Reconstruction of the Largest Pedigree Network for Pear Cultivars and Evaluation of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Choosing the Right Tree to Plant

Prunus / Cherry flower Choosing the right tree to plant Choosing what tree to plant can be difficult with the buildings, shading, overhanging roads and footpaths number of different species, cultivars and varieties that etc.? It may not be sensible to replace a large forest are currently available. There are a number of useful type tree in a small domestic garden with another one books and websites, but if you are still unsure it may be unless you are prepared to remove it before it outgrows useful to visit a garden or arboretum. There are some its situation. basic points that should be considered as follows. Benefits - as well as having obvious ornamental Soil - will the tree grow well in the soil in which is to be attributes, trees provide shelter, reduce temperature planted? Acidity, drainage and the type of soil will all extremes and produce oxygen. have a bearing. Some tree species are more specific than others as to their requirements. Once you have decided on your tree, the next step is to purchase it. Please bear in mind that if you have Local distinctiveness - what species grow naturally in removed a protected tree (that is one growing in a the area already? Native species are usually best for conservation area or subject to a tree preservation wildlife and ‘fit in’ with the landscape character and are order) there may either be a duty (as in the case of normally preferable to ornamental species. dead or dangerous trees) or a condition (in the case of a tree preservation order application) requiring the Available space - is the tree able to reach its full planting of a replacement tree. -

Proceedings of Workshop on Gene Conservation of Tree Species–Banking on the Future May 16–19, 2016, Holiday Inn Mart Plaza, Chicago, Illinois, USA

United States Department of Agriculture Proceedings of Workshop on Gene Conservation of Tree Species–Banking on the Future May 16–19, 2016, Holiday Inn Mart Plaza, Chicago, Illinois, USA Forest Pacific Northwest General Technical Report September Service Research Station PNW-GTR-963 2017 Pacific Northwest Research Station Web site http://www.fs.fed.us/pnw Telephone (503) 808-2592 Publication requests (503) 808-2138 FAX (503) 808-2130 E-mail [email protected] Mailing address Publications Distribution Pacific Northwest Research Station P.O. Box 3890 Portland, OR 97208-3890 Disclaimer Papers were provided by the authors in camera-ready form for printing. Authors are responsible for the content and accuracy. Opinions expressed may not necessarily reflect the position of the U.S. Department of Agriculture. The use of trade or firm names in this publication is for reader information and does not imply endorsement by the U.S.Department of Agriculture of any product or service. Technical Coordinators Richard A. Sniezko is center geneticist, U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service, Dorena Genetic Resource Center, 34963 Shoreview Road, Cottage Grove, OR 97424 (e-mail address: [email protected]) Gary Man is a Forest health special- ist, U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service, State and Private Forestry, Forest Health Protection, 201 14th St SW 3rd FL CE, Washington DC 20024 (e-mail address: [email protected]) Valerie Hipkins is lab director, U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service, National Forest Genetics Laboratory, 2480 Carson Road, Placerville, CA 95667 (e-mail address: [email protected]) Keith Woeste is research geneti- cist, U.S. -

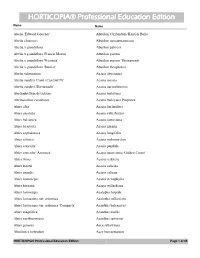

Education Edition List For

HORTICOPIA® Professional Education Edition Name Name Abelia 'Edward Goucher' Abutilon x hybridum 'Kentish Belle' Abelia chinensis Abutilon megapotamicum Abelia x grandiflora Abutilon palmeri Abelia x grandiflora 'Francis Mason' Abutilon pictum Abelia x grandiflora 'Prostrata' Abutilon pictum 'Thompsonii' Abelia x grandiflora 'Sunrise' Abutilon theophrasti Abelia schumannii Acacia abyssinica Abelia zanderi 'Conti (Confetti™)' Acacia aneura Abelia zanderi 'Sherwoodii' Acacia auriculiformis Abeliophyllum distichum Acacia baileyana Abelmoschus esculentus Acacia baileyana 'Purpurea' Abies alba Acacia berlandieri Abies amabilis Acacia cultriformis Abies balsamea Acacia farnesiana Abies bracteata Acacia greggii Abies cephalonica Acacia longifolia Abies cilicica Acacia melanoxylon Abies concolor Acacia pendula Abies concolor 'Argentea' Acacia pravissima 'Golden Carpet' Abies firma Acacia redolens Abies fraseri Acacia salicina Abies grandis Acacia saligna Abies homolepis Acacia stenophylla Abies koreana Acacia willardiana Abies lasiocarpa Acalypha hispida Abies lasiocarpa ssp. arizonica Acalypha wilkesiana Abies lasiocarpa ssp. arizonica 'Compacta' Acanthus balcanicus Abies magnifica Acanthus mollis Abies nordmanniana Acanthus spinosus Abies procera Acca sellowiana Abutilon x hybridum Acer buergerianum HORTICOPIA® Professional Education Edition Page 1 of 65 Name Name Acer campestre Acer palmatum (Dissectum Group) 'Crimson Queen' Acer capillipes Acer palmatum (Dissectum Group) 'Inaba shidare' Acer cappadocicum Acer palmatum (Dissectum Group) 'Red -

