Skou Tonal System (Mark Donohue)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mian Grammar

A Grammar of Mian, a Papuan Language of New Guinea Olcher Sebastian Fedden Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2007 Department of Linguistics and Applied Linguistics The University of Melbourne Produced on archival quality paper 2 To my parents 3 Abstract This thesis is a descriptive grammar of the Mian language of Papua New Guinea. The corpus data on the basis of which I analyzed the structures of the language and their functions was obtained during nine months of field work in Yapsiei and Mianmin, Telefomin District, Sandaun Province, Papua New Guinea. The areas of grammar I cover in this thesis are phonology (ch. 2), word classes (ch. 3), nominal classification (ch. 4 and 5), noun phrase structure (ch. 6), verb morphology (ch. 7), argument structure and syntax of the clause (ch. 8), serial verb constructions and clause chaining (ch. 9), operator scope (ch. 10), and embedding (ch. 11). Mian has a relatively small segmental phoneme inventory. The tonal phonology is complex. Mian is a word tone language, i.e. the domain for assignment of one of five tonemes is the phonological word and not the syllable. There is hardly any nominal morphology. If a noun is used referentially, it is followed by a cliticized article. Mian has four genders. Agreement targets are the article, determiners, such as demonstratives, and the pronominal affixes on the verb. The structure of the NP is relatively simple and constituent order is fixed. The rightmost position in the NP is reserved for a determiner; e.g. -

Major Families of the Worlds Languages As Linguistic Areas

MAJOR FAMILIES OF THE WORLDS LANGUAGES AS LINGUISTIC AREAS LECTURE NOTE PREPARED BY MR. IFEDIORA OKICHE [email protected] Department of Languages and Linguistics Arthur Jarvis University Akpabuyo, Cross River State, Nigeria PRESENTATION PREPARED BY JACOB ONYEBUCHI [email protected] 2017/2018 Batch B Stream 2 Corps Member Arthur Jarvis University Akpabuyo, Cross River State, Nigeria NIGER – CONGO AS A LINGUISTIC AREA • Adamawa – Ubangi * • Efik * • Yoruba * 2 ADAMAWA – UBANGI The language grouped together as Adamawa – Ubangi belongs to the Volta-Congo branch of the Niger-Congo family. These languages are speakers across central Africa in an area that stretches from north-eastern Nigeria through northern Cameroon, southern Chad, the Central African Republic, and northern Zaire. The languages fall into two groups – Adamawa and Ubangi. The Adamawa languages are found in northern Nigeria, Cameroon and Chad, whereas the Ubangi languages are spoken in Central African Republic, northern Zaire and southwestern Sudan. 3 EFIK Efik is one of the better known African languages and was at one time one of the best described African languages. It is spoken today by about 750,000 people as a first language in the south south corner of Nigeria, in and around the city of Calabar, its cultural center. Due to its location near the Atlantic coast, Calabar and the Efik were encountered early by European explorers, traders and missionaries. Efik is now recognized as part of lower Cross, a subgroup of Cross River which is a branch of the Niger-Congo linguistic Area. 4 YORUBA Yoruba is spoken as a first language in Nigeria in virtually all areas in the states of Ekiti, Lagos, Ogun, Ondo, Osun and Oyo and in most of the areas in Kwara and Kogi State. -

Computing a World Tree of Languages from Word Lists

From words to features to trees: Computing a world tree of languages from word lists Gerhard Jäger Tübingen University Heidelberg Institute for Theoretical Studies October 16, 2017 Gerhard Jäger (Tübingen) Words to trees HITS 1 / 45 Introduction Introduction Gerhard Jäger (Tübingen) Words to trees HITS 2 / 45 Introduction Language change and evolution The formation of dierent languages and of distinct species, and the proofs that both have been developed through a gradual process, are curiously parallel. [...] We nd in distinct languages striking homologies due to community of descent, and analogies due to a similar process of formation. The manner in which certain letters or sounds change when others change is very like correlated growth. [...] The frequent presence of rudiments, both in languages and in species, is still more remarkable. [...] Languages, like organic beings, can be classed in groups under groups; and they can be classed either naturally according to descent, or articially by other characters. Dominant languages and dialects spread widely, and lead to the gradual extinction of other tongues. (Darwin, The Descent of Man) Gerhard Jäger (Tübingen) Words to trees HITS 3 / 45 Introduction Language change and evolution Vater Unser im Himmel, geheiligt werde Dein Name Onze Vader in de Hemel, laat Uw Naam geheiligd worden Our Father in heaven, hallowed be your name Fader Vor, du som er i himlene! Helliget vorde dit navn Gerhard Jäger (Tübingen) Words to trees HITS 4 / 45 Introduction Language change and evolution Gerhard Jäger -

