Volume 55, Number 1 01/01/2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Venomous Snakes in Pennsylvania the First Question Most People Ask When They See a Snake Is “Is That Snake Poisonous?” Technically, No Snake Is Poisonous

Venomous Snakes in Pennsylvania The first question most people ask when they see a snake is “Is that snake poisonous?” Technically, no snake is poisonous. A plant or animal that is poisonous is toxic when eaten or absorbed through the skin. A snake’s venom is injected, so snakes are classified as venomous or nonvenomous. In Pennsylvania, we have only three species of venomous snakes. They all belong to the pit viper Nostril family. A snake that is a pit viper has a deep pit on each side of its head that it uses to detect the warmth of nearby prey. This helps the snake locate food, especially when hunting in the darkness of night. These Pit pits can be seen between the eyes and nostrils. In Pennsylvania, Pennsylvania Snakes all of our venomous Checklist snakes have slit-like A complete list of Pennsylvania’s pupils that are 21 species of snakes. similar to a cat’s eye. Venomous Nonvenomous Copperhead (venomous) Nonvenomous snakes Eastern Garter Snake have round pupils, like a human eye. Eastern Hognose Snake Eastern Massasauga (venomous) Venomous If you find a shedded snake Eastern Milk Snake skin, look at the scales on the Eastern Rat Snake underside. If they are in a single Eastern Ribbon Snake Eastern Smooth Earth Snake row all the way to the tip of its Eastern Worm Snake tail, it came from a venomous snake. Kirtland’s Snake If the scales split into a double row Mountain Earth Snake at the tail, the shedded skin is from a Northern Black Racer Nonvenomous nonvenomous snake. -

The Herpetology of Erie County, Pennsylvania: a Bibliography

The Herpetology of Erie County, Pennsylvania: A Bibliography Revised 2 nd Edition Brian S. Gray and Mark Lethaby Special Publication of the Natural History Museum at the Tom Ridge Environmental Center, Number 1 2 Special Publication of the Natural History Museum at the Tom Ridge Environmental Center The Herpetology of Erie County, Pennsylvania: A Bibliography Revised 2 nd Edition Compiled by Brian S. Gray [email protected] and Mark Lethaby Natural History Museum at the Tom Ridge Environmental Center, 301 Peninsula Dr., Suite 3, Erie, PA 16505 [email protected] Number 1 Erie, Pennsylvania 2017 Cover image: Smooth Greensnake, Opheodrys vernalis from Erie County, Pennsylvania. 3 Introduction Since the first edition of The herpetology of Erie County, Pennsylvania: a bibliography (Gray and Lethaby 2012), numerous articles and books have been published that are pertinent to the literature of the region’s amphibians and reptiles. The purpose of this revision is to provide a comprehensive and updated list of publications for use by researchers interested in Erie County’s herpetofauna. We have made every effort to include all major works on the herpetology of Erie County. Included are the works of Atkinson (1901) and Surface (1906; 1908; 1913) which are among the earliest to note amphibians and or reptiles specifically from sites in Erie County, Pennsylvania. The earliest publication to utilize an Erie County specimen, however, may have been that of LeSueur (1817) in his description of Graptemys geographica (Lindeman 2009). While the bibliography is quite extensive, we did not attempt to list everything, such as articles in local newspapers, and unpublished reports, although some of the more significant of these are included. -

