Trends in Political Television Fiction in the UK: Themes, Characters and Narratives, 1965-2009

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(TU Dresden) Does the Body Politic Have No Genitals?

Accepted manuscript version of: Schwanebeck, Wieland. “Does the Body Politic Have No Genitals? The Thick of It and the Phallic Nature of the Political Arena.” Contemporary Masculinities in the UK and the US: Between Bodies and Systems, edited by Stefan Horlacher and Kevin Floyd, Palgrave Macmillan, 2017, pp. 75–98, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-50820-7. Wieland Schwanebeck (TU Dresden) Does the Body Politic Have No Genitals? The Thick of It and the Phallic Nature of the Political Arena Though it may not have required drastic proof, recent news from the political arena suggests that certain distinguished statesmen tend to rely on a candid exhibition of genitals in order to draw attention to their virility and, by implication, to their political power. Silvio Berlusconi made the headlines in 2010, when he insisted that the missing penis of a Mars statue be restored before the sculpture was deemed suitable to adorn his office as Italian Prime Minister, horrified reactions amongst art historians notwithstanding (cf. Williams). This anecdote sits comfortably amongst other tales from the bunga bunga crypt, yet one may as well wonder whether Berlusconi is not just a tad less inhibited than some of his colleagues when it comes to acknowledging that the body politic requires visible proofs of manhood. Slavoj Žižek has characterized the contemporary media environment as one in which it would not appear out of the question for a politician to “allow a hard-core video of his or her sexual shenanigans to circulate in public, to convince the voters of his or her force of attraction or potency” (208). -

Harold Pinter's Bleak Political Vision

http://dx.doi.org/10.18778/7525-994-0.07 Studies in English Drama and Poetry Vol. 3 Paulina Mirowska University of Łódź The Silencing of Dissent: Harold Pinter’s Bleak Political Vision Abstract: The article centres upon one of Harold Pinter’s last plays, Celebration, first performed at the Almeida Theatre, London, on 16 March 2000. Similarly to Party Time, a dystopian political play written almost a decade earlier, Celebration pursues the theme of a sheltered zone of power effectively marginalising a social “other.” This time, however, Pinter adopts the mode of comedy to dramatise the fragile and circumscribed existence of dissent and the moral coarseness of complacent elites. The article traces a number of intriguing analogies between Celebration and Pinter’s explicitly political plays of the 1980s and 1990s dealing with the suppression of dissident voices by overwhelming structures of established power. It is demonstrated how – despite the play’s fashionable restaurant setting, ostensibly far removed from the torture sites of One for the Road, Mountain Language and The New World Order – Pinter succeeds in relating the insulated world of Celebration to the harsh reality of global oppression. What is significant, I argue here against interpreting the humorous power inversions of the social behaviour in Celebration as denoting any fundamental changes in larger sociopolitical structures. It is rather suggested that the play reveals the centrality of Pinter’s scepticism about the possibility of eluding, subverting or curtailing the silencing force of entrenched status quo, implying perpetual nature of contemporary inequities of power. I also look at how the representatives of the empowered in-group in the play contain transgressing voices and resort to language distortion to vindicate oppression. -

GET BETTER FASTER: the Ultimate Guide to the Practice of Retrospectives

GET BETTER FASTER: The Ultimate Guide to the Practice of Retrospectives www.openviewlabs.com INTRODUCTION n 1945, the managers of a tiny car manufacturer in Japan took I It can cause the leadership team to be trapped inside a “feel-good stock of their situation and discovered that the giant firms of the bubble” where bad news is avoided or glossed over and tough U.S. auto industry were eight times more productive than their issues are not directly tackled. This can lead to an evaporating firm. They realized that they would never catch up unless they runway; what was assumed to be a lengthy expansion period can improved their productivity ten-fold. rapidly contract as unexpected problems cause the venture to run out of cash and time. Impossible as this goal seemed, the managers set out on a path of continuous improvement that 60 years later had transformed When done right, the retrospective review can be a powerful their tiny company into the largest automaker in the world and antidote to counteract these tendencies. driven the giants of Detroit to the very brink of bankruptcy. In that firm—Toyota—the commitment to continuous improve- This short handbook breaks down the key components of the ment is still a religion: over a million suggestions for improvement retrospective review. Inside you will learn why it is important, are received from their employees and dealt with each year. find details on how to go about it, and discover the pitfalls and difficulties that lie in the way of conducting retrospectives The key practice in the religion of continuous improvement is successfully. -

