The Port of Virginia: a Primer the PORT of VIRGINIA: a PRIMER

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Container Ship Size and Port Relocation Discussion Paper 169 Roundtable

CPB Corporate Partnership Board Container Ship Size and Port Relocation Discussion Paper 169 Roundtable Olaf Merk International Transport Forum CPB Corporate Partnership Board Container Ship Size and Port Relocation Discussion Paper 169 Roundtable Olaf Merk International Transport Forum The International Transport Forum The International Transport Forum is an intergovernmental organisation with 59 member countries. It acts as a think tank for transport policy and organises the Annual Summit of transport ministers. ITF is the only global body that covers all transport modes. The ITF is politically autonomous and administratively integrated with the OECD. The ITF works for transport policies that improve peoples’ lives. Our mission is to foster a deeper understanding of the role of transport in economic growth, environmental sustainability and social inclusion and to raise the public profile of transport policy. The ITF organises global dialogue for better transport. We act as a platform for discussion and pre- negotiation of policy issues across all transport modes. We analyse trends, share knowledge and promote exchange among transport decision-makers and civil society. The ITF’s Annual Summit is the world’s largest gathering of transport ministers and the leading global platform for dialogue on transport policy. The Members of the Forum are: Albania, Armenia, Argentina, Australia, Austria, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Belgium, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Canada, Chile, China (People’s Republic of), Croatia, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Georgia, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, India, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Kazakhstan, Korea, Latvia, Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Mexico, Republic of Moldova, Montenegro, Morocco, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russian Federation, Serbia, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, Ukraine, the United Arab Emirates, the United Kingdom and the United States. -

Audit Template for Inland Port Sustainability Our Mission

Kentucky Transportation Center Research Report KTC -14-11/MTIC1-14-1F Audit Template for Inland Port Sustainability Our Mission We provide services to the transportation community through research, technology transfer and education. We create and participate in partnerships to promote safe and effective transportation systems. © 2014 University of Kentucky, Kentucky Transportation Center Information may not be used, reproduced, or republished without our written consent. Kentucky Transportation Center 176 Oliver H. Raymond Building Lexington, KY 40506-0281 (859) 257-4513 fax (859) 257-1815 www.ktc.uky.edu Audit Template for Inland Port Sustainability Prepared for: Multimodal Transportation & Infrastructure Consortium by the Kentucky Transportation Center 11/21/2014 This Page Left Intentionally Blank. Audit Template for Inland Port Sustainability Authors: Principal Investigator: Doug Kreis, PE, MBA, PMP Researcher(s): Sarah McCormack, MSc, CTL Research Engineer Christopher Van Dyke, MA Research Analyst Bryan Gibson, PhD Research Associate Multimodal Transportation and Infrastructure Consortium P.O. Box 5425 Huntington, WV 25703-0425 Phone: (304) 696-2313 • Fax: (304) 696-6088 Disclaimer: The contents of this report reflect the views of the authors, who are responsible for the facts and the accuracy of the information presented herein. This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the U.S. Department of Transportation’s University Transportation Centers Program, in the interest of information exchange. The U.S. Government assumes -

Digitalizing the Port Call Process

UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT TRANSPORT AND TRADE FACILITATION Series No 13 Digitalizing the port call process UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT TRANSPORT AND TRADE FACILITATION Series No 1 Digitalizing the port call process Geneva, 2020 DIGITALIZING THE PORT CALL PROCESS © 2020, United Nations This work is available open access by complying with the Creative Commons licence created for intergovernmental organizations, available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo/. The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations or its officials or Member States. The designation employed and the presentation of material on any map in this work do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Photocopies and reproductions of excerpts are allowed with proper credits. This publication has not been formally edited. United Nations publication issued by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. UNCTAD/DTL/TLB/2019/2 eISBN: 978-92-1-004933-7 UNCTAD Transport and Trade Facilitation Series No. 13 ൟ2 DIGITALIZING THE PORT CALL PROCESS Acknowledgements This study has been compiled by Mikael Lind, Robert Ward, Michael Bergmann, Sandra Haraldson, and Almir Zerem with the Research Institutes of Sweden (RISE), in cooperation with Jan Hoffmann, chief of the Trade Logistics Branch, Division on Technology and Logistics, building upon related discussion and presentations by Mikael Lind at the UNCTAD Multi-Year Expert Meeting on Transport, Trade Logistics and Trade Facilitation in its sixth session on 21 to 23 November 2018. -

