Is the March 23Rd Movement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KAS International Reports 06/2013

56 KAS INTERNATIONAL REPORTS 6|2013 M23 REBELLION A FURTHER CHAPTER IN THE VIOLENCE IN EASTERN CONGO Steffen Krüger Steffen Krüger is Resident Representa- In recent years, the provinces of North Kivu and South tive of the Konrad- Kivu in the east of the Democratic Republic of the Congo Adenauer- Stiftung have once again become the epicentre of various conflicts in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. in the African Great Lakes Region. The two provinces and their population of ten million were affected particularly strongly by the three Congo Wars between 1996 and 2006. For years they have been the scene of looting, indiscrimi- nate killing and other crimes committed by various parties to the conflict. The region is very densely populated and rich in mineral resources. The reserves of gold, diamonds, tin, coltan1 and other raw materials are worth hundreds of billions of euros. In April 2012, the M23 Rebellion2 began with the mutiny of 600 Congolese soldiers, bringing a new wave of violence and destruction to the region. Many women, children and men fell victim to the conflict and over 900,000 people had to flee their homes yet again. Nobody knows the precise figures because many are left to their own devices and have hardly any access to assistance. The fighting has now stopped, but the insecurity of not knowing whether a new conflict may break out remains. Various national and inter- national actors have analysed the events during the past few months and discussed solutions for a lasting peace. 1 | Coltan is an ore, which is mainly processed to extract the metal tantalum. -

Mapping Conflict Motives: M23

Mapping Conflict Motives: M23 1 Front Cover image: M23 combatants marching into Goma wearing RDF uniforms Antwerp, November 2012 2 Table of Contents Introduction 4 1. Background 5 2. The rebels with grievances hypothesis: unconvincing 9 3. The ethnic agenda: division within ranks 11 4. Control over minerals: Not a priority 14 5. Power motives: geopolitics and Rwandan involvement 16 Conclusion 18 3 Introduction Since 2004, IPIS has published various reports on the conflict in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). Between 2007 and 2010 IPIS focussed predominantly on the motives of the most significant remaining armed groups in the DRC in the aftermath of the Congo wars of 1996 and 1998.1 Since 2010 many of these groups have demobilised and several have integrated into the Congolese army (FARDC) and the security situation in the DRC has been slowly stabilising. However, following the November 2011 elections, a chain of events led to the creation of a ‘new’ armed group that called itself “M23”. At first, after being cornered by the FARDC near the Rwandan border, it seemed that the movement would be short-lived. However, over the following two months M23 made a remarkable recovery, took Rutshuru and Goma, and started to show national ambitions. In light of these developments and the renewed risk of large-scale armed conflict in the DRC, the European Network for Central Africa (EURAC) assessed that an accurate understanding of M23’s motives among stakeholders will be crucial for dealing with the current escalation. IPIS volunteered to provide such analysis as a brief update to its ‘mapping conflict motives’ report series. -

Democratic Republic of Congo

JANUARY 2013 COUNTRY SUMMARY DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO State security forces and Congolese and foreign armed groups committed numerous and widespread violations of the laws of war against civilians in eastern and northern Democratic Republic of Congo (Congo). In late 2011, opposition party members and supporters, human rights activists, and journalists were threatened, arbitrarily arrested, and killed during presidential and legislative election periods. Gen. Bosco Ntaganda, sought on arrest warrants from the International Criminal Court (ICC) for war crimes and crimes against humanity, defected from the army in March and started a new rebellion with other former members of the National Congress for the Defense of the People (CNDP), a rebel group integrated into the army in early 2009. The new M23 rebel group received significant support from Rwandan military officials. Its fighters were responsible for widespread war crimes, including summary executions, rapes, and child recruitment. As the government and military focused attention on defeating the M23, other armed groups became more active in other parts of North and South Kivu, attacking civilians. Abuses during National Elections Presidential and legislative elections in November 2011 were characterized by targeted attacks by state security forces on opposition party members and supporters, the use of force to quell political demonstrations, and threats or attacks on journalists and human rights activists. President Joseph Kabila was declared winner of the November 28, 2011 election, which international and national election observers criticized as lacking credibility and transparency. 1 The worst election-related violence was in the capital, Kinshasa, where at least 57 opposition party supporters or suspected supporters were killed by security forces—mostly Kabila’s Republican Guard—between November 26 and December 31. -

The Evolution of an Armed Movement in Eastern Congo Rift Valley Institute | Usalama Project

