EEFI 2020-2021 Moot Problem

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“The Soul of Ukraine” International Support Foundation for Ukrainian Nation

“THE SOUL OF UKRAINE” INTERNATIONAL SUPPORT FOUNDATION FOR UKRAINIAN NATION Press release 3 June 2014 An International Foundation for the support of Ukrainian people, under the official patronage of His Holiness Patriarch of Kyiv and All Rus'-Ukraine Filaret, was organized by world celebrities. June 3, 2014 Ministry of Justice of Ukraine registered “The Soul of Ukraine” Foundation. The Chairman of the foundation's Board of Trustees is Borys Paton – Hero of Ukraine (first), President of the National Academy of Science of Ukraine. At the same time Academician Paton is the President of the International Association of Academies of Science. The Co-Chairmans of the foundation's Board of Trustees are Reverend Agapit – Bishop of Vyshgorod, Kyivan Patriarchate Administrator and Vicar of St. Michael's Monastery, and People's Artist of Ukraine Myroslav Vantuh – world legend of dance art, Hero of Ukraine, Academician, People's Artist of Ukraine and Russia, General Manager and Artistic Director of Pavlo Virsky Ukrainian National Folk Dance Ensemble. The Members of the foundation's Board of Trustees from Ukraine are known figures of Ukrainian culture. Hero of Ukraine and Academician Anatoliy Andrievskiy – is Manager and Artistic Director of H.Veryovka Ukrainian National Folk Chorus and President of the Ukrainian National Music Committee of UNESCO International Music Council. Academician Borys Olijnyk – Hero of Ukraine, Ukrainian Culture Fund Chairman. Hero of Ukraine, People's Artist of Ukraine, Corresponding Member of Ukrainian National Academy of Arts Evgen Savchuk – Artistic Director of National Academic Choir of Ukraine “Dumka”. Academician, Hero of Ukraine, People's Artist of Ukraine Eugene Stankovych – is Department Head of Tchaikovsky National Music Academy of Ukraine. -

Myroslav Skoryk (B

Myroslav SSKKOORRYYKK VViioolliinn CCoonncceerrttooss •• 22 NNooss.. 55––99 AAnnddrreejj BBiieellooww,, VViioolliinn NNaattiioonnaall SSyymmpphhoonnyy OOrrcchheessttrraa ooff UUkkrraaiinnee VVoollooddyymmyyrr SSiirreennkkoo Myroslav Skoryk (b. 1938) Violin Concertos • 2 2 4 numerous concertos, including nine for violin, three for Concerto No. 6 (2009) Concerto No . 8 ‘ Allusion to Chopin ’ (2011) piano, two for cello, one for viola and one for oboe, as well Moderato Andante as six partitas for various instrumental configurations. His output also includes solo instrumental works and music First performance: Kyiv; dedicated to the first performer First performance: Kyiv; dedicated to the first performer for films such as Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors and Andrej Bielow; conductor Mykola Dyadyura. Katharina Fejer; conductor Myroslav Skoryk. The High Pass , and numerous animated cartoons. Skoryk’s works are performed in the Ukraine and The two main themes of the concerto characterise the This work was written to mark the 200th anniversary of throughout the world, such as Canada, Australia, the US, composer’s craving for sensual, delicate and fragile Fryderyk Chopin’s birth and can be seen as homage to Japan, China, and in most European countries. moods. Yet they are contrasted by episodes that violate the Polish virtuoso. It uses ‘quotations’ from his various One of his most popular pieces is Melody in A minor , their lyrical mood: marching melodies, provocative piano works – Préludes , Mazurkas and Sonatas . These which he often performs as a conductor and pianist. dances, rapid expressive fugato based on the sonorous are combined with Skoryk’s own ‘voice’ in an imitation of 1 dialogue between the violin and other instruments in the Chopin's style. -

