Jorge Secada

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summer Camp Song Book

Summer Camp Song Book 05-209-03/2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Numbers 3 Short Neck Buzzards ..................................................................... 1 18 Wheels .............................................................................................. 2 A A Ram Sam Sam .................................................................................. 2 Ah Ta Ka Ta Nu Va .............................................................................. 3 Alive, Alert, Awake .............................................................................. 3 All You Et-A ........................................................................................... 3 Alligator is My Friend ......................................................................... 4 Aloutte ................................................................................................... 5 Aouettesky ........................................................................................... 5 Animal Fair ........................................................................................... 6 Annabelle ............................................................................................. 6 Ants Go Marching .............................................................................. 6 Around the World ............................................................................... 7 Auntie Monica ..................................................................................... 8 Austrian Went Yodeling ................................................................. -

FMC Flea and Farmers Market Study Appendix

French Market Flea & Farmers Market Study Appendix This appendix includes all of the documents produced during the engagement and study process for the French Market. Round 1 Engagement Summary Round 2 Engagement Summary ROUND 1 STAKEHOLDER ROUND 2 STAKEHOLDER ENGAGEMENT SUMMARY ENGAGEMENT SUMMARY Vendor Meeting Jan. 21, 8-10 AM Public Virtual Meeting Public Virtual Meeting February 25, 6-7 PM Jan. 21, 6-8 PM Public Survey Culture Bearer Meeting February 25 - March 12 Feb. 11, 12-1 PM Round 3 Engagement Summary Public Bathing Research Document Round 3 Stakeholder ADDENDUM: PUBLIC TOILETS AND SHOWERS Engagement Takeaways Bathrooms at the French Market Stakeholders offered the following feedback after reviewing preliminary recommendations for each category: Findings about plumbing, public toilets and showers Policy Research findings: • Provide increased support for janitorial staff and regular, deep cleaning of bathrooms and facilities • Estate clear policies and coordination needed for vendor loading and parking An initial search into public hygiene facilities has yielded various structures • Incentivize local artists to be vendors by offering rent subsidies for local artist and artisan vendors who hand-make their products. and operating models, all of which present opportunities for addressing • Designate a specific area for local handmade crafts in the market, that is separate from other products so the FMC’s desire to support its vendors, customers, and the surrounding community. customers know where to find them. • Vendor management software and apps work for younger vendors but older vendors should be able to Cities, towns, municipalities and non-profit organizations, alone and in partnership, have access the same information by calling or talking to FMC staff in person. -

The Rockefeller Institute Review 1963, Vol. 1, No. 3 the Rockefeller University

Rockefeller University Digital Commons @ RU The Rockefeller Institute Review The Rockefeller University Newsletters 6-1963 The Rockefeller Institute Review 1963, vol. 1, no. 3 The Rockefeller University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.rockefeller.edu/ rockefeller_institute_review Recommended Citation The Rockefeller University, "The Rockefeller Institute Review 1963, vol. 1, no. 3" (1963). The Rockefeller Institute Review. Book 3. http://digitalcommons.rockefeller.edu/rockefeller_institute_review/3 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the The Rockefeller University Newsletters at Digital Commons @ RU. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Rockefeller Institute Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ RU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ROCKEFELLERINSTITUTE REVIEW, June 1963. Issued in February, April, June, August, October, De- cember. This is volume 1 number 3. Published by The Rockefeller Institute, 66th Street and York Avenue, New York 21, New York. Application to mail at second-class postage rate is pending at New York, N. Y. Copyright O 1963 by The Rockefeller Institute Press. Printed in the United States of America. TWO VOICES: SCIENCE AND LITERATURE , BY MARJORIE HOPE NICOLSON ius," both titles well deserved. There were revolu- \\ tions in politics, in religion, in society, in economics. I HAVE TAKEN my title from the opening phrase of one But a century that has left a roster of such names as of Wordsworth's sonnets on liberty: those of Harvey, Kepler, Galileo, Boyle, Newton, as Two voices are there; one is of the sea, Bruno, Bacon, Hobbes, Spinoza, Leibniz, Locke, One of the mountains; each a mighty voice. -

