wordt volop gebouwd voor alle inkomens en leeftijden. Koop en sociale huur. Toegankelijke woningen voor starters. Woningen voor mensen die een volgende woonstap zetten. Comfortabele levensbestendige woningen voor senioren. Voor iedereen is er een woning. Onze jongeren blijven graag in de gemeente wonen of keren terug na hun studie. Jonge gezinnen die de stad ontvluchten vinden hier ruimte en betaalbare woningen. Ouderen kunnen hier in hun vertrouwde omgeving blijven wonen in passende woonruimte. En met het aantrekken van jonge gezinnen uit de regio blijven we een vitale en economische sterke gemeente. Wij blijven werken aan een goed woonaanbod. -

Utrechtse Heuvelrug – Wijk Bij Duurstede – Zeist RSD – Biga – Regionale Cliëntenraad

Samenvatting input op uitgangspuntennotitie Strategische Kaders Participatiewet Bunnik – De Bilt – Utrechtse Heuvelrug – Wijk bij Duurstede – Zeist RSD – Biga – Regionale Cliëntenraad Adviesraad Gemeenteraad Bunnik Uitgangspunten Gemeenteraad is worden ondersteund geconsulteerd. Hoe komen tot de uitvoering (wie wordt waarvoor verantwoordelijk) Bepaal wat lokaal en wat regionaal moet worden gerealiseerd. Waar ligt de regie en waar ligt het aanspreekpunt. Is het hebben van een dagbesteding/werk leidend of de regie op welzijn/krijgen van integrale hulp wat bij de gemeente is belegd. Eén gezin, één plan, één regisseur: een prima principe, maar moeilijk te realiseren. Overweeg om hierbij in koppels te werken met een eerste en tweede contactpersoon. Dit vergemakkelijkt het vervangen aanzienlijk en is duidelijk voor degene die ondersteuning krijgt. Hoeveel doorzettingsmacht is er om problemen in samenhang op te lossen. Taalgebruik notitie niet eenvoudig. 1 Adviesraad Gemeenteraad De Bilt De adviesraad Sociaal Er is gevraagd om een Domein kan zich bijlage met cijfermatige grotendeels vinden in onderbouwing voor de het gestelde in de 3 doelgroepen toe te Uitgangspuntennotitie voegen. De adviesraad adviseert Er is aangegeven dat de de gemeente om samenstelling van het initiatief te nemen om klantenbestand in de een centraal meldpunt toekomst weer kan schulden in te richten veranderen. Hoe wordt waarbij schulden vanuit ervoor gezorgd dat de verschillende organisatie op die schuldeisers worden veranderingen in kan geregistreerd. spelen? Op pg. 10 staat dat Een groot deel van de “inwoners met raad is het met het arbeidsvermogen mee uitgangspunt eens dat dienen te doen, een we de prioriteit in tegenprestatie dienen ondersteuning en te leveren en actief begeleiding (en de stappen richting de bijbehorende middelen) arbeidsmarkt dienen te leggen bij doelgroep 2. -

Amersfoort De Bilt/Zeist

tijd over hebben bezoeken we ook het AMERSFOORT Kennemermeer, waar we diverse lijsters en andere zangvogels kunnen vinden. We vertrekken per auto om 8.00 uur vanaf Voor alle excursies kunt u zich opgeven bij CNME Schothorst. Benzinekosten worden René de Waal, renedewaal@vogelwacht- verrekend met de chauffeur. utrecht.nl of tel. 06-49121619 (na zes uur). Zaterdag 6 september Vrijdag 19 december Excursie Hilversumse Bovenmeent Uilenexcursie Den Treek De Hilversumse Bovenmeent is de polder Afgelopen jaar kon deze traditionele excur- ten zuiden van het Naardermeer. Dit was sie helaas geen doorgang vinden, maar dit vroeger landbouwgrond. Natuurmonumen- jaar proberen we het weer! We gaan in ten heeft hier ondiepe plassen gemaakt. Nu landgoed Den Treek luisteren naar bosuilen, heeft het gebied een enorme aantrekkings- die zich in deze tijd laten horen. kracht op allerlei soorten vogels. Voor veel We verzamelen om 21.30 uur bij restaurant vogelliefhebbers is dit hun favoriete plek om Bavoort in Leusden, aan het begin van de vogels te spotten. We verkennen het gebied Treekerweg. te voet. Wandelschoenen aanbevolen! We vertrekken per auto om 7.30 uur vanaf CNME Schothorst. Benzinekosten worden DE BILT/ZEIST verrekend met de chauffeur. 10-12 oktober Zaterdag 6 december Weekendexcursie Zeeland Excursie Camping “De Zeven Linden” Onze jaarlijkse weekendexcursie wordt dit Op camping “De Zeven Linden” is het in de jaar gehouden in Zeeland (Schouwen). We winter goed vogelen. Er is een goede kans verblijven in Haamstede en bezoeken van op behoorlijke aantallen kruisbekken, appel- daaruit de Brouwersdam, de inlagen langs vinken, kepen en vinken. En natuurlijk zijn de Oosterschelde, alsmede Plan Tureluur. -

Naam Voornaam Pl

Klas Roepnaam Tussenv Achternaam Woonplaats H5a Tijn de Haas Utrecht H5a Kamiel Hallmann Utrecht H5a Henk Hol ZEIST H5a Rune Keesmaat Zeist H5a Vienna Kerkhove Zeist H5a Ivo van Keulen Soesterberg H5a Roselinde Kooistra ZEIST H5a Luca Kroon Zeist H5a Filip van Lunteren LEERSUM H5a Damian Meeuwesse DRIEBERGEN RIJSENBURG H5a Kim Muller Odijk H5a Yannick Op 't Hof Zeist H5a Joy Pleijlar Zeist H5a Romijn Reerink Utrecht H5a Hanna Rijnbeek Zeist H5a Suzanne van Roshum Odijk H5a Letja Slakhorst Driebergen-Rijsenburg H5a Nilasha Sloeserwij Driebergen-Rijsenburg H5a Jochem Steeman Leersum H5a Valentijn Tigchelaar Zeist H5b Isabelle Aalten Zeist H5b Tim van Beest Zeist H5b Philip de Boer Zeist H5b Merel Bruijnzeels Maarn H5b Ole Bukman Utrecht H5b Nienke van Denderen Austerlitz H5b Mees Dooyeweerd Zeist H5b Beau Groothuis Austerlitz H5b Luuk Gueret De Bilt H5b Milou Hakkert Zeist H5b Kylie Hoogeveen Driebergen-Rijsenburg H5b Anouk Huijgen Utrecht H5b Kayo Izarin Driebergen-Rijsenburg H5b Jelle Kessels Utrecht H5b Jan-Willem Klerkx Zeist H5b Fabio Lambeek Soesterberg H5b Roxan van Lochem Utrecht H5b Lars Mahler Zeist H5b Josine Savelsbergh Zeist H5b Jonah Stekelenburg Utrecht H5b Romee Stok Driebergen-Rijsenburg H5b Robin Voorboom De Bilt H5b Sara van der Wijngaard Zeist H5c Emma de Beijer De Bilt H5c Manon van Bennekom Bunnik H5c Andrea van de Bunt Werkhoven H5c Jannemijn Carlier Driebergen-Rijsenburg H5c Okke Dries Maarn H5c Daan Duifhuis Zeist H5c Kai van Gaalen Utrecht H5c Mees Hoffmann Utrecht H5c Kreychelle Houtman Utrecht H5c Raoul Janssen