The Classification of Sicilian Dialects: Language Change and Contact Silvio Cruschina (University of Helsinki)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Provincia Regionale Di Caltanissetta Codice Fiscale E Partita IVA: 00115070856

N.P. 139 del 28/03/2011 Provincia Regionale di Caltanissetta Codice Fiscale e Partita IVA: 00115070856 SETTORE VII – VIABILITA’ E TRASPORTI DETERMINAZIONE DIRIGENZIALE N. 574 DEL 28/03/2011 OGGETTO : Autorizzazione per lo svolgimento della gara ciclistica categoria cicloamatori, denominata Gran Fondo e Medio Fondo del Vallone, gara di osservazione nazionale che si terrà a Caltanissetta il 10 aprile 2011, e che attraverserà i Comuni di Caltanissetta, San Cataldo, Serradifalco, Montedoro, Bompensiere, Milena, Acquaviva Platani, Mussomeli. IL DIRIGENTE PREMESSO : • che con istanza del 20/02/2011 assunta da questa Provincia Regionale il 24/02/2011 con prot. 2011/0005030, il Sig. Rosario Domenico Fina nella qualità di Presidente dell'Associazione Sportiva Dilettantistica “Eventi”, con sede in Serradifalco C/da Cusatino sn, ha chiesto il N.O. per l'uso di strade provinciali, per lo svolgimento di una gara ciclistica categoria cicloamatori, denominata Gran Fondo e Medio Fondo del Vallone, gara di osservazione Nazionale, competizione ciclistica specialità Strada riservata a tutte le categorie federali della F.C.I. e degli Enti di Promozione Sportiva, che si terrà a Caltanissetta il 10 aprile 2011dalle ore 9:00 alle ore 13:00 e che attraverserà i Comuni di Caltanissetta, San Cataldo, Serradifalco, Montedoro, Bompensiere, Milena, Acquaviva Platani, Mussomeli; • che con successiva nota dell'11/03/2011, assunta da questa Provincia Regionale il 14/03/2011 con prot. 2011/0006856, il Sig. Rosario Domenico Fina nella qualità di Presidente dell'Associazione -

“Calcare Di Base” Formations from Caltanissetta (Sicily) and Rossano (Calabria) Basins: a Detailed Geochemical, Sedimentological and Bio-Cyclostratigraphical Study

EGU2020-19511 https://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-egu2020-19511 EGU General Assembly 2020 © Author(s) 2021. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. New insights of Tripoli and “Calcare di Base” Formations from Caltanissetta (Sicily) and Rossano (Calabria) Basins: a detailed geochemical, sedimentological and bio-cyclostratigraphical study. Athina Tzevahirtzian1, Marie-Madeleine Blanc-Valleron2, Jean-Marie Rouchy2, and Antonio Caruso1 1Dipartimento di Scienze della Terra e del Mare (DiSTeM), Università degli Studi di Palermo, via Archirafi 20-22, 90123 Palermo, Italy 2CR2P, UMR 7207, Sorbonne Universités-MNHN, CNRS, UMPC-Paris 6, Muséum national d’histoire naturelle, 57 rue Cuvier, Paris, France A detailed biostratigraphical and cyclostratigraphical study provided the opportunity of cycle-by- cycle correlations between sections from the marginal and deep areas of the Caltanissetta Basin (Sicily), and the northern Calabrian Rossano Basin. All the sections were compared with the Falconara-Gibliscemi composite section. We present new mineralogical and geochemical data on the transition from Tripoli to Calcare di Base (CdB), based on the study of several field sections. The outcrops display good record of the paleoceanographical changes that affected the Mediterranean Sea during the transition from slightly restricted conditions to the onset of the Mediterranean Salinity Crisis (MSC). This approach permitted to better constrain depositional conditions and highlighted a new palaeogeographical pattern characterized -

Buccini the Merchants of Genoa and the Diffusion of Southern Italian Pasta Culture in Europe

