9 Work, Workers, and Labour Conflicts in the Shipyard Bazán /Navantia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Navantia Corporate Executive Board

Navantia Corporate Executive Board Executive Chairwoman Board of Directors Internal Audit Mª Ángeles Trigo Quiroga Susana de Sarriá Sopeña General Counsel and Strategy Secretary of the Board Javier Romero Yacobi Miguel Orozco Giménez Technology Center Human Resources M. Ángel Recamán Rivas Fernando Ramírez Ruiz Commercial & Business Corporate Development Juan Ramón Lueje Álvarez Sofía Honrubia Checa Administration & Engineering and Product Finance & Processes Development Operations and Luis J. Romero Sánchez Francisco Vílchez Business Units Rodríguez Gonzalo Mateo‐Guerrero Alcázar Bay of Cádiz Cartagena Ferrol Estuary Systems Shiprepairs Navantia Australia Shipyard Shipyard Shipyard Agustín Álvarez Alfredo Gordo Donato Martínez Pablo López Díez Rafael Suárez Pérez Álvaro Vela Parodi Blanco Álvarez Pérez de Rojas CONFIDENCIAL[*(Confidencial Comercial)*][*(Confidencial Comercial)*] COMERCIAL CONFIDENCIAL 25 de julio de 2018 0 BUSINESS DIVISIONS. MAIN FUNCTIONS Operations and Business Units. Responsible for managing the company's six main business units: Cartagena Shipyard, Ferrol Estuary Shipyard and Bay of Cadiz Shipyard, Systems and Repairs Business Units and Navantia Australia. It will mainly integrate the functions of the previous Directions of Programs, Industrial and Systems and the Engineering and Procurement activities related to these operations and businesses. For the development of its responsibilities, it will have two specific support functions: "Planning and Monitoring" and "Coordination of Operations Procurement“ Engineering and Product & Processes Development. It will be responsible for the functions of Conceptual Engineering, Strategic Relationships with suppliers, Corporate Procurements, and Corporate Quality, enhancing their integration and synergies for the development and improvement of competitive products and services. It will lead the PUMA project, the standardization plans and the homogenization of engineering processes in collaboration with the Technical Design Authorities Business Development & Commercial. -

Australia's Naval Shipbuilding Enterprise

AUSTRALIA’S NAVAL SHIPBUILDING ENTERPRISE Preparing for the 21st Century JOHN BIRKLER JOHN F. SCHANK MARK V. ARENA EDWARD G. KEATING JOEL B. PREDD JAMES BLACK IRINA DANESCU DAN JENKINS JAMES G. KALLIMANI GORDON T. LEE ROGER LOUGH ROBERT MURPHY DAVID NICHOLLS GIACOMO PERSI PAOLI DEBORAH PEETZ BRIAN PERKINSON JERRY M. SOLLINGER SHANE TIERNEY OBAID YOUNOSSI C O R P O R A T I O N For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR1093 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-0-8330-9029-4 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2015 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions.html. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface The Australian government will produce a new Defence White Paper in 2015 that will outline Australia’s strategic defense objectives and how those objectives will be achieved. -

Foreign Shipyard Visits Public Report

Foreign Shipyard Visits Final Report Singapore and South Korea – April, 2011 Italy and Spain – May, 2011 Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited July 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. FOREWORD .......................................................................................................................................... 3 2. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ........................................................................................................................ 4 3. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................................................................... 6 4. APPROACH AND FOCUS AREAS ......................................................................................................... 11 5. KEY OBSERVATIONS ........................................................................................................................... 13 6. PROPOSED ACTIONS / RECOMMENDATIONS.................................................................................... 16 7. APPENDICES ........................................................................................................................................... 7.1 Report of Team Observations – Asian Shipyard Visit................................................................. 17 7.2 Report of Team Observations – European Shipyard Visit .......................................................... 29 7.3 Overview of the Asian and European Shipyards Visited ............................................................ 38 7.4 -

This Relates to Agenda Item No. 2 Transportation Committee June 7, 2019

This Relates to Agenda Item No. 2 Transportation Committee June 7, 2019 From: PIO To: Clerk of the Board Subject: FW: South 125 to East 94 interchange Date: Friday, May 31, 2019 12:22:51 PM -----Original Message----- From: KEITH CLEMENTS <[email protected]> Sent: Friday, May 31, 2019 10:51 AM To: PIO <[email protected]> Subject: South 125 to East 94 interchange I would like to let you know that I am very much in favor of finishing the SR 125 south to SR 94 West interchange, so that we have a freeway to freeway connection. This is a LONG overdue project and needs to be completed as soon as possible. The congestion is a major problem during all hours of the day and really needs be addressed in the next year. I understand that funds are available to do this project and need to be earmarked to complete the connection. Thank you, Keith Clements La Mesa, CA This Relates to Agenda Item No. 2 Transportation Committee June 7, 2019 From: james rue To: Huntington, Susan; Clerk of the Board Cc: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] Subject: SanDag miss use of our TAXes Date: Sunday, June 02, 2019 7:06:34 PM Hello SANDAG I'm in fear of misuse of our tax dollars by SANDAG, and I would like my opinion heard. For more than 30 years I commuted to/from downtown San Diego, I drove, I car pulled, and commuted using public transportation (bus & trolley). -

