Rat Colonization and Polynesian Voyaging: Another Hypothesis Atholl Anderson Australian National University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Honolulu Advertiser & Star-Bulletin Obituaries January 1

Honolulu Advertiser & Star-Bulletin Obituaries January 1 - December 31, 2001 T KATERINA GAEA TA'A, 74, of Waipahu, died Dec. 26, 2001. Born in American Samoa. Survived by sons, Siitia, Albert, Veni, John and Lemasaniai Gaea; daughter, Katerina Palaita and Cassandra Soa; 26 grandchildren; 12 great-grandchildren; brothers, Sefo, Atamu and Samu Gaea; sisters, Iutita Faamausili, Siao Howard, Senouefa Bartley, Vaalele Bomar, Vaatofu Dixon and Piuai Glenister. Visitation 6 to 9 p.m. Sunday at Mililani Mortuary Mauka Chapel; service 6:30 p.m. Service also 10 a.m. Monday at the mortuary; burial 12:30 p.m. at Mililani Memorial Park. Casual attire. [Adv 17/1/2002] Clarence Tenki Taba, a longtime banker and World War II veteran, died last Thursday July 19, 2001 in Honolulu. He was 79. Taba was born April 7, 1922, in Lahaina, Maui, as the fifth of 13 children. During the war, he was awarded two Bronze Stars and a Silver Star for courage in combat, and a Purple Heart with two Oak Leaf Clusters for injuries in three battles. He was a first sergeant in the Army. He worked with banks until retiring in 1997, first as a senior bank examiner for the Territory of Hawai'i and later in management positions with private banks such as City Bank and Bank of Hawai'i. He then served the Hawai'i Bankers Association for 22 years, helping to write bank legislation. His work with banks helped him establish a savings and loan program for the 442nd Veterans Club, where he was treasurer, vice president and president. -

A Linguistic Ethnography of Laissez Faire Translanguaging in Two High School English Classes

A LINGUISTIC ETHNOGRAPHY OF LAISSEZ FAIRE TRANSLANGUAGING IN TWO HIGH SCHOOL ENGLISH CLASSES A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATION DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN SECOND LANGUAGE STUDIES MAY 2020 By Anna Mendoza Dissertation Committee: Christina Higgins – Chairperson Betsy Gilliland Graham Crookes Sarah Allen Georganne Nordstrom ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dr. Christina Higgins, Dr. Betsy Gilliland, Dr. Graham Crookes, Dr. Sarah Allen, and Dr. Georganne Nordstrom for having my back through this whole process and being so collegial with each other. A dissertation is already an immense challenge; you did not make it any more difficult. On the contrary, you made the dissertation fun to write and revise (in the sense that such a process can be) and of high quality. I would also like to thank the College of Languages, Linguistics and Literature for funding this research with the 2019 Doctoral Dissertation Research Award. It is not only the financial award but the knowledge that others find my study important that I find encouraging. I am grateful for the invitation to present a keynote lecture at the 2019 College of LLL Conference to share my research with the public. I am most thankful to the principal, teachers, and students at the school where I did my study, who for reasons of confidentiality cannot be named here. I am amazed at the teachers’ curricular and extracurricular dedication, the creative and critical projects they shared at conferences. I also thank my Ilokano translator, Mario Doropan, who made this study possible. -

Polynesian Origins and Migrations: Aspects of the Mormon View And

polynesian ORIGINS AND migrations ASPECTS OF THE MORMON 2 VIEW AND contemporary scholarship by dr jerry K loveland harothhagoth has been presumed by some to be the hawaii loa of hawaiian the thesis of this paper is the latterlatterdayday saints view that the traditions and a book of mormon and american ancestor of the polynesian polynesians have ancestors from the americas can be supported by scientific people Moreomoreoververi more modern authorities that is authorities of the evidence however the same type of evidence indicates that the great bulk church has cited harothhagoth as an ancestor of the polynesiansPolyne sians Patriarchpatriarchialpatriarchicalial of the antecedents of this culture and of the polynesian people have their blessings that are conferred upon faithful latterlatterdayday saints have declared origins somewhere in asia harothhagoth by IDSLDS traditions an ancestor of the that polynesians are of the house of manasseh one of the children of polynesians and a book of mormon character cannot by scientific evidence joseph manasseh was the forefather of lehi the book of mormon prophet be linked with an known migration into or within polynesia incomplete and who migrated with his family from jerusalem to the american continent in frequently hazy polynesian traditions however do support the contention 600 BC that there was in prehistoric times a contact with poepledoeplewho knew of the so much for the position of the church now what does modern biblical account of the patriarchs and the peoples of the old testament science -

