TIME, BYRON's DON JUAN and the PICARESQUE TRADITION By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Document .Pdf

CNDP-CRDP n° 135 octobre 2011 Les dossiers pédagogiques « Théâtre » et « Arts du cirque » du réseau SCÉRÉN en partenariat avec le CDN de Sartrouville et des Yvelines. Une collection coordonnée par le CRDP de l’académie de Paris. L’Opéra de quat’sous Avant de voir le spectacle : la représentation en appétit ! Distanciation brechtienne et théâtre épique [page 5] Vers un renouveau du genre lyrique : l’opéra épique de Kurt Weill [page 6] de Bertolt Brecht, L’Opéra de quat’sous : musique Kurt Weill, les origines [page 7] mise en scène Laurent Frechuret, Fable et personnages direction musicale Samuel Jean [page 11] Accueil et postérité de l’œuvre Du 4 au 21 octobre 2011 au CDN de Sartrouville et des Yvelines © JEAN-MArc LobbÉ / PHOTO DE RÉPÉTITION [page 14] Rebonds et résonances [page 15] Édito Après la représentation : Plus de quatre-vingts ans après la première de L’Opéra de quat’sous, l’œuvre a-t-elle pistes de travail perdu de sa modernité, de son acuité ? « Non », répondent en chœur tous les metteurs en scène qui, de par le monde, plébiscitent cet « opéra », devenu une des œuvres les Juste avant le spectacle : plus populaires du répertoire. Et effectivement, entre l’Angleterre de 1728, l’Allemagne l’affiche [page 16] à la veille de la crise de 1929 et le contexte actuel, marqué par la crise économique, la remise en cause du pouvoir de l’argent et le questionnement sur l’homme, que D’un quat’sous à l’autre d’échos ! C’est la même « danse au bord du volcan – à quatre pas de la descente aux [page 17] enfers 1 » ! Après Laurent Pelly à la Comédie-Française, Laurent Fréchuret, directeur Les partis pris du CDN de Sartrouville et des Yvelines, s’empare de ce matériau pour son ouverture de Laurent Fréchuret, de saison. -

A Rhetorical Study of Edward Abbey's Picaresque Novel the Fool's Progress

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Theses Digitization Project John M. Pfau Library 2001 A rhetorical study of Edward Abbey's picaresque novel The fool's progress Kent Murray Rogers Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project Part of the Rhetoric Commons Recommended Citation Rogers, Kent Murray, "A rhetorical study of Edward Abbey's picaresque novel The fool's progress" (2001). Theses Digitization Project. 2079. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/2079 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the John M. Pfau Library at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses Digitization Project by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A RHETORICAL STUDY OF EDWARD ABBEY'S PICARESQUE NOVEL THE FOOL'S PROGRESS A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in English Composition by Kent Murray Rogers June 2001 A RHETORICAL STUDY OF EDWARD ABBEY'S PICARESQUE NOVEL THE FOOL,'S PROGRESS A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Kent Murray Rogers June 2001 Approved by: Elinore Partridge, Chair, English Peter Schroeder ABSTRACT The rhetoric of Edward Paul Abbey has long created controversy. Many readers have embraced his works while many others have reacted with dislike or even hostility. Some readers have expressed a mixture of reactions, often citing one book, essay or passage in a positive manner while excusing or completely .ignoring another that is deemed offensive. -

![Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8862/archons-commanders-notice-they-are-not-anlien-parasites-and-then-in-a-mirror-image-of-the-great-emanations-of-the-pleroma-hundreds-of-lesser-angels-438862.webp)

Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels

A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES WATCH THIS IMPORTANT VIDEO UFOs, Aliens, and the Question of Contact MUST-SEE THE OCCULT REASON FOR PSYCHOPATHY Organic Portals: Aliens and Psychopaths KNOWLEDGE THROUGH GNOSIS Boris Mouravieff - GNOSIS IN THE BEGINNING ...1 The Gnostic core belief was a strong dualism: that the world of matter was deadening and inferior to a remote nonphysical home, to which an interior divine spark in most humans aspired to return after death. This led them to an absorption with the Jewish creation myths in Genesis, which they obsessively reinterpreted to formulate allegorical explanations of how humans ended up trapped in the world of matter. The basic Gnostic story, which varied in details from teacher to teacher, was this: In the beginning there was an unknowable, immaterial, and invisible God, sometimes called the Father of All and sometimes by other names. “He” was neither male nor female, and was composed of an implicitly finite amount of a living nonphysical substance. Surrounding this God was a great empty region called the Pleroma (the fullness). Beyond the Pleroma lay empty space. The God acted to fill the Pleroma through a series of emanations, a squeezing off of small portions of his/its nonphysical energetic divine material. In most accounts there are thirty emanations in fifteen complementary pairs, each getting slightly less of the divine material and therefore being slightly weaker. The emanations are called Aeons (eternities) and are mostly named personifications in Greek of abstract ideas. -

Don Juan Entire First Folio

First Folio Teacher Curriculum Guide Don Juan by Molière translated, adapted and directed by Stephen Wadsworth January 24—March 19, 2006 First Folio Teacher Curriculum Guide Table of Contents Page Number Welcome to the Shakespeare Theatre Company’s production ofDon Juan by Molière! A Brief History of the Audience…………………….1 Each season, the Shakespeare Theatre Company About the Playwright presents five plays by William Shakespeare and other classic playwrights. The Education Department Molière’s Life………………….…………………………………3 continues to work to deepen understanding, Molière’s Theatre…….……………………………………….4 appreciation and connection to classic theatre in 17th•Century France……………………………………….6 learners of all ages. One approach is the publication of First Folio: Teacher Curriculum Guides. About the Play Synopsis of Don Juan…………………...………………..8 In the 2005•06 season, the Education Department Don Juan Timeline….……………………..…………..…..9 will publish First Folio: Teacher Curriculum Guides for Marriage & Family in 17th•Century our productions ofOthello, The Comedy of Errors, France…………………………………………………...10 Don Juan, The Persiansand Love’s Labor’s Lost. The Guides provide information and activities to help Splendid Defiance……………………….....................11 students form a personal connection to the play before attending the production at the Shakespeare Classroom Connections Theatre Company. First Folio guides are full of • Before the Performance……………………………13 material about the playwrights, their world and the Translation & Adaptation plays they penned. Also included are approaches to Censorship explore the plays and productions in the classroom Questioning Social Mores before and after the performance.First Folio is Playing Around on Your Girlfriend/ designed as a resource both for teachers and Boyfriend students. Commedia in Molière’s Plays The Shakespeare Theatre Company’s Education Department provides an array of School, • After the Performance………………………………14 Community, Training and Audience Enrichment Friends Don’t Let Friends.. -

From Tristan to Don Juan: Romance and Courtly Love in the Fiction Of

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OpenGrey Repository From Tristan to Don Juan: Romance and courtly love in the fiction of three Spanish American authors. By Rosix E. Rincones Díaz A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham For the degree of DOCTOR IN PHILOSOPHY Department of Hispanic Studies School of Languages, Cultures, Art History and Music College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham September 2011 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Content listings Abstract Acknowlegements Chapter One: Introduction 1 Chapter Two: García Márquez’s Florentino: A Reinvented Don Juan. 52 Chapter Three: Álvaro Mutis’s La Última Escala del Tramp Steamer as a development of the courtly romance: The poetry of inner exploration. 125 Chapter four: The two spaces of Pedro Páramo: From the decadent patriarchal order of Comala to the Ideology of Courtly love. 198 Conclusion 248 Bibliography 252 Abstract This thesis is centred on Gabriel García Márquez’s novel El amor en los tiempos del cólera, Álvaro Mutis’ novella La última escala del Tramp Steamer, and Juan Rulfo’s novel Pedro Páramo. -