RIFT VALLEY INSTITUTE | USALAMA PROJECT UNDERSTANDING CONGOLESE ARMED GROUPS FROM CNDP TO M23 THE EVOLUTION OF AN ARMED MOVEMENT IN EASTERN CONGO rift valley institute | usalama project From CNDP to M23 The evolution of an armed movement in eastern Congo jason stearns Published in 2012 by the Rift Valley Institute 1 St Luke’s Mews, London W11 1Df, United Kingdom. PO Box 30710 GPO, 0100 Nairobi, Kenya. tHe usalama project The Rift Valley Institute’s Usalama Project documents armed groups in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The project is supported by Humanity United and Open Square and undertaken in collaboration with the Catholic University of Bukavu. tHe rift VALLEY institute (RVI) The Rift Valley Institute (www.riftvalley.net) works in Eastern and Central Africa to bring local knowledge to bear on social, political and economic development. tHe AUTHor Jason Stearns, author of Dancing in the Glory of Monsters: The Collapse of the Congo and the Great War of Africa, was formerly the Coordinator of the UN Group of Experts on the DRC. He is Director of the RVI Usalama Project. RVI executive Director: John Ryle RVI programme Director: Christopher Kidner RVI usalama project Director: Jason Stearns RVI usalama Deputy project Director: Willy Mikenye RVI great lakes project officer: Michel Thill RVI report eDitor: Fergus Nicoll report Design: Lindsay Nash maps: Jillian Luff printing: Intype Libra Ltd., 3 /4 Elm Grove Industrial Estate, London sW19 4He isBn 978-1-907431-05-0 cover: M23 soldiers on patrol near Mabenga, North Kivu (2012). Photograph by Phil Moore. rigHts: Copyright © The Rift Valley Institute 2012 Cover image © Phil Moore 2012 Text and maps published under Creative Commons license Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by/nc-nd/3.0. -

Policy Brief 99.Indd

AFRICA INSTITUTE OF SOUTH AFRICA BriefinG NO 99 NOVEMBER 2013 We Need to Do Better, and We Can: One Group Surrendering is Hardly a Return to Peace and Prosperity Sylvester Bongani Maphosa1 There is no bigger challenge facing humanity than how to build lasting peace in the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Despite the military defeat of the rebel M23 by forces led by the Congolese army and the United Nations Intervention Brigade, the net peace and security dividends appear indiscernible at local community level. How do communities in conflict, and/ or emerging from violent conflict, develop infrastructures for peace to avoid reverting to armed conflict? From a conflict-resolution viewpoint, this brief describes a six-part taxonomy of peace and suggests a three-pronged systemic approach policy makers should adopt to prevent future large-scale violence. Furthermore, the strategy should assume a multi-track approach incorporating whole-of-society vertical, middle-out and horizontal relationships. Introduction integrated into the national army after a peace deal with the government on 23 March 2009. The Although most of the DRC has enjoyed relative deserters accused the government of failing to live peace in the recent decade, the eastern expanse, up to the terms of the pact (the rebel group M23 including the North Kivu, South Kivu and Orientale takes its name from the 23 March 2009 CNDP-DRC provinces, remains a theatre of widespread government peace agreement). According to the civilian atrocities and human rights abuse. The United Nations (UN) Group of Experts and several current tragedy in Goma and surrounding North intelligence reports, M23 enjoys direct support Kivu has been going on for over 20 months now. -

William Kandowe 546338 Supervisor Dr Norman Sempijja Co Supervisor Ekeminiabasi Eyita-Okon Examining the Impact of Peacekeeping

FACULTY OF HUMANITIES DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS William Kandowe 546338 Supervisor Dr Norman Sempijja Co Supervisor Ekeminiabasi Eyita-Okon Examining the impact of peacekeeping and peace enforcement in Democratic Republic Congo–the cases of Operation Artemis 2003 and Force Intervention Brigade 2013. Research submitted to the Faculty of Humanities in fulfilment of the requirements of the Master‘s Degree in International Relations, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg South Africa Declaration I William Kandowe declare that this is solely my own work, and where otherwise appropriate referencing has been made. Signed---------------------------------------------Date--------------------------------------------------------- i Dedication To my wife Marjory and my children: Laura Leaza, Lavender Layla and Lee William. ii Acknowledgements I wish to thank my supervisor Dr Norman Sempijja, co-supervisor Ekeminiabasi Okon, my wife Marjory Muneri, as well as my daughters Laura, Lavender and my son Lee William. I would further like to thank Lyn Brown, Dickson Kamungeremu, Princington, Rudo, Fellowship and Isaac. Further thanks are due to Professor Gilbert Kadiyagala, and Dr Sandi Sithole. , Professor Sheila Meintjes–your assistance with violent and conflict discussion is gratefully acknowledged, and to Dr Roxanne Richter your encouragement strengthened me. I am also very happy with the following people who worked closely with me during my research: Misheck Mudzengerere; Farai Sankurani; Mum Muneri; Siwach Mandivengerei; Enos Tsikiwa; Mr and Mrs Jervas Mudzengerere; as well as Jervas Nyokanhete. My friends from Wits University and staff from the International Relations Department, and to all the Masters Students I shared ideas with–thank you. Those whom I worked with I appreciate the work you did during my absence without supervision. -