The Ukrainian Weekly 1993, No.23

www.ukrweekly.com INSIDE: • Ukraine's search for security by Dr. Roman Solchanyk — page 2. • Chornobyl victim needs bone marrow transplant ~ page 4 • Teaching English in Ukraine program is under way - page 1 1 Publishfd by the Ukrainian National Association inc., a fraternal non-prof it association rainianWee Vol. LXI No. 23 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, JUNE 6, 1993 50 cents New York commemorates Tensions mount over Black Sea Fleet by Marta Kolomayets Sea Fleet until 1995. 60th anniversary of Famine Kyyiv Press Bureau More than half the fleet — 203 ships — has raised the ensign of St. Andrew, by Andrij Wynnyckyj inaccurate reports carried in the press," KYYIV — Ukrainian President the flag of the Russian Imperial Navy. ranging from those of New York Times Leonid Kravchuk has asked for a summit NEW YORK — On June 1, the New None of the fleet's Warships, however, reporter Walter Duranty written in the meeting with Russian leader Boris have raised the ensign. On Friday, May York area's Ukrainian Americans com 1930s, to recent Soviet denials and Yeltsin to try to resolve mounting ten memorated the 60th anniversary of the Western attempts to smear famine sions surrounding control of the Black (Continued on page 13) tragic Soviet-induced famine of І932- researchers. Sea Fleet. 1933 with a "Day of Remembrance," "Now the facts are on the table," Mr. In response, Russian Foreign Minister consisting of an afternoon symposium Oilman said. "The archives have been Andrei Kozyrev is scheduled to arrive in Parliament begins held at the Ukrainian Institute of opened in Moscow and in Kyyiv, and the Ukraine on Friday morning, June 4, to America, and an evening requiem for the Ukrainian Holocaust has been revealed arrange the meeting between the two debate on START victims held at St. -

Commemorative Coins Issued in 2019

Commemorative Coins Issued in 2019 Banknotes and Сoins of Ukraine 164 OUTSTANDING PERSONALITIES OF UKRAINE SERIES 2019 Bohdan Khanenko Put into circulation 17 January 2019 Face value, hryvnias 2 Metal Nickel silver Weight, g 12.8 Diameter, mm 31.0 Quality Special uncirculated Edge Grooved Mintage, units 35,000 Designer Engravers Maryna Kuts Volodymyr Atamanchuk, Anatolii Demianenko The commemorative coin is dedicated to Bohdan Obverse: at the top is Ukraine’s small coat of arms; Khanenko, a representative of a senior cossack dynasty, the circular legends read 2019 УКРАЇНА (2019 Ukraine) collector, patron of the arts, entrepreneur, and a public (top left), ДВІ ГРИВНІ (two hryvnias) (top right), БОГДАН figure, who was reputable in the financial and industrial ХАНЕНКО 1849–1917 (Bohdan Khanenko 1849–1917) circles and distinguished in the business and public life (at the bottom); the center of the coin shows a portrait of Kyiv. of Bohdan Khanenko in the foreground and a portrait of Varvara Khanenko in the background. On the right Collecting items was life’s work for Bohdan Khanenko. is the mint mark of the NBU’s Banknote Printing Together with his wife Varvara Khanenko, he made and Minting Works against the smooth background. a significant contribution to the cultural heritage of Ukraine: for over 40 years, Bohdan and Varvara Reverse: a symbolic composition depicting hands Khanenko collected unique pieces of art from all that hold a stylized colored picture (pad-printed). over the world, and founded the museum that currently bears their names. -

University of California UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Ukrainian Identity in Modern Chamber Music: A Performer's Perspective on Valentyn Silvestrov's Violin Sonata "Post Scriptum" and its Interpretation in the Context of Ukrainian Chamber Works. Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8874s0pn Author Khomik, Myroslava Publication Date 2014 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Ukrainian Identity in Modern Chamber Music: A Performer’s Perspective on Valentyn Silvestrov’s Violin Sonata “Post Scriptum” and its Interpretation in the Context of Ukrainian Chamber Works A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction Of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Musical Arts By Myroslava Khomik 2015 © Copyright by Myroslava Khomik 2015 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Ukrainian Identity in Modern Chamber Music: A Performer’s Perspective on Valentyn Silvestrov’s Violin Sonata “Post Scriptum” and its Interpretation in the Context of Ukrainian Chamber Works. by Myroslava Khomik Doctor of Musical Arts University of California, Los Angeles, 2015 Professor Movses Pogossian, Chair Ukrainian cultural expression has gone through many years of inertia due to decades of Soviet repression and censorship. In the post-Soviet period, since the late 80s and early 90s, a number of composers have explored new directions in creative styles thanks to new political and cultural freedoms. This study focuses on Valentyn Silvestrov’s unique Sonata for Violin and Piano “Post Scriptum” (1990), investigating its musical details and their meaning in its post- Soviet compositional context. The purpose is to contribute to a broader overview of Ukraine’s classical music tradition, especially as it relates to national identity and the ii current cultural and political state of the country. -