Anthony Buccini The Merchants of Genoa and the Diffusion of Southern Italian Pasta Culture in Europe Pe-i boccoin boin se fan e questioin. Genoese proverb 1 Introduction In the past several decades it has become received opinion among food scholars that the Arabs played the central rôle in the diffusion of pasta as a common food in Europe and that this development forms part of their putative broad influence on culinary culture in the West during the Middle Ages. This Arab theory of the origins of pasta comes in two versions: the basic version asserts that, while fresh pasta was known in Italy independently of any Arab influence, the development of dried pasta made from durum wheat was a specifically Arab invention and that the main point of its diffusion was Muslim Sicily during the period of the island’s Arabo-Berber occupation which began in the 9th century and ended by stages with the Norman conquest and ‘Latinization’ of the island in the eleventh/twelfth century. The strong version of this theory, increasingly popular these days, goes further and, though conceding possible native European traditions, posits Arabic origins not only for dried pasta but also for the names and origins of virtually all forms of pasta attested in the Middle Ages, albeit without ever providing credible historical and linguistic evidence; Clifford Wright (1999: 618ff.) is the best known proponent of this approach. In AUTHOR 2013 I demonstrated that the commonly held belief that lasagne were an Arab contribution to Italy’s culinary arsenal is untenable and in particular that the Arabic etymology of the word itself, proposed by Rodinson and Vollenweider, is without merit: both word and item are clearly of Italian origin. -

Trapani Palermo Agrigento Caltanissetta Messina Enna

4 A Sicilian Journey 22 TRAPANI 54 PALERMO 86 AGRIGENTO 108 CALTANISSETTA 122 MESSINA 158 ENNA 186 CATANIA 224 RAGUSA 246 SIRACUSA 270 Directory 271 Index III PALERMO Panelle 62 Panelle Involtini di spaghettini 64 Spaghetti rolls Maltagliati con l'aggrassatu 68 Maltagliati with aggrassatu sauce Pasta cone le sarde 74 Pasta with sardines Cannoli 76 Cannoli A quarter of the Sicilian population reside in the Opposite page: province of Palermo, along the northwest coast of Palermo's diverse landscape comprises dramatic Sicily. The capital city is Palermo, with over 800,000 coastlines and craggy inhabitants, and other notable townships include mountains, both of which contribute to the abundant Monreale, Cefalù, and Bagheria. It is also home to the range of produce that can Parco Naturale delle Madonie, the regional natural be found in the area. park of the Madonie Mountains, with some of Sicily’s highest peaks. The park is the source of many wonderful food products, such as a cheese called the Madonie Provola, a unique bean called the fasola badda (badda bean), and manna, a natural sweetener that is extracted from ash trees. The diversity from the sea to the mountains and the culture of a unique city, Palermo, contribute to a synthesis of the products and the history, of sweet and savoury, of noble and peasant. The skyline of Palermo is outlined with memories of the Saracen presence. Even though the churches were converted by the conquering Normans, many of the Arab domes and arches remain. Beyond architecture, the table of today is still very much influenced by its early inhabitants. -

Nome(I) Ingrao Antonio

Curriculum Vitae Informazioni personali Cognome(i/)/Nome(i) Ingrao Antonio Indirizzo(i) Piazza Garibaldi n° 11 – 93010 Milena ( CL ) – Sicilia - Italia Telefono(i) +39 0934 933916 Mobile: +39 334 6243310 Fax + E-mail [email protected] oppure [email protected] Cittadinanza Italiana Data di nascita 06/03/1957 Sesso Maschile Occupazione Incarico dirigenziale desiderata/Settore professionale Esperienza professionale Date 21-02-2010 ad oggi Lavoro o posizione ricoperti Dirigente terza fascia – Ruolo Unico della Dirigenza – Vice presidente Commissione di Gara presso UREGA sezione provinciale di Siracusa Principali attività e Celebrazione gare d’appalto - Contenzioso . responsabilità Nome e indirizzo del datore di Regione Siciliana – Ass.to Reg.le delle Infrastrutture e della Mobilità - Dipartimento delle Infrastrutture, della lavoro Mobilità e dei Trasporti - UREGA sezione provinciale di Siracusa , via delle Carceri Vecchie n° 36 - Siracusa Tipo di attività o settore Ente pubblico Date 24-09-2001 al 20-02-2010 Lavoro o posizione ricoperti Dirigente terza fascia – Ruolo Unico della Dirigenza – UOBC 1- Segreteria tecnica dell’Ingegnere Capo Principali attività e Controllo di gestione - Pratiche di pertinenza dell’Ingegnere Capo - Verifica e monitoraggio attività dell’Ufficio con responsabilità riferimento agli obiettivi assegnati - Rapporti con le OO.SS. - Rapporti con l’utenza esterna ed interna - Adempimenti connessi alla Conferenza speciale dei servizi- Coordinamento attività dello Sportello Unico - Ufficio U.R.P. ( informazioni, -

