Paradoxes in Jīva Gosvāmī's Concept of the Soul, Path to Perfection And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Understanding the Super Excellence of Gaudiya Vaishnavism

Understanding the Super Excellence of Gaudiya Vaishnavism Understanding the Super Excellence of Gaudiya Vaishnavism. So that is the theme, understanding the super excellence of Gaudiya Vaishnavism. Srila Prabhupada ki jay! He was and he is Gaudiya Vaishnava, coming in the line of disciplic succession and we are getting connected. So we are making this presentation, I won’t say this is complete presentation but some introductory presentation to make the point that Gaudiya Vaishnavism is super excellent like, mattah parataram nanyat kincid asti dhananjaya mayi sarvam idam protam sutre mani-gana iva [Bg 7.7] Translation: O conqueror of wealth [Arjuna], there is no Truth superior to Me. Everything rests upon Me, as pearls are strung on a thread. Krishna said no one is equal to me and no one is superior to me. So Krishna is super excellent personality of godhead. So like that there are different features of Gaudiya Vaishnavism, so we have picked up a few items which are listed here. Achintya-Bheda-Abheda tattva or philosophy or the commentary on vedanta sutra is of Gaudiya Vaishnavas is super excellent, so that one. And Gaudiya sampradaya is super excellent and raganuga sadhana bhakti. And Goloka dhama, amongst all the dhamas and there are many of them, is the topmost realm, super excellent and that is Gaudiya Vaishnavas preference, they don’t settle on any other level they go all the way to the top, topmost abode, super excellent abode Goloka. Mellows of bhakti, Gaudiya Vaishnavas only settle for the topmost rasa, madhurya rasa. That is what Sri Krishna Chaitanya Mahaprabhu relished and shared. -

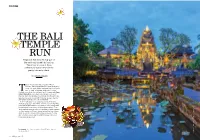

THE BALI TEMPLE RUN Temples in Bali Share the Top Spot on the Must-Visit List with Its Beaches

CULTURE THE BALI TEMPLE RUN Temples in Bali share the top spot on the must-visit list with its beaches. Take a look at some of these architectural marvels that dot the pretty Indonesian island. TEXT ANURAG MALLICK he sun was about to set across the cliffs of Uluwatu, the stony headland that gave the place its name. Our guide, Made, explained that ulu is ‘land’s end’ or ‘head’ in Balinese, while watu is ‘stone’. PerchedT on a rock at the southwest tip of the peninsula, Pura Luhur Uluwatu is a pura segara (sea temple) and one of the nine directional temples of Bali protecting the island. We gaped at the waves crashing 230 ft below, unaware that the real spectacle was about to unfold elsewhere. A short walk led us to an amphitheatre overlooking the dramatic seascape. In the middle, around a sacred lamp, fifty bare-chested performers sat in concentric rings, unperturbed by the hushed conversations of the packed audience. They sat in meditative repose, with cool sandalwood paste smeared on their temples and flowers tucked behind their ears. Sharp at six, chants of cak ke-cak stirred the evening air. For the next one hour, we sat open-mouthed in awe at Bali’s most fascinating temple ritual. Facing page: Pura Taman Saraswati is a beautiful water temple in the heart of Ubud. Elena Ermakova / Shutterstock.com; All illustrations: Shutterstock.com All illustrations: / Shutterstock.com; Elena Ermakova 102 JetWings April 2017 JetWings April 2017 103 CULTURE The Kecak dance, filmed in movies such as There are four main types of temples in Bali – public Samsara and Tarsem Singh’s The Fall, was an temples, village temples, family temples for ancestor worship, animated retelling of the popular Hindu epic and functional temples based on profession. -

