Oxford Lecture 1 - Final Master

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EE British Academy Film Awards Sunday 12 February 2017 Previous Nominations and Wins in EE British Academy Film Awards Only

EE British Academy Film Awards Sunday 12 February 2017 Previous Nominations and Wins in EE British Academy Film Awards only. Includes this year’s nominations. Wins in bold. Years refer to year of presentation. Leading Actor Casey Affleck 1 nomination 2017: Leading Actor (Manchester by the Sea) Andrew Garfield 2 nominations 2017: Leading Actor (Hacksaw Ridge) 2011: Supporting Actor (The Social Network) Also Rising Star nomination in 2011, one nomination (1 win) at Television Awards in 2008 Ryan Gosling 1 nomination 2017: Leading Actor (La La Land) Jake Gyllenhaall 3 nominations/1 win 2017: Leading Actor (Nocturnal Animals) 2015: Leading Actor (Nightcrawler) 2006: Supporting Actor (Brokeback Mountain) Viggo Mortensen 2 nominations 2017: Leading Actor (Captain Fantastic) 2008: Leading Actor (Eastern Promises) Leading Actress Amy Adams 6 nominations 2017: Leading Actress (Arrival) 2015: Leading Actress (Big Eyes) 2014: Leading Actress (American Hustle) 2013: Supporting Actress (The Master) 2011: Supporting Actress (The Fighter) 2009: Supporting Actress (Doubt) Emily Blunt 2 nominations 2017: Leading Actress (Girl on the Train) 2007: Supporting Actress (The Devil Wears Prada) Also Rising Star nomination in 2007 and BAFTA Los Angeles Britannia Honouree in 2009 Natalie Portman 3 nominations/1 win 2017: Leading Actress (Jackie) 2011: Leading Actress (Black Swan) 2005: Supporting Actress (Closer) Meryl Streep 15 nominations / 2 wins 2017: Leading Actress (Florence Foster Jenkins) 2012: Leading Actress (The Iron Lady) 2010: Leading Actress (Julie -

GET BETTER FASTER: the Ultimate Guide to the Practice of Retrospectives

GET BETTER FASTER: The Ultimate Guide to the Practice of Retrospectives www.openviewlabs.com INTRODUCTION n 1945, the managers of a tiny car manufacturer in Japan took I It can cause the leadership team to be trapped inside a “feel-good stock of their situation and discovered that the giant firms of the bubble” where bad news is avoided or glossed over and tough U.S. auto industry were eight times more productive than their issues are not directly tackled. This can lead to an evaporating firm. They realized that they would never catch up unless they runway; what was assumed to be a lengthy expansion period can improved their productivity ten-fold. rapidly contract as unexpected problems cause the venture to run out of cash and time. Impossible as this goal seemed, the managers set out on a path of continuous improvement that 60 years later had transformed When done right, the retrospective review can be a powerful their tiny company into the largest automaker in the world and antidote to counteract these tendencies. driven the giants of Detroit to the very brink of bankruptcy. In that firm—Toyota—the commitment to continuous improve- This short handbook breaks down the key components of the ment is still a religion: over a million suggestions for improvement retrospective review. Inside you will learn why it is important, are received from their employees and dealt with each year. find details on how to go about it, and discover the pitfalls and difficulties that lie in the way of conducting retrospectives The key practice in the religion of continuous improvement is successfully. -

Sight & Sound Films of 2007

Sight & Sound Films of 2007 Each year we ask a selection of our contributors - reviewers and critics from around the world - for their five films of the year. It's a very loosely policed subjective selection, based on films the writer has seen and enjoyed that year, and we don't deny them the choice of films that haven't yet reached the UK. And we don't give them much time to ponder, either - just about a week. So below you'll find the familiar and the obscure, the new and the old. From this we put together the top ten you see here. What distinguishes this particular list is that it's been drawn up from one of the best years for all-round quality I can remember. 2007 has seen some extraordinary films. So all of the films in the ten are must-sees and so are many more. Enjoy. - Nick James, Editor. 1 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days (Cristian Mungiu) 2 Inland Empire (David Lynch) 3 Zodiac (David Fincher) = 4 I’m Not There (Todd Haynes) The Lives of Others (Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck) 6 Silent Light (Carlos Reygadas) = 7 The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford (Andrew Dominik) Syndromes and a Century (Apichatpong Weerasethakul) No Country for Old Men (Ethan and Joel Coen) Eastern Promises (David Cronenberg) 1 Table of Contents – alphabetical by critic Gilbert Adair (Critic and author, UK)............................................................................................4 Kaleem Aftab (Critic, The Independent, UK)...............................................................................4 Geoff Andrew (Critic -

