Harold Pinter: from Poetics to Politics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Strategies of Political Theatre Post-War British Playwrights

Strategies of Political Theatre Post-War British Playwrights Michael Patterson published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building,Trumpington Street,Cambridge cb2 1rp,United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building,Cambridge, cb2 2ru,UK 40 West 20th Street,New York, ny 10011–4211,USA 477 Williamstown Road,Port Melbourne, vic 3207,Australia Ruiz de Alarcon´ 13, 28014 Madrid,Spain Dock House,The Waterfront,Cape Town 8001,South Africa http://www.cambridge.org C Cambridge University Press 2003 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2003 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press,Cambridge Typefaces Trump Mediaeval 9.25/14 pt. and Schadow BT System LATEX 2ε [tb] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library isbn 0 521 25855 3 hardback Contents Acknowledgments ix Brief chronology, 1953–1989 x Introduction 1 Part 1: Theory 1 Strategies of political theatre: a theoretical overview 11 Part 2: Two model strategies 2 The ‘reflectionist’ strategy: ‘kitchen sink’ realism in Arnold Wesker’s Roots (1959) 27 3 The ‘interventionist’ strategy: poetic politics in John Arden’s Serjeant Musgrave’s Dance (1959) 44 Part 3: The reflectionist strain 4 The dialectics of comedy: Trevor Griffiths’s Comedians (1975) 65 5 Appropriating middle-class comedy: Howard Barker’s Stripwell -

Harold Pinter's Bleak Political Vision

http://dx.doi.org/10.18778/7525-994-0.07 Studies in English Drama and Poetry Vol. 3 Paulina Mirowska University of Łódź The Silencing of Dissent: Harold Pinter’s Bleak Political Vision Abstract: The article centres upon one of Harold Pinter’s last plays, Celebration, first performed at the Almeida Theatre, London, on 16 March 2000. Similarly to Party Time, a dystopian political play written almost a decade earlier, Celebration pursues the theme of a sheltered zone of power effectively marginalising a social “other.” This time, however, Pinter adopts the mode of comedy to dramatise the fragile and circumscribed existence of dissent and the moral coarseness of complacent elites. The article traces a number of intriguing analogies between Celebration and Pinter’s explicitly political plays of the 1980s and 1990s dealing with the suppression of dissident voices by overwhelming structures of established power. It is demonstrated how – despite the play’s fashionable restaurant setting, ostensibly far removed from the torture sites of One for the Road, Mountain Language and The New World Order – Pinter succeeds in relating the insulated world of Celebration to the harsh reality of global oppression. What is significant, I argue here against interpreting the humorous power inversions of the social behaviour in Celebration as denoting any fundamental changes in larger sociopolitical structures. It is rather suggested that the play reveals the centrality of Pinter’s scepticism about the possibility of eluding, subverting or curtailing the silencing force of entrenched status quo, implying perpetual nature of contemporary inequities of power. I also look at how the representatives of the empowered in-group in the play contain transgressing voices and resort to language distortion to vindicate oppression. -

Trademark Rights for Signature Touchdown Dances

Trademark Rights for Signature Touchdown Dances Abstract Famous athletes are increasingly cultivating signature dances and celebratory moves, such as touchdown dances, as valuable and commercially viable elements of their personal brands. As these personal branding devices have become immediately recognizable and have begun being commercially exploited, athletes need to legally protect their signature dances. This paper argues that trademark law should protect the signature dances and moves of famous athletes, particularly the signature touchdown dances of NFL players. Because touchdown dances are devices capable of distinguishing one player from another, are non- functional, and are commercially used in NFL games, the dances should be registrable with the USPTO as trademarks for football services. Trademark Rights for Signature Touchdown Dances Joshua A. Crawford Table of Contents I. Introduction . 1 A. Aaron Rodgers and the “Discount Double Check” . 1 B. Signature Dances and Moves in Sports . 4 C. Trademark Protection for Signature Sports Dances . 8 II. Trademark Eligibility and Registration for Signature Touchdown Dances . 10 A. Background Principles of American Trademark Law . 11 B. Subject-Matter Eligibility. 12 C. Distinctiveness . 15 1. Distinctiveness Background . .. 15 2. Acquired Distinctiveness for Dances with Secondary Meaning . 18 3. The Possibility of Proving Inherent Distinctiveness under Seabrook . 19 4. The Possibility of Wal-Mart Barring Inherent Distinctiveness . 20 D. Functionality . 21 E. Use in Commerce . 24 1. Interstate Commerce . 24 2. Bona Fide Commercial Use . 25 a. Manner of Use . 26 b. Publicity of Use . 28 c. Frequency of Use . 31 III. Infringement . 33 A. Real-World Unauthorized Copying of Dances among Players—Permissible Parody . 34 B. -