Basic Concepts of Maritime Transport and Its Present Status in Latin America and the Caribbean

or. iH"&b BASIC CONCEPTS OF MARITIME TRANSPORT AND ITS PRESENT STATUS IN LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN . ' ftp • ' . J§ WAC 'At 'li ''UWD te. , • • ^ > o UNITED NATIONS 1 fc r> » t 4 CR 15 n I" ti i CUADERNOS DE LA CEP AL BASIC CONCEPTS OF MARITIME TRANSPORT AND ITS PRESENT STATUS IN LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN ECONOMIC COMMISSION FOR LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN UNITED NATIONS Santiago, Chile, 1987 LC/G.1426 September 1987 This study was prepared by Mr Tnmas Sepûlveda Whittle. Consultant to ECLAC's Transport and Communications Division. The opinions expressed here are the sole responsibility of the author, and do not necessarily coincide with those of the United Nations. Translated in Canada for official use by the Multilingual Translation Directorate, Trans- lation Bureau, Ottawa, from the Spanish original Los conceptos básicos del transporte marítimo y la situación de la actividad en América Latina. The English text was subse- quently revised and has been extensively updated to reflect the most recent statistics available. UNITED NATIONS PUBLICATIONS Sales No. E.86.II.G.11 ISSN 0252-2195 ISBN 92-1-121137-9 * « CONTENTS Page Summary 7 1. The importance of transport 10 2. The predominance of maritime transport 13 3. Factors affecting the shipping business 14 4. Ships 17 5. Cargo 24 6. Ports 26 7. Composition of the shipping industry 29 8. Shipping conferences 37 9. The Code of Conduct for Liner Conferences 40 10. The Consultation System 46 * 11. Conference freight rates 49 12. Transport conditions 54 13. Marine insurance 56 V 14. -

Feasibility Analysis

Utah Inland Port - Feasibility Analysis prepared for World Trade Center - Utah Utah Governor's Office of Economic Development prepared by Cambridge Systematics, Inc Global Logistics Development Partners, Inc www.camsys.com report Utah Inland Port - Feasibility Analysis prepared for World Trade Center - Utah & Utah Governor's Office of Economic Development prepared by Cambridge Systematics, Inc. 115 South LaSalle Street, Suite 2200 Chicago, IL 60603 Global Logistics Development Partners 14362 N. Frank Lloyd Wright Blvd. Suite 1000 Scottsdale, AZ 85260 USA date December 29, 2017 Utah Inland Port - Feasibility Analysis Table of Contents Executive Summary ..................................................................................................... 2-7 Summary of Recommendations: .............................................................. 2-8 1.0 Introduction ....................................................................................................... 2-14 2.0 Inland Port Typology ....................................................................................... 2-17 2.1 What is an Inland Port?............................................................................ 2-17 2.2 Where are Existing Inland Ports? ........................................................... 2-17 Inland Port Types ..................................................................................... 2-17 Port Profile: DuisburgPort ....................................................................... 2-19 Port Profile: CentrePort Canada -

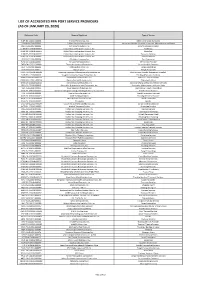

List of Accredited Ppa Port Service Providers (As of January 20, 2020)