Raquel Cassidy

www.hamiltonhodell.co.uk Raquel Cassidy Talent Representation Telephone Christopher Farrar +44 (0) 20 7636 1221 [email protected] Address Hamilton Hodell, 20 Golden Square London, W1F 9JL, United Kingdom Television Title Role Director Production Company THE GOOD KARMA HOSPITAL Frankie Phil John/Nimmer Rashed Tiger Aspect/ITV STRANGERS Rachel Paul Andrew Williams Two Brothers Pictures/ITV W1A Tamsin Gould John Morton BBC SILENT WITNESS Dr Eva Vazquez Dudi Appleton BBC THE HELLENES Bouboulina Van Ling Phaedra Films THE WORST WITCH 1-4 Hecate Hardbroom Various CBBC DOWNTON ABBEY Series 4, 5 & 6 Winner of the Outstanding Performance by an Ensemble in a Drama Series Award, Screen Actors Guild (SAG) Awards, 2016 Baxter Various Carnival/ITV Winner of the Outstanding Performance by an Ensemble in a Drama Series Award, Screen Actors Guild (SAG) Awards, 2015 HALF TIME (Pilot) Lucy Nick Walker Top Dog Productions MID MORNING MATTERS WITH ALAN PARTRIDGE Series 2 Hayley Rob Gibbons/Neil Gibbons Baby Cow/Fosters UNCLE Series 2 & 3 Teresa Oliver Refson Baby Cow/BBC VERA Series 5 Gloria Edwards Will Sinclair ITV JONATHAN CREEK Sharon David Renwick BBC LAW AND ORDER: UK Series 7 Lydia Smythson Joss Agnew Kudos/ITV LE GRAND Pauline Langlois Charlotte Sieling Atlantique Productions HEADING OUT Sabine Natalie Bailey BBC2 A TOUCH OF CLOTH Clare Hawkchurch Jim O'Hanlan Zeppotron Ltd MIDSOMER MURDERS Series 15: THE DARK RIDER Diana DeQuetteville Alex Pillai Bentley Productions HUSTLE Series 8 Dana Deville Roger Goldby Kudos DCI BANKS Dr. Waring Bill Anderson Left Bank Pictures teamWorx Television & Film THE OTHER CHILD D.I. -

Code Switching in Eastern Promises Film

Jurnal Ilmu Budaya Vol. 2, No. 3, Juni 2018 e-ISSN 2549-7715 Hal: 301-311 CODE SWITCHING IN EASTERN PROMISES FILM Rino Tri Wahyudi, M. Bahri Arifin, Ririn Setyowati English Department, Faculty of Cultural Sciences Mulawarman University Pos-el: [email protected] ABSTRACT Code switching is one of interesting topics to be discussed nowadays as it is often encountered by anyone and anywhere in the present time. Code switching appears in many literary works, and one of them is in Eastern Promises film. Eastern Promises film contains code switching of three different languages including English, Russian, and Turkish, and there is also evidence that code switching phenomenon exists in crime film. In criminal situation, the language user performs code switching for particular purposes. This research focused on analyzing the types of code switching and the social factors triggering the characters in performing code switching through descriptive qualitative research. The result of this research showed that there were eighty-one types of code switching found by the researcher in Eastern Promises film. The researcher found three types of code switching performed by ten characters, those types are inter-sentential code switching, tag switching, and intra-sentential code switching. In addition, the researcher also found four social factors in every code switching practices, those social factors are participant, setting, topic, and function. The social factors triggering the ten characters in performing code switching in their utterances show that language variety of the ten characters is a result of relationship between language and social factors that occurs in society. Keywords: code switching, Eastern Promises film ABSTRAK Alih kode adalah salah satu topik yang menarik untuk dibahas dewasa ini sebagaimana alih kode sering ditemui oleh siapapun dan dimanapun di masa sekarang. -

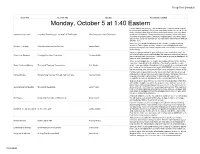

Download Deep Dive Schedule

Deep Dive Schedule Track Title Session Title Speaker Session Description Monday, October 5 at 1:40 Eastern "As the Father has sent me, I am sending you." How can you get out of the box of your building? Go to your community and meet a need. Create family fun days. Host special events and attract those in your city. Have Community Outreach Creatively Reaching Out: Go And Tell The People Miss PattyCake (Jean Thomason) a concert/movie/picnic. Reach into homes via media. Partner with other churches for greater impact. Become a brighter light in your area. Make and execute a plan for outreach so you can share God's big love with big and little lives. Have you ever wondered what goes into effective, creative teaching sessions? Take a journey inside Justyn's successful playbook as he Creative Teaching A Creative Process You Can Use Justyn Smith shares how anyone can create a system and environment of creativity in their ministry. Have you always wanted to give writing your own curriculum a try? Are you tired of using up your entire budget on expensive curriculum that you Curriculum Blueprint Creating Your Own Curriculum Corinne Noble have to heavily edit every week? Find out how to go from a blank page of paper to a full curriculum series. There is nothing quite like seeing the joy in a preschooler's face as they experience something for the first time. The joy of seeing them learn Early Childhood Ministry The Joy Of Teaching Preschoolers B.A. Snider about Jesus and laying a foundation for their growth in a relationship with the Creator of the universe is, in a word, AWESOME! Join me for some tips on teaching your young ones in this crazy, yet joyous, season of life. -