Why We Play: an Anthropological Study (Enlarged Edition)

ROBERTE HAMAYON WHY WE PLAY An Anthropological Study translated by damien simon foreword by michael puett ON KINGS DAVID GRAEBER & MARSHALL SAHLINS WHY WE PLAY Hau BOOKS Executive Editor Giovanni da Col Managing Editor Sean M. Dowdy Editorial Board Anne-Christine Taylor Carlos Fausto Danilyn Rutherford Ilana Gershon Jason Troop Joel Robbins Jonathan Parry Michael Lempert Stephan Palmié www.haubooks.com WHY WE PLAY AN ANTHROPOLOGICAL STUDY Roberte Hamayon Enlarged Edition Translated by Damien Simon Foreword by Michael Puett Hau Books Chicago English Translation © 2016 Hau Books and Roberte Hamayon Original French Edition, Jouer: Une Étude Anthropologique, © 2012 Éditions La Découverte Cover Image: Detail of M. C. Escher’s (1898–1972), “Te Encounter,” © May 1944, 13 7/16 x 18 5/16 in. (34.1 x 46.5 cm) sheet: 16 x 21 7/8 in. (40.6 x 55.6 cm), Lithograph. Cover and layout design: Sheehan Moore Typesetting: Prepress Plus (www.prepressplus.in) ISBN: 978-0-9861325-6-8 LCCN: 2016902726 Hau Books Chicago Distribution Center 11030 S. Langley Chicago, IL 60628 www.haubooks.com Hau Books is marketed and distributed by Te University of Chicago Press. www.press.uchicago.edu Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper. Table of Contents Acknowledgments xiii Foreword: “In praise of play” by Michael Puett xv Introduction: “Playing”: A bundle of paradoxes 1 Chronicle of evidence 2 Outline of my approach 6 PART I: FROM GAMES TO PLAY 1. Can play be an object of research? 13 Contemporary anthropology’s curious lack of interest 15 Upstream and downstream 18 Transversal notions 18 First axis: Sport as a regulated activity 18 Second axis: Ritual as an interactional structure 20 Toward cognitive studies 23 From child psychology as a cognitive structure 24 . -

Chapter One a Theoretical Background to the Figure of The

19 Chapter One A Theoretical Background to the figure of the Artist in Literature and Theatre In an article published in Fall 2009, Csilla Bertha maintains that the central place an artist occupies within a work of art adds an additional dimension to plays, since the fictional artist’s point of view, attitudes to the world and evaluation of phenomena, may double or multiply the layers of the connections between art and life. She then adds: If an artist is chosen to be the protagonist of a play or novel, that choice naturally leads to the thematization of questions and dilemmas about the existence of art and the artist; relations between art and life, art/artist and the world; the nature of artistic creation; differences between ways of life, values, and views of ordinary people and artists; relations between individual and community, between the subject and objective reality; and many other similar issues.1 No doubt, with the advent of highly sophisticated and challenging notions such as Formalism2 and the death of the author,3 it is hard to conceive the figure of the artist without paying attention to the interrelations between art and life in which the ideal and reality, subject and object, constitute sharp contrasts. Traditionally, this dialectical relationship forms “binary 1 Csilla Bertha, “Visual Art and Artist in Contemporary Irish Drama”, Hungarian Journal of English and American Studies (HJEAS) v. 15, no. 2 (Fall 2009): 347. 2 Formalism is a Russian literary movement which originated in the second decade of the twentieth century. Its leading figures were both linguists and literary historians such as Boris Eikhenbaum (1886-1959), Roman Jakobson (1895-1982), Viktor Shklovsky (1893-1984), Boris Tomashevskij (1890-1957) and Jurij Tynjanov (1894-1943). -

Family Comes First Breaks Down What Families Want Into Five Specific Features Representing a Transformed Justice System

Comes ly Fi mi r a st F A Workbook to Transform the Justice System by Partnering With Families tice & T e h Jus Alli out anc r Y e F fo o n r Y g The Campaign for Youth Justice i ou a (CFYJ) is a national nonprofit organization t p working to end the practice of trying, sentencing, h m a and incarcerating youth in the adult criminal justice system. Ju Part of our work involves improving the juvenile justice system and s C t i e ensuring that youth and families have a voice in justice system reform c efforts. Through these efforts we have seen and heard first-hand the trouble e T that families face when dealing with the justice system and were approached by the Annie E. Casey Foundation to write this publication. CFYJ was started in 2005 by a family member whose child was being prosecuted in the adult system. Since our founding, we have placed a significant emphasis on making sure that youth and families who have been directly affected by the justice system are involved in our advocacy efforts. Becoming more family-focused means that everyone, including advocacy organizations such as ours, need to start working differently. We are responsive to families by making a concerted effort to meet the needs of families who call our offices looking for help, and we involve family members in discussions around our strategic goals and initiatives. One of the major components of our work is staffing and supporting the Alliance for Youth Justice, formerly known as the National Parent Caucus. -

