Epitaph, Dirge, and Ashes in Late Modernist Poetry by Fedor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PINTER Harold – Ashes to Ashes

CENERI ALLE CENERI (Ashes to Ashes) Commedia Di HAROLD PINTER PERSONAGGI Devlin un uomo sui quarantanni Rebecca una donna sui quarant'anni L'azione si svolge ai giorni nostri. Commedia formattata da Cateragia per il sito GTTEMPO A house in the country. Ground floor room. A large window. Garden beyond. Two armchairs. Two lamps. Early evening. Summer. The room darkens during the course of the play. The lamplight intensifies. By the end of the play the room and the garden beyond are only dimly defined. The lamplight has become very bright but does not illumine the room. Devlin standing with drink. Rebecca sitting. Silence. Rebecca - Well... for example... he would stand over me and clench his fist. And then he'd put his other hand on my neck and grip it and bring my head towards him. His fist... grazed my mouth. And he'd say, «Kiss my fist». Devlin - And did you ? Rebecca - Oh yes. I kissed his fist. The knuckles. And then he'd open his hand and give me the palm of his hand... to kiss... which I kissed. (Pause). And then I would speak. Devlin - What did you say? You said what? What did you say ? Pause. Rebecca - I said, «Put your hand round my throat». I murmured it through his hand, as I was kissing it, but he heard my voice, he heard it through his hand, he felt my voice in his hand, he heard it there. Silence. Devlin - And did he? Did he put his hand round your throat ? Rebecca - Oh yes. He did. -

Jon Clark Lighting Designer

Jon Clark Lighting Designer Jon is an award-winning lighting designer, based in the United Kingdom. He studied theatre design at Bretton Hall College, Leeds University. Jon won the Olivier Award for Best Lighting Design in 2019 and is nominated for the 2020 Tony Award for Best Lighting Design of a Play, both for his work on THE INHERITANCE in the West End and on Broadway respectively. He was nominated for a 2019 Drama Desk Award in New York for Outstanding Lighting Design, for his work on THE JUNGLE. Jon, along with the cast and creative team, recently won an Obie Award in New York, also for THE JUNGLE. He is the recipient of Green Room Australia Award for Best Opera Lighting Design for KING ROGER at the Sydney Opera House and won a Knight of Illumination Award for THREE DAYS OF RAIN in the West End in 2009. Jon is an associate artist of the RSC. Theatre 2020 A CHRISTMAS CAROL Bridge Theatre, London 2020 BEAT THE DEVIL & TALKING HEADS Bridge Theatre, London 2020 THE LEHMAN TRILOGY Nederlander Theatre Broadway, Piccadilly Theatre, London (2019), Park Avenue Armory, New York (2019), National Theatre, London (Premiere 2018) 2019 CYRANO DE BERGERAC Playhouse Theatre, London 2019 THE INHERITANCE Ethel Barrymore Theatre, Broadway Noel Coward Theatre, London (2018), Young Vic, London (Premiere, 2018) 2019 BETRAYAL Bernard B. Jacobs Theater, Broadway Harold Pinter Theatre, London (Premiere) 2019 EVITA Regents Park Open Air Theatre, London 2019 A GERMAN LIFE Bridge Theatre, London 2019 TREE Young Vic, London Manchester International Festival, -

THE POLITICS of HAROLD PINTER's PLAYS Ruben

THE POLITICS OF HAROLD PINTER’S PLAYS Ruben Moi One of the 2005 Nobel Laureate Harold Pinter’s recent plays, The New World Order, from 1993, offers a self-glorifying exchange between two torturists: Lionel: I feel so pure. Des: Well, you’re right. You’re right to feel pure. You know why? Lionel: Why? Des: Because you’re keeping the world clean for democracies.1 The ironic equivocation in the last sentence plays on, as does the title, the deployment of torture in the defence of democracy, a dehumanis- ing act that in its very execution undermines the principles of liberty, equality and fraternity – the unassailable values upon which the concept of democracy has traditionally been founded. Obviously, the excerpt also parodies individual self-righteousness and political ideal- ism at the present time when the menace to human rights and the established form of government in most of the western world appears, perhaps, to loom larger within the realms of democracy than in any alternative world order, at least according to Pinter. The New World Order is only one of several shorter plays from the latter period of his career that hardly leave anybody in doubt about their meaning and message – a rather clear-cut contrast to the thought-provoking ambi- guities and polysemy of his plays of the 1950s and -60s, which made such an impact on the stage of its day. Readers and audiences of Pinter’s plays who are perplexed about the reorientations of his career and the status of his art appear justified. The protean changes of Pinter’s art raise a series of questions about aesthetic autonomy and political commitment. -