Ebook Download Ashes to Ashes Ebook Free Download

ASHES TO ASHES PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Tami Hoag | 593 pages | 01 Aug 2000 | Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group Inc | 9780553579604 | English | New York, United States Ashes to Ashes PDF Book Greil Marcus. Save Word. This site uses cookies and other tracking technologies to assist with navigation and your ability to provide feedback, analyse your use of our products and services, assist with our promotional and marketing efforts, and provide content from third parties. Ashes to ashes , funk to funky. See how we rate. Hunt's grass 'Rock Salmon' Doyle is murdered after divulging an upcoming heist, which Alex Steve Silberman and David Shenk. Share reduce something to ashes Post the Definition of reduce something to ashes to Facebook Share the Definition of reduce something to ashes on Twitter. User Reviews. The exploits of Gene Hunt continue in the hit drama series. Gene distrusts two former colleagues claiming to have travelled from Manchester on the hunt for an aged stand-up comedian who has allegedly stolen cash from the Police Widows' Fund. I hope that we find out a lot more about this compelling character in the future. Muse, Odalisque, Handmaiden. While the hard science of memorial diamonds is fascinating—a billion years in a matter of weeks! Creators: Matthew Graham , Ashley Pharoah. Queen: The Complete Works. When a violent burglary occurs at Alex's in-laws' house, she encounters their year-old son Peter - the future father of Molly. Learn More about reduce something to ashes Share reduce something to ashes Post the Definition of reduce something to ashes to Facebook Share the Definition of reduce something to ashes on Twitter Dictionary Entries near reduce something to ashes reducer sleeve reduce someone to silence reduce someone to tears reduce something to ashes reducible polynomial reducing agent reducing coupling. -

BBC 4 Listings for 5 – 11 April 2008 Page 1 of 3

BBC 4 Listings for 5 – 11 April 2008 Page 1 of 3 SATURDAY 05 APRIL 2008 Phill Jupitus narrates a series exploring 50 years of British TV SUN 01:05 Mozart: Sacred Music (b0074sfn) advertising, with this edition examining our love affair with [Repeat of broadcast at 20:00 today] SAT 19:00 Sounds of the Sixties (b009x6kv) technology. Adland has always made sure that people desire the Reversions latest model, from power tools and motor cars to stereo systems, flat-screen TVs and mobile phones. Contributors include Tim SUN 02:05 Sacred Music (b009phyw) The Folk Revival Bell, Sam Delaney, Alan Parker, Suzi Perry and India Knight. [Repeat of broadcast at 19:00 today] Bob Dylan and Leonard Cohen feature in this folk tinged episode of 60s archive. SUN 03:05 Legends (b009pgsc) SUNDAY 06 APRIL 2008 [Repeat of broadcast at 00:05 today] SAT 19:10 The Naked Civil Servant (b007yxxf) SUN 19:00 Sacred Music (b009phyw) Emmy award-winning film biography of Quentin Crisp, an Series 1 honest account of coming out in an era when the closet doors MONDAY 07 APRIL 2008 were closed. Tallis, Byrd and the Tudors MON 19:00 World News Today (b009s76b) Four-part documentary series in which Simon Russell Beale The latest news from around the world. SAT 20:30 Doctor Who (b009w0ll) explores the flowering of Western sacred music. Beale takes us The Daleks back to Tudor England, a country in turmoil as monarchs change the national religion and Roman Catholicism is driven MON 19:30 Pop Go the Sixties (b008d06d) The Dead Planet underground. -

Shameless Television: Gendering Transnational Narratives

This is a repository copy of Shameless television: gendering transnational narratives. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/129509/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Johnson, B orcid.org/0000-0001-7808-568X and Minor, L (2019) Shameless television: gendering transnational narratives. Feminist Media Studies, 19 (3). pp. 364-379. ISSN 1468-0777 https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2018.1468795 Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Shameless Television: Gendering Transnational Narratives Beth Johnson ([email protected]) and Laura Minor ([email protected]) School of Media and Communication, University of Leeds, Leeds, UK Abstract The UK television drama Shameless (Channel 4, 2004-2011) ran for eleven series, ending with its 138th episode in 2011. The closing episode did not only mark an end, however, but also a beginning - of a US remake on Showtime (2011-). Eight series down the line and carrying the weight of critical acclaim, this article works to consider the textual representations and formal constructions of gender through the process of adaptation. -