Rosaceae): a New Record and a New Synonym, with Data on Seed Morphology

Plant & Fungal Research (2019) 2(1): 2-8 © The Institute of Botany, ANAS, Baku, AZ1004, Azerbaijan http://dx.doi.org/10.29228/plantfungalres.11 June 2019 Taxonomic and biogeographic notes on the genus Pyrus L. (Rosaceae): a new record and a new synonym, with data on seed morphology Zübeyde Uğurlu Aydın¹ Iran, Central Asia and Afghanistan, while oriental pears Ali A. Dönmez are widespread in East Asia. Pyrus pashia is accepted Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Hacettepe University, as a link between Occidental and Oriental pear species Beytepe, Ankara, Turkey. [Rubtsov, 1944; Zheng et al., 2014] because it is native to China, Bhutan, India, Kashmir, Laos, Myanmar, Ne- Abstract: Species of the genus Pyrus distributed in Eu- pal, the western part of Pakistan, Thailand, Vietnam, Af- rope include P. communis L., P. pyraster, P. nivalis Jacq., ghanistan [Gu & Spongberg, 2003], and have been also and P. cordata Desv. subsp. cordata. Pyrus pyraster is recently recorded from northeastern Iran [Zamani et al., occasionally regarded as a variety or subspecies of P. 2009]. It is placed in Pyrus sect. Pashia, with morpho- communis. However, a molecular study has recently logically similar P. cordata Desv. subsp. boissieriana demonstrated that P. communis is more closely related (Buhse) Uğurlu & Dönmez. These taxa also share simi- to P. caucasica and P. nivalis, rather than to P. pyraster. lar distribution patterns, and their taxonomic delimita- In this study, Pyrus pyraster is reported from Turkey for tions remain unclear [Zamani et al., 2009]. In order to the first time. Pyrus vallis-demonis, a species recently close this gap, a detailed description of P. -

Pyrus Cordata Desv

Pyrus cordata Desv. Identifiants : 26470/pyrcor Association du Potager de mes/nos Rêves (https://lepotager-demesreves.fr) Fiche réalisée par Patrick Le Ménahèze Dernière modification le 25/09/2021 Classification phylogénétique : Clade : Angiospermes ; Clade : Dicotylédones vraies ; Clade : Rosidées ; Clade : Fabidées ; Ordre : Rosales ; Famille : Rosaceae ; Classification/taxinomie traditionnelle : Règne : Plantae ; Sous-règne : Tracheobionta ; Division : Magnoliophyta ; Classe : Magnoliopsida ; Ordre : Rosales ; Famille : Rosaceae ; Genre : Pyrus ; Nom(s) anglais, local(aux) et/ou international(aux) : Plymouth Pear, Pear , Basomakatza, Perojo, Peruyes ; Note comestibilité : ** Rapport de consommation et comestibilité/consommabilité inférée (partie(s) utilisable(s) et usage(s) alimentaire(s) correspondant(s)) : Parties comestibles : fruit{{{0(+x) (traduction automatique) | Original : Fruit{{{0(+x) Les fruits sont consommés très mûrs et de préférence après stockage. Ils sont également utilisés pour faire une boisson néant, inconnus ou indéterminés. Illustration(s) (photographie(s) et/ou dessin(s)): Autres infos : dont infos de "FOOD PLANTS INTERNATIONAL" : Distribution : C'est une plante tempérée ou méditerranéenne. Arboretum Tasmania{{{0(+x) (traduction automatique). Original : It is a temperate or Mediterranean plant. Arboretum Tasmania{{{0(+x). Page 1/2 Localisation : Australie, Grande-Bretagne, Europe, Méditerranée, Espagne, Tasmanie{{{0(+x) (traduction automatique). Original : Australia, Britain, Europe, Mediterranean, Spain, Tasmania{{{0(+x). Liens, sources et/ou références : 5"Plants For a Future" (en anglais) : https://pfaf.org/user/Plant.aspx?LatinName=Pyrus_cordata ; dont classification : dont livres et bases de données : 0"Food Plants International" (en anglais) ; dont biographie/références de 0"FOOD PLANTS INTERNATIONAL" : Menendez-Baceta, G., et al, 2012, Wild edible plants traditionally gathered in Gorbeialdea (Biscay, Basque Country) Genetic Reources and Crop Evolution 59:1329-1347 ; Observ. -

