History 391E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HIST 3801E: the Historian's Craft 2019-20

HURON UNIVERSITY COLLEGE HIST 3801E: The Historian's Craft 2019-20 Dr. Amy Bell [email protected] Office V130 Office hours: Thursdays 9:30-11:15 or by appt. Class meets: Tuesdays 8:30-10:30 and Thursdays 8:30-9:30 in HUC W106 Introduction: Truth, Archives and Phantoms History 3801E is a seminar course that tries to answer two questions: what is History, and why does it matter? As one of the few required courses in your History module at Huron, The Historian’s Craft is a capstone in your career as a History student, but it also asks you to question and evaluate the way you understand other aspects of your undergraduate work, and your experience outside the boundaries of academic study. Who creates knowledge? How is it used or misused? What is true, how do we know, and what do we do in the face of the limits of knowledge? What gets left out of our accounts of the past, and how do we recognize these phantoms haunting the present? Most History students go on to pursue careers outside the ranks of academic historians, so while the course is concerned with historical method, it is also much broader in its application. We will work in a practical way with the materials of History, and will consider the sea-changes of postmodernism, new studies in Public History, and cultural studies of historical memory. The course also considers the place of History in the emerging field of the digital humanities, and gives you experience in that field. Class Field Work and Community-based Research Project The centerpiece of 3801E is a community-based and experiential research project that brings together the theoretical and practical aspects of the course material. -

Senior School 2020-2021

SENIOR SCHOOL OVERVIEW 2020-2021 BUILDING FINE YOUNG MEN. ONE BOY AT A TIME. ST. GEORGE’S SCHOOL is a strong academic university preparatory institution with selective entrance standards. Offering a Boarding Program for Grades 8 to 12 and a Day Program for Grades 1 to 12, St. George’s is committed to its Mission of building fine young men. The School encourages the pursuit of excellence in all endeavours, and is committed to the healthy growth of body, mind, and spirit. Character development, leadership, and service opportunities are integral to the School’s mission. Descriptions reflect typical St. George’s School offerings over the past five years. Current and future offerings may differ based on evolving programs and adjustments related to Covid19. A WELL-DESERVED REPUTATION OUR ACADEMIC PROFILE St. George’s reputation as one of the most academically challenging and competitive high school environments in Canada is long- standing. As a university preparatory institution with selective entrance standards, our students meet that challenge by earning exemplary grades, as evidenced by the extraordinary number of 160 university acceptances from around the globe. All of our graduates STUDENTS leave St. George’s School with options; our goal is to prepare them IN THE 2019 GRADUATING CLASS sufficiently well in all respects to ensure that the choices they have upon graduation will set them on a path to lifelong success. 100% OF ST. GEORGE’S GRADUATES RECEIVE POST-SECONDARY ADMISSION $1.5M IN MERIT-BASED SCHOLARSHIPS AWARDED TO THE CLASS OF 2019 1275 773 APPLICATIONS ACCEPTANCES SUBMITTED TO FROM 174 142 DIFFERENT DIFFERENT UNIVERSITIES UNIVERSITIES WORLD-WIDE IN CANADA, ASIA, THE UK, (AN AVERAGE OF 8 APPLICATIONS/STUDENT) INDIA, EUROPE AND THE U.S. -