Mark Donohue

Mark Donohue Address: Department of Linguistics, 12 Nelson Place School of Culture, History and Language, Curtin College of Asia and the Pacific, ACT 2605 Coombs Building, Australia Australian National University, ACT 0200, Australia Tel: 0418 644 933 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.donohue.cc or http://papuan.linguistics.anu.edu.au/Donohue/ or http://asiapacific.anu.edu.au/people/personal/donom_ling.php or https://researchers.anu.edu.au/researchers/donohue-mh Nationality: Australian / British (dual nationality) Languages: Native: English Good: Tukang Besi, Indonesian, Eastern Indonesian non-standard Malay(s), Tok Pisin Intermediate: Dutch, Palu’e, Skou, Japanese, Nepali Basic: One, Mandarin, Cantonese, Iha, Kuke, Kusunda, Bumthang. Academic Positions Language Intelligence, October 2016 ongoing Partner Partner in a consulting firm providing expert advice and applied research in the fields of language, including but not limited to Forensic linguistics, Database assembly, and Typological consulting. Australian National University, June 2015 ongoing Senior Research Fellow, Department of Linguistics, School of Culture, History and Language Continuing research into the linguistic histories in Asia and the Pacific; exploring quantitative methods in comparative linguistics; phonological and tonological analysis. (approximately equal to Associate Research Professor) Australian National University, June 2011 – May 2015 Future Fellow, Department of Linguistics, School of Culture, History and Language (ARC-funded research position) Research into the linguistic macrohistory of Asia and the Pacific; exploring quantitative methods in comparative linguistics; developing testable theories of language contact and language change. Australian National University, January 2011 ongoing Senior Research Fellow, Department of Linguistics, School of Culture, History and Language Continuing research into the linguistic macrohistory of Asia and the Pacific; exploring quantitative methods in comparative linguistics. -

The World Tree of Languages: How to Infer It from Data, and What It Is Good For

The world tree of languages: How to infer it from data, and what it is good for Gerhard Jäger Tübingen University Workshop Evolutionary Theory in the Humanities, Torun April 14, 2018 Gerhard Jäger (Tübingen) Words to trees Torun 1 / 42 Introduction Introduction Gerhard Jäger (Tübingen) Words to trees Torun 2 / 42 Introduction Language change and evolution “If we possessed a perfect pedigree of mankind, a genealogical arrangement of the races of man would afford the best classification of the various languages now spoken throughout the world; and if all extinct languages, and all intermediate and slowly changing dialects, had to be included, such an arrangement would, I think, be the only possible one. Yet it might be that some very ancient language had altered little, and had given rise to few new languages, whilst others (owing to the spreading and subsequent isolation and states of civilisation of the several races, descended from a common race) had altered much, and had given rise to many new languages and dialects. The various degrees of difference in the languages from the same stock, would have to be expressed by groups subordinate to groups; but the proper or even only possible arrangement would still be genealogical; and this would be strictly natural, as it would connect together all languages, extinct and modern, by the closest affinities, and would give the filiation and origin of each tongue.” (Darwin, The Origin of Species) Gerhard Jäger (Tübingen) Words to trees Torun 3 / 42 Introduction Language phylogeny Comparative method 1 -

