The Rockefeller Institute Review 1963, Vol. 1, No. 3 the Rockefeller University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rockefeller University Revenue Bonds, Series 2019A

Moody’s: Aa1 S&P: AA NEW ISSUE (See “Ratings” herein) $46,770,000 DORMITORY AUTHORITY OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK THE ROCKEFELLER UNIVERSITY REVENUE BONDS SERIES 2019A ® Dated: Date of Delivery Due: July 1, as shown on the inside cover Payment and Security: The Rockefeller University Revenue Bonds, Series 2019A (the “Series 2019A Bonds”) are special limited obligations of the Dormitory Authority of the State of New York (the “Authority” or “DASNY”), payable solely from, and secured by a pledge of (i) certain payments to be made under the Loan Agreement dated as of October 31, 2001, as amended and supplemented, including as proposed to be amended by the Proposed Loan Agreement Amendments (as defined and described herein) (the “Loan Agreement”), between The Rockefeller University (the “University” or “Rockefeller”) and the Authority, and (ii) all funds and accounts (except the Arbitrage Rebate Fund and any fund established for the payment of the Purchase Price of Option Bonds tendered for purchase) established under the Authority’s The Rockefeller University Revenue Bond Resolution, adopted October 31, 2001, as amended (the “Resolution”) and a Series Resolution authorizing the issuance of the Series 2019A Bonds adopted on March 6, 2019 (the “Series 2019A Resolution”). The Loan Agreement is a general, unsecured obligation of the University and requires the University to pay, in addition to the fees and expenses of the Authority and the Trustee, amounts sufficient to pay, when due, the principal, Sinking Fund Installments, if any, Purchase Price and Redemption Price of and interest on all Bonds issued under the Resolution, including the Series 2019A Bonds. -

Marc Tessier-Lavigne, a Leading Neuroscientist He Rockefeller University Campaign Mittee

THE Rockefeller university NEWS FOR BENEFACTORS AND FRIENDS OF THE UNIVERSITY • FALL 2011 MESSAGE FROM DONORS CONTRIBUTE $628 MILLION CHAIRMAN RUSSELL L. CARSON CAMPAIGN FOR COLLABORATIVE SCIENCE EXCEEDS $500 MILLION GOAL The University’s eight-year Campaign for Collaborative Science concluded on June 30, 2011, raising $628 million in new gifts and pledges during the tenure of President Paul Nurse. The Campaign exceeded its $500 mil- lion goal and achieved all that we set out to do, and more. The generosity of our bene- factors was extraordinary. This issue of our newsletter celebrates and acknowledges those whose support is helping to advance Rockefeller’s work. As you read these pages, I hope you take pride in the Campaign’s accomplishments, including our new Collab- orative Research Center on the north campus and the 12 laboratory heads we recruited over the last eight years. The conclusion of our Campaign coincid- ed with a turning point in the University’s history. In the 2010–2011 academic year, we said goodbye to a superb president and welcomed an exceptional scientific leader to Goldberg/Esto Jeff campus as his successor. Paul Nurse became photo: president of the Royal Society in London, and Marc Tessier-Lavigne, a leading neuroscientist he Rockefeller University Campaign mittee. “Because of their commitment and generosity, and the former chief scientific officer of for Collaborative Science has conclud- the future of the University looks brighter than ever.” Genentech, succeeded him in mid-March. In ed, surpassing its $500 million goal Of the $628 million contributed to support the this issue, you will learn more about Marc and with new gifts and grants totaling Campaign, $152 million came in the form of flexible his research program in brain development $628 million. -

Elsa C. Y. Yan Department of Chemistry Yale University 225 Prospect Street, New Haven, CT06511 Tel: (203) 436-2509, Email: Elsa