38 September 21, 2003

INSIDE:• National Rukh of Ukraine marks anniversary — page 3. • Third Youth Leadership Program held in D.C. — page 9. • Ukrainian named top female wrestler — page 11. Published by the Ukrainian National Association Inc., a fraternal non-profit association Vol. LXXI HE No.KRAINIAN 38 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 21, 2003 EEKLY$1/$2 in Ukraine T U With reservations,W Cabinet and Rada approve Embassy of Russia works against Ukraine’s entry into common economic space SenateWASHINGTON resolution – The Embassy ofonUkraine Famine-Genocide of the 1930s.” by Roman Woronowycz ment’s decision on what it wants to do with Russia in the United States has voiced its He continued: “Many aspects of the Kyiv Press Bureau the united economic space, but I think there opposition to a Senate resolution that rec- realization of the policies of the Soviet needs to be a careful look at how this ognizes the Great Famine of 1932-1933 in leadership of that time headed by Stalin KYIV – Ukraine’s Cabinet of Ministers agreement fits in with the country’s aspira- Ukraine as genocide. were tragic for many peoples on the terri- and Verkhovna Rada pushed through sepa- tions to join the Euro-Atlantic community,” Radio Liberty reported last week that tory of the USSR, not only for Ukrainians, rate documents on September 17 in support explained Ambassador Herbst. “I believe it sources said Russian officials have con- but also for Russians, Estonians, of the country’s entry into a common mar- is in the interest of Ukraine not to take any tacted officials at the U.S. -

Contemporary Socio-Economic Issues of Polish-Ukrainian Cross-Border Cooperation

Center of European Projects European Neighbourhood Instrument Cross-border Cooperation Programme Poland-Belarus-Ukraine 2014-2020 Publication of the Scientifi c Papers of the International Research and Practical Conference Contemporary Socio-Economic Issues of Polish-Ukrainian Cross-border Cooperation Warsaw 2017 Center of European Projects European Neighbourhood Instrument Cross-border Cooperation Programme Poland-Belarus-Ukraine 2014-2020 Publication of the Scientifi c Papers of the International Research and Practical Conference Contemporary Socio-Economic Issues of Polish-Ukrainian Cross-border Cooperation Edited by: Leszek Buller Hubert Kotarski Yuriy Pachkovskyy Warsaw 2017 Publisher: Center of European Projects Joint Technical Secretariat of the ENI Cross-border Cooperation Programme Poland-Belarus-Ukraine 2014-2020 02-672 Warszawa, Domaniewska 39 a Tel: +48 22 378 31 00 Fax: +48 22 201 97 25 e-mail: [email protected] www.pbu2020.eu The international research and practical conference Contemporary Socio-Economic Issues of Polish-Ukrainian Cross-border Cooperation was held under the patronage of Deputy Prime Minister, Minister of Economic Development and Finance Mr Mateusz Morawiecki. OF ECONOMIC The conference was held in partnership with: University of Rzeszów Ivan Franko National University of Lviv This document has been produced with the fi nancial assistance of the European Union, under Cross-border Cooperation Programme Poland-Belarus-Ukraine 2007-2013. The contents of this document are the sole respon- sibility of the Joint Technical Secretariat and can under no circumstances be regarded as refl ecting the position of the European Union. Circulation: 500 copies ISBN 978-83-64597-06-0 Dear Readers, We have the pleasure to present you this publication, which is a compendium of articles received for the Scientifi c Conference “Contemporary Socio-economic Issues of Polish-Ukrainian Cross-border Cooperation”, which took place on 15-17 November 2017 in Rzeszów and Lviv. -

NEXTET the New Music Ensemble for the 21St Century Virko Baley, Music Director and Conductor Chris Arrell, Composer-In-Residence