LIST OF ACCREDITED PPA PORT SERVICE PROVIDERS (AS OF JANUARY 20, 2020) Reference Code Name of Applicant Type of Service RJDP-OS-112021-000001 R.J. Del Pan and Co., Inc. Marine and Cargo Surveyors SSSI-VR-112018-000003 SubSea Services Incoroprated Vessel and Marine Structure Inspection, Maintenance abd Repair RSSI-OS-112018-000004 RVV Security System, Inc. Security Services Provider GLMS-BU-112018-000005 Global Maritime Logistics Support, Inc. Bunkering GLMS-CD-112018-000005 Global Maritime Logistics Support, Inc. Chandling GLMS-TS-112018-000005 Global Maritime Logistics Support, Inc. Transport Services GLMS-OS-112018-000005 Global Maritime Logistics Support, Inc. Shipping Agency JBCI-OS-112018-000006 JRBuilders Company Inc. Port Contractor FEFC-OS-112018-000007 Far East Fuel Corporation SRF Service Provider TASS-CH-112021-000009 Taurus Arrastre and Stevedoring Cargo Handling Operator DLPI-TS-112018-000010 DRP Logistics Phils., Inc. Cargo Forwarding AJLS-TS-112018-000011 Alljoy Logistics Freight Forwarder OPME-OS-112018-000012 Optimum Equipment Management & Exchange Inc. Port Services Provider (Equipment Supplier) SCCF-TS-112018-000013 Straight Commercial Cargo Forwarders, Inc. Trucking (Transport Services) ONRS-TO-112021-000014 Omnico Natural Resources, Inc. Towing / Tugging Services ONRS-WS-112021-000014 Omnico Natural Resources, Inc. Watering Services ONRS-OS-112021-000014 Omnico Natural Resources, Inc. Cargo Surveying and Cargo Checking Services SRCI-OS-122018-000015 Super-Aire Refrigeration and Contractors, Inc. Preventive Maintenance of Air-con Units YLPI-TS-122018-000016 Yusen Logistics Philippines, Inc. International Freight Forwarding SCHS-PT-122018-000017 Samarenos Integrated Cargo Handling Services, Incorporated Port Terminal Services FCSI-TS-122018-000018 Fivestar Cargo Services, Inc. -

Port Regulation Overseeing the Economic Public Interest In

PORT REFORM TOOLKIT SECOND EDITION MODULE 6 PORT REGULATION MODULE THE WORLD BANK © 2007 The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank All rights reserved. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Public-Private Infrastructure Advisory Facility (PPIAF) or the Board of Executive Directors of the World Bank or the governments they represent. Neither PPIAF nor the World Bank guarantees the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of PPIAF or the World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. The material in this work is copyrighted. Copyright is held by the World Bank on behalf of both the World Bank and PPIAF. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including copying, recording, or inclusion in any information storage and retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the World Bank. MODULE 6 The World Bank encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission promptly. For all other queries on rights and licenses, including subsidiary rights, please contact the Office of the Publisher, World Bank, 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA, fax 202-522-2422, e-mail [email protected]. ISBN-10: 0-8213-6607-6 ISBN-13: 978-0-8213-6607-3 eISBN: 0-8213-6608-4 eISBN-13: 978-0-8213-6608-0 DOI: 10.1596/978-0-8213-6607-3 MODULE SIX CONTENTS 1. -

Caribbean Port Services Industry: Towards the Efficiency Frontier Caribbean Development Bank