Guardian and Observer Editorial

Monday 01.01.07 Monday The year that changed our lives Swinging with Tony and Cherie Are you a malingerer? Television and radio 12A Shortcuts G2 01.01.07 The world may be coming to an end, but it’s not all bad news . The question First Person Are you really special he news just before Army has opened prospects of a too sick to work? The events that made Christmas that the settlement of a war that has 2006 unforgettable for . end of the world is caused more than 2 million people nigh was not, on the in the north of the country to fl ee. Or — and try to be honest here 4 Carl Carter, who met a surface, an edify- — have you just got “party fl u”? ing way to conclude the year. • Exploitative forms of labour are According to the Institute of Pay- wonderful woman, just Admittedly, we’ve got 5bn years under attack: former camel jockeys roll Professionals, whose mem- before she flew to the before the sun fi rst explodes in the United Arab Emirates are to bers have to calculate employees’ Are the Gibbs watching? . other side of the world and then implodes, sucking the be compensated to the tune of sick pay, December 27 — the fi rst a new year’s kiss for Cherie earth into oblivion, but new year $9m, and Calcutta has banned day back at work after Christmas 7 Karina Kelly, 5,000,002,007 promises to be rickshaw pullers. That just leaves — and January 2 are the top days 16 and pregnant bleak. -

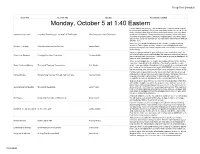

Download Deep Dive Schedule

Deep Dive Schedule Track Title Session Title Speaker Session Description Monday, October 5 at 1:40 Eastern "As the Father has sent me, I am sending you." How can you get out of the box of your building? Go to your community and meet a need. Create family fun days. Host special events and attract those in your city. Have Community Outreach Creatively Reaching Out: Go And Tell The People Miss PattyCake (Jean Thomason) a concert/movie/picnic. Reach into homes via media. Partner with other churches for greater impact. Become a brighter light in your area. Make and execute a plan for outreach so you can share God's big love with big and little lives. Have you ever wondered what goes into effective, creative teaching sessions? Take a journey inside Justyn's successful playbook as he Creative Teaching A Creative Process You Can Use Justyn Smith shares how anyone can create a system and environment of creativity in their ministry. Have you always wanted to give writing your own curriculum a try? Are you tired of using up your entire budget on expensive curriculum that you Curriculum Blueprint Creating Your Own Curriculum Corinne Noble have to heavily edit every week? Find out how to go from a blank page of paper to a full curriculum series. There is nothing quite like seeing the joy in a preschooler's face as they experience something for the first time. The joy of seeing them learn Early Childhood Ministry The Joy Of Teaching Preschoolers B.A. Snider about Jesus and laying a foundation for their growth in a relationship with the Creator of the universe is, in a word, AWESOME! Join me for some tips on teaching your young ones in this crazy, yet joyous, season of life. -