Department of MUSIC College of Fine Arts presents NEXTET The New Music Ensemble for the 21st Century Virko Baley, music director and conductor Chris Arrell, composer-in-residence PROGRAM Maxwell R. Lafontant Healing Waters (2013) (b. 1990) r-Jextet Ensemble Britta Epling From dewy dreams (2013) (b. 1992) Britta Epling, soprano Virko Baley , piano Enzu Chang Sketch for unaccompanied oboe (2013) (b.1981) Ben Serna-Grey, oboe Chris Arrell Mutations (2013) for violoncello and computer (b. 1970) Andrew Smith, violoncello Chris Arrell, computer Boris Lyatoshynsky Sonata-Ballade, Op. 18 (1925) (1895-1968) Valentin Silvestrov Sonata No. 3 (1979/ rev.1999) (b. 1937) Preludio Fuga Postludio Timothy Haft, piano Virko Baley From Holodomor (Red Earth. Hunger) (b. 1938) "Black wounds, on the palm of the earth" Tod Fitzpatrick, baritone Virko Baley, piano Christopher Gainey The Selfish Giant for flute and storyteller (1988) (b.1981) (with text adapted from "The Selfish Giant" by Oscar Wilde) Expulsion from the Garden Dances of Eternal Winter The Return of Spring Anastasia Patanova, flute Tod Fitzpatrick, narrator Chris Arrell Of Three Minds (2013) for soprano, piano, and computer Texts from Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird by Wallace Stevens · Michelle Latour, soprano Timothy Haft, piano Chris Arrell, computer Tuesday,December10, 2013 7:30 p.m. Dr. Arturo Rando-Grillot Recital Hall Lee and Thomas Beam Music Center University of Nevada, Las Vegas PROGRAM NOTES AND BIOGRAPHIES Chris Arrell (b. 1970, Portland, Oregon) writes music for voices, instruments, and electronics. Praised for their unconventional beauty by The Boston Music Intelligencer and hailed as "sensuous" and "highly nuanced" by the Atlanta Journal Constitution, his compositions explore counterpoints of process woven from the interplay of color, line , and harmony. -

TOCC0463DIGIBKLT.Pdf

MYROSLAV SKORYK AND HIS ORCHESTRATION OF PAGANINI’S CAPRICES by Lyubov Kyjanovska Myroslav Skoryk is one of the most prominent composers in Ukraine. He is the author of a diverse body of works, which includes opera, ballets, cantatas, instrumental concertos, orchestral works and instrumental and vocal chamber compositions; he has also written incidental and flm music. He has a chair in composition at the Lysenko Music Academy in Lviv,1 teaches composition at the National Music Academy in Kyiv, and in spring 2011 he accepted the position of Artistic Director of the National Opera in Kyiv. Skoryk was born on 13 July 1938 in Lviv. His family was deeply connected with the intellectual life of western Ukraine. His parents were educators: his mother was a chemistry teacher and his father a director of the gymnasium in Sambir, a small town in western Ukraine. Skoryk’s grandfather was a well-known ethnographer, and his grandmother’s sister was the world-famous operatic soprano Solomija Krushelnytska.2 It was indeed Skoryk’s renowned great-aunt who recognised his musical talent at an early stage and encouraged him to study music. He began his musical education in the Music School at the Lviv Conservatoire, but it did not last long. Krushelnytska was unfortunate enough to be visiting her sisters in western Ukraine in September 1939 when the Soviet army invaded. She was never able to return to her home in Italy; she was then forced by the Soviet authorities to ‘sell’ all 1 Lviv (the name is sometimes transliterated as L’viv) is the most important city in western Ukraine (and eastern Galicia). -

Culture and Customs of Ukraine Ukraine

Culture and Customs of Ukraine Ukraine. Courtesy of Bookcomp, Inc. Culture and Customs of Ukraine ADRIANA HELBIG, OKSANA BURANBAEVA, AND VANJA MLADINEO Culture and Customs of Europe GREENWOOD PRESS Westport, Connecticut • London Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Helbig, Adriana. Culture and customs of Ukraine / Adriana Helbig, Oksana Buranbaeva and Vanja Mladineo. p. cm. — (Culture and customs of Europe) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978–0–313–34363–6 (alk. paper) 1. Ukraine—Civilization. 2. Ukraine—Social life and customs. I. Buranbaeva, Oksana. II. Mladineo, Vanja. III. Title. IV. Series. DK508.4.H45 2009 947.7—dc22 2008027463 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright © 2009 by Adriana Helbig, Oksana Buranbaeva, and Vanja Mladineo All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2008027463 ISBN: 978–0–313–34363–6 First published in 2009 Greenwood Press, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. www.greenwood.com Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this book complies with the Permanent Paper Standard issued by the National Information Standards Organization (Z39.48–1984). 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 The authors dedicate this book to Marijka Stadnycka Helbig and to the memory of Omelan Helbig; to Rimma Buranbaeva, Christoph Merdes, and Ural Buranbaev; to Marko Pećarević. This page intentionally left blank Contents Series Foreword ix Preface xi Acknowledgments xiii Chronology xv 1 Context 1 2 Religion 30 3 Language 48 4 Gender 59 5 Education 71 6 Customs, Holidays, and Cuisine 90 7 Media 114 8 Literature 127 viii CONTENTS 9 Music 147 10 Theater and Cinema in the Twentieth Century 162 Glossary 173 Selected Bibliography 177 Index 187 Series Foreword The old world and the New World have maintained a fluid exchange of people, ideas, innovations, and styles. -