Isolation and Characterization of Putative Functional Long Terminal

Jiang et al. Mobile DNA (2016) 7:1 DOI 10.1186/s13100-016-0058-8 RESEARCH Open Access Isolation and characterization of putative functional long terminal repeat retrotransposons in the Pyrus genome Shuang Jiang1,2, Danying Cai3, Yongwang Sun1,4,5 and Yuanwen Teng1,4,5* Abstract Background: Long terminal repeat (LTR)-retrotransposons constitute 42.4 % of the genome of the ‘Suli’ pear (Pyrus pyrifolia white pear group), implying that retrotransposons have played important roles in Pyrus evolution. Therefore, further analysis of retrotransposons will enhance our understanding of the evolutionary history of Pyrus. Results: We identified 1836 LTR-retrotransposons in the ‘Suli’ pear genome, of which 440 LTR-retrotransposons were predicted to contain at least two of three gene models (gag, integrase and reverse transcriptase). Because these were most likely to be functional transposons, we focused our analyses on this set of 440. Most of the LTR-retrotransposons were estimated to have inserted into the genome less than 2.5 million years ago. Sequence analysis showed that the reverse transcriptase component of the identified LTR-retrotransposons was highly heterogeneous. Analyses of transcripts assembled from RNA-Seq databases of two cultivars of Pyrus species showed that LTR-retrotransposons were expressed in the buds and fruit of Pyrus. A total of 734 coding sequences in the ‘Suli’ genome were disrupted by the identified LTR-retrotransposons. Five high-copy-number LTR-retrotransposon families were identified in Pyrus. These families were rarely found in the genomes of Malus and Prunus, but were distributed extensively in Pyrus and abundance varied between species. Conclusions: We identified potentially functional, full-length LTR-retrotransposons with three gene models in the ‘Suli’ genome. -

Progress in Pear Improvement

PROGRESS IN PEAR IMPROVEMENT J. R. MAGNESS, Principal Pomologist, Division of Fruit and Vegetable Crops and Diseases, Bureau of Plant Industry X HE pear, like the apple, first came to us from western Asia by way of European countries. Its history in Europe closely parallels that of the apple. Apparently indigenous in the region from the Caspian Sea westward into Europe, whence so many of our fruits came, the pear was doubtless used as food long before agriculture was developed as an industry. ^ Hedrick, in the Pears of New York, gives an excellent summary of its history and development during the last 3,000 years. Nearly 1,000 years before the Christian Era, Homer listed pears as one of the fruits in the garden of Alcinous, thus indicating that they were known to the Greeks of his day. Prior to the Christian Era at least a few varieties were known. Theophrastus (370-286 B. C.) mentioned both wild pears and cultivated named varieties and de- scribed grafting. Pliny, of ancient Rome, named more than 40 varieties. With the migrations of the Romans the pear was distrib- uted throughout temperate Europe. At the time of the discovery of North America, a number of varieties were known in Italy, France, Germany, and England, but there was little progress in the culture of the pear, at least as far as is known, from the early Christian Era until about the beginning of the sixteenth century. During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, there was a tre- mendous interest in pear breeding and improvement, particularly in Belgium and France. -