LCSH Section T

T (Computer program language) T cell growth factor T-Mobile G1 (Smartphone) [QA76.73.T] USE Interleukin-2 USE G1 (Smartphone) BT Programming languages (Electronic T-cell leukemia, Adult T-Mobile Park (Seattle, Wash.) computers) USE Adult T-cell leukemia UF Safe, The (Seattle, Wash.) T (The letter) T-cell leukemia virus I, Human Safeco Field (Seattle, Wash.) [Former BT Alphabet USE HTLV-I (Virus) heading] T-1 (Reading locomotive) (Not Subd Geog) T-cell leukemia virus II, Human Safeco Park (Seattle, Wash.) BT Locomotives USE HTLV-II (Virus) The Safe (Seattle, Wash.) T.1 (Torpedo bomber) T-cell leukemia viruses, Human BT Stadiums—Washington (State) USE Sopwith T.1 (Torpedo bomber) USE HTLV (Viruses) t-norms T-6 (Training plane) (Not Subd Geog) T-cell receptor genes USE Triangular norms UF AT-6 (Training plane) BT Genes T One Hundred truck Harvard (Training plane) T cell receptors USE Toyota T100 truck T-6 (Training planes) [Former heading] USE T cells—Receptors T. rex Texan (Training plane) T-cell-replacing factor USE Tyrannosaurus rex BT North American airplanes (Military aircraft) USE Interleukin-5 T-RFLP analysis Training planes T cells USE Terminal restriction fragment length T-6 (Training planes) [QR185.8.T2] polymorphism analysis USE T-6 (Training plane) UF T lymphocytes T. S. Hubbert (Fictitious character) T-18 (Tank) Thymus-dependent cells USE Hubbert, T. S. (Fictitious character) USE MS-1 (Tank) Thymus-dependent lymphocytes T. S. W. Sheridan (Fictitious character) T-18 light tank Thymus-derived cells USE Sheridan, T. S. W. (Fictitious -

Languages of Indonesia (Papua)

Ethnologue report for Indonesia (Papua) Page 1 of 49 Languages of Indonesia (Papua) See language map. Indonesia (Papua). 2,220,934 (2000 census). Information mainly from C. Roesler 1972; C. L. Voorhoeve 1975; M. Donohue 1998–1999; SIL 1975–2003. The number of languages listed for Indonesia (Papua) is 271. Of those, 269 are living languages and 2 are second language without mother-tongue speakers. Living languages Abinomn [bsa] 300 (1999 Clouse and Donohue). Lakes Plain area, from the mouth of the Baso River just east of Dabra at the Idenburg River to its headwaters in the Foya Mountains, Jayapura Kabupaten, Mamberamo Hulu Kecamatan. Alternate names: Avinomen, "Baso", Foya, Foja. Dialects: Close to Warembori. Classification: Language Isolate More information. Abun [kgr] 3,000 (1995 SIL). North coast and interior of central Bird's Head, north and south of Tamberau ranges. Sorong Kabupaten, Ayamaru, Sausapor, and Moraid kecamatans. About 20 villages. Alternate names: Yimbun, A Nden, Manif, Karon. Dialects: Abun Tat (Karon Pantai), Abun Ji (Madik), Abun Je. Classification: West Papuan, Bird's Head, North-Central Bird's Head, North Bird's Head More information. Aghu [ahh] 3,000 (1987 SIL). South coast area along the Digul River west of the Mandobo language, Merauke Kabupaten, Jair Kecamatan. Alternate names: Djair, Dyair. Classification: Trans-New Guinea, Main Section, Central and Western, Central and South New Guinea-Kutubuan, Central and South New Guinea, Awyu-Dumut, Awyu, Aghu More information. Airoran [air] 1,000 (1998 SIL). North coast area on the lower Apauwer River. Subu, Motobiak, Isirania and other villages, Jayapura Kabupaten, Mamberamo Hilir, and Pantai Barat kecamatans. -

SEALS XIV Volume 1 Papers from the 14Th Annual Meeting of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society 2004 Edited by Wilaiwan Khanittanan and Paul Sidwell