Orari E Sedi Dei Centri Di Vaccinazione Dell'asp Di Caltanissetta

ELENCO CENTRI DI VACCINAZIONE ASP CALTANISSETTA Presidio Altro personale che Giorni e orario di ricevimento Recapito e-mail * Medici Infermieri Comune ( collabora al pubblico Cammarata Giuseppe Bellavia M. Rosa L-M -M -G-V h 8.30-12.30 Caltanissetta Via Cusmano 1 pad. C 0934 506136/137 [email protected] Petix Vincenza ar er Russo Sergio Scuderi Alfia L e G h 15.00-16.30 previo appuntamento L-Mar-Mer-G-V h 8.30-12.30 Milisenna Rosanna Modica Antonina Caltanissetta Via Cusmano 1 pad. B 0934 506135/009 [email protected] Diforti Maria L e G h 15.00 - 16.30 Giugno Sara Iurlaro Maria Antonia Sedute vaccinali per gli adolescenti organizzate previo appuntamento Delia Via S.Pertini 5 0922 826149 [email protected] Virone Mario Rinallo Gioacchino // Lunedì e Mercoledì h 9 -12.00 Sanfilippo Salvatore Sommatino Via A.Moro 76 0922 871833 [email protected] // // Lunedì e Venerdì h 9.00 -12.00 Castellano Paolina L e G ore p.m. previo appuntamento Resuttano Via Circonvallazione 4 0934 673464 [email protected] Accurso Vincenzo Gangi Maria Rita // Previo appuntamento S.Caterina Accurso Vincenzo Fasciano Rosamaria M V h 9.00-12.00 Via Risorgimento 2 0934 671555 [email protected] // ar - Villarmosa Severino Aldo Vincenti Maria L e G ore p.m. previo appuntamento Martedì e Giovedì h 9.00-12.00 Riesi C/da Cicione 0934 923207 [email protected] Drogo Fulvio Di Tavi Gaetano Costanza Giovanna L - G p.m. -

Riepilogo Periodo

Riepilogo periodo: 31/12/2020 - 29/04/2021 Giorni effettivi di vaccinazione Comune di Gagliano Castelferrato (EN) Prot. N.0004568 del 04-05-2021 arrivo Cat14 Cl.1 Fascicolo 113 / Periodo selezionato Centro vaccinale Riepilogo delle vaccinazioni effettuate 31/12/2020 29/04/2021 Tutte Somministrazioni e Totali per Data Vaccinazione e Tipo Vaccino Somministrazioni cumulate per data vaccinazione e proiezione a 10 gg Tipo Vaccino ASTRAZENECA MODERNA PFIZER Totali 70K 1.400 60K 1.200 ate 50K 1.000 ul um c oni i 40K oni az 800 i tr az s tr ni i s 30K m ni 600 i m om S om 20K 400 S 200 10K 0 0K gen 2021 feb 2021 mar 2021 apr 2021 gen 2021 feb 2021 mar 2021 apr 2021 mag 2021 Data Vaccinazione Data Vaccinazione Dosi somministrate % per Vaccino Dosi 1 2 Dose 1 2 Totale Vaccino Somministra % Somministra % Somministra % 3,6K (6,7%) 9,02K zioni zioni zioni (16,79%) ASTRAZENECA 8999 16,76% 17 0,03% 9016 16,79% MODERNA 2225 4,14% 1375 2,56% 3600 6,70% Vaccino 68,22% 31,78% PFIZER 25412 47,32% 15671 29,18% 41083 76,51% PFIZER Comune di Gagliano Castelferrato (EN) Prot. N.0004568 del 04-05-2021 arrivo Cat14 Cl.1 Fascicolo ASTRAZENECA Totale 36636 68,22% 17063 31,78% 53699 100,00% MODERNA 53699 475,21 41,08K (76,51%) 0% 50% 100% Totale somministrazioni Media giornaliera Somministrazioni / Periodo selezionato Centro vaccinazione Somministrazioni per centro di 31/12/2020 29/04/2021 vaccinazione Tutte Somministrazioni per centro vaccinale Somministrazioni per centro vaccinale 2,3K Vaccino ASTRAZENECA MODERNA PFIZER Totale 2,4K (4,46%) (4,28%) Città 1 2 Totale -

