Harold Pinter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JM Coetzee and Mathematics Peter Johnston

1 'Presences of the Infinite': J. M. Coetzee and Mathematics Peter Johnston PhD Royal Holloway University of London 2 Declaration of Authorship I, Peter Johnston, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Dated: 3 Abstract This thesis articulates the resonances between J. M. Coetzee's lifelong engagement with mathematics and his practice as a novelist, critic, and poet. Though the critical discourse surrounding Coetzee's literary work continues to flourish, and though the basic details of his background in mathematics are now widely acknowledged, his inheritance from that background has not yet been the subject of a comprehensive and mathematically- literate account. In providing such an account, I propose that these two strands of his intellectual trajectory not only developed in parallel, but together engendered several of the characteristic qualities of his finest work. The structure of the thesis is essentially thematic, but is also broadly chronological. Chapter 1 focuses on Coetzee's poetry, charting the increasing involvement of mathematical concepts and methods in his practice and poetics between 1958 and 1979. Chapter 2 situates his master's thesis alongside archival materials from the early stages of his academic career, and thus traces the development of his philosophical interest in the migration of quantificatory metaphors into other conceptual domains. Concentrating on his doctoral thesis and a series of contemporaneous reviews, essays, and lecture notes, Chapter 3 details the calculated ambivalence with which he therein articulates, adopts, and challenges various statistical methods designed to disclose objective truth. -

The Best According To

Books | The best according to... http://books.guardian.co.uk/print/0,,32972479299819,00.html The best according to... Interviews by Stephen Moss Friday February 23, 2007 Guardian Andrew Motion Poet laureate Choosing the greatest living writer is a harmless parlour game, but it might prove more than that if it provokes people into reading whoever gets the call. What makes a great writer? Philosophical depth, quality of writing, range, ability to move between registers, and the power to influence other writers and the age in which we live. Amis is a wonderful writer and incredibly influential. Whatever people feel about his work, they must surely be impressed by its ambition and concentration. But in terms of calling him a "great" writer, let's look again in 20 years. It would be invidious for me to choose one name, but Harold Pinter, VS Naipaul, Doris Lessing, Michael Longley, John Berger and Tom Stoppard would all be in the frame. AS Byatt Novelist Greatness lies in either (or both) saying something that nobody has said before, or saying it in a way that no one has said it. You need to be able to do something with the English language that no one else does. A great writer tells you something that appears to you to be new, but then you realise that you always knew it. Great writing should make you rethink the world, not reflect current reality. Amis writes wonderful sentences, but he writes too many wonderful sentences one after another. I met a taxi driver the other day who thought that. -

Albion Full Cast Announced

Press release: Thursday 2 January The Almeida Theatre announces the full cast for its revival of Mike Bartlett’s Albion, directed by Rupert Goold, following the play’s acclaimed run in 2017. ALBION by Mike Bartlett Direction: Rupert Goold; Design: Miriam Buether; Light: Neil Austin Sound: Gregory Clarke; Movement Director: Rebecca Frecknall Monday 3 February – Saturday 29 February 2020 Press night: Wednesday 5 February 7pm ★★★★★ “The play that Britain needs right now” The Telegraph This is our little piece of the world, and we’re allowed to do with it, exactly as we like. Yes? In the ruins of a garden in rural England. In a house which was once a home. A woman searches for seeds of hope. Following a sell-out run in 2017, Albion returns to the Almeida for four weeks only. Joining the previously announced Victoria Hamilton (awarded Best Actress at 2018 Critics’ Circle Awards for this role) and reprising their roles are Nigel Betts, Edyta Budnik, Wil Coban, Margot Leicester, Nicholas Rowe and Helen Schlesinger. They will be joined by Angel Coulby, Daisy Edgar-Jones, Dónal Finn and Geoffrey Freshwater. Mike Bartlett’s plays for the Almeida include his adaptation of Maxim Gorky’s Vassa, Game and the multi-award winning King Charles III (Olivier Award for Best New Play) which premiered at the Almeida before West End and Broadway transfers, a UK and international tour. His television adaptation of the play was broadcast on BBC Two in 2017. Other plays include Snowflake (Old Fire Station and Kiln Theatre); Wild; An Intervention; Bull (won the Olivier Award for Outstanding Achievement in an Affiliate Theatre); an adaptation of Medea; Chariots of Fire; 13; Decade (co-writer); Earthquakes in London; Love, Love, Love; Cock (Olivier Award for Outstanding Achievement in an Affiliate Theatre); Contractions and My Child Artefacts. -