Bellwether 1, Fall 1981

Bellwether Magazine Volume 1 Number 1 Fall 1981 Article 1 Fall 1981 Bellwether 1, Fall 1981 Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/bellwether Part of the Veterinary Medicine Commons Recommended Citation (1981) "Bellwether 1, Fall 1981," Bellwether Magazine: Vol. 1 : No. 1 , Article 1. Available at: https://repository.upenn.edu/bellwether/vol1/iss1/1 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/bellwether/vol1/iss1/1 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Newsletter of the School of Veterinary Medicine Amelia C. Van Buren Thomas Eakins Photograph, c. 1891 Philadelphia Museum of Art Given by Seymour Adelman Humans& Companion Animals A Relationship Explored Animals have always been a part of In an urban society, the need for School of Veterinary Medicine of the human experience, not just as a companionship is as great as ever University of Pennsylvania will host source of food, but also as a source and companion animals play an an international conference on the of companionship. Consider the important role in the lives of people. Human/ Companion Animal Bond multitude of breeds of dogs and cats The bond between people and October 5 through 7. According to and you'll realize that animal com· animals has long been acknowl· Dr. Alan M. Beck, director of the panions are important to people. edged, although it has not really center, this will be the first confer Many breeds were originally devel been studied scientifically until ence ever held in the United States oped to fulfill a function, such as recently. -

English Reading List

Suggested Readings for the Comprehensive Exam of the English Department of the University of the South Given the limited time we have with our majors, we must acknowledge that the readings they undertake in the English curriculum are only a stone’s skip across a wide and rich expanse of literary waters. The following list is likewise not a comprehensive list of literary touchstones, but it is intended as a guide as you follow your own intellectual interests and curiosities. We expect that in your courses you’ll read substantially but not exhaustively from the works listed here, and that you’ll also read a number of works that do not appear on the list. Let your preparation for the comprehensive exam be an occasion to revisit the novels, poems, and plays that you’ve read closely in your classes as well as an opportunity to extend your independent explorations of the literary canon. Your professors recommend this guide as a useful map for you in these explorations, both while you are in Sewanee and in the years to follow. Students are encouraged to purchase The Norton Anthology of English Literature (2 volumes) and The Norton Anthology of American Literature and to familiarize themselves with their contents. These anthologies include a generous sampling of the works mentioned below, and they contain introductions to different literary periods and movements can help you refine your sense of periods and connections. Recommended histories of English literature includes Albert C. Baugh’s A Literary History of England[1] A useful popular history is available in a Norton paperback edition: The Land and Literature of England, by Robert M. -

Traces of Trauma in Post-War Polish Photography

Exposing Wounds: Traces of Trauma in Post-War Polish Photography Sabina Gill A thesis submitted for the degree of PhD Department of Philosophy & Art History University of Essex May 2017 2 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My gratitude must firstly be extended to my supervisor Maggie Iversen, who I increasingly believe must have the patience of a saint. The support from Tate needs acknowledgement, firstly from my supervisor Simon Baker, but also Kasia Redzisz in the Curatorial department, and Nigel Llewellyn and Helen Griffiths in the Research Department, who greatly assisted me in organising a research seminar on Polish photography at Tate Modern in June 2013. My gratitude also extends to all those who participated in the seminar, especially to those who presented papers: Karolina Lewandowska, who co-organised the event, Sylwia Serafinowicz, Marika Kuźmicz, Sarah James, Krzysztof Pijarski, and Chantal Pontbriand. The encouragement and enthusiasm of fellow Collaborative Doctoral Award Students at Tate has also been stimulating. Thank you to Karolina Lewandowska and Rafał Lewandowski, both for the extraordinary access they offered to the archives of the Archaeology of Photography Foundation and Galeria Asymetria in Warsaw for the purposes of my research, but also for their hospitality in welcoming me into their home and sharing their extensive archive of photography magazines. I would like to thank the many Polish artists and curators who have taken the time to discuss the topic of Polish photography with me: Krzysztof Jurecki, Marika Kuzmicz, Adam Mazur, Cezary Piekary, Krzysztof Pijarski, Adam Sobota, Józef Robakowski, and Andrzej Różycki, all of whom have contributed to the content of this thesis. -

History, Rats, Fleas, and Opossums. II. the Decline and Resurgence of Flea-Borne Typhus in the United States, 1945–2019

Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease Review History, Rats, Fleas, and Opossums. II. The Decline and Resurgence of Flea-Borne Typhus in the United States, 1945–2019 Gregory M. Anstead Medical Service, South Texas Veterans Health Care System and Department of Medicine, University of Texas Health San Antonio, San Antonio, TX 78229, USA; [email protected] Abstract: Flea-borne typhus, due to Rickettsia typhi and R. felis, is an infection causing fever, headache, rash, and diverse organ manifestations that can result in critical illness or death. This is the second part of a two-part series describing the rise, decline, and resurgence of flea-borne typhus (FBT) in the United States over the last century. These studies illustrate the influence of historical events, social conditions, technology, and public health interventions on the prevalence of a vector-borne disease. Flea-borne typhus was an emerging disease, primarily in the Southern USA and California, from 1910 to 1945. The primary reservoirs in this period were the rats Rattus norvegicus and Ra. rattus and the main vector was the Oriental rat flea (Xenopsylla cheopis). The period 1930 to 1945 saw a dramatic rise in the number of reported cases. This was due to conditions favorable to the proliferation of rodents and their fleas during the Depression and World War II years, including: dilapidated, overcrowded housing; poor environmental sanitation; and the difficulty of importing insecticides and rodenticides during wartime. About 42,000 cases were reported between 1931–1946, and the actual number of cases may have been three-fold higher. The number of annual cases of FBT peaked in 1944 at 5401 cases. -