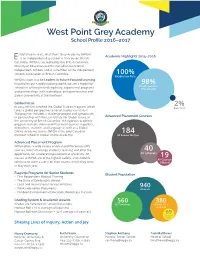

West Point Grey Academy School Profile 2016–2017

West Point Grey Academy School Profile 2016–2017 stablished in 1996, West Point Grey Academy (WPGA) Academic Highlights 2015–2016 E is an independent day school in Vancouver, British Columbia. WPGA is accredited by the British Columbia Ministry of Education and the Canadian Accredited Independent Schools and is a member of the Independent Schools Association of British Columbia. raduation Rate WPGA’s vision is to be Leaders in Future-Focused Learning. Inspired by our rapidly evolving world, we are a model for ostsecondary schools in offering interdisciplinary, experiential programs lacements and partnerships, with technology, entrepreneurship and global connectivity at the forefront. Global Focus In 2014, WPGA launched the Global Studies Program, which ap ear takes a global perspective to social studies curriculum. The program includes a challenge project and symposium in partnership with the Liu Institute for Global Issues at Advanced Placement Courses the University of British Columbia; the rigorous academic program includes Advanced Placement courses in politics, economics, statistics and language as well as a Global Online Academy course (WPGA is the only Canadian 184 member school in Global Online Academy). A ams ritten Advanced Placement Program WPGA offers a wide variety of Advanced Placement (AP) courses, which challenge students’ learning and offer the 40 opportunity for accelerated placement at university. AP A Scholars classes at WPGA are of the highest calibre, and students continue to score a 4 or 5 on their exams, which they write in May each year. Flagship Programs for Senior Students Student Population • First Responders Medical Training • The Duke of Edinburgh’s Award • Local and International Service Initiatives • Work Experience Placements Students • Outdoor Environmental Education; Wilderness Pursuits Grading System & Academic Awards 560 380 Grades are reflected on school transcripts. -

CORPORATE FINANCE – MOS 3310B 550 Course Outline Winter 2020

MANAGEMENT AND ORGANIZATIONAL STUDIES CORPORATE FINANCE – MOS 3310B 550 Course Outline Winter 2020 CONTACT INFORMATION Instructor: Srikanth Ramani Faculty of Arts and Social Science Office: A2B, Huron Admin Asst: Kathy Mazur-Spitzig Phone: 519-438-7224 #231 Phone: : 519-438-7224 #883 Huron Office: A116 Email: [email protected] Office Hours: Before / After class MOS Director: Jan Klakurka Or by appointment Wed 1-3pm Office: A2C Email: [email protected] Phone: 519-438-7224 #263 Email: [email protected] Web: OWL2 (owl.uwo.ca) Timetable Wednesday 2:30 – 5:30 pm Class Room: V210 Course Prerequisites Business 2257 and enrolment in the BMOS Program or Major in Finance Anitirequisite: MOS 2310 Course Materials Brealey, R. Mayers, C. Marcus, A.J. Manes, E.M. and Mitra D. Fundamentals of Corporate Finance, Sixth Canadian Edition, Toronto, McGraw-Hill, ISBN: 13: 978-125902496-2 Supplemental Materials (on-line and/or library) Periodicals: Globe and Mail, Wall Street Journal, Financial Times, Bloomberg Business Week, Economist, etc. Finance Related Web Sites (for reference and research) Government • Department of Finance Canada www.fin.gc.ca • Bank of Canada www.bankofcanada.ca Finance • Bloomberg www.bloomberg.com • Thomson Reuters www.thomsonreuters.com • Yahoo finance.yahoo.com • FinViz www.finviz.com • Morningstar www.morningstar.ca Huron University College, Affiliate of The University of Western Ontario MOS 3310A 550 Summer Intersession 2019 Education • CFA Institute www.cfainstitute.org • Canadian Securities institute www.csi.ca Course Objectives This course is designed to provide a broad overview of issues in financial management and corporate finance. You will learn how financial managers make investment, financing and other decisions and what kind of financial tools and methods they use to make decisions. -

DAP Proposal for New 2Nd Year History Course on European

1 History 4702F European Imperialism Huron University College/History Department Seminars, Wednesdays 10:30-1:20, W101 Course Director: Dr. Geoff Read Office: A217 Office hours: Wednesdays, 9:30-10:30, Thursdays, 2:30-3:30, Fridays, 11:30-12:30 E-mail: [email protected] Telephone: 519-438-7224 x222 Prerequisite(s): 2.0 courses in History at the 2200 level of above, or permission of the department. Course Description and Rationale: This course begins with a discussion of theories of imperialism and an overview of the early modern European empires. It ends with post-Word War Two decolonization. In between the class will explore major themes in the topic including expansion, governance, gender, and resistance. Students are expected to attend 3 hours of seminar every week. Attendance will be taken at all classes (see below); you are also responsible for all the material covered during classes on the take- home exam. Most of the in-class time will be spent either discussing class materials or with student presentations; however, there will be lectures when necessary to cover the necessary historical context. The lectures will not be posted on-line and the professor will not provide his lecture notes to students. As this is a seminar and discussion of class materials is the main focus of the class, it is essential that you complete the assigned reading before attending class. In order to attain a top mark for participation you will have to participate regularly and actively in these discussions. Failure to attend 50% of the seminars will result in a participation grade of zero. -