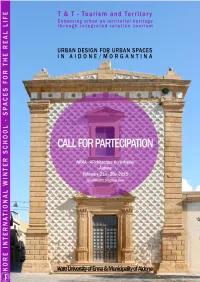

Call for Partecipation.Pdf

The Faculty of Engineering and Architecture at the ARKA Lab in Aidone offers the opportunity of a full- time research and didactic experience in enhancing urban & territorial heritage through Integrated Relational Tourism. An activity focused on the issue of Urban Design for Urban Spaces in Aidone/Morgantina as an opportunity aimed to improve the quality of life so as the local economic development for the communities of the inland rural areas. The Kore International Winter School 2015, represents a continuous of activities as interviews and meetings, workshops and expositions, lectures and site visits that, through 8 full days of common work, should explore problems and hopefully propose a range of visions for the future of the city and of the hinterland of Aidone-Morgantina and its heritage. The Kore International Winter School 2015 includes field trips and guided visits to the study site of Aidone and Morgantina, Piazza Armerina and Villa del Casale, Enna and Pergusa areas as well as social and cultural events. The School activities are articulated on three structural goals, which are: - the activity of scientific and applied Research, implicit in the proposed innovative approach as in the chosen application field; - the integrated project implementation Scenarios, as expected design results by the workshop; - the Training for new needed professionals, important to manage the transition to a different development model from the current one. Official and work languages Official language: English (for meetings, lectures, exibitions, etc.) Work languages: Arabic and Italian (for any other informal relationships!) Short Presentation The Winter School aims to promote a trans-disciplinary and international approach that encourages the development of skills and knowledge in the field of Integrated Tourism managed by the territory through its local actors and resources. -

Attitudes Towards the Safeguarding of Minority Languages and Dialects in Modern Italy

ATTITUDES TOWARDS THE SAFEGUARDING OF MINORITY LANGUAGES AND DIALECTS IN MODERN ITALY: The Cases of Sardinia and Sicily Maria Chiara La Sala Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds Department of Italian September 2004 This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. The candidate confirms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. ABSTRACT The aim of this thesis is to assess attitudes of speakers towards their local or regional variety. Research in the field of sociolinguistics has shown that factors such as gender, age, place of residence, and social status affect linguistic behaviour and perception of local and regional varieties. This thesis consists of three main parts. In the first part the concept of language, minority language, and dialect is discussed; in the second part the official position towards local or regional varieties in Europe and in Italy is considered; in the third part attitudes of speakers towards actions aimed at safeguarding their local or regional varieties are analyzed. The conclusion offers a comparison of the results of the surveys and a discussion on how things may develop in the future. This thesis is carried out within the framework of the discipline of sociolinguistics. ii DEDICATION Ai miei figli Youcef e Amil che mi hanno distolto -

Debunking Rhaeto-Romance: Synchronic Evidence from Two Peripheral Northern Italian Dialects

A corrigendum relating to this article has been published at ht De Cia, S and Iubini-Hampton, J 2020 Debunking Rhaeto-Romance: Synchronic Evidence from Two Peripheral Northern Italian Dialects. Modern Languages Open, 2020(1): 7 pp. 1–18. DOI: https://doi. org/10.3828/mlo.v0i0.309 ARTICLE – LINGUISTICS Debunking Rhaeto-Romance: Synchronic tp://doi.org/10.3828/mlo.v0i0.358. Evidence from Two Peripheral Northern Italian Dialects Simone De Cia1 and Jessica Iubini-Hampton2 1 University of Manchester, GB 2 University of Liverpool, GB Corresponding author: Jessica Iubini-Hampton ([email protected]) tp://doi.org/10.3828/mlo.v0i0.358. This paper explores two peripheral Northern Italian dialects (NIDs), namely Lamonat and Frignanese, with respect to their genealogical linguistic classification. The two NIDs exhibit morpho-phonological and morpho-syntactic features that do not fall neatly into the Gallo-Italic sub-classification of Northern Italo-Romance, but resemble some of the core characteristics of the putative Rhaeto-Romance language family. This analysis of Lamonat and Frignanese reveals that their con- servative traits more closely relate to Rhaeto-Romance. The synchronic evidence from the two peripheral NIDs hence supports the argument against the unity and autonomy of Rhaeto-Romance as a language family, whereby the linguistic traits that distinguish Rhaeto-Romance within Northern Italo-Romance consist A corrigendum relating to this article has been published at ht of shared retentions rather than shared innovations, which were once common to virtually all NIDs. In this light, Rhaeto-Romance can be regarded as an array of conservative Gallo-Italic varieties. -