Growing Cider Apples

MAY 2008 PRIMEFACT 796 (REPLACES AGFACT H4.1.11) Growing cider apples David Pickering damage to cider fruit does not present anywhere Technical Officer, Science and Research, Orange near as much of a problem as it does in dessert fruit. Harvesting. The crop can be mechanically harvested (see warning notes under ‘Rootstocks’) Introduction since the apple-crushing procedure is usually Growing cider apples is very similar to growing carried out shortly after harvesting. The pulping and dessert apple varieties. They have similar cultural pressing processes quickly nullify any bruising of requirements of climate, soils, site selection, the fruit caused during the harvest. However, if the nutrition, irrigation and pest and disease control. fruit is to be stored for a period before it is processed, then the overall quality of the finished juice product will be reduced if there are significant Making cider quantities of bruised and damaged fruit. Cider is made by pressing apples to produce juice, The equipment used in a mechanical harvesting then fermenting that juice to make cider. Most operation can include tree shakers, blowers, commercial ciders available in Australia are a blend sweepers and washers. of dessert and cider apple varieties, although cider can be made exclusively from cider apple juice. Biennial bearing The term ‘cider’ is used in Britain and Europe in much the same way as it is used in Australia, i.e. to Biennial bearing, where heavy yields one year are refer to the fermented and therefore alcoholic followed by light or non-existent yields the next, product. Cider is also a popular drink in France can be a major problem with some cider varieties. -

Dwarfing-Canopy and Rootstock Cultivars for Fruit Trees

ISSN 0100-2945 DOI: http://dx.doi.org /10.1590/0100-29452019997 Propagation Dwarfing-canopy and rootstock cultivars for fruit trees 1 2 3 4 Luiz Carlos Donadio , Ildo Eliezer Lederman , Sergio Ruffo Roberto , Eduardo Sanches Stucchi Abstract - As fruit trees generally have a large size, the production of small or even dwarf trees is of great interest for most of fruit crops. In this review, some of the main tropical, subtropical and temperate fruit trees that have small or even dwarfing cultivars are approached. The causes of dwarfism, although the use of dwarfing rootstocks, is the main theme of this review. The factors that affect the size of the fruit trees are also approached, as well the dwarf cultivars of banana, papaya and cashew, and the dwarf rootstocks for guava, mango, anonaceae, loquat, citrus, apple and peach trees. Index terms: high-density plantings; spacings; dwarf fruit trees. Cultivares-copa e porta-enxertos ananicantes para plantas frutíferas Resumo - Como as plantas frutíferas apresentam em geral porte elevado, a obtenção de plantas de porte reduzido, ou até anãs, é de grande interesse na fruticultura. Nesta revisão são comentadas algumas das principais plantas frutíferas de clima tropical, subtropical ou temperado que têm variedades de porte reduzido, ou mesmo anãs. As causas do nanismo e o uso de porta-enxertos ananicantes são os principais temas desta revisão. São abordados também os fatores que afetam o porte das plantas frutíferas, as variedades-copa anãs em bananeira, mamoeiro e cajueiro, bem como os porta-enxertos ananicantes para goiabeira, mangueira, anonáceas, nespereira, citros, macieira e pessegueiro. -

Pyrus Cordata Desv. Plymouth Pear

Pyrus cordata Desv. Plymouth Pear Starting references Family Rosaceae IUCN category (2001) Vulnerable Habit Small hedgerow tree up to 10 m high. Habitat type It is impossible to determine its favoured habitat as the plants occur in only two locations that are intensively managed. Reasons for decline Rare populations and low seed-fertility. Distribution in wild Country Locality & Vice County Sites Population (10km2 (plants) occurences) England A light-industrial estate in Plymouth and near Truro 7 few Ex situ Collections Gardens close to the region of distribution of the species 1 St Michael’s Mount (NT) 2 Duchy College 3 Trebah Garden Trust 4 Glendurgan Gardens 5 Trellisick (NT) 6 Tregothnan Botanic Garden 7 Eden Project 8 Lilac Cottage 9 Tregrehan Gardens of specialisation on genus Pyrus Brogdale Horticultural Trust York Museum Gardens Potential to grow the species in ex situ Collections From Plants For A Future • Propagation Propagation by seed - best sown in a cold frame as soon as it is ripe in the autumn, it will then usually germinate in mid to late winter. Stored seed requires 8 - 10 weeks cold stratification at 1°c and should be sown as early in the year as possible. Temperatures over 15 - 20°c induce a secondary dormancy in the seed. Prick out the seedlings into individual pots when they are large enough to handle and grow them on in light shade in a cold frame or greenhouse for their first year. Plant them out in late spring or early summer of the following year. • Cultivation Prefers a good well-drained loam in full sun. -