Pacific Linguistics Electronic Publication E-5 SEALS XIV Volume 1 Papers from the 14th annual meeting of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society 2004 edited by Wilaiwan Khanittanan and Paul Sidwell Pacific Linguistics Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies The Australian National University Pacific Linguistics E-5 Pacific Linguistics is a publisher specialising in grammars and linguistic descriptions, dictionaries and other materials on languages of the Pacific, Taiwan, the Philippines, Indonesia, East Timor, southeast and south Asia, and Australia. Pacific Linguistics, established in 1963 through an initial grant from the Hunter Douglas Fund, is associated with the Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies at The Australian National University. The authors and editors of Pacific Linguistics publications are drawn from a wide range of institutions around the world. Publications are refereed by scholars with relevant expertise, who are usually not members of the editorial board. FOUNDING EDITOR: Stephen A. Wurm EDITORIAL BOARD: John Bowden, Malcolm Ross and Darrell Tryon (Managing Editors), I Wayan Arka, David Nash, Andrew Pawley, Paul Sidwell, Jane Simpson EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD: Karen Adams, Arizona State University Lillian Huang, National Taiwan Normal Alexander Adelaar, University of Melbourne University Peter Austin, School of Oriental and African Bambang Kaswanti Purwo, Universitas Atma Studies Jaya Byron Bender, University of Hawai‘i Marian Klamer, Universiteit Leiden Walter Bisang, Johannes Gutenberg- Harold Koch, The -

Languages of the World

CONCISE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF LANGUAGES OF THE WORLD COORDINATING EDITOR KEITH BROWN University of Cambridge Cambridge, UK CO-EDITOR SARAH OGILVIE University of Oxford Oxford, UK Amsterdam Boston Heidelberg London New York Oxford Paris San Diego San Francisco Singapore Sydney Tokyo SUBJECT CLASSIFICATION Note that italicized titles are included for classification purposes only and do not cross-refer to articles. Introduction Eastern List of Abbreviations Akkadian Classification of Languages Southern Ethiopian Semitic Languages Areal Linguistics Amharic Africa as a Linguistic Area Ga'sz Balkans as a Linguistic Area Tigrinya Ethiopia as a Linguistic Area Europe as a Linguistic Area Altaic Languages South Asia as a Linguistic Area Southeast Asia as a Linguistic Area Mongolic Languages Tungusic Languages Evenki Afroasiatic Languages Turkic Languages Ancient Egyptian and Coptic Azerbaijanian Berber Languages Bashkir Chadic Languages Chuvash Hausa Kazakh Cushitic Languages Kirghiz Highland East Cushitic Languages Tatar Oromo Turkish Somali Turkmen Omotic Languages Uyghur Wolaitta Uzbek Semitic Languages Yakut Eblaite Central Arabic Australian Languages Arabic Languages, Varation in Australia: Language Situation Aramaic and Syriac Mirndi Hebrew, Biblical and Jewish Wambaya Hebrew, Israeli Pama-Nyungan Jewish languages Arrernte Maltese Gamilaraay Phoenician Guugu Yimithirr Syriac Jiwarli Ugaritic Kalkutungu xii Subject Classification Kaytetye Caucasian Languages Morrobalama Abkhaz Pitjantjatjara / Yankunytjatjara Georgian Warlpiri Lak Southern Daly -

ANUARIO DEL SEMINARIO DE FILOLOGÍA VASCA «JULIO DE URQUIJO» International Journal of Basque Linguistics and Philology

ANUARIO DEL SEMINARIO DE FILOLOGÍA VASCA «JULIO DE URQUIJO» International Journal of Basque Linguistics and Philology LII: 1-2 (2018) Studia Philologica et Diachronica in honorem Joakin Gorrotxategi Vasconica et Aquitanica Joseba A. Lakarra - Blanca Urgell (arg. / eds.) AASJUSJU 22018018 Gorrotxategi.indbGorrotxategi.indb i 331/10/181/10/18 111:06:151:06:15 How Many Language Families are there in the World? Lyle Campbell University of Hawai‘i Mānoa DOI: https://doi.org/10.1387/asju.20195 Abstract The question of how many language families there are in the world is addressed here. The reasons for why it has been so difficult to answer this question are explored. The ans- wer arrived at here is 406 independent language families (including language isolates); however, this number is relative, and factors that prevent us from arriving at a definitive number for the world’s language families are discussed. A full list of the generally accepted language families is presented, which eliminates from consideration unclassified (unclas- sifiable) languages, pidgin and creole languages, sign languages, languages of undeciphe- red writing systems, among other things. A number of theoretical and methodological is- sues fundamental to historical linguistics are discussed that have impacted interpretations both of how language families are established and of particular languages families, both of which have implications for the ultimate number of language families. Keywords: language family, family tree, unclassified language, uncontacted groups, lan- guage isolate, undeciphered script, language surrogate. 1. Introduction How many language families are there in the world? Surprisingly, most linguists do not know. Estimates range from one (according to supporters of Proto-World) to as many as about 500. -