Building North Carolina's Offshore Wind Supply Chain the Roadmap for Leveraging Manufacturing and Infrastructure Advantages

Building North Carolina's Offshore Wind Supply Chain The roadmap for leveraging manufacturing and infrastructure advantages March 2021Subtitle Copyright This report and its content is copyright of BVG Associates LLC - © BVG Associates 2021. All rights are reserved. Disclaimer This document is intended for the sole use of the Client who has entered into a written agreement with BVG Associates LLP (referred to as “BVGA”). To the extent permitted by law, BVGA assumes no responsibility whether in contract, tort including without limitation negligence, or otherwise howsoever, to third parties (being persons other than the Client) and BVGA shall not be liable for any loss or damage whatsoever suffered by virtue of any act, omission or default (whether arising by negligence or otherwise) by BVGA or any of its employees, subcontractors or agents. A Circulation Classification permitting the Client to redistribute this document shall not thereby imply that BVGA has any liability to any recipient other than the Client. This document is protected by copyright and may only be reproduced and circulated in accordance with the Circulation Classification and associated conditions stipulated in this document and/or in BVGA’s written agreement with the Client. No part of this document may be disclosed in any public offering memorandum, prospectus or stock exchange listing, circular or announcement without the express and prior written consent of BVGA. Except to the extent that checking or verification of information or data is expressly agreed within the written scope of its services, BVGA shall not be responsible in any way in connection with erroneous information or data provided to it by the Client or any third party, or for the effects of any such erroneous information or data whether or not contained or referred to in this document. -

Excursions from Ferrol 7

Ferrol tourist office Panoramic view Bike station URBAN & CULTURAL Tourist Office Restaurants area Bike rental Hotel accomodation Shopping area Bike lane Boats Ferrol estuary Taxi Walk Start of Saint James Tourist train Transfer station Way Religious building Cruise ships Saint James Way Start of pilgrimage Museum/ culture Car park route to San Andrés de Teixido Modernism Petrol station Ferrol Tourist Office Magdalena, 56 - T 981 944 272 Tourist Information Point Peirao de Curuxeiras Beach For children www.ferrol.es/turismo [email protected] Find out more! Published by: Arquivo Turgalicia, Arquivo Turismo de Santiago, Sociedade Mixta de Turismo de Ferrol Arquivo Centro Torrente Ballester Produced by: Layout: Gráficas de Cariño, S.L. Item-Aga Photography: Translated by: Ovidio Aldegunde, Juan Balsa, José Balsa, Adolfo Linkinter Enríquez, Xurxo Lobato,María López Faraldo, Margen Fotografía (Alberto Suárez/Tino Viz), Legal deposit: C 1039-2011 Please note that All information supplied in this brochure is subject to change and is based on the information avai - lable at the time of going to press. Turismo de Ferrol cannot be held responsible for any future chan - ges. Please contact Turismo de Ferrol to obtain the latest information. 0 Table of contents and credits 1 · 10 reasons to visit Ferrol............................ ....................................... 01 2 · Walks ................................................................................................. 07 3 · 48 hours in Ferrol .............................................................................. -

Security & Defence European

a 7.90 D European & Security ES & Defence 6/2016 International Security and Defence Journal COUNTRY FOCUS: SPAIN Close-In Ship Defence ISSN 1617-7983 • www.euro-sd.com • Training and Simulation A Fighter for the Information Age Current trends and international programmes F-35 LIGHTNING II status report November 2016 Politics · Armed Forces · Procurement · Technology job number client contact 00684_218_IDEX2017 September Print Ads_Euroatlantic Defence News, West Africa Security & Greek Defence News IDEX Joenalene final artwork size colour designer proof print ready 210mm (w) x 297mm (h) CMYK Tina 1 Y idexuae.ae The Middle East and North Africa’s largest defence and security exhibition returns to Abu Dhabi in February 2017. The global defence industry will continue to meet influential VIP’s, decision makers, military personnel and key investors at IDEX 2017. Attracting more than 1,200 exhibitors and 101,000 local, regional and international trade visitors and officials from government industry and armed forces. For detailed information about IDEX 2017, please visit www.idexuae.ae To book an exhibition stand or outdoor space, please email [email protected] 19-23FEBRUARY2017 ADNEC,ABUDHABI,UAE StrategicPartner PrincipalPartner Organisedby HostVenue Inassociationwith Editorial Afghanistan Needs More Support At the present time all eyes are on the Ban Ki Moon called for “a strong message war in Syria, and the despairing efforts of support for the people and the govern- to achieve at least a temporary ceasefire. ment of Afghanistan”. This is causing another war zone almost On 16 October 2016 the EU and the to disappear from public notice: Afghani- government in Kabul agreed to speed up stan. -