Meeting of the OCUFA Status of Women and Equity Committee February 8, 2019

Meeting of the OCUFA Status of Women and Equity Committee February 8, 2019 1. Table of Contents Page 1 2. Meeting Agenda Page 2 3. Registration List Page 3-4 4. SWEC Mandate Page 5-6 5. SWEC Ground Rules Page 7 6. September 2018 Meeting Minutes Page 8-11 7. Chair’s Report Page 12-13 8. OCUFA President Report Page 14-24 9. Workshop Materials Page 25-36 a. Backgrounder on government announcements related to the PSE sector b. OCUFA letters and statements 1 Meeting of the OCUFA Status of Women and Equity Committee February 8, 2019 Agenda 8:00 a.m. Breakfast Please note that there will be a hot buffet breakfast served at 8am in the meeting room. This is a great opportunity for folks to connect with each other about what is happening on your campuses. 9:00 a.m. Welcome and Introductions 9:15 a.m. Land Acknowledgment 9:25 a.m. Approval of Agenda Approval of Minutes Business arising from the minutes 9:35 a.m. Report of OCUFA Executive and Board 9:50 a.m. Report of SWEC Chair 10:25 a.m. Report of the SWEC vice Chair 10:30 a.m. Break 10:45 a.m. Member reports 11:45 a.m. Wrap up Other Business 12:00 p.m. Lunch 1:00 p.m. Workshop – Responding to Ford’s anti-equity agenda 2:15 p.m. Break 2:30 p.m. Workshop - continued 4:30 p.m. Adjourn 2 OCUFA Status of Women and Equity Committee Meeting Friday February 8, 2019 Pier 4/5 Room Westin Harbour Castle, Toronto List of Participants Algoma Anthony Fabiano Brescia Helene Cummins Brock Debra Harwood Huron Donna Kotsopoulos Interpreter Angela Core Interpreter Sean Power King’s Cathy Chovaz Lakehead Karen Poole Laurentian Reuben Roth Nipissing Sal Renshaw Nipissing Lanyan Chen OCUFA Staff Cheryl Athersych OCUFA Staff Abe Nasirzadeh OCUFA Staff Mina Rajabi Paak OCUFA President Gyllian Phillips Ottawa Kathryn Trevenen Queen’s Leslie Jermyn 3 Ryerson Rachel Berman Toronto Azita Taleghani Trent Michele McIntosh UOIT Elita Partosoedarso Waterloo Weizhen Dong Wilfrid Laurier Rebecca Godderis Windsor Brandi Lucier York Ellie Perkins 4 Status of Women and Equity Committee Mandate (Section 22 of the OCUFA Bylaws) a. -

The Americas

APPROVED HOST UNIVERSITIES & PROGRAMS (Arts) University/ Institution Name Courses and programs Full-time course load per Type of study acceptable for transfer Fall or Winter Term abroad credits:ON CAMPUS (Equivalent to 15 credits at available: courses ONLY unless McGill) otherwise indicated ** based on information Exchange only available at time of publication (E), Independent * All online courses must be and is subject to change. approved by the Associate study away only Dean of Arts. For (ISA) or Both (E procedures refer to: & ISA) http://www.mcgill.ca/oasis/away/ online-education THE AMERICAS ARGENTINA Pontificia Universidad Catolica Range of 15 to 18 creditos ISA Argentina Universidad de Belgrano 5 courses ISA Universidad de Buenos Aires Spanish language certificate 2 6-horas-par-semana ISA program NOT APPROVED courses is equal to 12 for credit transfer credits Universidad del Salvador 5 courses E & ISA BRAZIL Centro Universitario Feevale 5 courses ISA Pontificia Universidade Catolica 15 credits ISA do Rio de Janeiro Universidade de Sao Paulo TBA ISA Universidade Federal do Rio 18 to 24 créditos (TBC) ISA Grande do Sol CANADA Acadia University Online courses * 15 credit hours ISA Athabasca University Onine courses * Full course load is defined ISA as two credits per month Brandon University 15 credits ISA Brock University 2.5 credits ISA Canadian Mennonite University 15 credits ISA Capilano College 15 credits ISA Carleton University 2.5 credits ISA Dalhousie University 15 credit hours ISA Huron University College 2.5 units ISA King's -