Can Force Be Useful in the Absence of a Political Strategy? Lessons from the UN Missions to the DR Congo

Can Force be Useful in the Absence of a Political Strategy? Lessons from the UN missions to the DR Congo Congo Research Group December 2015 Jason K. Stearns CONGO RESEARCH GROUP | GROUP D’ETUDE SUR LE CONGO Congo Research Group (CRG) is an independent, non-profit research project dedicated to understanding the violence that affects millions of Congolese. We carry out rigorous research on different aspects of the conflict––our first report, for example, investigates who is behind a series of massacres in the Beni region, while others reports look at links between elections and conflict, and at armed groups in the Kivus region. All of our research is informed by deep historical and social knowledge of the problem at hand, and we often invest months of field research, speaking with hundreds of people to produce a report. We are based at the Center on International Cooperation at New York University. We publish in English and French. Can Force Be Useful in the Absence of a Political Strategy? Lessons from the UN missions to the DR Congo TABLE OF CONTENTS A Brief History of the Recent UN Missions in the DR Congo 4 Analysis 7 The Military Failures and Successes 8 The Enabling Political Environment 9 Conclusion 10 About the Author 11 Endnotes 11 CAN FORCE BE USEFUL IN THE ABSENCE OF A POLITICAL STRATEGY? LESSONS FROM THE UN MISSIONS TO THE DR CONGO This analysis was initially written for the Center on International Cooperation and the International Peace Institute as part of a series of internal papers for the High Level Independent Panel on Peace Operations. -

Perpetuation of Instability in the Democratic Republic of the Congo: When the Kivus Sneeze, Kinshasa Catches a Cold

Perpetuation of instability in the Democratic Republic of the Congo: When the Kivus sneeze, Kinshasa catches a cold By Joyce Muraya and John Ahere 22 YEARS OF CONTRIBUTING TO PEACE ISSUE 1, 2014 Perpetuation of instability in the Democratic Republic of the Congo: When the Kivus sneeze, Kinshasa catches a cold By Joyce Muraya and John Ahere Occasional Paper Series: Issue 1, 2014 About ACCORD The African Centre for the Constructive Resolution of Disputes (ACCORD) is a non-governmental organisation working throughout Africa to bring creative solutions to the challenges posed by conflict on the continent. ACCORD’s primary aim is to influence political developments by bringing conflict resolution, dialogue and institutional development to the forefront as alternatives to armed violence and protracted conflict. Acknowledgements The authors extend their appreciation to all colleagues who supported the development and finalisation of this paper, including Daniel Forti, Charles Nyuykonge and Sabrina Ensenbach for their invaluable contributions to the paper’s structure and content and to Petronella Mugoni for her assistance in formatting the paper. The authors also appreciate the cooperation of colleagues in ACCORD’s Peacebuilding and Peacemaking units, for affording them the time and space to conduct the research necessary for writing this publication. About the authors Joyce Muraya holds a Master of Arts degree in International Relations from the United States International University in Nairobi, Kenya. Muraya served in Kenya’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs for a year and a half and participated in a nine-month internship programme in the Peacebuilding Unit at ACCORD. She has published on gender and women’s issues, with a focus on women’s reproductive rights. -

Reintegrating Warlords Into Congo's Army?

Reintegrating Warlords into Congo’s Army? After months of deliberations in Kampala, Uganda, the government of the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the M23 rebel group are moving closer toward a deal that would provide amnesty and reintegration for all rebels, no matter the abuses they com- mitted. Under the command of Sultani Makenga, the M23 is implicated by the United Nations in committing serious human-rights violations, including killing, maiming, sexual violence, abduction, and forced displacement.1 While Kinshasa has offered M23 commanders amnesty and reintegration into the national army only on a case-by-case basis, the rebel group—which still has forces on the ground that have threatened to recapture the North Kivu capital city of Goma—is pushing for full amnesty and reintegration for all its members. Reintegrating senior-level rebel leaders into Congo’s army that have orchestrated the mass recruitment of child soldiers and massacres would do little to break the cycle of impunity that feeds Congo’s astronomical levels of violence. Rank-and-file troops should be reintegrated, but unless the worst perpetrators of human-rights violations are brought to justice, there will be no lasting peace in eastern Congo. Furthermore, if there are no major initiatives to demobilize large numbers of rank-and-file combatants and to reform the Congolese army, the professionalism of that army will continue to deterio- rate, continuing to result in serious repercussions for the civilian population. Equally worrisome is that any haphazard deal with the M23 will undermine the “Peace, Security and Cooperation Framework for the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the Region” signed on February 24, 2013, by U.N. -