Elsa C. Y. Yan Department of Chemistry Yale University 225 Prospect Street, New Haven, CT06511 Tel: (203) 436-2509, Email: [email protected] Website: http://ursula.chem.yale.edu/~yanlab/Index.html Education • 2000 Ph.D. (Distinction) Columbia University, New York, NY Advisor: Prof. Kenneth B. Eisenthal Thesis Title: Second Harmonic Generation as a Surface Probe for Colloidal Particles • 1999 M.Phil. Columbia University, New York, NY • 1996 M.A. Columbia University, New York, NY • 1995 B.Sc. (First Class Honors) Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong Professional Appointments 2016- Director of Graduate Studies, Department of Chemistry, Yale University, New Haven, CT 2016- Editor, Biophysical Journal, Cell Press, 2014- Professor of Chemistry, Yale University, New Haven, CT 2012-2014 Associate Professor of Chemistry, Yale University, New Haven, CT 2007-2012 Assistant Professor of Chemistry, Yale University, New Haven, CT 2014- Adjunct Professor, Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong 2010-2014 Adjunct Associate Professor, Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong 2004-2007 Postdoctoral Research Associate, Rockefeller University, New York, NY 2005-2006 Adjunct Assistant Professor, Hunter College, CUNY, New York, NY 2000-2004 Postdoctoral Fellow, UC Berkeley, CA (Mentor: Prof. Richard Mathies) Visiting Fellow, Rockefeller University, New York, NY (Mentor: Prof. Thomas Sakmar) 1995-2000 Research Assistant, Columbia University, New York, NY (Mentor: Prof. Kenneth Eisenthal) Honors and Awards • Elected Chair, Gordon Research Conference: -

Louis Licitra-President Born: Syracuse, New York Education: SUNY Delhi, Syracuse University & Rockefeller University Resident of Bucks County for Over 30 Years

Louis Licitra-President Born: Syracuse, New York Education: SUNY Delhi, Syracuse University & Rockefeller University Resident of Bucks County for over 30 years. Worked with FACT for over 15 years Additionally on the local event planning board for Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS Previous positions include President of the New Hope Chamber of Commerce and board member for over 7 years; event planning board for The Rainbow Room LGBTQA youth group; event planning board for New Hope Celebrates PRIDE (local LGBT organization); Additional support and volunteer work with The New Hope Community Association for high school youth job placement; New Hope Arts member; New Hope Historical Society member; and fund-raising/promotion/volunteer assistance for various organizations throughout the year. Currently, co-owner of Rainbow Assurance, Inc., Title Insurance Agency offering title insurance for PA & NJ. Herb Andrus-Vice President Born: Philadelphia Education: University of Pennsylvania & Pratt Institute, Brooklyn, NY Certifications: Education and Intervention Facilitator (CDC certified.) Worked at Family Sevice Association of Bucks County as Facilitator Lifetime resident of Bucks County Volunteered at --William Way Community Center FACT Board for 3 yrs Boyd Oliver-Treasurer Born: McKeesport PA Graduated Grove City College (PA) with degree in accounting Retired CPA with major public accounting, Fortune 500 corporate and small business experience spanning over 30 years. Has owned and operated his own retail/internet businesses. When not traveling around the globe with his partner, he still enjoys the occasional special consulting assignment or project. Member: AICPA (American Institute Of CPA's) Resident of New Hope/Solebury, Bucks County for over 20 years Tim Philpot-Secretary On the board of FACT for two years and served as secretary for the past year. -

