TOCC0463DIGIBKLT.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“The Soul of Ukraine” International Support Foundation for Ukrainian Nation

“THE SOUL OF UKRAINE” INTERNATIONAL SUPPORT FOUNDATION FOR UKRAINIAN NATION Press release 3 June 2014 An International Foundation for the support of Ukrainian people, under the official patronage of His Holiness Patriarch of Kyiv and All Rus'-Ukraine Filaret, was organized by world celebrities. June 3, 2014 Ministry of Justice of Ukraine registered “The Soul of Ukraine” Foundation. The Chairman of the foundation's Board of Trustees is Borys Paton – Hero of Ukraine (first), President of the National Academy of Science of Ukraine. At the same time Academician Paton is the President of the International Association of Academies of Science. The Co-Chairmans of the foundation's Board of Trustees are Reverend Agapit – Bishop of Vyshgorod, Kyivan Patriarchate Administrator and Vicar of St. Michael's Monastery, and People's Artist of Ukraine Myroslav Vantuh – world legend of dance art, Hero of Ukraine, Academician, People's Artist of Ukraine and Russia, General Manager and Artistic Director of Pavlo Virsky Ukrainian National Folk Dance Ensemble. The Members of the foundation's Board of Trustees from Ukraine are known figures of Ukrainian culture. Hero of Ukraine and Academician Anatoliy Andrievskiy – is Manager and Artistic Director of H.Veryovka Ukrainian National Folk Chorus and President of the Ukrainian National Music Committee of UNESCO International Music Council. Academician Borys Olijnyk – Hero of Ukraine, Ukrainian Culture Fund Chairman. Hero of Ukraine, People's Artist of Ukraine, Corresponding Member of Ukrainian National Academy of Arts Evgen Savchuk – Artistic Director of National Academic Choir of Ukraine “Dumka”. Academician, Hero of Ukraine, People's Artist of Ukraine Eugene Stankovych – is Department Head of Tchaikovsky National Music Academy of Ukraine. -

Myroslav Skoryk (B

Myroslav SSKKOORRYYKK VViioolliinn CCoonncceerrttooss •• 22 NNooss.. 55––99 AAnnddrreejj BBiieellooww,, VViioolliinn NNaattiioonnaall SSyymmpphhoonnyy OOrrcchheessttrraa ooff UUkkrraaiinnee VVoollooddyymmyyrr SSiirreennkkoo Myroslav Skoryk (b. 1938) Violin Concertos • 2 2 4 numerous concertos, including nine for violin, three for Concerto No. 6 (2009) Concerto No . 8 ‘ Allusion to Chopin ’ (2011) piano, two for cello, one for viola and one for oboe, as well Moderato Andante as six partitas for various instrumental configurations. His output also includes solo instrumental works and music First performance: Kyiv; dedicated to the first performer First performance: Kyiv; dedicated to the first performer for films such as Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors and Andrej Bielow; conductor Mykola Dyadyura. Katharina Fejer; conductor Myroslav Skoryk. The High Pass , and numerous animated cartoons. Skoryk’s works are performed in the Ukraine and The two main themes of the concerto characterise the This work was written to mark the 200th anniversary of throughout the world, such as Canada, Australia, the US, composer’s craving for sensual, delicate and fragile Fryderyk Chopin’s birth and can be seen as homage to Japan, China, and in most European countries. moods. Yet they are contrasted by episodes that violate the Polish virtuoso. It uses ‘quotations’ from his various One of his most popular pieces is Melody in A minor , their lyrical mood: marching melodies, provocative piano works – Préludes , Mazurkas and Sonatas . These which he often performs as a conductor and pianist. dances, rapid expressive fugato based on the sonorous are combined with Skoryk’s own ‘voice’ in an imitation of 1 dialogue between the violin and other instruments in the Chopin's style. -