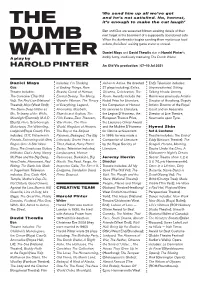

The Dumb Waiter

‘We send him up all we’ve got and he’s not satisfied. No, honest, THE it’s enough to make the cat laugh’ Ben and Gus are seasoned hitmen awaiting details of their next target in the basement of a supposedly abandoned cafe. DUMB When the dumbwaiter begins sending them mysterious food orders, the killers’ waiting game starts to unravel. Daniel Mays and David Thewlis star in Harold Pinter’s WAITER darkly funny, insidiously menacing The Dumb Waiter. A play by HAROLD PINTER An Old Vic production | 07–10 Jul 2021 Daniel Mays includes: I’m Thinking Ashes to Ashes. He directed End). Television includes: Gus of Ending Things, Rare 27 plays including: Exiles, Unprecedented, Sitting, Theatre includes: Beasts, Guest of Honour, Oleanna, Celebration, The Talking Heads. Jeremy The Caretaker (The Old Eternal Beauty, The Mercy, Room. Awards include the Herrin was previously Artistic Vic); The Red Lion (National Wonder Woman, The Theory Nobel Prize for Literature, Director of Headlong, Deputy Theatre); Mojo (West End); of Everything, Legend, the Companion of Honour Artistic Director of the Royal The Same Deep Water as Anomalisa, Macbeth, for services to Literature, Court and an Associate Me, Trelawny of the Wells, Stonehearst Asylum, The the Legion D’Honneur, the Director at Live Theatre, Moonlight (Donmar); M.A.D Fifth Estate, Zero Theorem, European Theatre Prize, Newcastle upon Tyne. (Bush); Hero, Scarborough, War Horse, The New the Laurence Olivier Award Motortown, The Winterling, World, Kingdom of Heaven, and the Molière D’Honneur Hyemi Shin Ladybird (Royal Court). Film The Boy in the Striped for lifetime achievement. -

Harold Pinter's Ashes to Ashes*

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO GRANDE DO SUL INSTITUTO DE LETRAS PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM LETRAS Harold Pinter’s Ashes to Ashes* Marta Ramos Oliveira Dissertação realizada sob a orientação do Dr. Ubiratan Paiva de Oliveira Porto Alegre 1999 * Trabalho parcialmente financiado pelo Conselho Nacional do Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq). To my mother and those who came before and those who are still to come Because you don’t know where [the pen] had been. You don’t know how many other hands have held it, how many other hands have written with it, what other people have been doing with it. You know nothing of its history. You know nothing of its parents’ history. - DEVLIN TODESFUGE Schwarze Milch der Frühe wir trinken sie abends Wir trinken sie mittags und morgens wir trinken sie nachts Wir trinken und trinken Wir schaufeln ein Grab in den Lüften da liegt man nicht eng Ein Mann wohnt im Haus der spielt mit den Schlangen der schreibt Der schreibt wenn es dunkelt nach Deutschland dein goldenes Haar Margarete Er schreibt es und tritt vor das Haus und es blitzen die Sterne er pfeift seine Rüden herbei Er pfeift seine Juden hervor läßt schaufeln ein Grab in der Erde Er befiehlt uns spielt auf nun zum Tanz Schwarze Milch der Frühe wir trinken dich nachts Wir trinken sie morgens und mittags und wir trinken dich abends Wir trinken und trinken Ein Mann wohnt im Haus der spielt mit den Schlangen der schreibt Der schreibt wenn es dunkelt nach Deutschland dein goldenes Haar Margarete Dein aschenes Haar Sulamith wir schaufeln ein Grab in -

Harold Pinter: from Poetics to Politics

Edebiyat Dergisi, Yıl:2006, Sayı: 15, s.59-66 HAROLD PINTER: FROM POETICS TO POLITICS Dilek İNAN (PhD, Warwick Uniuersity) Balıkesir Üniuers!tesl Abstract Harold Pinter was gluen the Nobel Prize /or Literature in 2005 for his contributlons to Brltfsh and contemporary drama. Pinter has been a theatrical institution for hal/ a century, he has reuolutionised his theatre by being a conscientious objector in pub/ic and a politlcaf actiuist since the 1980s. He has explored di/ferent genres lncluding prose and poetry, plays for stage, radio and screen. His crossouer from one medium to another, his deliberate decision to write /or more than one medlum, has gluen him the opportunity to reach the potential mass audience. He has shocked bewifdered, disappointed, and astonished audiences and critics. He swiftly became accepted as Britain's premier dramatist. This paper traces the euolution that Plnter has gone through /rom the early 1950s until the 2000s. Additionatly, the paper Identifles Harofd Pinter's 'Pinteresque' style - a term whlch enters English Language and Literature after him and also exemplify and reason Plnter's change in his styfe from poetical to politicaf. Key Words: Harold Pinter, British Theatre, Politica/ Theatre, Language Özet İngiliz ue Dünya Tiyatrosuna katkılarından dolayı 2005 yılında Harold Pinter'a Nobel Edebiyat ödülü uerilmiştir. Pinter yarım asırdır tiyatroya hizmet . etmektedir, 1980lerden günümüze kadar, tiyatro kimliğini politik kimliğiyle zenginleştirmiştir. Yarım asırlık dönemde, düzyazı, şiir, tiyatro oyunu, radyo oyunu ue film senaryosu gibi farklı türlerde eserler üretmiştir. Edebiyat türleri arasındaki geçişleri ue değişimleri O'nun her zaman daha fazla izleyici kitlesine ulaşmasına imkan vermiştir. -