Student Auditions

Student Auditions Theater Emory • Fall 2014 Productions 2014-2015 - Global Perspectives: A Festival from Pinter to Rivera • Audition appointments on Saturday, August 30 start at 10:00AM • Callbacks the next day on Sunday, August 31. Hear more about auditions and the Theater Emory season at the General Meeting for all interested in Theater at Emory in the Munroe Theater in the Dobbs University Center at 5:30PM on Thursday, Aug. 28. Hear presentations by the Theater Studies Department and by the student theater organizations. Pinter Revue – by Harold Pinter, Directed by Donald McManus Sketch comedy in the British tradition, Pinter Revue is a collection of short works spanning more than thirty years of Pinter's career, from Trouble in the Works (1959) to New World Order (1991). Mountain Language (1988), a play about state terrorism, is described by Pinter as a "series of short, sharp images" exploring "suppression of language and the loss of freedom of expression." First Rehearsal- Sept. 9 Performances- Oct. 2 – 11 (fall break is Oct. 13-14) Time commitment: 3 weeks of segmented rehearsals, short script, and a 2-week run. (One performance at Emory’s Oxford campus.) A Pinter Kaleidoscope – By Harold Pinter, Directed by Brent Glenn An immersive confrontation with the comedic menace of Harold Pinter. The audience encounters Pinter’s dystopian nirvana by moving through various locations within the theater space. From his first play, The Room, to the totalitarian nightmare One for the Road, this devised theater event also features portions of The Birthday Party, The Hothouse, The Caretaker, and other plays, poems and speeches. -

Theatre Archive Project

THEATRE ARCHIVE PROJECT http://sounds.bl.uk Stephen Wischhusen – interview transcript Interviewer: Dominic Shellard 4 September 2006 Theatre worker. Donald Albery; audiences; The Boys in the Band; The Caretaker; The Intimate Theatre, Lyceum Theatre Crewe; Palmers Green; lighting; rep; Swansea theatre; theatre criticism; theatre going; theatre owners; tickets and reservations. DS: Can we start by talking about your first experience as a theatre goer with the theatre? SW: My first experiences will have been when I was between the ages of five and seven, and will have been taken by my parents many times. Firstly, I remember going to the Finsbury Park Empire as a birthday treat to see Barbara Kelly in the touring version of Peter Pan. DS: What year would this be? SW: It could have been, I suppose, 1954 - can’t quite remember how old I was, but certainly between ’52 and ’54, and through the fifties going to the theatre was a regular thing. Yes. We had a television, it was bought for me - I suppose as an incentive to recover from pneumonia, and sadly I did recover and they were 51 guineas down the shoot! But we didn’t watch it all the time. There was a choice to be made, it wasn’t on all the time, it was on or it was off, and Saturdays we used to go to Wood Green Empire. Mainly it was taking, I guess, number two tours or number three tours in those days, of West End successes, so we will have seen a play, such as Meet Mr Callaghan… Reluctant Heroes I remember. -

Monday 7 January 2019 FULL CASTING ANNOUNCED for THE

Monday 7 January 2019 FULL CASTING ANNOUNCED FOR THE WEST END TRANSFER OF HOME, I’M DARLING As rehearsals begin, casting is announced for the West End transfer of the National Theatre and Theatr Clwyd’s critically acclaimed co-production of Home, I’m Darling, a new play by Laura Wade, directed by Theatre Clwyd Artistic Director Tamara Harvey, featuring Katherine Parkinson, which begins performances at the Duke of York’s Theatre on 26 January. Katherine Parkinson (The IT Crowd, Humans) reprises her acclaimed role as Judy, in Laura Wade’s fizzing comedy about one woman’s quest to be the perfect 1950’s housewife. She is joined by Sara Gregory as Alex and Richard Harrington as Johnny (for the West End run, with tour casting for the role of Johnny to be announced), reprising the roles they played at Theatr Clwyd and the National Theatre in 2018. Charlie Allen, Susan Brown (Sylvia), Ellie Burrow, Siubhan Harrison (Fran), Jane MacFarlane and Hywel Morgan (Marcus) complete the cast. Home, I’m Darling will play at the Duke of York’s Theatre until 13 April 2019, with a press night on Tuesday 5 February. The production will then tour to the Theatre Royal Bath, and The Lowry, Salford, before returning to Theatr Clwyd following a sold out run in July 2018. Home, I’m Darling is co-produced in the West End and on tour with Fiery Angel. How happily married are the happily married? Every couple needs a little fantasy to keep their marriage sparkling. But behind the gingham curtains, things start to unravel, and being a domestic goddess is not as easy as it seems. -