Mothers on Mothers: Maternal Readings of Popular Television

From Supernanny to Gilmore Girls, from Katie Price to Holly Willoughby, a MOTHERS ON wide range of examples of mothers and motherhood appear on television today. Drawing on questionnaires completed by mothers across the UK, this MOTHERS ON MOTHERS book sheds new light on the varied and diverse ways in which expectant, new MATERNAL READINGS OF POPULAR TELEVISION and existing mothers make sense of popular representations of motherhood on television. The volume examines the ways in which these women find pleasure, empowerment, escapist fantasy, displeasure and frustration in popular depictions of motherhood. The research seeks to present the MATERNAL READINGS OF POPULAR TELEVISION voice of the maternal audience and, as such, it takes as its starting REBECCA FEASEY point those maternal depictions and motherwork representations that are highlighted by this demographic, including figures such as Tess Daly and Katie Hopkins and programmes like TeenMom and Kirstie Allsopp’s oeuvre. Rebecca Feasey is Senior Lecturer in Film and Media Communications at Bath Spa University. She has published a range of work on the representation of gender in popular media culture, including book-length studies on masculinity and popular television and motherhood on the small screen. REBECCA FEASEY ISBN 978-0343-1826-6 www.peterlang.com PETER LANG From Supernanny to Gilmore Girls, from Katie Price to Holly Willoughby, a MOTHERS ON wide range of examples of mothers and motherhood appear on television today. Drawing on questionnaires completed by mothers across the UK, this MOTHERS ON MOTHERS book sheds new light on the varied and diverse ways in which expectant, new MATERNAL READINGS OF POPULAR TELEVISION and existing mothers make sense of popular representations of motherhood on television. -

Scott & Bailey 2 Wylie Interviews

Written by Sally Wainwright 2 PRODUCTION NOTES Introduction .........................................................................................Page 3 Regular characters .............................................................................Page 4 Interview with writer and co-creator Sally Wainwright ...................Page 5 Interview with co-creator Diane Taylor .............................................Page 8 Suranne Jones is D.C. Rachel Bailey ................................................Page 11 Lesley Sharp is D.C. Janet Scott .......................................................Page 14 Amelia Bullmore is D.C.I. Gill Murray ................................................Page 17 Nicholas Gleaves is D.S. Andy Roper ...............................................Page 20 Sean Maguire is P.C. Sean McCartney ..............................................Page 23 Lisa Riley is Nadia Hicks ....................................................................Page 26 Kevin Doyle is Geoff Hastings ...........................................................Page 28 3 INTRODUCTION Suranne Jones and Lesley Sharp resume their partnership in eight new compelling episodes of the northern-based crime drama Scott & Bailey. Acclaimed writer and co-creator Sally Wainwright has written the second series after once again joining forces with Consultancy Producer Diane Taylor, a retired Detective from Greater Manchester Police. Their unique partnership allows viewers and authentic look at the realities and responsibilities of working within -

Fantastika Journal

FANTASTIKAJOURNAL After Bowie: Apocalypse, Television and Worlds to Come Andrew Tate Volume 4 Issue 1 - After Fantastika Stable URL: https:/ /fantastikajournal.com/volume-4-issue-1 ISSN: 2514-8915 This issue is published by Fantastika Journal. Website registered in Edmonton, AB, Canada. All our articles are Open Access and free to access immediately from the date of publication. We do not charge our authors any fees for publication or processing, nor do we charge readers to download articles. Fantastika Journal operates under the Creative Commons Licence CC-BY-NC. This allows for the reproduction of articles for non-commercial uses, free of charge, only with the appropriate citation information. All rights belong to the author. Please direct any publication queries to [email protected] www.fantastikajournal.com Fantastika Journal • Volume 4 • Issue 1 • July 2020 AFTER BOWIE: APOCALYPSE, TELEVISION AND WORLDS TO COME Andrew Tate Let’s start with an image or, more accurately, an image of images from a 1976 film. A character called Thomas Jerome Newton is surrounded by the dazzle and blaze of a bank of television screens. He looks vulnerable, overwhelmed and enigmatic. The moment is an oddly perfect metonym of its age, one that speaks uncannily of commercial confusion, artistic innovation and political inertia. The film is Nic Roeg’s The Man Who Fell to Earth – an adaptation of Walter Tevis’ 1963 novel – and the actor on screen is David Bowie, already celebrated for his multiple, mutable pop star identities in his first leading role in a motion picture. In an echo of what Nicholas Pegg has called “the ongoing sci-fi shtick that infuses his most celebrated characters” – including by this time, for example, Major Tom of “Space Oddity” (1969), rock star messiah Ziggy Stardust and the post-apocalyptic protagonists of “Drive-In Saturday” (1972) – he performs the role of an alien (Kindle edition, location 155).