Brahma Sutra

BRAHMA SUTRA CHAPTER 1 1st Pada 1st Adikaranam to 11th Adhikaranam Sutra 1 to 31 INDEX S. No. Topic Pages Topic No Sutra No Summary 5 Introduction of Brahma Sutra 6 1 Jijnasa adhikaranam 1 a) Sutra 1 103 1 1 2 Janmady adhikaranam 2 a) Sutra 2 132 2 2 3 Sastrayonitv adhikaranam 3 a) Sutra 3 133 3 3 4 Samanvay adhikaranam 4 a) Sutra 4 204 4 4 5 Ikshatyadyadhikaranam: (Sutras 5-11) 5 a) Sutra 5 324 5 5 b) Sutra 6 353 5 6 c) Sutra 7 357 5 7 d) Sutra 8 362 5 8 e) Sutra 9 369 5 9 f) Sutra 10 372 5 10 g) Sutra 11 376 5 11 2 S. No. Topic Pages Topic No Sutra No 6 Anandamayadhikaranam: (Sutras 12-19) 6 a) Sutra 12 382 6 12 b) Sutra 13 394 6 13 c) Sutra 14 397 6 14 d) Sutra 15 407 6 15 e) Sutra 16 411 6 16 f) Sutra 17 414 6 17 g) Sutra 18 416 6 18 h) Sutra 19 425 6 19 7 Antaradhikaranam: (Sutras 20-21) 7 a) Sutra 20 436 7 20 b) Sutra 21 448 7 21 8 Akasadhikaranam : 8 a) Sutra 22 460 8 22 9 Pranadhikaranam : 9 a) Sutra 23 472 9 23 3 S. No. Topic Pages Topic No Sutra No 10 Jyotischaranadhikaranam : (Sutras 24-27) 10 a) Sutra 24 486 10 24 b) Sutra 25 508 10 25 c) Sutra 26 513 10 26 d) Sutra 27 517 10 27 11 Pratardanadhikaranam: (Sutras 28-31) 11 a) Sutra 28 526 11 28 b) Sutra 29 538 11 29 c) Sutra 30 546 11 30 d) Sutra 31 558 11 31 4 SUMMARY Brahma Sutra Bhasyam Topics - 191 Chapter – 1 Chapter – 2 Chapter – 3 Chapter – 4 Samanvaya – Avirodha – non – Sadhana – spiritual reconciliation through Phala – result contradiction practice proper interpretation Topics - 39 Topics - 47 Topics - 67 Topics 38 Sections Topics Sections Topics Sections Topics Sections Topics 1 11 1 13 1 06 1 14 2 07 2 08 2 08 2 11 3 13 3 17 3 36 3 06 4 08 4 09 4 17 4 07 5 Lecture – 01 Puja: • Gratitude to lord for completion of Upanishad course (last Chandogya Upanishad + Brihadaranyaka Upanishad). -

Brahman, Atman and Maya

Sanatana Dharma The Eternal Way of Life (Hinduism) Brahman, Atman and Maya The Hindu Way of Comprehending Reality and Life Brahman, Atman and Maya u These three terms are essential in understanding the Hindu view of reality. v Brahman—that which gives rise to maya v Atman—what each maya truly is v Maya—appearances of Brahman (all the phenomena in the cosmos) Early Vedic Deities u The Aryan people worship many deities through sacrificial rituals: v Agni—the god of fire v Indra—the god of thunder, a warrior god v Varuna—the god of cosmic order (rita) v Surya—the sun god v Ushas—the goddess of dawn v Rudra—the storm god v Yama—the first mortal to die and become the ruler of the afterworld The Meaning of Sacrificial Rituals u Why worship deities? u During the period of Upanishads, Hindus began to search for the deeper meaning of sacrificial rituals. u Hindus came to realize that presenting offerings to deities and asking favors in return are self-serving. u The focus gradually shifted to the offerings (the sacrificed). u The sacrificed symbolizes forgoing one’s well-being for the sake of the well- being of others. This understanding became the foundation of Hindu spirituality. In the old rites, the patron had passed the burden of death on to others. By accepting his invitation to the sacrificial banquet, the guests had to take responsibility for the death of the animal victim. In the new rite, the sacrificer made himself accountable for the death of the beast. -