Trends in Political Television Fiction in the UK: Themes, Characters and Narratives, 1965-2009

This item was submitted to Loughborough’s Institutional Repository (https://dspace.lboro.ac.uk/) by the author and is made available under the following Creative Commons Licence conditions. For the full text of this licence, please go to: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5/ Trends in political television fiction in the UK: Themes, characters and narratives, 1965-2009. 1 Introduction British television has a long tradition of broadcasting ‘political fiction’ if this is understood as telling stories about politicians in the form of drama, thrillers and comedies. Vote, Vote for Nigel Barton (1965) is generally considered the first of these productions for a mass audience presented in the then usual format of the single television play. Ever since there has been a regular stream of such TV series and TV-movies, varying in success and audience appeal, including massive hits and considerable failures. Television fiction has thus become one of the arenas of political imagination, together with literature, art and - to a lesser extent -music. Yet, while literature and the arts have regularly been discussed and analyzed as relevant to politics (e.g. Harvie, 1991; Horton and Baumeister, 1996), political television fiction in the UK has only recently become subject to academic scrutiny, leaving many questions as to its meanings and relevance still to be systematically addressed. In this article we present an historical and generic analysis in order to produce a benchmark for this emerging field, and for comparison with other national traditions in political TV-fiction. We first elaborate the question why the study of the subject is important, what is already known about its themes, characters and narratives, and its capacity to evoke particular kinds of political engagement or disengagement. -

A Study of the Royal Court Young Peoples’ Theatre and Its Development Into the Young Writers’ Programme

Building the Engine Room: A Study of the Royal Court Young Peoples’ Theatre and its Development into the Young Writers’ Programme N O Holden Doctor of Philosophy 2018 Building the Engine Room: A Study of the Royal Court’s Young Peoples’ Theatre and its Development into the Young Writers’ Programme Nicholas Oliver Holden, MA, AKC A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Lincoln for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Fine and Performing Arts College of Arts March 2018 2 DECLARATION I declare that this thesis is my own work and has not been submitted in substantially the same form for a higher degree elsewhere. 3 Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank my supervisors: Dr Jacqueline Bolton and Dr James Hudson, who have been there with advice even before this PhD began. I am forever grateful for your support, feedback, knowledge and guidance not just as my PhD supervisors, but as colleagues and, now, friends. Heartfelt thanks to my Director of Studies, Professor Mark O’Thomas, who has been a constant source of support and encouragement from my years as an undergraduate student to now as an early career academic. To Professor Dominic Symonds, who took on the role of my Director of Studies in the final year; thank you for being so generous with your thoughts and extensive knowledge, and for helping to bring new perspectives to my work. My gratitude also to the University of Lincoln and the School of Fine and Performing Arts for their generous studentship, without which this PhD would not have been possible. -

Sample Chapter

Copyrighted material – 9781137590794 Copyrighted material – 9781137610270 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Some Key Terms and Ideas viii The introduction offers the reader some definitions of key terms and theo- ries, as well as seeking to explore what might be meant by ‘contemporary’. It also explains the importance of analysing critical and scholarly commen- tary, introduces some of the plays explored later in the book and provides an outline of the structure of the volume. CHAPTER ONE The Rise of Political Theatre 1 The book starts by analysing the rise of left-wing socialist theatre in the late 1960s to the early 1980s, exploring the relevance of these key dates and examining the theatrical and political landscape at this time. The chapter explores the work of Bond, Hare and Brenton, and then Pinter, analysing the critical response to their work in first performance, as well as some relevant modern revivals, and also offers commentary on the relationship between ‘real’ politics and theatrical response to them. CHAPTER TWO The Gendering of Political Theatre: Women’s Writing and Feminist Drama 25 Following on from analysis of political playwriting in chapter one, this chapter examines the rise of feminist theatre in the 1970s and 1980s. Focusing on Daniels and Churchill, the chapter analyses the meaning and definition of feminist theatre, and seeks to locate these dramatists’ work in the context of feminist socialist writing more widely. The chapter explores the often hostile critical reaction to this work, and reflects on feminist theatre’s attempts to restructure dominant forms of theatre into more fluid and deconstructed structures. v Copyrighted material – 9781137610270 Copyrighted material – 9781137610270 vi CONTENTS CHAPTER THREE In-Yer-Face Theatre: The Shocking New Face of Political Drama? 48 In the 1990s, a ‘new’ and shocking form of theatre appeared to erupt on the British stage – so-called ‘In-Yer-Face’ theatre. -