Sexual Identity in Harold Pinter's Betrayal

Table of Contents Introduction: …………………………………………………………………………………..1 The Question of Identity in Harold Pinter’s Drama Chapter One:………………………………………………………………………………….26 Strong Arm Her: Gendered Identity in Harold Pinter’s A Kind of Alaska (1982) Chapter Two:…………………………………………………………………………………79 The Indelible Memory: Memorial Identity in Harold Pinter’s Ashes to Ashes (1996) Chapter Three:……………………………………………………………………………..129 Eroded Rhetoric: Linguistic Identity in Harold Pinter’s One for the Road (1984) and Mountain Language (1988) Chapter Four: ……………………………………………………………………………….188 Chic Dictatorship: Power and Political Identity in Harold Pinter’s Party Time (1991) Chapter Five:…………………………………………………………………………………240 The Ethic and Aesthetic of Existence: Sexual Identity in Harold Pinter’s Betrayal (1978) Chapter Six:…………………………………………………………………………………..294 Crumbling Families: Familial and Marital Identity in Harold Pinter’s Celebration (2000) Conclusion:……………………………………………………………………………………350 Bibliography:…………………………………………………………………………………359 I II Acknowledgment I would like to express my special thanks and appreciation to my principal supervisor Dr. Christian M. Billing, who has shown the attitude and the substance of a genius. He continually and persuasively conveyed a spirit of adventure in questioning everything and leaving no stone unturned. You have been a tremendous mentor for me. I would like to thank you for your incessant encouragement, support, invaluable advice, and patience without which the completion of this work would have been impossible. Thank you for allowing me to grow as a researcher. Your advice on both research as well as my career have been priceless. I would also like to thank Dr. K.S. Morgan McKean without which this work would not have been completed on time. A special thanks to my family. Words cannot express how grateful I’m to my sweet and loving parents Mandy Khaleel & Hasan Ali who did not spare the least effort to support me throughout my study. -

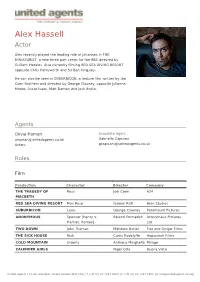

Alex Hassell Actor

Alex Hassell Actor Alex recently played the leading role of Johannes in THE MINIATURIST, a new three part series for the BBC directed by Guillem Morales. Also currently filming RED SEA DIVING RESORT opposite Chris Hemsworth and Sir Ben Kingsley. He can also be seen in SUBURBICON, a feature film written by the Coen Brothers and directed by George Clooney, opposite Julianne Moore, Oscar Isaac, Matt Damon and Josh Brolin. Agents Olivia Homan Associate Agent [email protected] Gabriella Capisani Actors [email protected] Roles Film Production Character Director Company THE TRAGEDY OF Ross Joel Coen A24 MACBETH RED SEA DIVING RESORT Max Rose Gideon Raff Bron Studios SUBURBICON Louis George Clooney Paramount Pictures ANONYMOUS Spencer [Henry V, Roland Emmerich Anonymous Pictures Hamlet, Romeo] Ltd TWO DOWN John Thomas Matthew Butler Fizz and Ginger Films THE SICK HOUSE Nick Curtis Radclyffe Hopscotch Films COLD MOUNTAIN Orderly Anthony Minghella Mirage CALENDER GIRLS Nigel Cole Buena Vista United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Television Production Character Director Company COWBOY BEPOP Vicious Alex Garcia Lopez Netflix THE MINATURIST Johannes Guillem Morales BBC SILENT WITNESS Simon Nick Renton BBC WAY TO GO Phillip Catherine Morshead BBC BIG THUNDER Abel White Rob Bowman ABC LIFE OF CRIME Gary Nash Jim Loach Loc Film Productions HUSTLE Viscount Manley John McKay BBC A COP IN PARIS Piet Nykvist Charlotte Sieling Atlantique Productions -

An Introduction to BETRAYAL

An Introduction to BETRAYAL There are times in the life of any individual or organization when they are challenged by events entirely beyond their control. One such event happened in the life of our Goodwill that challenged us to our very core. That event was the fraud committed by Carol Braun. We take pride in our corporate values and our integrity. We were exposed and vulnerable. The real mark of an organization's strength is its capacity to weather the most difficult storms. I believe that "Betrayal" is a testament to the strength and integrity of our Goodwill. It is a living testament to our capacity to learn from our hardships and mistakes. The book has found its way to every corner of America and has served to comfort and inform others who have faced similar circumstances. This book is dedicated to the men and women of Goodwill, our "People". We are stronger, more resilient and more compassionate as a result of this experience. We hope that Betrayal will, in some small way, ease any personal or professional challenges the reader may face and we stand ready to help. Bob Pedersen Chief Visionary & Storyteller Goodwill NCW BETRAYAL by Jed Block and the people of Goodwill Industries of North Central Wisconsin, Inc. © 2004 by Goodwill Industries of North Central Wisconsin, Inc., Menasha, Wisconsin 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword……………………………………………………………..Page 1 Chapters 1-30………………………………………………...……………..5 Epilogue…………………………………………………………………….74 Postscript……………………………………………………………………78 Appendix Mission, Vision, Values…………………………………………….81 Who’s Who -