Skou Language Analysis

A most agreeable language* MARK DONOHUE University of Sydney [email protected] 1. Agreement and the notions of economy and redundancy In this paper I shall present data on multiple exponence from Skou, a language of New Guinea, and show that it presents problems for most accounts of inflectional morphology, because of the essentially unpredictable number of ways in which the same agreement features are realised on a given lexical item. Following a sketch of the historical situation that lies behind the Skou agreement system, similarities in Bantu nominal inflection are drawn and an argument is made for a templatic model of inflection that resides in the lexicon, dictating morphological choices. Different theories of morphology and syntax treat the mechanism of agreement in different ways, both from each other and for different patterns of agreement (see, eg., Bresnan and Mchombo 1987, Andrews 1990, Jelinek and Demers 1994, Stump 2001, and many others, some of which are referred to later in this paper). Furthermore, most modern morphosyntactic theories avow some principle of economy, although the way in which such a principle is modelled varies between frameworks. What they do share is the basic assumption that languages employ the most economical set of morphemes needed to realise the meaning and grammatical features required. For instance, describing the way in which the Economy Principle works in the Minimalist Program (MP), Radford (1997: 505) states that it is: A principle which requires that (all other things being equal)1 syntactic representations should contain as few constituents and syntactic derivations involve as few grammatical operations as possible. -

Skou Summary Notes, Part 1 (Mark Donohue)

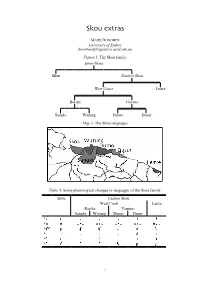

MARK DONOHUE University of Sydney [email protected] Figure 1. The Skou family proto-Skou Skou Eastern Skou West Coast Leitre Border Vanimo Sangke Wutung Dumo Dusur Map 3. The Skou languages Table 4. Some phonological changes in languages of the Skou family Skou Eastern Skou West Coast Leitre Border Vanimo Sangke Wutung Dumo Dusur * * * * * * 1 2 Figure 2. The Macro-Skou family Macro-Skou linkage Skou-Serra-Piore linkage Krisa Skou Serra Hills Piore River (see fig. 1) Pu Rawo-Main Serra Warapu Rw Main Serra chain So Rm Ba Su Wm Mo No Ross (1980) presented a sketch of the Dumo language, which represents in many ways a subset of the grammatical patterns found in Skou. From a Dumo perspective, the salient differences between it and Skou involve the lack of consonant clusters in Skou, the differences in segmental phonologies, and the case marking system in Skou. The elaborations of multiple agreement found in Skou are not a feature of Dumo, nor is the gender system. Table 10. Skou and Dumo compared Skou Dumo Comments 1. Stops Dumo lacks palatal or velar stops; Skou lacks alveolar voicing 2. Fricatives Skou lacks an s; Dumo lacks the glottal fricative1 3. Sonorants Skou has added r 4. Syllable pitches high, low, fall high, low, fall identical, with identical tone sandhi (though see 2.xx.xx) 5. Lexical clusters none Skou lacks clusters 6. Case ergative, instrumental none Dumo lacks case 7. Agreement clitic, prefix, vowel prefix, (vowel) Skou has more elaborate agreement 8. Classification 2 genders and 2 2 classes Skou shows a more elaborate classes system 9.