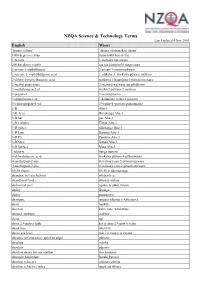

NZQA Science & Technology Terms

NZQA Science & Technology Terms Last Updated 4 Nov 2010 English Māori ‘fitness culture’ ‘ahurea whakapakari tinana’ 1000 degrees celsius mano takiri henekereti 1-hexene 1-waiwaro rua owaro 200 km above (earth) rua rau kiromita ki runga rawa 2-amino-3-methylbutane 2-amino-3-mewarop ūwaro 2–bromo–3–methylbutanoic acid 2–pūkeha–3–waikawa p ūwaro m ēwaro 2-chloro-3-methylbutanoic acid waikawa 2-haum āota-3-pūwaro mewaro 2-methyl propenoate 2-mewaro waiwaro rua p ōhākawa 2-methylpropan-2-ol waihä-2-pöwaro-2-mewaro 2-propanol 2-waih ā p ōwaro 3-chlorobutan-1-ol 3-haum āota waih ā-1-pūwaro 3–chloropropan–1–ol 3–waih ā–1–pōwaro p ūhaum āota 3-D Ahu-3 3-D Area Horahanga Ahu-3 3-D bar pae Ahu-3 3-D Column Tīwae Ahu-3 3-D effect rākeitanga Ahu-3 3-D Line Rārangi Ahu-3 3-D Pie Porohita Ahu-3 3-D Style Kāhua Ahu-3 3-D Surface Mata Ahu-3 3rd party hunga tuatoru 4-chlorobutanoic acid waikawa p ūwaro 4-pūhaum āota 4-methylpent-2-ene 4-waiwaro-rua-2-pēwaro mewaro 4-methylpent-2-yne 4-waiwaro-toru-2-pēwaro mewaro 50-50 chance 50-50 te t ūponotanga abandon, to leave behind whakar ērea abandoned (land) whenua mahue abdominal pain ngau o te puku, k ōpito ability āheinga ability pūmanawa aborigine tangata whenua o Ahitereiria abort haukoti abortion kuka, tahe, whakatahe abound, multiply makuru about mō about 2.4 metres high kei te āhua 2.4 mita te teitei about face tahuri k ē above sea level mai i te mata o te moana abrasive (of character), quick to anger pūtiotio absolute mārika absolute pūrawa absolute desire for one another tara koukoua Absolute Magnitude -

Uhm Phd 9532628 R.Pdf

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type ofcomputer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to beremoved, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. MI48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 The Marine Realm and a Sense of Place Among the Papua New Guinean Communities ofthe Torres Strait A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN GEOGRAPHY MAY 1995 By Donald M. -

View Sample Pages of Tangata O Le Moana

Edited by Sean Mallon, Kolokesa Māhina-Tuai and Damon Salesa First published in New Zealand in 2012 by Te Papa Press, P O Box 467, Wellington, New Zealand Text © Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa and the contributors Images © Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa or as credited This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism, or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part of this book may be reproduced by any process, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, without the prior permission of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. TE PAPA® is the trademark of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa Te Papa Press is an imprint of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa Tangata o le moana : New Zealand and the people of the Pacific / edited by Sean Mallon, Kolokesa Māhina-Tuai and Damon Salesa. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-877385-72-8 [1. Pacific Islanders—New Zealand. 2. Pacific Islanders—New Zealand—History.] I. Mallon, Sean. II. Māhina-Tuai, Kolokesa Uafā. III. Salesa, Damon Ieremia, 1972- IV. Title. 305.8995093—dc 22 Design by Spencer Levine Digital imaging by Jeremy Glyde Printed by Everbest Printing Co, China Cover: All images are selected from the pages of Tangata o le Moana. Back cover: Tokelauans leaving for New Zealand, 1966. Opposite: Melanesian missionary scholars and cricket players from Norfolk Island with the Bishop of Melanesia, Cecil Wilson, at the home of the Bishop of Christchurch, 1895. -

Cultural Etiquette in the Pacific Guidelines for Staff Working in Pacific Communities Tropic of Cancer Tropique Du Cancer HAWAII NORTHERN MARIANA ISLANDS