Panchadashee – 05 Mahavakya Vivekah

Swami Vidyaranya’s PANCHADASHEE – 05 MAHAVAKYA VIVEKAH Fixing the Meaning of the Great Sayings MODERN-DAY REFLECTIONS On a 13TH CENTURY VEDANTA CLASSIC by a South African Student TEXT Swami Gurubhaktananda 47.05 2018 A FOUNDATIONAL TEXT ON VEDANTA PHILOSOPHY PANCHADASHEE – An Anthology of 15 Texts by Swami Vidyaranyaji PART Chap TITLE OF TEXT ENGLISH TITLE No. No. Vers. 1 Tattwa Viveka Differentiation of the Supreme Reality 65 2 Maha Bhoota Viveka Differentiation of the Five Great Elements 109 3 Pancha Kosha Viveka Differentiation of the Five Sheaths 43 SAT: 4 Dvaita Viveka Differentiation of Duality in Creation 69 VIVEKA 5 Mahavakya Viveka Fixing the Meaning of the Great Sayings 8 Sub-Total A 294 6 Chitra Deepa The Picture Lamp 290 7 Tripti Deepa The Lamp of Perfect Satisfaction 298 8 Kootastha Deepa The Unchanging Lamp 76 CHIT: DEEPA 9 Dhyana Deepa The Lamp of Meditation 158 10 Nataka Deepa The Theatre Lamp 26 Sub-Total B 848 11 Yogananda The Bliss of Yoga 134 12 Atmananda The Bliss of the Self 90 13 Advaitananda The Bliss of Non-Duality 105 14 Vidyananda The Bliss of Knowledge 65 ANANDA: 15 Vishayananda The Bliss of Objects 35 Sub-Total C 429 WHOLE BOOK 1571 AN ACKNOWLEDGEMENT BY THE STUDENT/AUTHOR The Author wishes to acknowledge the “Home Study Course” offerred by the Chinmaya International Foundation (CIF) to students of Vedanta in any part of the world via an online Webinar service. These “Reflections” are based on material he has studied under this Course. CIF is an institute for Samskrit and Indology research, established in 1990 by Pujya Gurudev, Sri Swami Chinmayananda, with a vision of it being “a bridge between the past and the present, East and West, science and spirituality, and pundit and public.” CIF is located at the maternal home and hallowed birthplace of Adi Shankara, the great saint, philosopher and indefatigable champion of Advaita Vedanta, at Veliyanad, 35km north-east of Ernakulam, Kerala, India. -

Meningkatkan Mutu Umat Melalui Pemahaman Yang Benar Terhadap Simbol Acintya (Perspektif Siwa Siddhanta)

MENINGKATKAN MUTU UMAT MELALUI PEMAHAMAN YANG BENAR TERHADAP SIMBOL ACINTYA (PERSPEKTIF SIWA SIDDHANTA) Oleh: I Gusti Made Widya Sena Dosen Fakultas Brahma Widya IHDN Denpasar Abstract God will be very difficult if understood with eye, to the knowledge of God through nature, private and personification through the use of various symbols God can help humans understand God's infinite towards the unification of these two elements, namely the unification of physical and spiritual. Acintya as a symbol or a manifestation of God 's Omnipotence itself . That what really " can not imagine it turns out " could imagine " through media portrayals , relief or statue. All these symbols are manifested Acintya it by taking the form of the dance of Shiva Nataraja, namely as a depiction of God's omnipotence , to bring in the actual symbol " unthinkable " that have a meaning that people are in a situation where emotions religinya very close with God. Keywords: Theology, Acintya, Siwa Siddhanta & Siwa Nataraja I. PENDAHULUAN Kehidupan sebagai manusia merupakan hidup yang paling sempurna dibandingkan dengan makhluk ciptaan Tuhan lainnya, hal ini dikarenakan selain memiliki tubuh jasmani, manusia juga memiliki unsur rohani. Kedua unsur ini tidak dapat dipisahkan dan saling melengkapi diantara satu dengan lainnya. Layaknya garam di lautan, tidak dapat dilihat secara langsung tapi terasa asin ketika dikecap. Jasmani manusia difungsikan ketika melakukan berbagai macam aktivitas di dunia, baik dalam memenuhi kebutuhan hidup (kebutuhan pangan, sandang dan papan), reproduksi, bersosialisasi dengan makhluk lainnya, dan berbagai aktivitas lainnya, sedangkan tubuh rohani difungsikan dalam merasakan, memahami dan membangun hubungan dengan Sang Pencipta, sehingga ketenangan, keindahan dan kebijaksanaan lahir ketika penyatuan diantara kedua unsur ini berjalan selaras, serasi dan seimbang. -