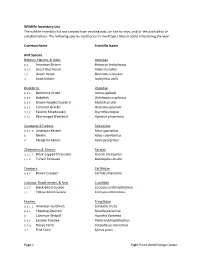

Master Wildlife Inventory List

Wildlife Inventory List The wildlife inventory list was created from existing data, on site surveys, and/or the availability of suitable habitat. The following species could occur in the Project Area at some time during the year: Common Name Scientific Name Bird Species Bitterns, Herons, & Allies Ardeidae D, E American Bittern Botaurus lentiginosus A, E, F Great Blue Heron Ardea herodias E, F Green Heron Butorides virescens D Least bittern Ixobrychus exilis Blackbirds Icteridae B, E, F Baltimore Oriole Icterus galbula B, E, F Bobolink Dolichonyx oryzivorus B, E, F Brown-headed Cowbird Molothrus ater B, E, F Common Grackle Quiscalus quiscula B, E, F Eastern Meadowlark Sturnella magna B, E, F Red-winged Blackbird Agelaius phoeniceus Caracaras & Falcons Falconidae B, E, F, G American Kestrel Falco sparverius B Merlin Falco columbarius D Peregrine Falcon Falco peregrinus Chickadees & Titmice Paridae B, E, F, G Black-capped Chickadee Poecile atricapillus E, F, G Tufted Titmouse Baeolophus bicolor Creepers Certhiidae B, E, F Brown Creeper Certhia americana Cuckoos, Roadrunners, & Anis Cuculidae D, E, F Black-billed Cuckoo Coccyzus erythropthalmus E, F Yellow-billed Cuckoo Coccyzus americanus Finches Fringillidae B, E, F, G American Goldfinch Carduelis tristis B, E, F Chipping Sparrow Spizella passerina G Common Redpoll Acanthis flammea B, E, F Eastern Towhee Pipilo erythrophthalmus E, F, G House Finch Carpodacus mexicanus B, E Pine Siskin Spinus pinus Page 1 Eight Point Wind Energy Center E, F, G Purple Finch Carpodacus purpureus B, E Red Crossbill -

Standard Common and Current Scientific Names for North American Amphibians, Turtles, Reptiles & Crocodilians

STANDARD COMMON AND CURRENT SCIENTIFIC NAMES FOR NORTH AMERICAN AMPHIBIANS, TURTLES, REPTILES & CROCODILIANS Sixth Edition Joseph T. Collins TraVis W. TAGGart The Center for North American Herpetology THE CEN T ER FOR NOR T H AMERI ca N HERPE T OLOGY www.cnah.org Joseph T. Collins, Director The Center for North American Herpetology 1502 Medinah Circle Lawrence, Kansas 66047 (785) 393-4757 Single copies of this publication are available gratis from The Center for North American Herpetology, 1502 Medinah Circle, Lawrence, Kansas 66047 USA; within the United States and Canada, please send a self-addressed 7x10-inch manila envelope with sufficient U.S. first class postage affixed for four ounces. Individuals outside the United States and Canada should contact CNAH via email before requesting a copy. A list of previous editions of this title is printed on the inside back cover. THE CEN T ER FOR NOR T H AMERI ca N HERPE T OLOGY BO A RD OF DIRE ct ORS Joseph T. Collins Suzanne L. Collins Kansas Biological Survey The Center for The University of Kansas North American Herpetology 2021 Constant Avenue 1502 Medinah Circle Lawrence, Kansas 66047 Lawrence, Kansas 66047 Kelly J. Irwin James L. Knight Arkansas Game & Fish South Carolina Commission State Museum 915 East Sevier Street P. O. Box 100107 Benton, Arkansas 72015 Columbia, South Carolina 29202 Walter E. Meshaka, Jr. Robert Powell Section of Zoology Department of Biology State Museum of Pennsylvania Avila University 300 North Street 11901 Wornall Road Harrisburg, Pennsylvania 17120 Kansas City, Missouri 64145 Travis W. Taggart Sternberg Museum of Natural History Fort Hays State University 3000 Sternberg Drive Hays, Kansas 67601 Front cover images of an Eastern Collared Lizard (Crotaphytus collaris) and Cajun Chorus Frog (Pseudacris fouquettei) by Suzanne L. -