TRANSFORMING THE CARIBBEAN PORT SERVICES INDUSTRY: TOWARDS THE EFFICIENCY FRONTIER CARIBBEAN DEVELOPMENT BANK TRANSFORMING THE CARIBBEAN PORT SERVICES INDUSTRY: TOWARDS THE EFFICIENCY FRONTIER ISBN 978-976-95695-8-4 Published by the Caribbean Development Bank CONTENT 08 09 Foreword Executive Summary 17 19 1. Introduction 2. Port Efficiency and Bottlenecks 1.1 General introduction 17 2.1 Introduction to the Issue of 19 1.2 Objectives of the Study 17 Port Efficiency 1.3 Scope of the Study 18 2.2 Overview of Port Characteristics 21 1.4 Report Structure 18 2.3 Port Efficiency Score 33 2.4 Main Bottlenecks in Efficiency 41 2.5 Enhancing Port Efficiency 47 50 66 3. Container Trade Patterns 4. Port Development Options and Forecasts 4.1 Development Vision 66 3.1 Introduction to Container Transport 50 4.2 Development Options 68 in the Caribbean Basin 3.2 Overview of Container Ports in the Caribbean Region 52 3.3 Maritime Connectivity Ports 54 3.4 Future Development of Container Transport in the Caribbean 56 3.5 Traffic Forecast for the BMC Ports 63 74 81 5. Conclusions & Recommendations 6. Annex I – Port Fact Sheets 5.1 Conclusions 74 Port Factsheet – Antigua, St. John’s 82 5.2 Recommendations 79 Port Factsheet – Bahamas, Nassau 86 Port Factsheet – Barbados, Bridgetown 90 Port Factsheet – Belize, Belize Port 94 Port Factsheet – Dominica, Rosseau 98 Port Factsheet – Grenada, St. George’s 101 Port Factsheet – Guyana, Georgetown 106 Port Factsheet – Saint Kitts and Nevis, Basseterre 110 Port Factsheet – Saint Lucia, Castries 113 Port Factsheet – Saint Vincent and The Grenadines, Kingtown 117 Port Factsheet – Suriname, Paramaribo 121 Port Factsheet – Trinidad and Tobago, Port of Spain 125 130 Annex II – Sources Used List of Boxes 1. -

U.S. Container Ports and Air Pollution: a Perfect Storm

Classic Columns Cover Stock U.S. Container Ports and Air Pollution: A Perfect Storm An Energy Futures, Inc. Study By James S. Cannon a U.S. Container Ports and Air Pollution: A Perfect Storm An Energy Futures, Inc. Study By James S. Cannon © 2008: Energy Futures, Inc. i Table of Contents Executive Summary 1 Chapter 1: Introduction 6 Chapter 2: Fndings and Recommendations 11 Chapter 3: Emissions from Port Operations 25 Chapter 4: Profiles of the 10 Largest U.S. Container Ports 36 Profile: Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach 37 Profile: Port of New York and New Jersey 46 Profile: Port of Oakland 50 Profile: Port of Savannah 55 Profile: Port of Tacoma 58 Profile: Port of Hampton Roads 61 Profile: Port of Seattle 64 Profile: Port of Charleston 70 Profile: Port of Houston 73 Acknowledgements 77 About the Author 77 References 79 iii iv Executive Summary Oceangoing container ships make more than 10,000 visits to ports in the United States (U.S.) from around the world each year. Delivery of goods to ports and from there to U.S. consumers is powered by diesel fuel each step of the way. Diesel fuel quality ranges from notoriously filthy bunker fuel that powers ships, to lower quality grades for offroad vehicles, to lower sulfur grades recently required for onroad trucks. Burning diesel fuel releases health threatening toxic air contaminants, smog forming air pollut- ants, and climate changing greenhouse gases. Air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions from international shipping are bad and getting worse. The combination of growing port activity, the densely populated regions where most ports are lo- cated, and the prevailing onshore wind patterns that accumulate, rather than disperse, port air pollution creates a “perfect storm” of threats to public health. -