Notes on Hinduism

NOTES ON HINDUISM Note: Many "Hindus" prefer the name "Sanatana Dharma" (Eternal Truth) for their religion. "Hinduism" – meaning "the religions of the Indians" – is a term that was probably introduced by the British in the 18th century. BASIC BELIEFS The origins of Hinduism have been dated as early as 3000 BC. It is a rich religious and cultural tradition containing and encompassing many diverse and even conflicting beliefs and practices. While there is, in Hinduism, no rigidly enforced set of doctrines or dogmas, there is a configuration of themes and claims that represents a generally agreed upon Hindu belief system. 1. Hindus believe in a single Supreme Reality known as Brahman, which is the ultimate source of the cosmos and all things in it. Some Hindus consider Brahman to be God, a savior to be loved and worshiped; others think of it as a Transcendent and Unmanifest Absolute, a Ground of Being, without any of the characteristics traditionally attributed to "God" by religious believers. The three main characteristics of Brahman are sat (absolute being), chit (absolute consciousness and knowledge), and ananda (absolute bliss). The Supreme Reality in its transcendent, absolute, and unmanifest essence is called Nirguna-Brahman (unrevealed, "without attributes"); in its revealed or manifest nature, it is called Saguna-Brahman ("with attributes"). There are three major manifestations of Saguna-Brahman: Brahma (God the Creator), Vishnu (God the Preserver) and Shiva (God the Destroyer). Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva (the Trimurti, the "three forms" of Brahman) are not really three distinct deities in addition to the supreme Brahman; rather, they are the three ways in which Brahman is manifested in the cosmos and in which Brahman appears to human consciousness. -

What the Upanisads Teach

What the Upanisads Teach by Suhotra Swami Part One The Muktikopanisad lists the names of 108 Upanisads (see Cd Adi 7. 108p). Of these, Srila Prabhupada states that 11 are considered to be the topmost: Isa, Kena, Katha, Prasna, Mundaka, Mandukya, Taittiriya, Aitareya, Chandogya, Brhadaranyaka and Svetasvatara . For the first 10 of these 11, Sankaracarya and Madhvacarya wrote commentaries. Besides these commentaries, in their bhasyas on Vedanta-sutra they have cited passages from Svetasvatara Upanisad , as well as Subala, Kausitaki and Mahanarayana Upanisads. Ramanujacarya commented on the important passages of 9 of the first 10 Upanisads. Because the first 10 received special attention from the 3 great bhasyakaras , they are called Dasopanisad . Along with the 11 listed as topmost by Srila Prabhupada, 3 which Sankara and Madhva quoted in their sutra-bhasyas -- Subala, Kausitaki and Mahanarayana Upanisads --are considered more important than the remaining 97 Upanisads. That is because these 14 Upanisads are directly referred to by Srila Vyasadeva himself in Vedanta-sutra . Thus the 14 Upanisads of Vedanta are: Isa, Kena, Katha, Prasna, Mundaka, Mandukya, Aitareya, Taittiriya, Brhadaranyaka, Chandogya, Svetasvatara, Kausitaki, Subala and Mahanarayana. These 14 belong to various portions of the 4 Vedas-- Rg, Yajus, Sama and Atharva. Of the 14, 8 ( Brhadaranyaka, Chandogya, Taittrirya, Mundaka, Katha, Aitareya, Prasna and Svetasvatara ) are employed by Vyasa in sutras that are considered especially important. In the Gaudiya Vaisnava sampradaya , Srila Baladeva Vidyabhusana shines as an acarya of vedanta-darsana. Other great Gaudiya acaryas were not met with the need to demonstrate the link between Mahaprabhu's siksa and the Upanisads and Vedanta-sutra. -

The Essence of the Samkhya II Megumu Honda

The Essence of the Samkhya II Megumu Honda (THE THIRD CHAPTER) (The opponent questions;) Now what are the primordial Matter and others, from which the soul should be discriminated? (The author) replies; They are the primordial Matter (prakrti), the Intellect (buddhi), the Ego- tizing organ (ahankara), the subtle Elements (tanmatra), the eleven sense organs (indriya) and the gross Elements (bhuta) in sum just 24." The quality (guna), the action (karman) and the generality (samanya) are included in them because a property and one who has property are iden- tical (dharma-dharmy-abhedena). Here to be the primordial Matter means di- rectly (or) indirectly to be the material cause (upadanatva) of all the mo- dification (vikara), because its chief work (prakrsta krtih) is formed of tra- nsf ormation (parinama), -thus is the etymology (of prakrti). The primordial Matter (prakrti), the Capacity (sakti), the Unborn (aja), the Principal (pra- dhana), the Unevolved (avyakta), the Dark (tamers), the Illusion (maya), the Ignorance (avidya) and so on are the synonyms') of the primordial Matter. For the traditional scripture says; "Brahmi (the Speech) means the science (vidya) and the Ignorace (avidya) means illusion (maya) -said the other. (It is) the primordial Matter and the Highest told the great sages2)." And here the satt va and other three substances are implied (upalaksita) as. the state of equipoise (samyavastha)3). (The mention is) limitted to implication 1) brahma avyakta bahudhatmakam mayeti paryayah (Math. ad SK. 22), prakrtih pradhanam brahma avyaktam bahudhanakammayeti paryayah (Gaudap. ad SK. 22), 自 性 者 或 名 勝 因 或 名 爲 梵 或 名 衆 持(金 七 十 論ad. -