Preliminary Morphometrics, Growth, and Natural History Observations Of

RESEARCH ARTICLE The Herpetological Bulletin 141, 2017: 1-6 Preliminary morphometrics, growth, and natural history observations of the short-headed garter snake, Thamnophis brachystoma at two urban sites in Erie County, Pennsylvania, USA BRIAN S. GRAY* & MARK LETHABY Natural History Museum at the Tom Ridge Environmental Center 301 Peninsula Drive, Erie, Pennsylvania 16505, USA *Corresponding author Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT - We used mark-recapture techniques to study the short-headed garter snake, Thamnophis brachystoma at two urban sites (Shannon Road and McClelland Park) in Erie County, Pennsylvania, USA. Mean snout-vent length (SVL) and weight was greater in females than males regardless of age class; whereas relative to total length, tail length was consistently greater in males than in females. Sex ratios did not differ significantly from 1:1 regardless of age-class. At Shannon Road, adults significantly outnumbered juveniles 3.3 to 1. While at McClelland Park, juveniles (N = 63) were nearly twice as numerous as adults (N = 31). Data regarding estimated growth are also reported. The results of the present study conform to previously published data from populations in Pennsylvania and a population near Olean, New York. INTRODUCTION he short-headed garter snake, Thamnophis brachystoma (Fig. 1) is relatively small with a recorded maximum Tlength of 578 mm (Lethaby, 2004). It is found primarily in early successional habitats in the Allegheny High Plateau of north-western Pennsylvania and south-western New York, USA (Price, 1978). Introduced populations have been reported in New York (Bothner, 1976), Ohio (Novotny, 1990; Novotny et al., 2011), and Pennsylvania (Price, 1978; McCoy, 1982). -

Supporting Information

Convergent Evolution of Toxin Resistance SUPPORTING INFORMATION Title: Widespread convergence in toxin resistance by predictable molecular evolution Authors: Beata Ujvari, Nicholas R. Casewell, Kartik Sunagar, Kevin Arbuckle, Wolfgang Wüster, Nathan Lo, Denis O’Meally, Christa Beckmann, Glenn F. King, Evelyne Deplazes and Thomas Madsen Abstract: The question about whether evolution is unpredictable and stochastic or intermittently constrained along predictable pathways is the subject of a fundamental debate in biology, in which understanding convergent evolution plays a central role. At the molecular level, documented examples of convergence are rare and limited to occurring within specific taxonomic groups. Here we provide evidence of constrained convergent molecular evolution across the metazoan tree of life. We show that resistance to toxic cardiac glycosides produced by plants and bufonid toads is mediated by similar molecular changes to the sodium-potassium-pump (Na+/K+- ATPase) in insects, amphibians, reptiles and mammals. In toad-feeding reptiles, resistance is conferred by two point mutations that have evolved convergently on four occasions, whilst evidence of a molecular reversal back to the susceptible state in varanid lizards migrating to toad-free areas suggests that toxin resistance is maladaptive in the absence of selection. Importantly, resistance in all taxa is mediated by replacements of two of the 12 amino acids comprising the Na+/K+-ATPase H1-H2 extracellular domain that constitutes a core part of the cardiac glycoside binding site. We provide mechanistic insight into the basis of resistance by showing that these alterations perturb the interaction between the cardiac glycoside bufalin and the Na+/K+-ATPase. Thus, similar selection pressures have resulted in convergent evolution of the same molecular solution across the breadth of the animal kingdom, demonstrating how a scarcity of possible solutions to a selective challenge can lead to highly predictable evolutionary responses. -

Wildlife Site Characterization Report South Ripley Solar Town of Ripley Chautauqua County, New York

Wildlife Site Characterization Report South Ripley Solar Town of Ripley Chautauqua County, New York Prepared for: ConnectGen LLC 1001 McKinney, Suite 700 Houston, Texas 77002 Prepared by: Environmental Design & Research, Landscape Architecture, Engineering, & Environmental Services, D.P.C. 217 Montgomery Street, Suite 1000 Syracuse, New York 13202 www.edrdpc.com February 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................... 1 2.0 PUBLICLY AVAILABLE DATA SOURCES ........................................................................................................ 2 2.1 NEW YORK’S EAF MAPPER ....................................................................................................................... 2 2.2 NEW YORK’S ENVIRONMENTAL RESOURCE MAPPER .......................................................................... 2 2.3 NEW YORK NATURAL HERITAGE PROGRAM.......................................................................................... 3 2.4 USFWS IPaC and ECOS DATABASES ....................................................................................................... 3 2.5 NEW YORK’S NATURE EXPLORER ........................................................................................................... 4 2.6 NEW YORK’S BIODIVERSITY AND WIND SITING MAPPING TOOL......................................................... 4 2.7 CORNELL LABORATORY OF ORNITHOLOGY’s eBird ............................................................................. -