De Opkomst Van De Nederlandsche Republiek. Deel 4 (Vert

De opkomst van de Nederlandsche Republiek. Deel 4 J.L. Motley vertaling R.C. Bakhuizen van den Brink bron J.L. Motley, De opkomst van de Nederlandsche Republiek. Deel 4 (vert. R.C. Bakhuizen van den Brink). Van Stockum, Den Haag 1879 Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/motl001opko04_01/colofon.htm © 2008 dbnl 5 Tweede hoofdstuk De keerzijde Plechtige intrede van Don Juan in Brussel. - Keerzijde van de schilderij. - Geheime briefwisseling van Don Juan en Escovedo met Antonio Perez. - Aanslagen om den landvoogd in hechtenis te nemen. - Zijn moedeloosheid en sombere voorgevoelens. - Overhelling tot strenge maatregelen. - Standpunt en beginselen van Oranje. - Zijne denkwijs over het vraagstuk van den vrede en oorlog. - Zijne verdraagzaamheid jegens Katholieken en Doopsgezinden. - Dood van Viglius. - Nieuwe zending van den landvoogd aan Oranje. - Bijzonderheden der bijeenkomsten te Geertruidenberg. - Aard en gevolgen van die onderhandelingen. - Uitwisseling van stukken tusschen de gezanten en Oranje. - Pieter Panis om ketterij ter dood gebracht. - Drie partijen in de Nederlanden. - Veinzerij van Don Juan. - Hij vreest gevangen genomen te worden. Het spaansche krijgsvolk had op het eind van April 1577 het land verlaten, en Don Juan deed nu op den eersten Mei zijne plechtige intrede in Brussel. Sedert lang had geen zoo feestelijke Meidag de harten der Brabanders tot vroolijkheid gestemd. Zooveel hoogtijdspracht had men sinds jaren niet in de Nederlanden gezien. In statigen optocht bracht de burgerij, door zesduizend soldaten voorafgegaan, en door de vrije gilden der boogschutters en kolveniers in hunne schilderachtige kostumen begeleid, den jongen Vorst door de straten der hoofdstad. Don Juan reed te paard, in een groenen mantel gehuld, tusschen den bisschop van Luik en den pauselijken Nuncius(1), onder (1) BOR, X. -

Does the Picaresque Novel Exist?*

Published in Kentucky Romance Quarterly, 26 (1979): 203-19. Author’s Web site: http://bigfoot.com/~daniel.eisenberg Author’s email: [email protected] Does the Picaresque Novel Exist?* Daniel Eisenberg The concept of the picaresque novel and the definition of this “genre” is a problem concerning which there exists a considerable bibliography;1 it is also the * [p. 211] A paper read at the Twenty-Ninth Annual Kentucky Foreign Language Conference, April 24, 1976. I would like to express my appreciation to Donald McGrady for his comments on an earlier version of this paper. 1 Criticism prior to 1966 is competently reviewed by Joseph Ricapito in his dissertation, “Toward a Definition of the Picaresque. A Study of the Evolution of the Genre together with a Critical and Annotated Bibliography of La vida de Lazarillo de Tormes, Vida de Guzmán de Alfarache, and Vida del Buscón,” Diss. UCLA, 1966 (abstract in DA, 27 [1967], 2542A– 43A; this dissertation will be published in a revised and updated version by Castalia. Meanwhile, the most important of the very substantial bibliography since that date, which has reopened the question of the definition of the picaresque, is W. M. Frohock, “The Idea of the Picaresque,” YCGL, 16 (1967), 43–52, and also his “The Failing Center: Recent Fiction and the Picaresque Tradition,” Novel, 3 (1969), 62–69, and “Picaresque and Modern Literature: A Conversation with W. M. Frohock,” Genre, 3 (1970), 187–97, Stuart Miller, The Picaresque Novel (Cleveland: Case Western Reserve, 1967; originally entitled, as Miller’s dissertation at Yale, “A Genre Definition of the Picaresque”), on which see Harry Sieber’s comments in “Some Recent Books on the Picaresque,” MLN, 84 (1969), 318–30, and the review by Hugh A. -