Cultural Etiquette in the Pacific Guidelines for staff working in Pacific communities Tropic of Cancer Tropique du Cancer HAWAII NORTHERN MARIANA ISLANDS GUAM MARSHALL PALAU ISLANDS BELAU Pacic Ocean FEDERATED STATES Océan Pacifique OF MICRONESIA PAPUA NEW GUINEA KIRIBATI NAURU KIRIBATI KIRIBATI TUVALU SOLOMON TOKELAU ISLANDS COOK WALLIS & SAMOA ISLANDS FUTUNA AMERICA SAMOA VANUATU NEW FRENCH CALEDONIA FIJI NIUE POLYNESIA TONGA PITCAIRN ISLANDS AUSTRALIA RAPA NUI/ NORFOLK EASTER ISLAND ISLAND Tasman Sea Mer De Tasman AOTEAROA/ NEW ZEALAND Tropic of Cancer Tropique du Cancer HAWAII NORTHERN MARIANA ISLANDS GUAM MARSHALL PALAU ISLANDS BELAU Pacic Ocean FEDERATED STATES Océan Pacifique OF MICRONESIA PAPUA NEW GUINEA KIRIBATI NAURU KIRIBATI KIRIBATI TUVALU SOLOMON TOKELAU ISLANDS COOK WALLIS & SAMOA ISLANDS FUTUNA AMERICA SAMOA VANUATU NEW FRENCH CALEDONIA FIJI NIUE POLYNESIA TONGA PITCAIRN ISLANDS AUSTRALIA RAPA NUI/ NORFOLK EASTER ISLAND ISLAND Tasman Sea Mer De Tasman AOTEAROA/ NEW ZEALAND Cultural Etiquette in the Pacific Guidelines for staff working in Pacific communities Noumea, New Caledonia, 2020 Look out for these symbols for quick identification of areas of interest. Leadership and Protocol Daily Life Background Religion Protocol Gender Ceremonies Dress Welcoming ceremonies In the home Farewell ceremonies Out and about Kava ceremonies Greetings Other ceremonies Meals © Pacific Community (SPC) 2020 All rights for commercial/for profit reproduction or translation, in any form, reserved. SPC authorises the partial reproduction or translation of this material for scientific, educational or research purposes, provided that SPC and the source document are properly acknowledged. Permission to reproduce the document and/or translate in whole, in any form, whether for commercial/for profit or non-profit purposes, must be requested in writing. -

Yaneva-Toraman2020 Redacted.Pdf (5.685Mb)

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. FACES OF SHAME, MASKS OF DEVELOPMENT: RECOGNITION AND OIL PALM AMONG THE BAINING OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA Inna Yaneva-Toraman PhD Social Anthropology The University of Edinburgh 2019 1 Declaration I declare that this thesis has been composed solely by myself and that no part of it has been submitted in any previous application for a degree or professional qualification. Except where I state otherwise by reference or acknowledgment, the work presented is entirely my own. Signature: Inna Zlatimirova Yaneva-Toraman September 2019, Edinburgh UK 2 3 Abstract This thesis explores the role of “shame” in the Vir Kairak Baining people’s understanding of the relationships that underpin positive social change. Previous studies of shame in the context of colonial and postcolonial transformation in Melanesia have suggested that encounters with outsiders humiliated local communities and incited their cultural and economic conversion. -

ED407050.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 407 050 JC 970 280 TITLE University of Hawaii Community Colleges Annual Report, 1990-91. Academic Year 1990-91 (September 3, 1990 to May 28, 1991) and Fiscal Year 1990-91 (July 1, 1990 to June 30, 1991) INSTITUTION Hawaii Univ., Honolulu. Office of the Chancellor for Community Colleges. PUB DATE 91 NOTE 40p.; For a series of these annual reports covering 1988 to 1992/93, see JC 970 278-282. Photographs may not reproduce clearly. PUB TYPE Numerical/Quantitative Data (110) Reports Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Associate Degrees; Community Colleges; Educational Certificates; *Educational Finance; *Enrollment; *Institutional Characteristics; *Institutional Mission; Mission Statements; Outcomes of Education; Student Characteristics; Teacher Characteristics; *Two Year College Students; Two Year Colleges IDENTIFIERS *University of Hawaii Community College System ABSTRACT Providing information on programs, students, and faculty at the University of Hawaii Community Colleges, this report reviews data for the 1990-91 academic and fiscal years (FYs). The first section reviews systemwide accomplishments for the year, describes efforts related to international education, and presents an agenda for action. The organizational structure and mission of the colleges are then presented and 1990-91 data are provided on enrollment, degrees and certificates awarded, tuition, general funds appropriations, programs of study, disciplines, special programs and community services, and student and faculty characteristics. -