NAVIRIS and NAVANTIA SIGN a Mou for the EUROPEAN PATROL CORVETTE PROGRAM

NAVIRIS AND NAVANTIA SIGN A MoU FOR THE EUROPEAN PATROL CORVETTE PROGRAM Genoa/Madrid, February 11, 2021 – NAVIRIS, the 50/50 joint venture company between Fincantieri and Naval Group in charge of development of cooperation programs, and NAVANTIA have signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) aimed at enlarging the industrial cooperation for the European Patrol Corvette (EPC) program, the most important naval initiative within the Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) project. The EPC will be a smart, innovative, affordable, sustainable, interoperable and flexible vessel to meet the future missions in the evolved world context of mid-21st century. EPC will be a fully ready surface combatant to carry-out diversified missions, primarily aimed at enhancing maritime situational awareness, surface superiority and power projection, particularly in the context of governmental peacetime actions, such as those aimed at counteracting piracy and smuggling, as well as those actions dedicated to humanitarian assistance, migration control and aimed at ensuring freedom of navigation. It will be about 100 meters and 3.000 tons, able to replace in the near future (from 2027 onward) several classes of ships, from patrol vessels to light frigates. The design requirements for these vessels, with a clear objective of commonality of solutions and modularity for adaptation to national requirements, are expected from the Navies in 2021. On the industrial side, NAVIRIS and NAVANTIA will act in a fully coordinated way with Fincantieri and Naval Group for the EPC program. The studies could potentially benefit from European Union and national funds and will include a large part of R&D leading to innovative solutions for making easier the co-development and interoperability, the efficiency of the vessels in operations and the digital data management. -

![[No.]: [Chapter Title]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2488/no-chapter-title-2732488.webp)

[No.]: [Chapter Title]

2 Europe United Kingdom Plymouth 2.1 The delegation visited the Babcock/Royal Naval Dockyard Devonport 2.2 Babcock explained to the delegation that their role was very much as a service provider, not a traditional Original Equipment Manufacturer (OEM). This meant that Babcock had long term contracts with a very small number of customers. It was a successful model, noting that Babcock was now the major supplier to the UK Ministry of Defence (MoD). 2.3 Babcock explained their role in surface ships construction and support, and provided background to the consolidation process that had been taking place in UK dockyards. This is part of a UK Government policy to create an indigenous support capability. 2.4 The Babcock presentation explained the split between BAE Systems and Babcock in construction and support, with BAE Systems being the builder of submarines and Babcock the support contractor. It was noted this distinction is less clear cut for surface ships, with Babcock involved in some construction work and BAE Systems involved in some support work. 2.5 The delegation was interested in how this ‘single source’ approach, worked for the UK. Rear Admiral Lloyd stated that the UK has no other option – there is no alternative capability available and the UKMOD knows it has to deal with this situation. Babcock and BAE Systems are seen an integral parts of the ‘strategic enterprise’ of shipbuilding and 10 support. This is in part driven by the overheads of establishing and maintaining the required technical expertise. 2.6 Babcock explained to the delegation that, given the life-cycle from start of first boat to the disposal of the last, submarines required a fifty year program plan. -

Study on Competitiveness of the European Shipbuilding Industry

Ref. Ares(2015)2238291 - 29/05/2015 Study on Competitiveness of the European Shipbuilding Industry Within the Framework Contract of Sectoral Competitiveness Studies – ENTR/06/054 Final report Client: Directorate-General Enterprise & Industry Rotterdam, 8 October 2009 2 ECORYS SCS Group P.O. Box 4175 3006 AD Rotterdam Watermanweg 44 3067 GG Rotterdam The Netherlands T +31 (0)10 453 88 16 F +31 (0)10 453 07 68 E [email protected] W www.ecorys.com Registration no. 24316726 ECORYS Macro & Sector Policies T +31 (0)31 (0)10 453 87 53 F +31 (0)10 452 36 60 Study on the Competitiveness of the European Shipbuilding Industry – 2009 1 Study on the Competitiveness of the European Shipbuilding Industry – 2009 2 Table of contents Executive Summary 7 1 Introduction 18 1.1 Background and objective 18 1.2 Some notions on data availability 18 1.3 Report structure 20 PART I: Sector description 21 2 World shipbuilding: key characteristics and trends 22 2.1 Sector definition 22 2.2 The global market place of shipbuilding 23 2.2.1 Ship construction and repair – changing regional production patterns 24 2.2.2 Marine equipment 35 2.2.3 Naval shipbuilding 38 2.3 Shipbuilding market cycles and worldwide trends 39 2.3.1 Shipbuilding is a cyclic industry 39 2.3.2 Were we entering the next down cycle? 41 2.3.3 The current economic and financial crisis 44 2.4 The structure of shipbuilding by main region 51 2.4.1 Europe 52 2.4.2 South Korea 71 2.4.3 China 74 2.4.4 Japan 76 2.4.5 Emerging shipbuilding nations 78 2.5 Conclusions 84 PART II: Analysis of competitive position -