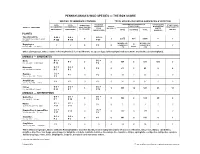

2010 Box Score

PENNSYLVANIA’S WILD SPECIES — THE BOX SCORE SPECIES* OF IMMEDIATE CONCERN TOTAL SPECIES (INCLUDING SUBSPECIES & VARIETIES) PRESUMED REPRODUCING CURRENTLY IN NON-BREEDING PABS- PABS- DOWNLISTED PENNSYLVANIA EXTIRPATED EXTINCT PENNSYLVANIA MIGRANTS OR GROUP OF ORGANISMS RECOMMENDED RECOMMENDED SINCE 1990 DUE RESPONSIBILITY FROM (GLOBALLY) WINTER † † TO RECOVERY ‡ ENDANGERED THREATENED PENNSYLVANIA NATIVE NONNATIVE TOTAL RESIDENTS SPECIES PLANTS Vascular plants G 24 + G 4 + G 10 + Rev. May 2010 — B. Isaac, S. Grund 0 2 2,075 931 3,006 — ? & T. Block P 300 P 115 P 97 MOSSES ~350 0 MOSSES ~350 Bryophytes ? ? 0 P 3 0 LIVERWORTS LIVERWORTS — ? Rev. Sep. 2007 — J. Lendemer ~150 known ~150 Other plant groups, whose status in Pennsylvania is less well known, are green algae (Chlorophyta) and stoneworts or pondweeds (Charophyta). ANIMALS — CHORDATES G 1 + G 2 + Birds P 3 2 2 184 5 189 196 9 Rev. June 2010 — M. Brittingham P 14 P 4 G 1 + G 2 + Mammals 1 P 9 0 63 3 65 0 4 Rev. June 2010 — M. Gannon P 3 P 1 G 2 + Reptiles P 1 0 P 2 0 35 1 36 0 7 To be rev. Aug. 2010 — T. Maret P 2 Amphibians P 4 P 1 0 P 1 0 37 0 37 0 3 To be rev. Aug. 2010 — T. Maret G 5 + G 2 + G 2 + Fishes 6 1 165 18 183 26 13 Rev. June 2010 — R. Criswell P 23 P 7 P 14 ANIMALS — ARTHROPODS G 4 + G 1 + G 1 + Butterflies 0 0 122 2 124 20 2 Rev. July 2010 — B. -

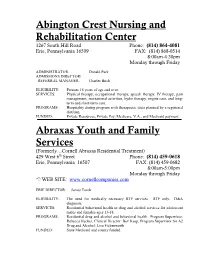

Human-Services-Directory.Pdf

Abington Crest Nursing and Rehabilitation Center 1267 South Hill Road Phone: (814) 864-4081 Erie, Pennsylvania 16509 FAX: (814) 868-0514 8:00am-4:30pm Monday through Friday ADMINISTRATOR: Donald Park ADMISSIONS DIRECTOR/ REFERRAL MANAGER: Charles Bush ELIGIBILITY: Persons 16 years of age and over. SERVICES: Physical therapy, occupational therapy, speech therapy, IV therapy, pain management, recreational activities, hydro therapy, respite care, and long- term and short-term care. PROGRAMS: Hospitality dining program with therapeutic diets planned by a registered dietitian. FUNDED: Private Resources, Private Pay, Medicare, V.A., and Medicaid payment. Abraxas Youth and Family Services (Formerly…Cornell Abraxas Residential Treatment) 429 West 6th Street Phone: (814) 459-0618 Erie, Pennsylvania 16507 FAX: (814) 459-0682 8:00am-5:00pm Monday through Friday WEB SITE: www.cornellcompanies.com ERIE DIRECTOR: James Torok ELIGIBILITY: The need for medically necessary RTF services. RTF only. D&A diagnosis. SERVICES: Residential behavioral health or drug and alcohol services for adolescent males and females ages 13-18. PROGRAMS: Residential drug and alcohol and behavioral health. Program Supervisor: Rebecca Hecker, Clinical Director: Bev Keep, Program Supervisor for A2 Drug and Alcohol: Lisa Fickenworth FUNDED: State Medicaid and county funded. Achievement Center, Inc. 101 East 6th Street Phone: (814) 459-2755 Erie, Pennsylvania 16507 or toll free (888) 321-3110 FAX: (814) 456-4873 8:00am-5:00pm EMAIL: [email protected] Monday through Friday WEB PAGE: www.achievementctr.org BOARD PRESIDENT: Michael Butler EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR: Rebecca N. Brumagin ELIGIBILITY: Children ages birth through 21 years of age with physical disability, developmental delays, or mental health / behavioral issues. -