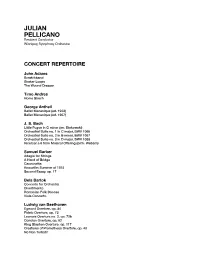

Julian Pellicano Repertoire Copy

JULIAN PELLICANO Resident Conductor Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra CONCERT REPERTOIRE John Adams Scratchband Shaker Loops The Wound Dresser Timo Andres Home Strech George Antheil Ballet Mecanique (ed. 1923) Ballet Mecanique (ed. 1957) J. S. Bach Little Fugue in G minor (arr. Stokowski) Orchestral Suite no. 1 in C major, BWV 1066 Orchestral Suite no. 2 in B minor, BWV 1067 Orchestral Suite no. 3 in D major, BWV 1068 Ricercar a 6 from Musical Offering (orch. Webern) Samuel Barber Adagio for Strings A Hand of Bridge Canzonetta Knoxville: Summer of 1915 Second Essay, op. 17 Bela Bartok Concerto for Orchestra Divertimento Romanian Folk Dances Viola Concerto Ludwig van Beethoven Egmont Overture, op. 84 Fidelo Overture, op. 72 Leonore Overture no. 3, op. 72b Coriolan Overture, op. 62 KIng Stephen Overture, op. 117 Creatures of Prometheus Overture, op. 43 No Non Turbati! Octet, op. 103 Piano Concerti no. 1 - 5 Symphonies no. 1 - 9 Violin Concerto, op. 61 Alban Berg Drei Orchesterstucke, op. 6 Hector Berlioz Roman Carnival Overture Royal Hunt and Storm from Les Troyens Symphonie Fantastique, op. 14 Scene D’Amour from Romeo and Juliet Leonard Bernstein Overture to Candide On the Town: Three Dance Episodes Overture to WEst Side Story (ed. Peress) Symphonic Dances from West Side Story Slava! Georges Bizet Carmen Suite no. 1 Carmen Suite no. 2 L’Arlesienne Suite no. 1 L’Arlesienne Suite no. 2 Alexander Borodin In the Steppes of Central Asia Polovtsian Dances Symphony no. 2 Johannes Brahms Academic Festival Overture, op. 80 Hungarian Dances no. 1,3,5,6,20,21 Symphonies no. -

Richard Schechner

“We Still Have to Dance and Sing” An Interview with Richard Foreman Richard Schechner Richard Foreman is an incessant author and highly focused director. Since 1992, at St. Mark’s Church on 2nd Avenue in Manhattan, Foreman has directed 11 of his own plays. The most recent, Maria del Bosco, opened on 27 December 2001. Over the years, with his Ontological-Hysteric Theatre, founded in 1968, Foreman has directed more than 50 of his own plays—and there are more plays still unproduced. Foreman also has frequently directed the works of others. Among my favorite Foreman productions are Brecht’s Threepenny Opera at Lin- coln Center in 1976, Moliere’s Don Juan at the Guthrie Theatre in 1982, and Suzan-Lori Parks’s Venus at the Public Theatre in New York in 1996. Foreman has often been in the pages of TDR, starting with his “Ontologic-Hysteric Man- ifesto II” in 1974 (18:3, T63) up to the program notes for Pearls for Pigs in 1998 (42:2, T158). Foreman’s plays have been collected in a number of books, from Plays and Manifestos (New York University Press, 1976) to the most recent, Par- adise Hotel and Other Plays (Overlook Press, 2001). SCHECHNER: I want to focus on post–September 11th. Your play, Now That Communism Is Dead My Life Feels Empty [2001], was to some degree about en- tering a new historic era. But now [November 2001] it appears that the U.S. government, either by intention or accident, has found a way to continue the Cold War under different auspices. -