Concert Program

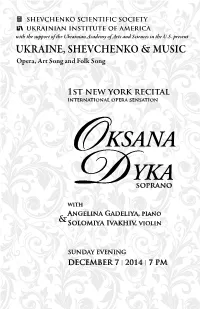

Oksana Dyka, soprano Angelina Gadeliya, piano • Solomiya Ivakhiv, violin I. Bellini Vincenzo Bellini Casta Diva (1801-1835) from Norma (1831) Program Mozart Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Porgi, amor, qualche ristoro (1756-1791) from The Marriage of Figaro (1786) Rossini Gioachino Rossini Selva opaca, Recitative and Aria (1792-1868) from Guglielmo Tell (William Tell, 1829) Ms. Dyka • Ms. Gadeliya II. Shchetynsky Alexander Shchetynsky An Episode in the Life of the Poet, (b. 1960) an afterword to the opera Interrupted Letter (2014) World Premiere Ms. Ivakhiv • Ms. Gadeliya III. From Poetry to Art Songs 1: Settings of poems by Taras Shevchenko Shtoharenko Andriy Shtoharenko Yakby meni cherevyky (1902-1992) (If I had a pair of shoes, 1939) Silvestrov Valentin Silvestrov Proshchai svite (b. 1937) (Farewell world, from Quiet Songs, 1976) Shamo Ihor Shamo Zakuvala zozulen’ka (1925-1982) (A cuckoo in a verdant grove, 1958) Skoryk Myroslav Skoryk Zatsvila v dolyni (b. 1938) (A guelder-rose burst into bloom, 1962) Mussorgsky Modest Mussorgsky Hopak (1839-1881) from the opera Sorochynsky Fair (1880) Ms. Dyka • Ms. Gadeliya 2 Program — INTERMISSION — I V. Beethoven Ludwig van Beethoven Allegro vivace (1770-1827) from Sonata in G Major, Op. 30 (1801-1802) Vieuxtemps Henri Vieuxtemps Désespoir (1820-1881) from Romances sans paroles, Op. 7, No. 2 (c.1845) Ms. Ivakhiv • Ms. Gadeliya V. From Poetry to Art Songs 2: Settings of poems by Taras Shevchenko Lysenko Mykola Lysenko Oy, odna ya odna (1842-1912) (I’m alone, so alone, 1882) Rachmaninov Sergei Rachmaninov Poliubila ya na pechal’ svoyu, (1873-1943) Op. 8, No. 4 (I have given my love, 1893) Stetsenko Kyrylo Stetsenko Plavai, plavai, lebedon’ko (1882-1922) (Swim on, swim on, dear swan, 1903) Dankevych Konstantyn Dankevych Halia’s Aria (1905-1984) from the opera Nazar Stodolia (1960) VI. -

Curriculum Vitae/Resume

CURRICULUM VITAE/RESUME HABALEVYCH VASYL PROFESSIONAL VIOLIN PLAYER Date of birth : 24-December-1990 SUMMARY Highly motivated violin player with a comprehensive background of performance. Participant of many Ukrainian and international contests and festivals. More than 10 years have been spend in a variety of ensembles, quartets, symphony orchestras and as a soloist. Skilled ensemblist in sight-reading of new pieces with a high degree of accuracy and at desired tempo from the beginning till the end. An enthusiastic team player who accepts coaching graciously and quickly incorporates feedback into performances. Poised and charismatic ensemble performer who quickly masters new repertoires, foreign musical styles. Deal with duties in a good way. Experienced collaboration with a diverse range of prominent musicians and conductors. HIGHLIGHTS • Sociable • Poised • Organized healthy way of life • Enthusiastic • Responsible • Creative • Hardworking WORK EXPERIENCE Violin player 9/2003 till Nowadays Performed a huge selection of music in a variety of styles with different orchestras. Participation in numerous competitions, festivals and concerts both locally and nationally; master classes with such prominent musicians as Bohodar Kotorovych, Kyrylo Stetsenko, Marko Komonko, Michael Strycharz, Oleh Krysa, Oleksandr Brusilovskyi. Experience in playing music in front of live audience, on television shows as a member of musical group. Accurate following of musical notation. Sight-reading of difficult music precisely and at required tempo. Play music with a foreign stylistic range as a member of duets, quartets and orchestras. Expressing music themes through tempo, phrasing, volume and dynamics. S.KRUSHELNYTSKA OPERA AND BALLET OPERA STUDIO Lviv, Ukraine Violin player 1/2012 till Nowadays Played violin in the orchestra at many stages.