Elizabeth a Heller Phd [email protected] | 215.523.7038

Elizabeth A Heller PhD [email protected] | 215.523.7038 Education 2009 PhD Molecular Biology The Rockefeller University, New York, NY, USA 2002 BA Biology, magna cum laude University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA USA 1998 Diploma, honors in biology Stuyvesant High School, New York, NY USA Research 2016 - Assistant Professor, Department of Pharmacology and positions present Program in Epigenetics The University of Pennsylvania. Philadelphia, PA 2010- Postdoctoral Associate, Department of Neuroscience 2015 Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY. Advisor: Eric J Nestler MD PhD 2003- Graduate Student, Laboratory of Molecular Biology 2009 The Rockefeller University, New York, NY. Advisor: Nathaniel Heintz PhD 1999- Undergraduate Thesis Research. Department of Biology 2002 University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. Advisor: Ted Abel PhD 2000 Summer Research Student, Center for Neural Science New York University, New York, NY. Advisors: Joseph LeDoux PhD and Raphael Lamprecht PhD 1994- Westinghouse Research, Public Health Research Institute, New York, NY. 1998 Advisor: Barry Kreiswirth PhD Awards & 2016 Whitehall Foundation Research Grant Honors 2016 Charles E Kaufman Foundation Early Investigator Grant 2016 NARSAD Young Investigator Award 2015 Robin Chemers Neustein Postdoctoral Fellowship 2014 Keystone Symposia Scholarship, Neuroepigenetics 2013 NIDA Director’s Travel Award 2013 NIDA Individual National Research Service Award 2013 Icahn School of Medicine Postdoc Appreciation Award 2013 American College of Neuropsychopharm. Travel Award 2012 NIDA Institutional National Research Service Award 2003 Women & Science Fellowship, The Rockefeller University 2002 Phi Beta Kappa Honors Society Membership 2001 Barry M Goldwater Scholarship nominee 1998 2nd Place, St. John’s University Metro NY Science Fair 1998 Honorable mention, NYC Intl. -

Summer Camp Song Book

Summer Camp Song Book 05-209-03/2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Numbers 3 Short Neck Buzzards ..................................................................... 1 18 Wheels .............................................................................................. 2 A A Ram Sam Sam .................................................................................. 2 Ah Ta Ka Ta Nu Va .............................................................................. 3 Alive, Alert, Awake .............................................................................. 3 All You Et-A ........................................................................................... 3 Alligator is My Friend ......................................................................... 4 Aloutte ................................................................................................... 5 Aouettesky ........................................................................................... 5 Animal Fair ........................................................................................... 6 Annabelle ............................................................................................. 6 Ants Go Marching .............................................................................. 6 Around the World ............................................................................... 7 Auntie Monica ..................................................................................... 8 Austrian Went Yodeling ................................................................. -

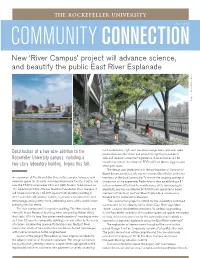

'River Campus' Project Will Advance Science

FALL 2015 COMMUNITY CONNECTION New ‘River Campus’ project will advance science, and beautify the public East River Esplanade Image from Rafael Viñoly Architects Image from Rafael Viñoly such as benches, high- and low-back lounge seats, and seat walls Construction of a two-acre addition to the located to maximize views; and pedestrian lighting to provide a Rockefeller University campus, including a safe and renewed waterfront experience. A noise barrier will be installed to reduce the impact of FDR traffic on bikers, joggers, and two-story laboratory building, begins this fall. other park users. The design was developed with the participation of Community Board 8 representatives, city council member Ben Kallos, and other An expansion of The Rockefeller University’s campus, to house new members of the local community. To ensure the ongoing upkeep of research space for its world-renowned bioscience faculty, is set to rise this portion of the esplanade, Rockefeller is also establishing a $1 over the FDR Drive between 64th and 68th Streets. To be known as million endowment to fund the maintenance of its landscaping in The David Rockefeller–Stavros Niarchos Foundation River Campus, it perpetuity, and has contributed $150,000 and appointed a board will house a two-story, 135,600 square-foot laboratory building in member to Friends of the East River Esplanade, a conservancy which scientists will conduct studies in genomics, neuroscience, and devoted to the esplanade restoration. immunology, among other fields, addressing some of the world’s most “This construction project is critical for the university’s continued pressing medical needs. -