Indigenous and Decolonizing Studies in Education

INDIGENOUS AND DECOLONIZING STUDIES IN EDUCATION Indigenous and decolonizing perspectives on education have long persisted alongside colonial models of education, yet too often have been subsumed within the fields of multiculturalism, critical race theory, and progressive education. Timely and compelling, Indigenous and Decolonizing Studies in Education features research, theory, and dynamic foundational readings for educators and educational researchers who are looking for possibilities beyond the limits of liberal democratic schooling. Featuring original chapters by authors at the forefront of theorizing, practice, research, and activism, this volume helps define and imagine the exciting interstices between Indigenous and decolonizing studies and education. Each chapter forwards Indigenous principles—such as Land as literacy and water is life—that are grounded in place-specific efforts of creating Indigenous universities and schools, community organizing and social movements, trans and Two Spirit practices, refusals of state policies, and land-based and water-based pedagogies. Linda Tuhiwai Smith is a Professor of Māori and Indigenous Studies at the University of Waikato in New Zealand. Eve Tuck is Associate Professor of Critical Race and Indigenous Studies, Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, and Canada Research Chair of Indigenous Methodologies with Youth and Communities, University of Toronto. K. Wayne Yang is the Director of Undergraduate Studies in the Ethnic Studies Department at the University of California, San Diego. Indigenous and Decolonizing Studies in Education Series Editors: Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang Indigenous and Decolonizing Studies in Education Mapping the Long View Edited by Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Eve Tuck, and K. Wayne Yang INDIGENOUS AND DECOLONIZING STUDIES IN EDUCATION Mapping the Long View Edited by Linda Tuhiwai Smith Eve Tuck K. -

Notice of Names of Persons Appearing to Be Owners of Abandoned Property

NOTICE OF NAMES OF PERSONS APPEARING TO BE OWNERS OF ABANDONED PROPERTY Pursuant to Chapter 523A, Hawaii Revised Statutes, and based upon reports filed with the Director of Finance, State of Hawaii, the names of persons appearing to be the owners of abandoned property are listed in this notice. The term, abandoned property, refers to personal property such as: dormant savings and checking accounts, shares of stock, uncashed payroll checks, uncashed dividend checks, deposits held by utilities, insurance and medical refunds, and safe deposit box contents that, in most cases, have remained inactive for a period of at least 5 years. Abandoned property, as used in this context, has no reference to real estate. Reported owner names are separated by county: Honolulu; Kauai; Maui; Hawaii. Reported owner names appear in alphabetical order together with their last known address. A reported owner can be listed: last name, first name, middle initial or first name, middle initial, last name or by business name. Owners whose names include a suffix, such as Jr., Sr., III, should search for the suffix following their last name, first name or middle initial. Searches for names should include all possible variations. OWNERS OF PROPERTY PRESUMED ABANDONED SHOULD CONTACT THE UNCLAIMED PROPERTY PROGRAM TO CLAIM THEIR PROPERTY Information regarding claiming unclaimed property may be obtained by visiting: http://budget.hawaii.gov/finance/unclaimedproperty/owner-information/. Information concerning the description of the listed property may be obtained by calling the Unclaimed Property Program, Monday – Friday, 7:45 am - 4:30 pm, except State holidays at: (808) 586-1589. If you are calling from the islands of Kauai, Maui or Hawaii, the toll-free numbers are: Kauai 274-3141 Maui 984-2400 Hawaii 974-4000 After calling the local number, enter the extension number: 61589. -

SPC Fisheries Newsletter #162 - May–August 2020 • SPC Activities •

Fisheries # 162 May–August 2020 Newsletter ISSN: 0248-0735 SPC activities Regional news Feature articles FAME Fisheries, Aquaculture and Marine Ecosystems Division In this issue SPC activities 3 How the Pacific Community contributes to the annual WCPFC Scientific Committee meeting by Graham Pilling 6 Back to the ocean by Bruno Leroy and Valérie Allain Let them go: Release undersized, untargeted or unwanted fish! 10 by Céline Muron and William Sokimi From luxury lotions to tasty local dishes 13 by Avinash Singh Tilapia feed trials conducted at the Navuso Agricultural Technical Institute in Fiji 14 by Avinash Singh News from in and around the region The return of the true giant clam to Kosrae 16 by Martin Selch A roadmap for electronic monitoring in regional fishery management organisations 17 by Mark Michelin et al. A survey of the number of coastal fishing vessels in Fiji 23 by Robert Gillett Using local knowledge to guide coconut crab science in Fiji 27 by Epeli Loganimoce et al. Developing participatory monitoring of community fisheries in Kiribati and Vanuatu 32 by Neil Andrew et al. A novel participatory catch monitoring approach: The Vanuatu experience 39 by Abel Sami et al. Feature articles Population genetics: Basics and future applications to fisheries science in the Pacific 46 by Giuliana Anderson et al. 58 Spawning potential surveys in Solomon Islands’ Western Province Cover picture: Leonard Loga, coconut crab hunter, feeding one of his catch before packing it, Naqelelevu Island, Fiji (Image: ©Epeli Loganimoce, IMR USP) (Image: packing ©Epeli Loganimoce, Fiji it, Naqelelevu before Island, one of his catch feeding coconut crab hunter, Loga, picture: Leonard Cover by Jeremy Prince et al.