A Guide to the Reptiles of Erie County, Pennsylvania

2 A Guide to the Reptiles of Erie County, Pennsylvania BRIAN S. GRAY Natural History Museum at the Tom Ridge Environmental Center Erie, Pennsylvania, USA. Published by Brian S. Gray Copyright © 2011 Brian S. Gray 3 Table of Contents Introduction…6 Acknowledgements…9 Species accounts…10 Snakes Harmless egg-laying snakes Eastern Racer…12 Milk Snake…14 Smooth Green Snake…16 Midland Rat Snake…18 Slender rear-fanged snakes (harmless) Ringneck Snake…20 Harmless live-bearing snakes Northern Water Snake…22 Queen Snake…24 Brown Snake…26 Redbelly Snake…28 Shorthead Garter Snake…30 Eastern Ribbon Snake…32 Common Garter Snake…34 Robust rear-fanged snakes (harmless) Eastern Hognose Snake…36 Lizards Skinks Five-lined Skink…40 4 Turtles Snapping turtles Common Snapping Turtle…44 Mud and Musk Turtles Common Musk Turtle…48 Box and Basking Turtles Spotted Turtle…50 Northern Painted Turtle…52 Blanding’s Turtle…54 Wood Turtle…56 Common Map Turtle…58 Eastern Box Turtle…60 Softshells Spiny Softshell…62 Nonnative species…64 Identifying shed snakeskins…66 Glossary…75 Maps…78 Bibliography…82 5 INTRODUCTION Erie County in northwestern Pennsylvania, a formerly glaciated region, is unique among the commonwealth’s 67counties in that it is bordered by Lake Erie on its north side. The county is divided into 21 townships (Figure 1) and contains the city of Erie, the fourth largest city in Pennsylvania. Two physiographic provinces occur in the county, the Central Lowland and the Appalachian Plateaus. The Central Lowland province consists of a narrow band 2–5 miles wide extending along the Lake Erie shoreline. -

ITC Lake Erie Connector Environmental Report

Lake Erie Connector Project Environmental Report May 2015 Prepared for: ITC Lake Erie Connector LLC Novi, Michigan Prepared by: HDR Engineering, Inc. Portland, Maine May 2015 LAKE ERIE CONNECTOR PROJECT ENVIRONMENTAL REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Title Page No. 1.0 Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 1-1 1.1 Purpose and Need ................................................................................................ 1-2 1.1.1 Project Purpose ........................................................................................ 1-2 1.1.2 Project Need ............................................................................................. 1-2 1.1.2.1 Power System Reliability Benefits.......................................... 1-2 1.1.2.2 Market Efficiency Benefits ..................................................... 1-3 1.1.2.3 Environmental Benefits ........................................................... 1-3 2.0 Project Description ........................................................................................................... 2-1 2.1 General Project Description ................................................................................. 2-1 2.2 Erie Converter Station Description ...................................................................... 2-3 2.2.1 General Facility Location and Description, Erie Converter Station ........ 2-3 2.2.2 Construction Methods, Erie Converter Station ....................................... -

Shipboard Curriculum Guide Lake Erie Science

Shipboard Curriculum Guide Lake Erie Science A Guide for Preparing, Producing and Extending an Understanding of Great Lakes Science through Experiential Learning for Middle through High School Students Experiencing, Investigating, Learning LAKE ERIE SCIENCE FIELD STUDIES Pennsylvania TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................... 1 PRE-FIELD EXPERIENCE ............................................................................. 5 Lesson Plan .......................................................................................... 6 Teacher resource information ................................................................ 8 The Great Lakes.................................................................................... 8 Presque Isle Bay ................................................................................... 8 Research Vessel Environaut ................................................................... 9 FIELD EXPERIENCE ................................................................................... 13 Orientation ......................................................................................... 14 Site Sampling Map .............................................................................. 15 Biological Science ................................................................................ 16 Physical Science .................................................................................. 20 Chemical Science ...............................................................................................