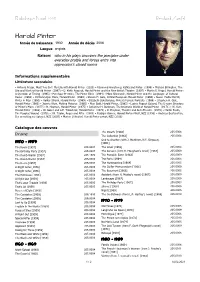

Harold Pinter

Bibliothèque Nobel 2005 Bernhard Zweifel Harold Pinter Année de naissance 1930 Année du décès 2008 Langue anglais Raison: who in his plays uncovers the precipice under everyday prattle and forces entry into oppression's closed rooms Informations supplementaire Littérature secondaire • Antonia Fraser, Must You Go?: My Life with Harold Pinter (2010) • Raymond Armstrong, Kafka and Pinter (1999) • Michael Bi llington, The Life and Work of Harold Pinter (1997) • D. Keith Peacock, Harold Pinter and the New British Theatre (1997) • Martin S. Rega l, Harold Pinter: A Question of Timing (1995) • Penelope Prentice, The Pinter Ethic (1994) • Marc Silverstein, Harold Pinter and the Language of Cultural Power (1993) • Chittanranjan Misra, Harold Pinter (1993) • Steven H. Gale, Critical Essays on Harold Pinter (1990) • Susan Hollis Merritt, Pinter in Play (1990) • Volker Strunk, Harold Pinter (1989) • Elizabeth Sakellaridou, Pinter's Female Portraits (1988) • S tephen H. Gale, Harold Pinter (1986) • Joanne Klein, Making Pictures (1985) • Alan Bold, Harold Pinter, (1985) • Lucina Paquet Gabard, The D ream Structure of Pinter's Plays (1977) • R. Hayman, Harold Pinter (1975) • Jatherine H. Burkman, The Dramatic World of Harold Pinter (19 71) • W. Kerr, Harold Pinter (1968) • W. Baker and S.E. Tabachnik, Harold Pinter (1973) • R. Hayman, Theatre and Anti -Theatre (1979) • Martin Esslin, The Peopled Wound (1970) • J.R. Taylor, Anger and After (1969) • R üdiger Görner, Harold Pinters Welt, NZZ (1998) • Andreas Breitenstein, Der zerschlagene Spiegel, NZZ (2005) • Marion Löhndorf, Harold Pinter privat, NZZ (2010) Catalogue des oeuvres The Dwarfs [1960] 205.0008 Drame The Collection [1961] 205.0004 One to Another (with J. -

Theatre, Communism, and Love

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE PASSIONATE AMATEURS Passionate Amateurs THEATRE, COMMUNISM, AND LOVE Nicholas Ridout THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN PRESS Ann Arbor Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2013 All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written per- mission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid-free paper 2016 2015 2014 2013 4 3 2 1 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging-in- Publication Data Ridout, Nicholas Peter. Passionate amateurs : theatre, communism, and love / Nicholas Ridout. pages cm. — (Theater—theory/text/performance) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0- 472- 11907- 3 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0- 472- 02959- 4 (e- book) 1. Theater and society. 2. Communism and culture. I. Title. PN2051.R53 2013 792—dc23 2013015596 For Isabel and Peter, my parents Acknowledgments Throughout the writing of this book I was fortunate to work in the De- partment of Drama at Queen Mary University of London. Colleagues and students alike made the department a truly stimulating and supportive place to be, to work, and to think. I am grateful to them all. I owe particu- lar thanks, for conversations that contributed in tangible ways to the de- velopment of this work, to Bridget Escolme, Jen Harvie, Michael McKin- nie, Lois Weaver, and Martin Welton. -

Writing Figures of Political Resistance for the British Stage Vol1.Pdf

Writing Figures of Political Resistance for the British Stage Volume One (of Two) Matthew John Midgley PhD University of York Theatre, Film and Television September 2015 Writing Figures of Resistance for the British Stage Abstract This thesis explores the process of writing figures of political resistance for the British stage prior to and during the neoliberal era (1980 to the present). The work of established political playwrights is examined in relation to the socio-political context in which it was produced, providing insights into the challenges playwrights have faced in creating characters who effectively resist the status quo. These challenges are contextualised by Britain’s imperial history and the UK’s ongoing participation in newer forms of imperialism, the pressures of neoliberalism on the arts, and widespread political disengagement. These insights inform reflexive analysis of my own playwriting. Chapter One provides an account of the changing strategies and dramaturgy of oppositional playwriting from 1956 to the present, considering the strengths of different approaches to creating figures of political resistance and my response to them. Three models of resistance are considered in Chapter Two: that of the individual, the collective, and documentary resistance. Each model provides a framework through which to analyse figures of resistance in plays and evaluate the strategies of established playwrights in negotiating creative challenges. These models are developed through subsequent chapters focussed upon the subjects tackled in my plays. Chapter Three looks at climate change and plays responding to it in reflecting upon my creative process in The Ends. Chapter Four explores resistance to the Iraq War, my own military experience and the challenge of writing autobiographically.