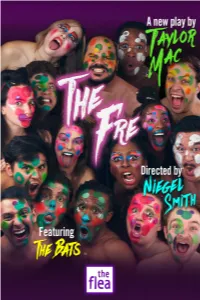

The-Fre-Program-2.Pdf

THE FLEA THEATER NIEGEL SMITH, ARTISTIC DIRECTOR CAROL OSTROW, PRODUCING DIRECTOR PRESENTS THE WORLD PREMIERE OF THE FRE BY TAYLOR MAC DIRECTED BY NIEGEL SMITH FEATURING THE BATS RYAN CHITTAPHONG, GEORGIA KATE COHEN, JON EDWARD COOK, ADAM COY, JOSEPH DALFONSO, NATE DECOOK, URE EGBUHO, JOAN MARIE, ALEX J. MORENO, MARCUS JONES, DRITA KABASHI, MATTHEW MACCA, CESAR MUNOZ, YVONNE JESSICA PRUITT, SARAH ALICE SHULL, LAMBERT TAMIN JIAN JUNG SCENIC DESIGNER MACHINE DAZZLE COSTUME DESIGNER XAVIER PIERCE LIGHTING DESIGNER MATT RAY COMPOSER, MUSIC DIRECTOR & SOUND DESIGNER SARAH EAST JOHNSON CHOREOGRAPHER ADAM J. THOMPSON VIDEO DESIGNER KRISTAN SEEMEL AssOCIATE DIRECTOR SOOA KIM AssOCIATE VIDEO DESIGNER REBECCA APARCIO & SARAH JANE SCHOSTACK AssISTANT DIRECTORS CORI WILLIAMS AssISTANT SCENIC DESIGNER & PROPERTIES DESIGNER HALEY GORDON PRODUCTION STAGE MANAGER CAST Hero............................................Ryan Chittaphong / Lambert Tamin Frankie Fre ..................................... Joseph Dalfonso / Alex J. Moreno Taylor Fre..................................Drita Kabashi / Yvonne Jessica Pruitt Maggie Fre..............................Geogia Kate Cohen / Sarah Alice Shull Bobby Fre (Frankie Fre U/S) ...........................................Nate DeCook Bobby Fre (Hero U/S) .....................................................Cesar Munoz Billy Fre ................................................Jon Edward Cook / Adam Coy Franny Fre ...................................................Ure Egbuho / Joan Marie Brody Fre ..........................................Matthew -

2008 International List of Protected Names

LISTE INTERNATIONALE DES NOMS PROTÉGÉS (également disponible sur notre Site Internet : www.IFHAonline.org) INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (also available on our Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) Fédération Internationale des Autorités Hippiques de Courses au Galop International Federation of Horseracing Authorities _________________________________________________________________________________ _ 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne, France Avril / April 2008 Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org La liste des Noms Protégés comprend les noms : The list of Protected Names includes the names of : ) des gagnants des 33 courses suivantes depuis leur ) the winners of the 33 following races since their création jusqu’en 1995 first running to 1995 inclus : included : Preis der Diana, Deutsches Derby, Preis von Europa (Allemagne/Deutschland) Kentucky Derby, Preakness Stakes, Belmont Stakes, Jockey Club Gold Cup, Breeders’ Cup Turf, Breeders’ Cup Classic (Etats Unis d’Amérique/United States of America) Poule d’Essai des Poulains, Poule d’Essai des Pouliches, Prix du Jockey Club, Prix de Diane, Grand Prix de Paris, Prix Vermeille, Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe (France) 1000 Guineas, 2000 Guineas, Oaks, Derby, Ascot Gold Cup, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth, St Leger, Grand National (Grande Bretagne/Great Britain) Irish 1000 Guineas, 2000 Guineas, Derby, Oaks, Saint Leger (Irlande/Ireland) Premio Regina Elena, Premio Parioli, Derby Italiano, Oaks (Italie/Italia) -