Samkhya System

HE RITA G E O F INDIA . ZARIAH The Right Reverend V S A , Bishop of Dornakal . AR UHAR . ITT . J N F " , M A , D L Alr a u lish d e dy p b e . Th f B u h e e a r K . M A. H o dd s m . S AU S . t i I NDER , R As ok . D M . M P M . M . a E V . A A HA L . J C I , , In a di n a n n . r n a Y B c l OW Ca lcu ta . P i ti g P i ip PERC R N , t Ka n r r r RE . E B . ese e a u . R a L e V . A it t P ICE , n s u n r aration S u bjects p roposed a d volu me de p rep . A KRIT A D R R S N S N P ALI LITE AT U E . M O ord H mns r h V d A . A . A LL O . r . y f om t e e a s . P o f CD NE , xf n h r . ro . LA A t olo gy o f M a hayana Lite ra tu e P f . L DE VALLEE ou e Gh e n . P s , t M A h S e le c r h h ST R . D m n a d . W e l . ons o t e U a s s . ti f p i F J E E N , i M M . -

Shraman Bhagavan Mahavira and Jainism the Jaina

SHRAMAN BHAGAVAN MAHAVIRAAND JAINISM By: Dr. Ramanlal C. Shah Published - Jain Society of Metro Washington Shraman Bhagavan Mahavira and Jainism JAINISM Jainism is one of the greatest and the oldest religions of the world, though it is not known much outside India. Even in India, compared to the total population of India, Jainism at present is followed by a minority of the Indian population amounting to about four million people. Yet Jainism is not unknown to the scholars of the world in the field of religion and philosophy, because of its highest noble religious principles. Though followed by relatively less people in the world, Jainism is highly respected by all those non-Jainas who have studied Jainism or who have come into contact with the true followers of Jainism. There are instances of non- Jaina people in the world who have most willingly either adopted Jainism or have accepted and put into practice the principles of Jainism. Though a religion of a small minority, Jainism is not the religion of a particular race, caste or community. People from all the four classified communities of ancient India; Brahmin, Kshatriya, Vaishya, and Shudra have followed Jainism. In the principles of Jainism, there is nothing which would debar a person of any particular nation, race, caste, community, creed, etc., from following Jainism. Hence Jainism is a Universal Religion. The followers of Jainism are called Jainas. The word "Jaina" is derived from the Sanskrit word "Jina." One who follows and worships Jina is called a Jaina. Etymologically "Jina" means the conqueror or the victorious. -

Jiva Or Soul in Jainism Dr. N.L.Kachhara Jiva Or Soul the Jaina Conception of Jiva (Soul) Occupies the First Place Among the Doctrines of Independent Soul

Jiva or Soul in Jainism Dr. N.L.Kachhara Jiva or Soul The Jaina conception of Jiva (Soul) occupies the first place among the doctrines of independent soul. The Jaina view of soul appears to be older than the views of other Indian systems of thought and it is comprehensible to the common people. This sentient principle was well established as the object of meditation for liberation of Lord Parshvanath in the eighth century B.C. The Jaina doctrine of soul did not change from the long past to the present time as it happened in the Buddhist and Vedic traditions The term Jiva connotes that Soul is consciousness itself and consciousness also is invariably soul. The Jiva is non-corporeal, living, eternal and permanent, and fixed (constant) substance of the Cosmic Universe, having the attributes of consciousness (Cetana). Jiva is the generic name of sentient substance. Jiva substance is non-physical and is not sense - perceptible; it does not have the properties of colour, smell, taste and touch. Consciousness and upayoga are the differentia of the jiva. Upayoga and consciousness are the two sides of the same entity jiva. Consciousness may be interpreted both as a structure and a function of the jiva but upayoga refers to the functional side only. Upayoga gives us almost the same meaning as we get by being mentally active. Just as a mental activity is a fact of mental functioning and a mental capacity, a fact of mental structure; in the same way consciousness or chetana may be taken as a fact of the jiva’s structure and upayoga, as a fact of the jiva’s function.