Rwanda: in Brief

Rwanda: In Brief Updated May 14, 2019 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R44402 Rwanda: In Brief Summary Rwanda, a small landlocked country in central Africa’s Great Lakes region, has seen rapid development and security gains since about 800,000 people—mostly members of the ethnic Tutsi minority—were killed in the 1994 genocide. The ruling Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) ended the genocide by seizing power in mid-1994 and has been the dominant force in Rwandan politics ever since. The Rwandan government has won donor plaudits for its efforts to improve health, boost agricultural output, encourage foreign investment, and promote women’s empowerment. Yet, analysts debate whether Rwanda’s authoritarian political system—and periodic support for rebel groups in neighboring countries—could jeopardize the country’s stability in the long-run, or undermine the case for donor support. President Paul Kagame, in office since 2000, won reelection to another seven-year term in 2017 with nearly 99% of the vote, after the adoption of a new constitution that effectively exempted him from term limits through 2034. Kagame’s overwhelming margin of victory may reflect popular support for his efforts to stabilize and transform Rwandan society, as well as a political system that involves constraints on opposition activity and close government scrutiny of citizen behavior. In response to external criticism, Kagame has generally denied specific allegations of abusing human rights while asserting that restrictions on civil and political rights are necessary to prevent the return of ethnic violence. The United States and Rwanda have cultivated close ties since the mid-1990s, underpinned by U.S. -

Strategic Pressure a Blueprint for Addressing New Threats and Supporting Democratic Change in the DRC

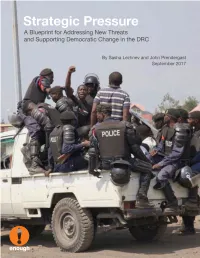

Cover: Pro-democracy Lucha activist Luc Nkulula and others are placed under arrest after a peaceful protest in Goma, December 2016. Photo: Fred Bauma. Strategic Pressure A Blueprint for Addressing New Threats and Supporting Democratic Change in the DRC By Sasha Lezhnev and John Prendergast September 25, 2017 Nearly nine months after signing a political deal aimed at ushering in a landmark democratic transition in the Democratic Republic of Congo, President Joseph Kabila’s subversion of the accord places Congo at risk of much greater violence. It is also now creating the potential for regional instability and the possible disruption in the supply of minerals strategically important to U.S. national security and to U.S. and other global manufacturers. Kabila’s attempt to stay in power at all costs is moving Congo from a fragile democracy to a dictatorship. It has already sparked significant repression, caused armed conflict in the Kasai region where 1.4 million people have been displaced, and all major U.S. companies with direct investments have fled Congo. Unrest that is rising in several areas of the country could also spread to mineral-rich Katanga, where 50 to 60 percent of the world’s cobalt reserves lie, 1 creating a threat to U.S. defense, auto, and electronics industries. A much more robust strategy is needed to prevent a far costlier disaster with U.S. national security and regional instability implications, and to help Congo move toward a democratic transition. Over the past year, the international community as well as Congo’s opposition and civil society have deployed some elements of a necessary strategy of pressure and negotiation to support a transition. -

In the Democratic Republic of the Congo by Adam Day

Case Study 1 in the Democratic Republic of the Congo by Adam Day 22 This case study was developed to inform The Political Practice of Peacekeeping by Adam Day, Aditi Gorur, Victoria K. Holt and Charles T. Hunt - a policy paper exploring how the UN develops and implements political strategies to address some of the most complex and dangerous conflicts in the world. The other case studies examine the political strategies of the UN peacekeeping missions in the the Central African Republic, Darfur, South Sudan and Mali. Adam Day is Director of Programmes at United Nations University Centre for Policy Research. In 2016, the author served as the Senior Political Advisor to MONUSCO, based in Kinshasa. The author is grateful to Alan Doss and Ugo Solinas for having reviewed this study. The views expressed in this report are not those of MONUSCO, any errors are the author’s. nitially deployed in the midst of the in which the Security Council’s mandates Second Congolese War in 1999, the during these watershed moments were I UN peacekeeping mission in the translated into political strategies and/ Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) or approaches by the UN Secretariat and is one of the longest serving missions mission leadership. This report contributes in the UN today. Over the course of its to a joint United Nations University/ deployment, the mission has undergone Stimson Center research project on the dramatic changes, beginning as a small political role of UN peacekeeping, in ceasefire observer mission and eventually support of the Action for Peacekeeping swelling into a large multi-dimensional initiative by the UN’s Department of Peace presence with an ambitious electoral Operations (DPO).