2009 International List of Protected Names

Liste Internationale des Noms Protégés LISTE INTERNATIONALE DES NOMS PROTÉGÉS (également disponible sur notre Site Internet : www.IFHAonline.org) INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (also available on our Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) Fédération Internationale des Autorités Hippiques de Courses au Galop International Federation of Horseracing Authorities __________________________________________________________________________ _ 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne, France Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] 2 03/02/2009 International List of Protected Names Internet : www.IFHAonline.org 3 03/02/2009 Liste Internationale des Noms Protégés La liste des Noms Protégés comprend les noms : The list of Protected Names includes the names of : ) des gagnants des 33 courses suivantes depuis leur ) the winners of the 33 following races since their création jusqu’en 1995 first running to 1995 inclus : included : Preis der Diana, Deutsches Derby, Preis von Europa (Allemagne/Deutschland) Kentucky Derby, Preakness Stakes, Belmont Stakes, Jockey Club Gold Cup, Breeders’ Cup Turf, Breeders’ Cup Classic (Etats Unis d’Amérique/United States of America) Poule d’Essai des Poulains, Poule d’Essai des Pouliches, Prix du Jockey Club, Prix de Diane, Grand Prix de Paris, Prix Vermeille, Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe (France) 1000 Guineas, 2000 Guineas, Oaks, Derby, Ascot Gold Cup, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth, St Leger, Grand National (Grande Bretagne/Great Britain) Irish 1000 Guineas, 2000 Guineas, -

The San Jose Flea Market and the Opportunity Costs of Smart Growth Authors Sean Campion and April Mo

Transit-Oriented Displacement? The San Jose Flea Market and the Opportunity Costs of Smart Growth Authors Sean Campion and April Mo Cover Photos Left photo - Flickr user Canada Good. Right photo - fleaportal.com The Center for Community Innovation (CCI) at UC-Berkeley nurtures effective solutions that expand economic opportunity, diversify housing options, and strengthen connection to place. The Center builds the capacity of nonprofits and government by convening practitioner leaders, providing technical assistance and student interns, interpreting academic research, and developing new research out of practitioner needs. University of California Center for Community Innovation 316 Wurster Hall #1870 Berkeley, CA 94720-1870 http://communityinnovation.berkeley.edu May 2011 Table of Contents Chapter 1: Introduction and Background 1 Chapter 2: Methods 6 Chapter 3: Survey Results and Discussion 8 Chapter 4: Transit Village Market Study 19 Chapter 5: Recommendations and Areas for Further Study 33 Conclusions 36 References 37 Appendix A 40 Appendix B 49 Appendix C 51 Chapter 1: Introduction and Background Photo credit: sfchamber.visitortourist.info.com As California’s population continues to expand and a commercial center over its decades-long lifespan. For places like the Bay Area metropolitan region experience vendors, it has been an entrepreneurial test ground and new development pressures, land use and transportation a small business incubator (Picazo 2009), and it probably planners, economic development agencies and policy has the highest concentration of small businesses in one makers must carefully weigh the economic and location than anywhere else in Silicon Valley (Pizarro 2010). environmental benefits and costs of growth. If we focus And for shoppers, it offers a wide variety of goods and new growth in higher-density developments served by services, including produce, at low – and in some cases public transit, what might be the impacts of such “smart bargainable – prices. -

The Edge of Modernism Kalaidjian, Walter

The Edge of Modernism Kalaidjian, Walter Published by Johns Hopkins University Press Kalaidjian, Walter. The Edge of Modernism: American Poetry and the Traumatic Past. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006. Project MUSE. doi:10.1353/book.60333. https://muse.jhu.edu/. For additional information about this book https://muse.jhu.edu/book/60333 [ Access provided at 25 Sep 2021 02:14 GMT with no institutional affiliation ] This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. FM_7074_Kalaidjian_JHUP 10/21/05 10:20 AM Page i The Edge of Modernism 00_FM_6155_JHUP 3/15/05 10:01 AM Page ii This page intentionally left blank FM_7074_Kalaidjian_JHUP 10/21/05 10:20 AM Page iii The Edge of Modernism American Poetry and the Traumatic Past The Johns Hopkins University Press Baltimore FM_7074_Kalaidjian_JHUP 10/21/05 10:20 AM Page iv © The Johns Hopkins University Press All rights reserved. Published Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper The Johns Hopkins University Press North Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland - www.press.jhu.edu Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Kalaidjian, Walter B., – The edge of modernism : American poetry and the traumatic past / Walter Kalaidjian. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references ( p. ) and index. ISBN --- (hardcover : alk. paper) . American poetry—th century—History and criticism. Literature and history— United States—History—th century. Holocaust, Jewish (–), in literature. Anti-communist movements in literature. Modernism (Literature)—United States. Genocide in literature. Cold War in literature. 8. History in literature. Slavery in literature. I. Title. PS.HK Ј.—dc A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library.