Symphonic Dances

ADELAIDE SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA SEASON 2019 MASTER SERIES 6 Symphonic Dances August Fri 16, 8pm Sat 17, 6.30pm PRESENTING PARTNER Adelaide Town Hall 2 MASTER SERIES 6 Symphonic Dances August Dalia Stasevska Conductor Fri 16, 8pm Louis Lortie Piano Sat 17, 6.30pm Adelaide Town Hall John Adams The Chairman Dances: Foxtrot for Orchestra Ravel Piano Concerto in G Allegramente Adagio assai Presto Louis Lortie Piano Interval Rachmaninov Symphonic Dances, Op.45 Non allegro Andante con moto (Tempo di valse) Lento assai - Allegro vivace Duration Listen Later This concert runs for approximately 1 hour This concert will be recorded for delayed and 50 minutes, including 20 minute interval. broadcast on ABC Classic. You can hear it again at 2pm, 25 Aug, and at 11am, 9 Nov. Classical Conversation One hour prior to Master Series concerts in the Meeting Hall. Join ASO Principal Cello Simon Cobcroft and ASO Double Bassist Belinda Kendall-Smith as they connect the musical worlds of John Adams, Ravel and Rachmaninov. The ASO acknowledges the Traditional Custodians of the lands on which we live, learn and work. We pay our respects to the Kaurna people of the Adelaide Plains and all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Elders, past, present and future. 3 Vincent Ciccarello Managing Director Good evening and welcome to tonight’s Notwithstanding our concertmaster, concert which marks the ASO debut women are significantly underrepresented of Finnish-Ukrainian conductor, in leadership positions in the orchestra. Dalia Stasevska. Things may be changing but there is still much work to do. Ms Stasevska is one of a growing number of young women conductors Girls and women are finally able to who are making a huge impression consider a career as a professional on the international orchestra scene. -

Jonathan Roozeman's Biography

Jonathan Roozeman, violonchelo “Jonathan Roozeman proved a virtuoso” New York Times Finnish-Dutch cellist and rising star, Jonathan Roozeman is already establishing himself as a player of exceptional musical integrity. His phenomenal, expansive and versatile sound lends itself not only to works of the core classical repertory, but those by Kabalevsky, Kokkonen, Vieuxtemps and Sallinen. He has been recognized by top conductors including Valery Gergiev, Sakari Oramo, Esa-Pekka Salonen, Osmo Vänskä, Dima Slobodeniouk, Jukka-Pekka Saraste and Santtu-Matias Rouvali, and been invited by leading orchestras including: The Mariinsky Orchestra, St Petersburg Philharmonic Orchestra, and Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra. Engagements in 2019/20 include: a return to the Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra under Esa-Pekka Salonen, hr- Sinfonieorchester with Christoph Eschenbach, Orquesta Sinfonica de Euskadi conducted by Edo de Waart, Tampere Philharmonic, Gulbenkian Orchestra, Polish National Radio Symphony, and a performance of Alexey Shor’s Cello Concerto with the Armenian State Symphony Orchestra. Jonathan will return to the Ark Hills Festival in Tokyo which will include chamber performances with Fumiaki Miura and Nobuyuki Tsujii and a collaboration with Fumiaki Miura and Varvara in Spain. He will also appear at the Baroque on the Edge Festival in London together with bass guitarist, Lauri Porra, presenting their ‘Bach Reimagined’ project. Highlights in previous seasons include; his debut with the BBC Symphony Orchestra under Dalia Stasevska, a return to the White Nights Festival and appearances in Schloss Elmau as part of the Verbier Festival Residency for a recital and performance of the rarely performed Monn Cello Concerto in G Minor. Other engagements have included dates with the Japan Philharmonic Orchestra and Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra, Tapiola Sinfonietta, China National Symphony Orchestra and a debut recital tour in Canada which included the prestigious Vancouver Recital Series. -

University of California UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Ukrainian Identity in Modern Chamber Music: A Performer's Perspective on Valentyn Silvestrov's Violin Sonata "Post Scriptum" and its Interpretation in the Context of Ukrainian Chamber Works. Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8874s0pn Author Khomik, Myroslava Publication Date 2014 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Ukrainian Identity in Modern Chamber Music: A Performer’s Perspective on Valentyn Silvestrov’s Violin Sonata “Post Scriptum” and its Interpretation in the Context of Ukrainian Chamber Works A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction Of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Musical Arts By Myroslava Khomik 2015 © Copyright by Myroslava Khomik 2015 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Ukrainian Identity in Modern Chamber Music: A Performer’s Perspective on Valentyn Silvestrov’s Violin Sonata “Post Scriptum” and its Interpretation in the Context of Ukrainian Chamber Works. by Myroslava Khomik Doctor of Musical Arts University of California, Los Angeles, 2015 Professor Movses Pogossian, Chair Ukrainian cultural expression has gone through many years of inertia due to decades of Soviet repression and censorship. In the post-Soviet period, since the late 80s and early 90s, a number of composers have explored new directions in creative styles thanks to new political and cultural freedoms. This study focuses on Valentyn Silvestrov’s unique Sonata for Violin and Piano “Post Scriptum” (1990), investigating its musical details and their meaning in its post- Soviet compositional context. The purpose is to contribute to a broader overview of Ukraine’s classical music tradition, especially as it relates to national identity and the ii current cultural and political state of the country. -