Little Reason to Smile As Iannucci Lays Bare the Tension Between BBC and Tories

Little reason to smile as Iannucci lays bare the tension between BBC and... https://theconversation.com/little-reason-to-smile-as-iannucci-lays-bare-t... Academic rigour, journalistic flair Little reason to smile as Iannucci lays bare the tension between BBC and Tories August 27, 2015 3.54pm BST Author James Blake Director, Centre for Media and Culture, Edinburgh Napier University ‘Are you listening, John Whittingdale?“ Danny Lawson/PA We are all in this together. That, according to Armando Iannucci, was the theme of his MacTaggart lecture at the Edinburgh International Television Festival. It was his rallying cry to a hall packed with TV executives, directors, commissioning editors, producers and – yes – politicians. It was a speech aimed at unifying the UK TV industry behind a single goal: to save the BBC from the politicians. Said Iannucci: We have changed international viewing for the better, but sometimes our political partners forget this. When Zai Bennett, director of Sky Atlantic, introduced the Glasgow-born creator of The Thick of It, I’m Alan Partridge and Veep, he said that the MacTaggart lecture “sets the tone for the TV festival”. In truth the tone had been set long before that moment. John Whittingdale, the UK culture secretary, 1 of 4 30/07/2019, 11:15 Little reason to smile as Iannucci lays bare the tension between BBC and... https://theconversation.com/little-reason-to-smile-as-iannucci-lays-bare-t... had done a question-and-answer session earlier in the afternoon, while the future of the BBC was bubbling just under the surface during almost every debate in the day. -

Oxford Lecture 1 - Final Master

OXFORD LECTURE 1 - FINAL MASTER HOW TO GROW A CREATIVE BUSINESS BY ACCIDENT The legendarily bullish film director Alan Parker once adapted Shaw's famous dictum about the academic profession - "those who can, do. Those who can't teach." So far so familiar. And to many in this room, no doubt, so annoying. But he went on: "those who can't teach, teach gym. And those who can't teach gym, teach at film school." I appreciate that Oxford is not a film school, though it has a more distinguished record than any film school for supplying the talent that has fuelled the British film and TV industries for almost a century - on and off camera. Writers like Richard Curtis, who brought us 4 Weddings and a Funeral, Love Actually, The Vicar of Dibley and Blackadder; or The Full Monty and Slumdog Millionaire scribe Simon Beaufoy; directors of the diversity of Looking for Eric's Ken Loach and 24 Hour Party People's Michael Winterbottom; writer/directors like Monty Python's Terry Jones and the Thick of It's Armando Iannucci; actors and performers ranging from Hugh Grant to Rowan Atkinson; and broadcasting luminaries like the BBC's Director General Mark Thompson and News International's very own Rupert Murdoch. So, Oxford has been a pretty efficient film and TV school, without even trying. And perhaps that is Parker's point. Can what passes for creativity in film and TV ever really be taught? But here in my capacity as News International Visiting Professor of Broadcast Media (or if you prefer an acronym, NIVPOB - the final M is silent) I may be even further down Parker's food chain. -

The New Age Under Orage

THE NEW AGE UNDER ORAGE CHAPTERS IN ENGLISH CULTURAL HISTORY by WALLACE MARTIN MANCHESTER UNIVERSITY PRESS BARNES & NOBLE, INC., NEW YORK Frontispiece A. R. ORAGE © 1967 Wallace Martin All rights reserved MANCHESTER UNIVERSITY PRESS 316-324 Oxford Road, Manchester 13, England U.S.A. BARNES & NOBLE, INC. 105 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10003 Printed in Great Britain by Butler & Tanner Ltd, Frome and London This digital edition has been produced by the Modernist Journals Project with the permission of Wallace T. Martin, granted on 28 July 1999. Users may download and reproduce any of these pages, provided that proper credit is given the author and the Project. FOR MY PARENTS CONTENTS PART ONE. ORIGINS Page I. Introduction: The New Age and its Contemporaries 1 II. The Purchase of The New Age 17 III. Orage’s Editorial Methods 32 PART TWO. ‘THE NEW AGE’, 1908-1910: LITERARY REALISM AND THE SOCIAL REVOLUTION IV. The ‘New Drama’ 61 V. The Realistic Novel 81 VI. The Rejection of Realism 108 PART THREE. 1911-1914: NEW DIRECTIONS VII. Contributors and Contents 120 VIII. The Cultural Awakening 128 IX. The Origins of Imagism 145 X. Other Movements 182 PART FOUR. 1915-1918: THE SEARCH FOR VALUES XI. Guild Socialism 193 XII. A Conservative Philosophy 212 XIII. Orage’s Literary Criticism 235 PART FIVE. 1919-1922: SOCIAL CREDIT AND MYSTICISM XIV. The Economic Crisis 266 XV. Orage’s Religious Quest 284 Appendix: Contributors to The New Age 295 Index 297 vii LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS A. R. Orage Frontispiece 1 * Tom Titt: Mr G. Bernard Shaw 25 2 * Tom Titt: Mr G. -