Prefettura Di Enna Ufficio Territoriale Del Governo

Prefettura di Enna Ufficio territoriale del Governo ELENCO FORNITORI, PRESTATORI DI SERVIZI ED ESECUTORI DI LAVORI NON SOGGETTI A TENTATIVO DI INFILTRAZIONE MAFIOSA (Art. 1, commi dal 52 al 57, della legge n.190/2012; D.P.C.M. 18 aprile 2013) Sezione 10 SERVIZI AMBIENTALI, COMPRESE LE ATTIVITA' DI RACCOLTA, DI TRASPORTO NAZIONALE E TRANSFRONTALIERO, ANCHE PER CONTO DI TERZI, DI TRATTAMENTO E DI SMALTIMENTO DEI RIFIUTI, NONCHE' LE ATTIVITA' DI RISANAMNETO E DI BONIFICA E GLI ALTRI SERVIZI CONNESSI ALLA GESTIONE DEI RIFIUTI RAGIONE SEDE CODICE FISCALE DATA DI DATA SCADENZA NOTE SOCIALE LEGALE / PARTITA IVA ISCRIZIONE ISCRIZIONE 6 C M S.R.L. NICOSIA (EN) - VIA MAMMAFIGLIA N. 1 01186040869 13/02/2019 29/03/2022 ALEO GIUSEPPE CLAUDIO & C. S.N.C. BARRAFRANCA (EN) - VIA MASTROBUONO N. 15 00563470863 07/10/2015 16/11/2021 ALF SERVICES DI OTTIMO FABIO ENNA - STRADA COMUNALE S.C.49S.CATERINA VOLTA PALUMBO 181 D 01258530862 05/06/2020 04/06/2021 AN.SA. S.R.L. REGALBUTO (EN) - CONTRADA MANCHE SAVARINO SN 00672560869 22/08/2016 16/03/2022 ARENA MOVIMENTO TERRA S.R.L. ENNA - STRADA COMUNALE 193 BARRESI-BERARDI 799 01282350865 08/01/2021 07/01/2022 ASARESI S.N.C. DI ASARESI SALVATORE E C. BARRAFRANCA (EN) - VIA F.P. DI BLASI N. 21 00520600867 31/03/2021 30/03/2022 ATTARDI ANTONIO TROINA (EN) - VIA SOLLIMA N. 98 00372000869 09/02/2021 08/02/2022 ATTARDI GROUP S.R.L. TROINA (EN) - VIA SOLLIMA N. 98 01036560868 07/08/2018 29/03/2022 ATTARDI PAOLO ENNA - CONTRADA POLLICARINI SNC 01252270861 20/11/2018 03/03/2021 AUTOTRASPORTI C/TERZI DI ALLEGRO LUIGI & C. -

Piano Di Zona 2018/2019

“Il Paese è di tutti …ognuno di noi nel suo piccolo può dare e fare tanto per aiutarlo a crescere. Anche il mare è composto da tante piccole gocce…” PIANO DI ZONA 2018/2019 1 Lottate per la felicità Come lottano gli uomini per il grano. Ricordate che l’amore È il seme e il frutto della gioia. Amate gli altri perché gli altri Possano amarvi, amate voi stessi per poter amare gli altri. Non avrete paura della fame Perché troverete nei granai Il grano per gli anni magri. Non avrete paura del lavoro Perché vi sarà congeniale. Non avrete paura della vita Perché vi darà la vita E vi farà gioire della sua fertilità. Non avrete paura della morte perché in ogni orizzonte troverete una nuova saggezza. Ricordate l’altra sponda Del fiume dove un giorno Sarete misurati secondo il peso Del vostro cuore. Amen Maat II, 2330 a.c. PROCESSO DI FORMAZIONE DEL PIANO DI ZONA 2 Le azioni intraprese per favorire il processo di formazione del Piano sono state le seguenti: FASI ORGANISMI AZIONI Gruppo Piano Ha • aggiornato la relazione sociale redatta in sede di programmazione 2013/2015 secondo i criteri e le linee di indirizzo di cui all’Indice Ragionato per la predisposizione dei Piani di Zona, nonché la relazione allegata alla ultima implementazione del pdz ; • promosso, tramite il comune 1 capofila, le attività di concertazione; • definito, sulla base delle risultanze della relazione sociale e delle attività di concertazione, la proposta organica di implementazione dei servizi previsti o non previsti nel corrente Piano di Zona e nella successiva implementazione, utilizzando le risorse assegnate che è stata inoltrata al Comitato dei Sindaci.