Report of a Working Group on Malus/Pyrus

Report of a Working Group on Malus/Pyrus Second Meeting 2–4 May 2002, Dresden-Pillnitz, Germany L. Maggioni, M. Fischer, M. Lateur, E.-J. Lamont and E. Lipman, compilers <www.futureharvest.org> IPGRI is a Future Harvest Centre supported by the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) Report of a Working ECP GR Group on Malus/Pyrus Second Meeting 2–4 May 2002, Dresden-Pillnitz, Germany L. Maggioni, M. Fischer, M. Lateur, E.-J. Lamont and E. Lipman, compilers ii REPORT OF A WORKING GROUP ON MALUS/PYRUS: SECOND MEETING The International Plant Genetic Resources Institute (IPGRI) is an independent international scientific organization that seeks to advance the conservation and use of plant genetic diversity for the well-being of present and future generations. It is one of 16 Future Harvest Centres supported by the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR), an association of public and private members who support efforts to mobilize cutting-edge science to reduce hunger and poverty, improve human nutrition and health, and protect the environment. IPGRI has its headquarters in Maccarese, near Rome, Italy, with offices in more than 20 other countries worldwide. The Institute operates through three programmes: (1) the Plant Genetic Resources Programme, (2) the CGIAR Genetic Resources Support Programme and (3) the International Network for the Improvement of Banana and Plantain (INIBAP). The international status of IPGRI is conferred under an Establishment Agreement which, by January 2003, had been signed by the Governments of Algeria, Australia, Belgium, Benin, Bolivia, Brazil, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Chile, China, Congo, Costa Rica, Côte d’Ivoire, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Ecuador, Egypt, Greece, Guinea, Hungary, India, Indonesia, Iran, Israel, Italy, Jordan, Kenya, Malaysia, Mauritania, Morocco, Norway, Pakistan, Panama, Peru, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russia, Senegal, Slovakia, Sudan, Switzerland, Syria, Tunisia, Turkey, Uganda and Ukraine. -

Printemps 2005

6099_Couverture 30/05/05 16:35 Page 1 6099_Couverture 30/05/05 16:35 Page 2 à suivre n° 9 - été 2005 Prochain dossier : les réseaux naturalistes de l'ONF parution : août 2005 Connaître les réseaux naturalistes et les travaux qu'ils mènent : tel est le cœur de ce prochain dossier très pratique qui présentera les réseaux naturalites, et illustrera à travers différents cas concrets les éléments qu'ils peuvent apporter au gestionnaire. Retrouvez RenDez-Vous techniques sur intraforêt Tous les textes de ce numéro sont accessibles au format PDF dans la rubrique qui lui est désormais consacrée dans le portail de la direction technique (Recherche et développement/Documentation technique). Accès direct à partir du sommaire. MailMail : [email protected]@onf.fr 6099_P_01_68 1/06/05 11:51 Page 1 n° 8 - printemps 2005 3 pratiques Pommiers et poiriers sauvages : comment les reconnaître ? par Thierry Lamant et Laurent Lévêque 7 pratiques Pommiers et poiriers sauvages en forêt par Thierry Lamant et Laurent Lévêque 15 méthodes Évaluer la potentialité forestière d'un site sans observer la flore par Christian Ripert et Michel Vennetier 23 dossier thématique Tassements du sol 52 pratiques Conséquences de la sécheresse et de la canicule 2003 par Frédéric Mortier, Jean-Claude Chopart et Thierry Sardin 57 pratiques Cartographie au GPS des routes forestières d'Alsace par Gérard Patzelt, Jean-Louis Besson, Laurent Gautier et Pierre Geldreich 64 pratiques Plantation en milieu acide hydromorphe par Anne Laybourne, Loïc Nicolas et Xavier Mandret RDV techniques n° 8 - printemps 2005 - ONF 6099_P_01_68 27/05/05 17:06 Page 2 éditorial ans ces nouveaux « Rendez-vous techniques », nous avons tenu à attirer votre attention sur unD compartiment essentiel de l'écosystème forestier : le sol.