Proposal for a New Conjoint Master of Arts in Theological Studies, Toronto School of Theology

FOR RECOMMENDATION PUBLIC OPEN SESSION TO: Committee on Academic Policy and Programs SPONSOR: Sioban Nelson, Vice-Provost, Academic Programs CONTACT INFO: (416) 978-2122, [email protected] PRESENTER: See Sponsor CONTACT INFO: DATE: March 11, 2016 to March 30, 2016 AGENDA ITEM: 1 ITEM IDENTIFICATION: Proposal for a new conjoint Master of Arts in Theological Studies, Toronto School of Theology JURISDICTIONAL INFORMATION: The Committee on Academic Policy and Programs has the authority to recommend to the Academic Board for approval new graduate programs and degrees. (AP&P Terms of Reference, Section 4.4.a.ii) GOVERNANCE PATH: 1. Committee on Academic Policy and Programs [for recommendation] (March 30, 2016) 2. Academic Board [for approval] (April 21, 2016) 3. Executive Committee [for confirmation] (May 9, 2016) PREVIOUS ACTION TAKEN: The proposal for the conjoint Master of Arts in Theological Studies received approval from the Toronto School of Theology Academic Council on March 4, 2016. HIGHLIGHTS: This is a proposal for a new research master’s program in Theological Studies. The proposed M.A. will be offered conjointly by the University of Toronto (U of T) and the Toronto School of Theology (TST). Page 1 of 3 Committee on Academic Policy and Programs – Proposal for conjoint M.A. in Theological Studies Background TST and the seven theological colleges associated with it are institutionally independent of U of T and have their own systems of governance. The relationship between U of T and TST arose as follows: Whereas European universities from their founding included the offering of degrees in theology as one of their roles, historically, U of T’s charter did not include the power to grant degrees in theology. -

Huron University College

Huron University College Philosophy 4851G Section 550 Philosophy of Law: Free Speech on Campus Monday 11:30 AM-12:30 PM; Thursday 11:30 AM-1:30 PM HUC W106 Course Outline Winter 2019 Instructor: Dr. D. Conter Office: V 131 Office Hours: Monday 8:30 AM-11:30 AM; Thursday 10:30 AM-11:30 AM E-mail: [email protected] 438-7224 x253 Description In 2019, the course will focus on the regulation of expression or speech on college and university campuses. A distinction will be drawn between the constitutional guarantee that prohibits the legal regulation of some kinds of speech on the campuses of some colleges and universities, and the broader non-legal ideal of freedom of expression that – controversially – some people feel should protect controversial expression on campuses. General topics will include: general philosophical arguments in favour of freedom of expression; arguments against censorship; the historical expansion of freedom of expression; and the harms associated with some kinds of expression. More specific issues to be dealt with will be: the protection public commentary by professors on political matters which may reflect back unfavourably on their own institutions; student engagement in social media, particularly when their postings have content related to sex or gender; hate speech involving race, religion, or ethnicity; group libel; threats; harassment; micro-aggressions; safe spaces; the powers of university governing bodies; and policy recommendations. Objectives Students will learn to assess the seriousness of the philosophical issues that arise in connection with the legal ideal of freedom of expression or speech. In addition, they will develop the skills to make comparative assessments of various treatments to these problems offered by philosophers, lawyers, judges, and university administrators mostly working mainly in the last 10 years or so. -