A Stakeholder Perspective of Port City Sustainable Development

sustainability Article A Stakeholder Perspective of Port City Sustainable Development Jasmine Siu Lee Lam 1 and Wei Yim Yap 2,* 1 Maritime Energy and Sustainable Development Centre of Excellence, School of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore 639798, Singapore; [email protected] 2 School of Business, Singapore University of Social Sciences, Singapore 599494, Singapore * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +65-6248-4473 Received: 12 October 2018; Accepted: 7 January 2019; Published: 16 January 2019 Abstract: As world seaborne trade continues to grow, especially in view of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), there is a mounting demand for a sustainable balance among the economic, social, and environmental performance of the port cities involved. This study aims to first conduct a review of existing sustainability frameworks; second, conduct a stakeholder analysis for port city sustainable development. The case studies of two major port cities in China—Guangzhou and Shenzhen, are conducted. According to the findings, a structured framework with main categories of economic, social and environmental indicators would be recommended for port cities. Dealing with diversified stakeholders and their interests is a major challenge for policy makers to overcome but opportunities do co-exist. Policy makers of Guangzhou and Shenzhen have made progress in balancing economic, social, and environmental interests in recent years. This study has taken a step forward in the research area, with a view to provide reference to stakeholders and governments in progressing towards sustainable development in port cities. Keywords: port city; sustainable development; sustainability framework; stakeholder; Belt and Road Initiative 1. Introduction In response to rising pressures from growing world population, increasing resource consumption, environmental degradation and climate change, there is a clear call for sustainable development in the world today in order to meet the United Nations’ (UN) Millennium Development Goals. -

Competitiveness of South Asia's Container Ports

Competitiveness of South Asia’s Container Ports Container of South Asia’s Competitiveness DIRECTIONS IN DEVELOPMENT Infrastructure Herrera Dappe and Suárez-Alemán Herrera Competitiveness of South Asia’s Container Ports A Comprehensive Assessment of Performance, Drivers, and Costs Matías Herrera Dappe and Ancor Suárez-Alemán Competitiveness of South Asia’s Container Ports DIRECTIONS IN DEVELOPMENT Infrastructure Competitiveness of South Asia’s Container Ports A Comprehensive Assessment of Performance, Drivers, and Costs Matías Herrera Dappe and Ancor Suárez-Alemán © 2016 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000; Internet: www.worldbank.org Some rights reserved 1 2 3 4 19 18 17 16 This work is a product of the staff of The World Bank with external contributions. The findings, interpreta- tions, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Nothing herein shall constitute or be considered to be a limitation upon or waiver of the privileges and immunities of The World Bank, all of which are specifically reserved. Rights and Permissions This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO) http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo. -

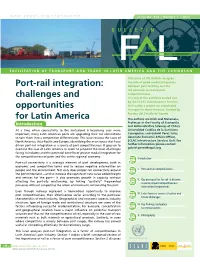

Port-Rail Integration: Between Port Facilities and the Rail Network to Ensure Port Competitiveness

www.cepal.org/transporte Issue No. 310 - Number 7 / 2012 BULLETIN FACILITATION OF TRANSPORT AND TRADE IN LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN This issue of FAL Bulletin analyses the role of good modal integration Port-rail integration: between port facilities and the rail network to ensure port competitiveness. challenges and It is one of the activities carried out by the ECLAC Infrastructure Services Unit under a project on sustainable opportunities transport in Ibero-America, funded by Puertos del Estado de España. for Latin America The authors are Erick Leal Matamala, Introduction Professor at the Faculty of Economics and Administrative Sciences of Chile’s At a time when connectivity to the hinterland is becoming ever more Universidad Católica de la Santísima important, many Latin American ports are upgrading their rail connections Concepción, and Gabriel Pérez Salas, to turn them into a competitive differentiator. This issue reviews the cases of Associate Economic Affairs Officer, North America, Asia-Pacific and Europe, identifying the main issues that have ECLAC Infrastructure Services Unit. For driven port-rail integration as a source of port competitiveness. It goes on to further information please contact: examine the case of Latin America in order to pinpoint the main challenges [email protected] facing its industry and the potential benefits of greater modal integration for the competitiveness of ports and the entire regional economy. Introduction Port-rail connectivity is a strategic element of port development, both in economic and competitive terms and to reduce negative externalities on people and the environment. Not only does proper rail connectivity expand I.