Wordsearch - Q Christmas TV Specials a Seek out the TV Seasonal Offerings in the Grid

Wordsearch - q Christmas TV specials a Seek out the TV seasonal offerings in the grid. Words go up down, diagonally – and forwards and backwards T P B N D S S G I B S L Q U A L E Q L N E M S S R A G D R I D M H T N L S G O T L C M G D E H L U E R A E D C N W B B S O M K C J J H C T L P U X O V U O S H U L L N Q A A J R N E A V E E T V O M M E C G I A W H G D Z X W I M G O D M H Q R T C U E F I A I D W I P B I T T Z A W A T A P T A V B G O S W Q B H D K L J O J B J G I H Y K R T S W I H S H C D E W Y t S H H E O S E E T S G C H E F A B I R D I N T H E H A N D O F T S W T D C T P D E Y A O S T R E A L R E R H H I Y Q H S Z Q U S U F I Q T N C L F P W R H A O I O E Y J Y P B N N S U P E D X R S S F M E R T G B A Z N Z H F W F Z D R K W L X E E M O T O P R M O S X M K A N I Z C U M E T I L O D H R D B L T U G U K B Y G I K S X S E W T F U G S E L I S Y E E M N G Z J D S B V W R I R E C A W B L J L C E S C F Y K C H K A E S U B F S V Z S A O R G T O R J K G K T D E E P E F A T P T O D C D G U J Z G O S X N D E I S Y O A E T O M O R D S O E R U I S S B I N E E S S D E R U Z A K K R W G Q S R J D U K R C L N M S H M T V Y I I j L P C Q N K G P I N E K A C G D I E V I H J G D Z J A M G T T C H H L O T A E E S L C R R L S F Z R R O V T N N L O C H N O U T Z Y N J F Z M S Z P C Y H C R I S S H O N I K H T H A H M B W E M I M J M E U F E R I N Q S G Q K K V C M Z Y J F R E I S A I O F B R F R R C B P A P G G V D C P E E R Y M I I D K A I Z Y H B Y Q M R T R I H S E E R H F E H L I A A D S F M J A M H C E Y M N L N Y N S D E Y N J I X L A V F K E -

PO BOX 11 Informs Readers of News, Summer 2011 PO BOX 11 Events and People Who Enhance Recovery

alumni news & views PO BOX 11 informs readers of news, SUMMER 2011 PO BOX 11 events and people who enhance recovery. At home and at work Alum finds inspiration through service At age 33, Ben B. became a stay-at-home dad. Before he knew it, his alcohol consumption escalated, turning him into the dad he never wanted to be. Too drunk to take his three-year-old daughter to swimming lessons, he’d trek with her instead to the liquor store or plop her in front of the television for hours. And there were times when he picked her up from play dates with alcohol on his breath. He knew, deep down, he needed help. He called Hazelden. “I was honest about my drinking for the first time. Something happens when you’re honest,” recalls Ben. “I remember telling the counselor I’d do anything he said—I’d wear red clown shoes and jump up and down if I could take a shower in the morning without, halfway through, wondering what I was going to drink and how I was going to hide it.” “Treatment allowed me to draw a line in the sand—to say, ‘From this point forward, things are going to be different.’” Now, at age 38, Ben takes life one day at a time—without alcohol or other drugs—grateful to a be part of his young family in a way he never could when beer and gin comprised his priority list. “I’m learning to be present for my family,” says Ben. “I finally understand what that means, and it’s something I strive to do every day: Be home for dinner, cook dinner, serve them, pick up the house and set an example for my kids.” His enthusiastic and lasting sobriety landed Ben a job coordinating recovery services for young adults who either attend or want to attend the College of St. -