38 September 21, 2003

INSIDE:• National Rukh of Ukraine marks anniversary — page 3. • Third Youth Leadership Program held in D.C. — page 9. • Ukrainian named top female wrestler — page 11. Published by the Ukrainian National Association Inc., a fraternal non-profit association Vol. LXXI HE No.KRAINIAN 38 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 21, 2003 EEKLY$1/$2 in Ukraine T U With reservations,W Cabinet and Rada approve Embassy of Russia works against Ukraine’s entry into common economic space SenateWASHINGTON resolution – The Embassy ofonUkraine Famine-Genocide of the 1930s.” by Roman Woronowycz ment’s decision on what it wants to do with Russia in the United States has voiced its He continued: “Many aspects of the Kyiv Press Bureau the united economic space, but I think there opposition to a Senate resolution that rec- realization of the policies of the Soviet needs to be a careful look at how this ognizes the Great Famine of 1932-1933 in leadership of that time headed by Stalin KYIV – Ukraine’s Cabinet of Ministers agreement fits in with the country’s aspira- Ukraine as genocide. were tragic for many peoples on the terri- and Verkhovna Rada pushed through sepa- tions to join the Euro-Atlantic community,” Radio Liberty reported last week that tory of the USSR, not only for Ukrainians, rate documents on September 17 in support explained Ambassador Herbst. “I believe it sources said Russian officials have con- but also for Russians, Estonians, of the country’s entry into a common mar- is in the interest of Ukraine not to take any tacted officials at the U.S. -

NEXTET the New Music Ensemble for the 21St Century Virko Baley, Music Director and Conductor Chris Arrell, Composer-In-Residence

Department of MUSIC College of Fine Arts presents NEXTET The New Music Ensemble for the 21st Century Virko Baley, music director and conductor Chris Arrell, composer-in-residence PROGRAM Maxwell R. Lafontant Healing Waters (2013) (b. 1990) r-Jextet Ensemble Britta Epling From dewy dreams (2013) (b. 1992) Britta Epling, soprano Virko Baley , piano Enzu Chang Sketch for unaccompanied oboe (2013) (b.1981) Ben Serna-Grey, oboe Chris Arrell Mutations (2013) for violoncello and computer (b. 1970) Andrew Smith, violoncello Chris Arrell, computer Boris Lyatoshynsky Sonata-Ballade, Op. 18 (1925) (1895-1968) Valentin Silvestrov Sonata No. 3 (1979/ rev.1999) (b. 1937) Preludio Fuga Postludio Timothy Haft, piano Virko Baley From Holodomor (Red Earth. Hunger) (b. 1938) "Black wounds, on the palm of the earth" Tod Fitzpatrick, baritone Virko Baley, piano Christopher Gainey The Selfish Giant for flute and storyteller (1988) (b.1981) (with text adapted from "The Selfish Giant" by Oscar Wilde) Expulsion from the Garden Dances of Eternal Winter The Return of Spring Anastasia Patanova, flute Tod Fitzpatrick, narrator Chris Arrell Of Three Minds (2013) for soprano, piano, and computer Texts from Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird by Wallace Stevens · Michelle Latour, soprano Timothy Haft, piano Chris Arrell, computer Tuesday,December10, 2013 7:30 p.m. Dr. Arturo Rando-Grillot Recital Hall Lee and Thomas Beam Music Center University of Nevada, Las Vegas PROGRAM NOTES AND BIOGRAPHIES Chris Arrell (b. 1970, Portland, Oregon) writes music for voices, instruments, and electronics. Praised for their unconventional beauty by The Boston Music Intelligencer and hailed as "sensuous" and "highly nuanced" by the Atlanta Journal Constitution, his compositions explore counterpoints of process woven from the interplay of color, line , and harmony. -