Strategic Research Agenda

WATERBORNE TP has been set up as an industry-oriented Technology Platform to establish a continuous dialogue between all waterborne stakeholders, such as classification societies, energy companies, infrastructural companies, environmental STRATEGIC non-profit organisations, manufacturers, research institutes, shipyards, ship-owners, waterway and port operators, universities, fisheries and citizen associations, as well as RESEARCH AGENDA European Institutions and Member States. for the European Waterborne Sector January 2019 WATERBORNE TP c/o SEA Europe Rue de la Loi, 67 (4th floor) B-1000, Belgium +32 2 230 2791 [email protected] www.waterborne.eu GENERAL SCENARIO 2050 FOR MISSIONS OF PROGRESS AND LIST OF MEMBERS INTRODUCTION THE WATERBORNE SECTOR THE WATERBORNE SECTOR ACHIEVEMENTS DEFINITIONS RESEARCH Sintef Ocean Marin Balance Fundación Centro CNR TNO Bulgarian Ship Tecnológico Soermar Hydronomics Centre Fundacíon Valenciaport CONTENT GENERAL Aimen Technology Centre Centre for Research Cetena S.p.a. andTechnology Hellas Fondazione CS Mare Center of Maritime Technologies GENERAL INTRODUCTION 2 INTRODUCTION INDUSTRIAL Fincantieri Meyer Werft Shipyard Lloyd’s Register Prisma Electronics SCENARIO 2050 The ability of society and industry to With more than 70% of the globe covered by water, a view to contributing to the strategy for a European Group 50% of Europeans living close to the coast and the long-term vision for a prosperous, modern, competitive Rina Services Spa DNVGL The European Inland FOR THE WATERBORNE SECTOR 4 address global and regional challenges, Rolls-Royce plc Eekels Technology B.V. Bureau Veritas Waterway Transport valleys of the 15 largest rivers, the Waterborne sector2 and climate neutral economy5, as well as to the GHG Platform to meet the UN Sustainable Development Navantia Factorias Vulcano MAN Diesel & Turbo European economy and society 6 will be pivotal in the coming decades, both in Europe Strategy of the International Maritime Organization4 Wärtsilä Netherlands B.V. -

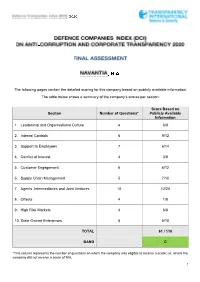

The Following Pages Contain the Detailed Scoring for This Company Based on Publicly Available Information

The following pages contain the detailed scoring for this company based on publicly available information. The table below shows a summary of the company’s scores per section: Score Based on Section Number of Questions* Publicly Available Information 1. Leadership and Organisational Culture 4 6/8 2. Internal Controls 6 9/12 3. Support to Employees 7 6/14 4. Conflict of Interest 4 3/8 5. Customer Engagement 6 6/12 6. Supply Chain Management 5 7/10 7. Agents, Intermediaries and Joint Ventures 10 12/20 8. Offsets 4 1/8 9. High Risk Markets 4 6/8 10. State-Owned Enterprises 5 5/10 TOTAL 61 / 110 BAND C *This column represents the number of questions on which the company was eligible to receive a score; i.e. where the company did not receive a score of N/A. 1 1. Leadership and Organisational Culture Question 1.1. Does the company have a publicly stated anti-bribery and corruption commitment, which is authorised by its leadership? Score 0 Comments There is no evidence that the company publishes a commitment to ethical or anti-bribery and corruption standards that is authorised and endorsed by the company’s leadership. Although the company’s Code of Business Conduct reflects a commitment to high business standards, this is not supported by a public statement from the company’s leadership and therefore the company receives a score of ‘0’. Evidence [2] Anti-Corruption Manual (Document) Accessed 06/08/2019 https://www.navantia.es/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/manual-anticorrupcion_julio-2019_ingles_baja.pdf [p.44] Chapter 13 Approval The present Manual, as well as the Anti-Corruption Policy (Appendix IV), were approved by NAVANTIA’s Board of Directors in the meeting held on June 20th, 2018, and may be modified in order to adequately monitor and control NAVANTIA’s transactions at all times to minimize the probability of criminal risks related to corruption.