1 Rosie & George 32 T2 the Lads 27 T2 Beige Food Brigade 27

Team’s Table Position Team Name Current Points 1 Rosie & George 32 T2 The Lads 27 T2 Beige Food Brigade 27 T2 Things Can Tony Get Better 27 T2 wellbeck wellies 27 T2 Ozymandias United 27 T2 StevieB 27 T2 Holbrook's Cabinet 27 T2 The A-Team 27 T2 #longtermeconomicplan 27 T2 Team "Gareth" 27 12 A Yacht Called Nellie 24 13 This Does Not Slip 22 14 Russell's Rebels 21 T15 Real Politik 20 T15 On the fringe 20 T15 Scotland's Imperial Masters 20 T15 Black Beauty - now there's a dark horse 20 T15 Ministry of Spin 20 T15 Etonian Messis 20 T15 Forlorn Hope 20 T22 058-g 19 T22 The MuckRakers 19 T22 a rum bunch 19 T22 Fritzl Palace 19 T22 Wadders' Winners 19 T22 Coalition of the (un)willing 19 T22 Followers of The Apocalypse 19 T22 Malcolm Tucker's Conscience 19 T30 Fansard 18 T30 What's left? 18 T30 Hocwatch 18 T30 everyone start wearing purple 18 T34 40-20 17 T34 Salmond en Croute 17 T34 The Right Hons 17 T34 Democratic doppelgangers 17 T34 Sevenofnine 17 T34 Oliver's Army 17 Position Team Name Current Points T34 KC's 17 T34 My redemption lies in your demise 17 T34 Lock the Doors! 17 T34 Antoine Donnelly Fan Club 17 T34 J.S. Gummer's Jolly Good Gunners 17 T34 Condolezza Spice 17 T34 Down and almost out 17 T34 get used to cliff 17 T48 Murphy's Law 16 T48 Calm Down Dear! 16 T48 The Real Gaal-aticos 16 T48 KFC (Keen For Conference): Politickin' good 16 T48 What do I Know? 16 T48 Team Squib 16 T48 Mencap Parliamentary Team 16 T48 Coalition United 16 T48 A nonet of ninnies 16 T48 Hail to the Chiefs 16 T48 Lady Thatcher's Legacy? 16 T48 The Social Democats -

Political Islam: a 40 Year Retrospective

religions Article Political Islam: A 40 Year Retrospective Nader Hashemi Josef Korbel School of International Studies, University of Denver, Denver, CO 80208, USA; [email protected] Abstract: The year 2020 roughly corresponds with the 40th anniversary of the rise of political Islam on the world stage. This topic has generated controversy about its impact on Muslims societies and international affairs more broadly, including how governments should respond to this socio- political phenomenon. This article has modest aims. It seeks to reflect on the broad theme of political Islam four decades after it first captured global headlines by critically examining two separate but interrelated controversies. The first theme is political Islam’s acquisition of state power. Specifically, how have the various experiments of Islamism in power effected the popularity, prestige, and future trajectory of political Islam? Secondly, the theme of political Islam and violence is examined. In this section, I interrogate the claim that mainstream political Islam acts as a “gateway drug” to radical extremism in the form of Al Qaeda or ISIS. This thesis gained popularity in recent years, yet its validity is open to question and should be subjected to further scrutiny and analysis. I examine these questions in this article. Citation: Hashemi, Nader. 2021. Political Islam: A 40 Year Keywords: political Islam; Islamism; Islamic fundamentalism; Middle East; Islamic world; Retrospective. Religions 12: 130. Muslim Brotherhood https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12020130 Academic Editor: Jocelyne Cesari Received: 26 January 2021 1. Introduction Accepted: 9 February 2021 Published: 19 February 2021 The year 2020 roughly coincides with the 40th anniversary of the rise of political Islam.1 While this trend in Muslim politics has deeper historical and intellectual roots, it Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral was approximately four decades ago that this subject emerged from seeming obscurity to with regard to jurisdictional claims in capture global attention.