Toimintakertomus 2018 Sisällys

TOIMINTAKERTOMUS 2018 SISÄLLYS UUDESTA JA VANHASTA MAAILMASTA .......... 3 TOIMINTA LUKUINA ....................................... 7 LEVYTYS-, TALTIOINTI- JA KUVATUOTANTO ............................................ 8 OSALLISTAVA TAITEELLINEN TOIMINTA ....... 10 MARKKINOINTIVIESTINTÄ ............................ 12 HENKILÖSTÖ JA HALLINTO .......................... 14 KONSERTIT / KEVÄTKAUSI 2018 .................. 20 KONSERTIT / SYYSKAUSI 2018 .................... 26 LEVYTYKSET 1984-2018 .............................. 36 KANSAINVÄLISET KONSERTTIKIERTUEET 1900-2018 .............. 40 © MAARIT KYTÖHARJU 2 UUDESTA JA VANHASTA MAAILMASTA Helsingin kaupunginorkesterin toimintavuosi 2018 jatkui edellisenä syksynä alkaneen teeman eli saksalaisen kielialueen musiikin parissa. Ohjelmiston aikajana ulottui Beethovenin, Mahlerin ja Brucknerin klassikkosävellysten kautta oman aikamme musiikkiin. Kevään 2018 aikana Musiikkitalon lavalle yhdessä kaupunginorkesterin kanssa nousivat mm. kapellimestari Juraj Valcuha, sopraano Karita Mattila, pianisti Beatrice Rana, sellisti Nicolas Altstaedt ja Sibelius- viulukilpailun voittanut Christel Lee. Kevätkaudella oli tarjolla erikoisprojekti myös lapsiyleisölle. Tarinallisessa konsertissa soivat Iiro Rantalan uudet sävellykset Timo Parvelan Ella ja kaverit konsertissa -kirjaan. Kustannusosakeyhtiö Tammen julkaisemassa kirjassa oli mukana HKO:n levyttämä Ella- albumi. Kevätkausi huipentui Salzburgiin ja Pariisiin suuntautuneeseen konserttikiertueeseen toukokuussa 2018. Orkesteri konsertoi kolmesti Salzburgin Grosses -

Focus on Tobias Broström & Esa Pietilä

NORDIC HIGHLIGHTS 2/2019 NEWSLETTER FROM GEHRMANS MUSIKFÖRLAG & FENNICA GEHRMAN Focus on Tobias Broström & Esa Pietilä NEWS Ten performances of the Moomin Opera Flash Flash available at Yle Areena Th ere will be ten performances of the Moomin Maarit Kytöharju Photo: Opera by Ilkka Kuusisto in September: in Tam- Juhani Nuorvala’s opera Flash Flash – Two pere on 13–15 and Valkeakoski on 21–29. Th e Deaths of Andy Warhol is now at Yle Aree- opera is based on the book Vaarallinen juhannus na and available also to viewers outside (Moominsummer Madness) by Tove Jansson, in Finland. Th is opera to a text in English by which the Moomins take refuge from the fl ood Juha Siltanen has enjoyed cult status on in an opera house fl oating by. Th e project is a the Finnish opera scene; it is seductively joint Tampere Music Academy and Valkeakoski melodious, pop-infl ected, absurd and thrill- City Th eatre production. Also taking part in ing – something quite unique. Flash Flash the performance conducted by Tuomas Turria- was premiered on 9 February and received four additional performances at Espoo City go will be students and young actors from the Th eatre in May. Th e soloists were Tuu- Valkeakoski Music Institute and Th eatre School. li Lindeberg, David Hackston, Martti Anttila, Sampo Haapaniemi and Varvara Collections for saxophone Merras-Häyrynen. Tap dancer Ari Kaup- and clarinet pila performed a stunning scene at the end. Kalevi Aho premieres Th e BBC commissioned a work from Kalevi Aho as part of a set entitled Pictures Within: Birthday Variations for M.C.B. -