Synesthetic Landscapes in Harold Pinter's Theatre

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2010 Synesthetic Landscapes in Harold Pinter’s Theatre: A Symbolist Legacy Graça Corrêa Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1645 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Synesthetic Landscapes in Harold Pinter’s Theatre: A Symbolist Legacy Graça Corrêa A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Theatre in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2010 ii © 2010 GRAÇA CORRÊA All Rights Reserved iii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Theatre in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ______________ ______________________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee Daniel Gerould ______________ ______________________________ Date Executive Officer Jean Graham-Jones Supervisory Committee ______________________________ Mary Ann Caws ______________________________ Daniel Gerould ______________________________ Jean Graham-Jones THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iv Abstract Synesthetic Landscapes in Harold Pinter’s Theatre: A Symbolist Legacy Graça Corrêa Adviser: Professor Daniel Gerould In the light of recent interdisciplinary critical approaches to landscape and space , and adopting phenomenological methods of sensory analysis, this dissertation explores interconnected or synesthetic sensory “scapes” in contemporary British playwright Harold Pinter’s theatre. By studying its dramatic landscapes and probing into their multi-sensory manifestations in line with Symbolist theory and aesthetics , I argue that Pinter’s theatre articulates an ecocritical stance and a micropolitical critique. -

BECKETT, SAMUEL, 1906-1989 Samuel Beckett Collection, 1955-1996

BECKETT, SAMUEL, 1906-1989 Samuel Beckett collection, 1955-1996 Emory University Robert W. Woodruff Library Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library Atlanta, GA 30322 404-727-6887 [email protected] Collection Stored Off-Site All or portions of this collection are housed off-site. Materials can still be requested but researchers should expect a delay of up to two business days for retrieval. Descriptive Summary Creator: Beckett, Samuel, 1906-1989 Title: Samuel Beckett collection, 1955-1996 Call Number: Manuscript Collection No. 902 Extent: .5 linear foot (1 box), 1 oversized papers folder (OP), and 1.56 MB born digital materials (63 files) Abstract: Collection of handbills, playbills, and programs relating to Samuel Beckett productions in the United Kingdom. Language: Materials entirely in English. Administrative Information Restrictions on access Collection stored off-site. Researchers must contact the Rose Library in advance to access this collection. Access to born digital materials is only available in the Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library. Terms Governing Use and Reproduction All requests subject to limitations noted in departmental policies on reproduction. Related Materials in Other Repositories Beckett collection, University of Reading, Reading, England; Carlton Lake collection of Samuel Beckett papers and Samuel Beckett collection, Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, Emory Libraries provides copies of its finding aids for use only in research and private study. Copies supplied may not be copied for others or otherwise distributed without prior consent of the holding repository. Samuel Beckett collection, 1955-1996 Manuscript Collection No. 902 University of Texas at Austin; and Samuel Beckett papers, Washington University Libraries, Department of Special Collections. -

Custodians for Covid, Theatres Press Release

Oxford-based photographer Joanna Vestey and collaborator Tara Rowse have set up a bold fundraising initiative, Custodians for Covid, to raise funds for threatened arts institutions. Its first edition focuses on raising money for theatres currently in crisis due to the Covid-imposed lockdown. This includes world renowned theatres such as the National Theatre, the Roundhouse and the Young Vic. (L) Deborah McGhee, Head of Building Operations, The Globe. London, June 2020 © Joanna Vestey (R) Charlie Jones, Building Services Manager, The Royal Albert Hall. London, June 2020 © Joanna Vestey Vestey has produced a collection of 20 photographs, each featuring an affected London theatre, portraying the custodian who is charged with its care during this time of crisis. The photographs are being sold in limited editions to raise funds for each theatre. The target is to raise £1million in charitable donations for the 20 London theatres, amounting to £50,000 per theatre. Each image in the series features an iconic theatre space in which Vestey has highlighted a custodian. The custodian’s presence brings the setting to life and celebrates the often-unknown role of the guardians who continue to maintain these institutions. The series explores themes such as heritage, stewardship, identity and preservation, which feel even more poignant given the isolation so many are currently experiencing and the uncertainties so many face. The images are for sale through Joanna Vestey's website and build on her widely acclaimed series custodians, the first of which focused on the hallowed institutions of Oxford, together with the custodians responsible for them. The series was exhibited at the Venice Biennale, Oxford Biennale as well as published by and exhibited at The Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.