Kane, Pinter and Theatre As Monument to Loss in the 1990S

This is a repository copy of How to Mourn - Kane, Pinter and Theatre as Monument to Loss in the 1990s. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/86649/ Version: Accepted Version Book Section: Taylor-Batty, MJ (2014) How to Mourn - Kane, Pinter and Theatre as Monument to Loss in the 1990s. In: Aragay, M and Monforte, E, (eds.) Ethical Speculations in Contemporary British Theatre. Palgrave Macmillan , pp. 59-75. ISBN 978-1137297563 https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137297570 © Palgrave Macmillan 2014. This is an author produced version of a chapter published in Ethical Speculations in Contemporary British Theatre. Reproduced by permission of the publisher. Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ -

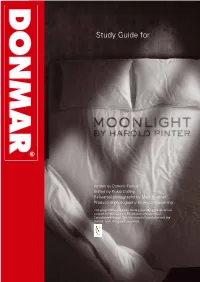

Study Guide For

Study Guide for Written by Dominic Francis Edited by Rosie Dalling Rehearsal photography by Marc Brenner Production photography by Hugo Glendining This programme has been made possible by the generous support of Noel Coward Foundation and Universal Consolidated Group, The Mackintosh Foundation and the Harold Hyam Wingate Foundation 1 Contents Section 1 Cast and Creative Team Section 2 An introduction to Harold Pinter and his work Biography Harold Pinter’s schooldays MOONLIGHT Section 3 Inside the rehearsal room Resident Assistant Director Simon Evan’s rehearsal diary An interview with Simon Evans Section 4 MOONLIGHT in performance Practical exercises based on an extract from the beginning of the play Questions on the production and further practical work Section 5 Ideas for further study Reading and research Bibliography Endnotes 2 section 1 Cast and Creative Team Cast (in order of appearance) LISA DIVENEY DAVID BRADLEY DEBORAH DANIEL MAYS Bridget, a girl of Andy, a man FINDLAY Jake, a man of sixteen, a ghost, in his fifties, Bel, a woman twenty-eight, Andy Andy and Bel’s a retired civil of fifty, Andy’s and Bel’s eldest dead daughter. servant, bedbound long-suffering wife son. and dying of who sits at his an undisclosed bedside enduring terminal illness. his vindictive He waits in vain interrogation. for his estranged adult children to visit him. LIAM GARRIGAN CAROL ROYLE PAUL SHELLEY Fred, a man of Maria, a woman Ralph, a man in twenty-seven, of fifty, an old his fifties, Maria’s Andy and Bel’s friend of Bel’s husband, a former younger son. -

Feminine Melancholia in Harold Pinter's Ashes to Ashes

ISSN 1798-4769 Journal of Language Teaching and Research, Vol. 4, No. 3, pp. 536-544, May 2013 © 2013 ACADEMY PUBLISHER Manufactured in Finland. doi:10.4304/jltr.4.3.536-544 Feminine Melancholia in Harold Pinter's Ashes to Ashes Motahareh Sadat Peyambarpour English Department, Faculty of Foreign Languages, University of Isfahan, Iran Helen Ouliaeinia English Department, Faculty of Foreign Languages, University of Isfahan, Iran Abstract—Harold Pinter's Ashes to Ashes (1996) addresses different notions such as gender, politics, masculinity and language. Julia Kristeva's theory of melancholia and depression, as one of the most important psychological theories, strives to elaborate the condition of melancholic subject. She remarks that the melancholic subject, unable to share her / his melancholia with others, suffers from an unsignified sense of loss which causes her / his psyche to be wounded. Ashes to Ashes explores the melancholic condition of the female protagonist who suffers from an unsignified sense of loss. This study is an attempt to trace the signs of melancholia — regarding Kristeva's theory of melancholia — which reveal through Rebecca's fragmented dialogues, dream-like memories and tense monologues. Index Terms—Harold Pinter, Ashes to Ashes, Julia Kristeva, the melancholic subject, loss, language I. INTRODUCTION Widespread interest in Julia Kristeva, a professor of linguistics, stems from her concerns with different disciplines such as linguistics, psychology, feminis m and politics. Kristeva is a prolific writer and a complex thinker whose theory of melancholia and depression has won her lasting fame among psychoanalytic theorists. Her psychoanalysis proposes a loss theory of melancholia in the tradition of Freud's "Mourning and Melancholia". -