Picaresque Translation and the History of the Novel.Pdf

The Picaresque, Translation and the History of the Novel. José María Pérez Fernández University of Granada 1. Introduction The picaresque as a generic category originates in the Spanish Siglo de Oro, with the two novels that constitute the core of its canon—the anonymous Lazarillo de Tormes (1554) and Mateo Alemán’s Guzmán de Alfarache (1599, 1604). In spite of the fact that definitions of the picaresque are always established upon these Spanish foundations, it has come to be regarded as a transnational phenomenon which also spans different periods and raises important questions about the nature and definition of a literary genre. After its appearance in the Spanish 16th century, picaresque fiction soon spread all over Europe, exerting a particularly important influence during the 17th and 18th centuries in Germany, France and above all England, after which its impact diminished gradually. A study of the picaresque calls for a dynamic, flexible, and open-ended model. When talking about the picaresque we should not countenance it as a solid and coherent whole, but rather as a fluid set of features that had a series of precedents, an important foundational moment in the Spanish 16th and 17th centuries, and then spread out in a non-linear way. It grew instead into a complex web whose heterogeneous components were brought together by the fact that these new varieties of prose fiction were responding to similar cultural, social and economic realities. These new printed artefacts resulted from the demands of readers as consumers and the policies of publishers and printers as producers of marketable goods. -

Don Juan Study Guide

Don Juan Study Guide © 2017 eNotes.com, Inc. or its Licensors. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this work covered by the copyright hereon may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, Web distribution or information storage retrieval systems without the written permission of the publisher. Summary Don Juan is a unique approach to the already popular legend of the philandering womanizer immortalized in literary and operatic works. Byron’s Don Juan, the name comically anglicized to rhyme with “new one” and “true one,” is a passive character, in many ways a victim of predatory women, and more of a picaresque hero in his unwitting roguishness. Not only is he not the seductive, ruthless Don Juan of legend, he is also not a Byronic hero. That role falls more to the narrator of the comic epic, the two characters being more clearly distinguished than in Byron’s Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage. In Beppo: A Venetian Story, Byron discovered the appropriateness of ottava rima to his own particular style and literary needs. This Italian stanzaic form had been exploited in the burlesque tales of Luigi Pulci, Francesco Berni, and Giovanni Battista Casti, but it was John Hookham Frere’s (1817-1818) that revealed to Byron the seriocomic potential for this flexible form in the satirical piece he was planning. The colloquial, conversational style of ottava rima worked well with both the narrative line of Byron’s mock epic and the serious digressions in which Byron rails against tyranny, hypocrisy, cant, sexual repression, and literary mercenaries. -

CONTENTS Page the SEXUAL BOUNDARY

( i) CONTENTS Page EDITORIAL NOTE .•• III •••••••• III •••••• III III •• III • III ••••• _ III III ...... III ..... III • ii THE SEXUAL BOUNDARY - PURITY: HETEROSEXUALITY AND VIRGINITY •..• III • III ••• III •••••••• III ••• III III •• III •••• III III •• III III III III ••• III III III III • III .137 Kirsten Hastrup, Institute of Social Anthropology, Oxford. THE CONSCIOUSNESS OF CONSCIOUSNESS •••••••••••••••••••••••••148 Mike Taylor, Institute of Social Anthropology, Oxford. THE METAPHOR~1ETONYM DISTINCTION: A CO~~NT ON CAMPBELL •••••••••••• III III • III ••••••••••• III III III III III ••••• III III • 6 •• III ••••••• 151 Jan Oveson, Institute of Social Anthropology, O~ford. "THE MIND-FORG'D MANACLES" :CASTANEDA IN THE ltJORLD OF DON JUAN III •••••••• III •••••••••••• III •• III •••••• III •• • ,0 ••• •• 155 Martin Cantor, Instit~te of Social Anthropology, Oxford. CHILDREN IN THE PLAYGROUND •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••173 Charlotte Hardman, School of Oriental and African Studies. REVIEW ARTICLE: RACE •••••••••• III ••••••• III ••••••••••• III •• " ••• III .189 M.G. WhiS"SO'ii, University of Cape Town. BOOK REVIEWS: Maclean: Magical Medicine: A Nigerian Case- Study - by Helen Callaway••.•••••••••••••••••••••••195 Glucksmann: Structuralist Analysis in Contemporary Social T~ought: A Comparison of the theories-2! Claude Levi-Strauss and Louis Althusser - by Paul Dresch. III •••• III •••••• Ill, •••• " " • III ••••••••• Ill •••• 0 • •• 198 . Roper: The Women of Nar -by Juliet Blair••••••• ~ •• 199 Chaudhuri: Scholar Extraordinary: The