FMC Flea and Farmers Market Study Appendix

French Market Flea & Farmers Market Study Appendix This appendix includes all of the documents produced during the engagement and study process for the French Market. Round 1 Engagement Summary Round 2 Engagement Summary ROUND 1 STAKEHOLDER ROUND 2 STAKEHOLDER ENGAGEMENT SUMMARY ENGAGEMENT SUMMARY Vendor Meeting Jan. 21, 8-10 AM Public Virtual Meeting Public Virtual Meeting February 25, 6-7 PM Jan. 21, 6-8 PM Public Survey Culture Bearer Meeting February 25 - March 12 Feb. 11, 12-1 PM Round 3 Engagement Summary Public Bathing Research Document Round 3 Stakeholder ADDENDUM: PUBLIC TOILETS AND SHOWERS Engagement Takeaways Bathrooms at the French Market Stakeholders offered the following feedback after reviewing preliminary recommendations for each category: Findings about plumbing, public toilets and showers Policy Research findings: • Provide increased support for janitorial staff and regular, deep cleaning of bathrooms and facilities • Estate clear policies and coordination needed for vendor loading and parking An initial search into public hygiene facilities has yielded various structures • Incentivize local artists to be vendors by offering rent subsidies for local artist and artisan vendors who hand-make their products. and operating models, all of which present opportunities for addressing • Designate a specific area for local handmade crafts in the market, that is separate from other products so the FMC’s desire to support its vendors, customers, and the surrounding community. customers know where to find them. • Vendor management software and apps work for younger vendors but older vendors should be able to Cities, towns, municipalities and non-profit organizations, alone and in partnership, have access the same information by calling or talking to FMC staff in person. -

Hugh C. Hemmings, Jr., MD., Phd As Chairman of the Department Of

Hugh C. Hemmings, Jr., MD., PhD As Chairman of the Department of Anesthesiology, Dr. Hemmings oversees the extensive clinical and basic anesthesiology research program in the department. He has authored over 100 publications including a textbook on basic anesthesiology. His clinical practice focuses on anesthesia for thoracic surgery and other high risk procedures. He leads an active research group investigating the neuropharmacology of general anesthetics, neuroprotection, cell signaling and novel analgesia therapies. A summary of education, training and/or faculty appointments is listed as following: 2018-present Senior Associate Dean for Research 2013-present Chairman and Anesthesiologist-in-Chief, Department of Anesthesiology, Weill Cornell Medical College 2001-present Professor of Pharmacology, Weill Medical College of Cornell University, New York, NY 2000-present Adjunct Faculty, Laboratory of Molecular and Cellular Neuroscience, The Rockefeller University, New York, NY 2000-present Attending Anesthesiologist, Weill Medical College of Cornell University, New York, NY 2000-present Professor of Anesthesiology, Weill Medical College of Cornell University, New York, NY 1999-present Vice Chair for Research, Department of Anesthesiology, Weill Medical College of Cornell University, New York, NY 1998-2001 Associate Professor of Pharmacology, Weill Medical College of Cornell University, New York, NY 1996-2000 Associate Attending Anesthesiologist, The New York Hospital, New York, NY 1996-2000 Associate Professor of Anesthesiology, Cornell -

![Elegant Molecules: [Dr. Stanford Moore] Fulvio Bardossi](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2843/elegant-molecules-dr-stanford-moore-fulvio-bardossi-1792843.webp)

Elegant Molecules: [Dr. Stanford Moore] Fulvio Bardossi

Rockefeller University Digital Commons @ RU Rockefeller University Research Profiles Campus Publications Spring 1982 Elegant Molecules: [Dr. Stanford Moore] Fulvio Bardossi Judith N. Schwartz Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.rockefeller.edu/research_profiles Part of the Life Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Bardossi, Fulvio and Schwartz, Judith N., "Elegant Molecules: [Dr. Stanford Moore]" (1982). Rockefeller University Research Profiles. Book 13. http://digitalcommons.rockefeller.edu/research_profiles/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Campus Publications at Digital Commons @ RU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Rockefeller University Research Profiles by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ RU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Carbo I Leu ------Asn--------.....) THE ROCKEFELLER UNIVERSITY I 18 _ C,.---------~~----.-- ....---_...980....101_------~ His (P'o) ~-----------His--- ...../IIB RESEARCH 131 170 s 5 Diagram ofspecial pllDOIi\1CIIES features ofbovine 206 N J.L pancreatic deoxyribonuclease. ......------------Thr SPRING 1982 257 Elegant Molecules Asked how he happened to become a biochemist, Professor FROM THE GREEKPROTEIOS: Stanford Moore attributes the choice to gifted teachers of PRIMARY science and a vocational counselor who advised him that there was no future in aeronautical engineering. "But," he adds Proteins comprise the largest part of the solid mattel ofliving with a smile, ''I've never regretted the choice. I can imagine cells. Some proteins, such as the hemoglobin that carries oxy no life more fascinating or more rewarding than one spent gen in red blood cells, are involved in transport and stOrage. exploring the elegant and complicated architecture of organic Many hormones, like insulin, are proteins; they are chemical molecules." messengers that coordinate body activities. -