Ouinfo 2019–2020 1 Table of Contents

Last Updated: September 10, 2019 | OUInfo 2019–2020 1 Table of Contents Western University – Huron University College .....................................................303 Table of Contents Western University – King's University College .....................................................304 Wilfrid Laurier University – Brantford Campus.......................................................305 About OUInfo ............................................................................. 4 Wilfrid Laurier University – Waterloo Campus .......................................................305 University of Windsor .............................................................................................306 Subject Area Chart .................................................................... 5 York University .......................................................................................................306 Degree Abbreviations................................................................................................ 5 York University – Glendon Campus .......................................................................307 Common Course Codes.......................................................... 18 Campus Visits and Events ................................................... 308 Algoma University ..................................................................................................308 Admission Guidelines and Programs of Study .................... 19 Brock University .....................................................................................................308 -

Seminary Academic Catalogue

SEMINARY ACADEMIC CATALOGUE 2019 – 2020 Equipping the Church to Engage the World Seminary Ac ademic Catalogue | 1 ADMISSIONS TEAM Karyn Mowbray Seminary Admissions Coordinator [email protected] Theresa Beach Registrar & Director of Admissions [email protected] Brad Hooper Seminary Admissions Counsellor [email protected] DiscoverHeritage.ca [email protected] 1•800•465•1961, ext. 244 1•519•651•2869, ext. 244 TABLE OF CONTENTS Admissions Team 1 About Heritage Seminary 3 Mission Statement 3 Vision 3 Values 3 Our Identity 4 Doctrinal Statement 4 History 6 Affiliations 6 Accreditation 6 Board of Directors 7 Student Life 8 Housing 8 Food Services 9 Library 9 Book Room 9 Administration and Faculty 10 Administration 10 Core Faculty 10 Part-Time Faculty 10 Adjunct Faculty 11 Academic Information 13 Admissions 13 Academic Policies 15 Graduation 17 Awards 18 Financial Information 19 Payment of Accounts 19 Refunds 19 Financial Assistance 19 Scholarships 20 Heritage Bursary 20 PROGRAMS 21 Master of Divinity 21 Master of Theological Studies 24 Graduate Diploma in Pastoral Studies 26 Graduate Certificate of Theological Studies 27 Graduate Certificate in Biblical Preaching 28 Graduate Certificate for Women in Ministry 29 Graduate Certificate in Biblical Care and Counselling……………….30 Course Descriptions 31 Research Methods 31 Language Studies 31 Biblical Studies 31 Old Testament Studies 32 New Testament Studies 33 Theological Studies 33 Historical Studies 35 Pastoral & Leadership Studies 36 Counselling Studies………………………………………………37 Preaching Studies 38 Intercultural Studies 38 Spiritual Formation Studies 39 Internships 39 Seminary Ac ademic Catalogue | 3 ABOUT HERITAGE SEMINARY MISSION STATEMENT The mission of Heritage Seminary is to equip people for theologically grounded leadership and ministry to serve the mission of God in the world through their involvement in evangelical churches, denominations, and parachurch ministries. -

Politique De Surveillance D'examen

Politique de surveillance d’examen Auteure : Directrice exécutive, Processus opérationnels et normes de service Approuvée par : Maxim Jean-Louis, Président – Directeur général Approuvée : 1 février 2018 Date en vigueur : 12 février 2018 Table des matières Objet et portée .............................................................................................................. 3 Responsabilités ............................................................................................................. 5 1. Les responsabilités de Contact North | Contact Nord ............................................... 5 2, Les responsabilités des surveillantes et surveillants ................................................. 5 3 Les responsabilités des établissements d’enseignement approuvés ......................... 6 4. Les responsabilités des étudiantes et étudiants ...................................................... 6 Définitions ..................................................................................................................... 7 La Politique ..................................................................................................................10 1. Les établissements d’enseignement où les étudiantes et étudiants, pour lesquels des services d’examen sont fournis ......................................................................................10 2. La malhonnêteté intellectuelle et la conduite d’examen inappropriée .......................11 3. Les accommodements pour les étudiantes et étudiants ayant des