Speech Rhythm As a Comic Device in Plays by Harold Pinter, in Particular Old Times and Ashes to Ashes

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by NORA - Norwegian Open Research Archives Speech Rhythm as a Comic Device in Plays by Harold Pinter, in particular Old Times and Ashes to Ashes Thomas Lie Nygaard Thesis submitted to hovedfagsgrad The Department of English University of Bergen November 2002 At destruction and famine you shall laugh, and shall not fear the wild animals of the earth. The Book of Job 5: 22 TITUS: Ha, ha, ha! MARCUS: Why dost thou laugh? it fits not with this hour. TITUS: Why, I have not another tear to shed: [...] William Shakespeare. Titus Andronicus. III.i.264-66 BILL: I’ll ... tell you ... the truth. HARRY: Oh, for God’s sake, don’t be ridiculous. Harold Pinter. The Collection. P2: 144. i Acknowledgements First of all I would like to give a special thanks to my supervisor Stuart Sillars for believing in me. He has helped me clarify my ideas and guided me in my work by pushing me forward. At the same time letting me stick to my own speed through the various stages of the process. Other members of the staff at the English department have also contributed with comments and loan of books. My fellow hovedfag students at the English department in Bergen have contributed moral support and never-ending relevant discussions. And also the opposite. My friends have been kind to let me discuss my project with them, although I suspect it has been tedious at times. Finally, I owe a warm thanks to my parents and my sisters for encouragement and motivation. -

Politics and Harold Pinter

Victoria Marie Baldwin ‘Look for the truth and tell it’: Politics and Harold Pinter MPhil (B) Drama and Theatre Arts University of Birmingham 24th July 2009 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ‘Look for the truth and tell it’: Politics and Harold Pinter Contents Introduction Politics page 1 Chapter One ‘I told him no one. No one at all’: Gender politics in Old Times’ page 9 Chapter Two ‘You Brought It Upon Yourself’: responsibility in Ashes to Ashes page 27 Chapter Three ‘Art, Truth and Politics’: Pinter Today page 40 Conclusion Is Pinter a ‘political playwright’? page 53 Appendices Bibliography Introduction: Politics ‘I think in the early days […] I was a political playwright of a kind’ (Pinter, 1989, cit. Gussow, 1994: 82). My interest in Pinter as an area of research stems from this assertion. Despite being a prominent playwright, Pinter’s celebrity in recent times has been as much acknowledged for his contribution to political debate as to his involvement with contemporary drama. The Independent newspaper in December 1998 described Pinter as ‘playwright and human rights activist’ (Derbyshire, 2001c: 232) and it seems that his latter role is most certainly assisted by his fame as the former. -

The Ambiguity of Self & Identity in Pinter's Comedy of Menace

European Journal of Scientific Research ISSN 1450-216X Vol.58 No.4 (2011), pp.593-598 © EuroJournals Publishing, Inc. 2011 http://www.eurojournals.com/ejsr.htm The Ambiguity of Self & Identity in Pinter's Comedy of Menace Saeid Rahimipoor Moddares TTC, Ilam Education Organization, Pazohesh St. Ilam, Iran E-mail: [email protected] Tel: +98 9183428011 Abstract Harold Pinter, the profound and illustrious playwright of the twentieth century, has been concerned with the existential problems of man in a hostile universe. Through plays of different types and his own idiosyncratic style, in his comedy of menace, he targets the question of self and identity, the major obsession of modern man which has been violated by the menaces of different types. In this article, I have scrutinized the birthday party, Pinter's major comedy of menace, to show how physical, psychological, and mental types of menace aroused by the violation, deprivation, and exploitation of man's Intra and Inter relationships have culminated in his blurred vision of his self and identity. Keywords: Menace, Self & Identity, Pinter Introduction Harold Pinter, the outstanding 20 th century English playwright, through his oeuvre and his idiosyncratic style has contributed a lot in revelation of the existential problems of mankind. Alienation, sense of disintegration, evasiveness, domination, violation of identity and sense of self are major themes depicted in his plays. His plays have been studied very often. Many critics have tried to classify them depending on their intended themes as plays of menace, identity, memory, and political plays which are all in pursuit of highlighting and revealing specific tenets of the human existence.