Why a University for Chicago and Not Cleveland? Religion and John D

Why a University For Chicago And Not Cleveland? Religion And John D. Rockefeller’s Early Philanthropy, 1855-1900 Kenneth W. Rose Assistant to the Director Rockefeller Archive Center ____________________ © 1995. This essay is a revised version of a paper prepared for the Western Reserve Studies Symposium in Cleveland, Ohio, October 6-7, 1995, and included in From All Sides: Philanthropy in the Western Reserve. Papers, Abstracts, and Program of the Tenth Annual Western Reserve Studies Symposium, sponsored by the Case Western Reserve University American Studies Program. (Cleveland: Case Western Reserve University, 1995), pp. 30-41. The author welcomes the scholarly use of the ideas and information in this essay, provided that the users properly acknowledge the source and notify the author of such citation at [email protected]. ____________________ Clevelanders sometimes seem to have a “What have you done for me lately?” attitude with regard to John D. Rockefeller. As if the creation on the Cuyahoga’s shores of one of the country’s most powerful and influential corporations is not enough, some Clevelanders look to Rockefeller’s enormous charitable giving and wonder why he built no major institution in Cleveland to provide jobs and world renown under the Rockefeller banner. Most people who express such opinions often point, with a hint of jealousy, to the University of Chicago as an example of Cleveland’s missing Rockefeller landmark. To believe that a Rockefeller-endowed University of Cleveland would today have the same academic and intellectual reputation as the present-day University of Chicago, one must assume that the same personalities and forces that shaped the University of Chicago would have been present in Cleveland, and that they would have behaved and acted exactly the same way in this different environment. -

Convocation for Conferring Degrees Virtual Ceremony Thursday, June 11, 2020 Academic Procession New Castle Brass Quintet Welcomi

Convocation for Conferring Degrees Virtual Ceremony Thursday, June 11, 2020 Academic Procession New Castle Brass Quintet Welcoming Remarks Richard P. Lifton, M.D., Ph.D. President and Carson Family Professor Introduction Sidney Strickland, Ph.D. Dean of Graduate and Postgraduate Studies Vice President for Educational Affairs Conferring of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dr. Lifton Presentation of the David Rockefeller Award for Extraordinary Service Dr. Lifton Alzatta Fogg Torsten N. Wiesel, M.D., F.R.S. Conferring of the Degree of Doctor of Science, Honoris Causa Dr. Lifton Marnie S. Pillsbury Lucy Shapiro, Ph.D. Academic Recession New Castle Brass Quintet 2 2020 Graduates Sarah Ackerman B.S., State University of New York, College at Geneseo The Role of Adipocytes in the Tumor Microenvironment in Obesity-driven Breast Cancer Progression Paul Cohen Sarah Kathleen Baker B.A., University of San Diego Blood-derived Plasminogen Modulates the Neuroimmune Response in Both Alzheimer’s Disease and Systemic Infection Models Sidney Strickland Mariel Bartley B.Sc., Monash University Characterizing the RNA Editing Specificity of ADAR Isoforms and Deaminase Domains in vitro Charles M. Rice Kate Bredbenner B.S., B.A., University of Rochester Visualizing Protease Activation, retroCHMP3 Activity, and Vpr Recruitment During HIV-1 Assembly Sanford M. Simon Ian Andrew Eckardt Butler B.A., The University of Chicago Hybridization in Ants Daniel Kronauer Daniel Alberto Cabrera* B.A., Columbia University Time-restricted Feeding Extends Longevity in Drosophila melanogaster Michael W. Young * Participant in the Tri-Institutional M.D.-Ph.D. Program 3 James Chen B.A., University of Pennsylvania Cryo-EM Studies of Bacterial RNA Polymerase Seth A.