Concert Program

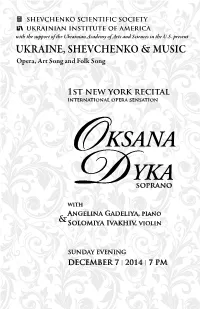

Oksana Dyka, soprano Angelina Gadeliya, piano • Solomiya Ivakhiv, violin I. Bellini Vincenzo Bellini Casta Diva (1801-1835) from Norma (1831) Program Mozart Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Porgi, amor, qualche ristoro (1756-1791) from The Marriage of Figaro (1786) Rossini Gioachino Rossini Selva opaca, Recitative and Aria (1792-1868) from Guglielmo Tell (William Tell, 1829) Ms. Dyka • Ms. Gadeliya II. Shchetynsky Alexander Shchetynsky An Episode in the Life of the Poet, (b. 1960) an afterword to the opera Interrupted Letter (2014) World Premiere Ms. Ivakhiv • Ms. Gadeliya III. From Poetry to Art Songs 1: Settings of poems by Taras Shevchenko Shtoharenko Andriy Shtoharenko Yakby meni cherevyky (1902-1992) (If I had a pair of shoes, 1939) Silvestrov Valentin Silvestrov Proshchai svite (b. 1937) (Farewell world, from Quiet Songs, 1976) Shamo Ihor Shamo Zakuvala zozulen’ka (1925-1982) (A cuckoo in a verdant grove, 1958) Skoryk Myroslav Skoryk Zatsvila v dolyni (b. 1938) (A guelder-rose burst into bloom, 1962) Mussorgsky Modest Mussorgsky Hopak (1839-1881) from the opera Sorochynsky Fair (1880) Ms. Dyka • Ms. Gadeliya 2 Program — INTERMISSION — I V. Beethoven Ludwig van Beethoven Allegro vivace (1770-1827) from Sonata in G Major, Op. 30 (1801-1802) Vieuxtemps Henri Vieuxtemps Désespoir (1820-1881) from Romances sans paroles, Op. 7, No. 2 (c.1845) Ms. Ivakhiv • Ms. Gadeliya V. From Poetry to Art Songs 2: Settings of poems by Taras Shevchenko Lysenko Mykola Lysenko Oy, odna ya odna (1842-1912) (I’m alone, so alone, 1882) Rachmaninov Sergei Rachmaninov Poliubila ya na pechal’ svoyu, (1873-1943) Op. 8, No. 4 (I have given my love, 1893) Stetsenko Kyrylo Stetsenko Plavai, plavai, lebedon’ko (1882-1922) (Swim on, swim on, dear swan, 1903) Dankevych Konstantyn Dankevych Halia’s Aria (1905-1984) from the opera Nazar Stodolia (1960) VI. -

Cornerstones of the Ukrainian Violin Repertoire 1870 – Present Day

Cornerstones of the Ukrainian violin repertoire 1870 – present day Carissa Klopoushak Schulich School of Music McGill University Montreal, Quebec January 2013 A doctoral paper submitted to McGill University in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Music in Performance Studies © Carissa Klopoushak 2013 i Abstract: The unique violin repertoire by Ukrainian composers is largely unknown to the rest of the world. Despite cultural and political oppression, Ukraine experienced periods of artistic flurry, notably in the 1920s and the post-Khrushchev “Thaw” of the 1960s. During these exciting and experimental times, a greater number of substantial works for violin began to appear. The purpose of the paper is one of recovery, showcasing the cornerstone works of the Ukrainian violin repertoire. An exhaustive history of this repertoire does not yet exist in any language; this is the first resource in English on the topic. This paper aims to fill a void in current scholarship by recovering this substantial but neglected body of works for the violin, through detailed discussion and analysis of selected foundational works of the Ukrainian violin repertoire. Focusing on Maxym Berezovs´kyj, Mykola Lysenko, Borys Lyatoshyns´kyj, Valentyn Sil´vestrov, and Myroslav Skoryk, I will discuss each composer's life, oeuvre at large, and influences, followed by an in-depth discussion of his specific cornerstone work or works. I will also include cultural, musicological, and political context when applicable. Each chapter will conclude with a discussion of the reception history of the work or works in question and the influence of the composer on the development of violin writing in Ukraine. -

TOCC0443DIGIBKLT.Pdf

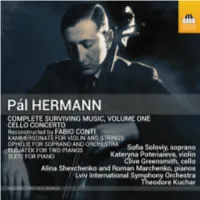

THE REDISCOVERY OF PÁL HERMANN by Robert J. Elias For most of music history, the musical hyphenate ‘performer-composer’ was the rule rather than the exception – but the hyphen seems to sit atop a fulcrum, and it tips this way or that over time. Gustav Mahler was known primarily as a conductor in his day. Other than contemporaneous reports of Mahler’s brilliance as a conductor, there is no ‘hard’ evidence – such as recordings – of his performances. By contrast, archival film of Richard Strauss and Igor Stravinsky on the podium makes clear that their conducting prowess lagged far behind their compositional skills. The tipping point toward specialisation came with the arrival of recorded sound, and was solidified during the era of the long-play recording, from the 1950s onwards. As classical musicians took on the role of celebrities – sometimes reluctantly – record- company executives urged them to nurture their roles as celebrity performers rather than confuse the public with too many versions of their ‘brands’. Before long, the wide availability of recorded music, both historical and contemporary, along with the growing importance and dissemination of critical reviews, also caused many active performer-composers to slip their own original works shyly into a drawer, taking them out only occasionally and, often, only in private settings. Pál (Paul) Hermann was a typical performer-composer of his time. Reviews of his performances suggest that he was a superb cellist during the 1920s and ’30s – a busy chamber musician, with occasional solo opportunities. When he could, he also taught, though maintaining a serious teaching studio required a more stable schedule – and more stable politics – than was ultimately possible.