Yaneva-Toraman2020 Redacted.Pdf (5.685Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Honolulu Advertiser & Star-Bulletin Obituaries January 1

Honolulu Advertiser & Star-Bulletin Obituaries January 1 - December 31, 2001 T KATERINA GAEA TA'A, 74, of Waipahu, died Dec. 26, 2001. Born in American Samoa. Survived by sons, Siitia, Albert, Veni, John and Lemasaniai Gaea; daughter, Katerina Palaita and Cassandra Soa; 26 grandchildren; 12 great-grandchildren; brothers, Sefo, Atamu and Samu Gaea; sisters, Iutita Faamausili, Siao Howard, Senouefa Bartley, Vaalele Bomar, Vaatofu Dixon and Piuai Glenister. Visitation 6 to 9 p.m. Sunday at Mililani Mortuary Mauka Chapel; service 6:30 p.m. Service also 10 a.m. Monday at the mortuary; burial 12:30 p.m. at Mililani Memorial Park. Casual attire. [Adv 17/1/2002] Clarence Tenki Taba, a longtime banker and World War II veteran, died last Thursday July 19, 2001 in Honolulu. He was 79. Taba was born April 7, 1922, in Lahaina, Maui, as the fifth of 13 children. During the war, he was awarded two Bronze Stars and a Silver Star for courage in combat, and a Purple Heart with two Oak Leaf Clusters for injuries in three battles. He was a first sergeant in the Army. He worked with banks until retiring in 1997, first as a senior bank examiner for the Territory of Hawai'i and later in management positions with private banks such as City Bank and Bank of Hawai'i. He then served the Hawai'i Bankers Association for 22 years, helping to write bank legislation. His work with banks helped him establish a savings and loan program for the 442nd Veterans Club, where he was treasurer, vice president and president. -

A Distinctive Voice in the Antipodes: Essays in Honour of Stephen A. Wild

ESSAYS IN HONOUR OF STEPHEN A. WILD Stephen A. Wild Source: Kim Woo, 2015 ESSAYS IN HONOUR OF STEPHEN A. WILD EDITED BY KIRSTY GILLESPIE, SALLY TRELOYN AND DON NILES Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: A distinctive voice in the antipodes : essays in honour of Stephen A. Wild / editors: Kirsty Gillespie ; Sally Treloyn ; Don Niles. ISBN: 9781760461119 (paperback) 9781760461126 (ebook) Subjects: Wild, Stephen. Essays. Festschriften. Music--Oceania. Dance--Oceania. Aboriginal Australian--Songs and music. Other Creators/Contributors: Gillespie, Kirsty, editor. Treloyn, Sally, editor. Niles, Don, editor. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover photograph: ‘Stephen making a presentation to Anbarra people at a rom ceremony in Canberra, 1995’ (Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies). This edition © 2017 ANU Press A publication of the International Council for Traditional Music Study Group on Music and Dance of Oceania. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are advised that this book contains images and names of deceased persons. Care should be taken while reading and viewing. Contents Acknowledgements . vii Foreword . xi Svanibor Pettan Preface . xv Brian Diettrich Stephen A . Wild: A Distinctive Voice in the Antipodes . 1 Kirsty Gillespie, Sally Treloyn, Kim Woo and Don Niles Festschrift Background and Contents . -

The Wheel of Vitality: an Approach to Rapid Vitality Assessment in New Britain

DigitalResources Electronic Survey Report 2014-010 The Wheel of Vitality An Approach to Rapid Vitality Assessment in New Britain John Grummitt The Wheel of Vitality: An approach to rapid vitality assessment in New Britain John Grummitt SIL International® 2014 SIL Electronic Survey Report 2014-010, November 2014 © 2014 SIL International® All rights reserved Abstract In a recent survey, sub-goals determined by stakeholders’ needs were dependent on the main goal of assessing an agreed minimum vitality level. This vitality level was the determining factor for the inclusion of five language communities in a proposed multi-language development project. This dependence created a need for an in situ rapid vitality assessment to determine whether pursuit of sub- goals was necessary. This report describes the development of a tool based on the Expanded Graded Intergenerational Disruption Scale vitality scale and used to rapidly assess vitality in an environment where logistical constraints made traditional and more detailed vitality assessment unfeasible. Contents Abstract 1 Introduction 1.1 Survey Need 1.2 Survey Purpose and Goals 2 Methodology 2.1 Initial Approaches to Tool Design 2.2 Tool Description and Administration 3 Critique 4 Conclusion Appendix A Original Rubric for the Wheel of Vitality Tool Appendix B Original Wheel of Vitality Data Collection Sheet Appendix C Observation Schedule References iii 1 Introduction 1.1 Survey Need In the planning of a multi-language project aiming to “ensure that all the language communities on New Britain have access to adequate…materials in the languages that serve them well” (Wiebe and Wiebe 2009:1), the SIL Papua New Guinea (PNG) survey team was asked to assess five language communities which had no established language development programs. -

Rat Colonization and Polynesian Voyaging: Another Hypothesis Atholl Anderson Australian National University

Rapa Nui Journal: Journal of the Easter Island Foundation Volume 10 Article 1 Issue 2 June 1996 1996 Rat Colonization and Polynesian Voyaging: another hypothesis Atholl Anderson Australian National University Follow this and additional works at: https://kahualike.manoa.hawaii.edu/rnj Part of the History of the Pacific slI ands Commons, and the Pacific slI ands Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Anderson, Atholl (1996) "Rat Colonization and Polynesian Voyaging: another hypothesis," Rapa Nui Journal: Journal of the Easter Island Foundation: Vol. 10 : Iss. 2 , Article 1. Available at: https://kahualike.manoa.hawaii.edu/rnj/vol10/iss2/1 This Research Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Hawai`i Press at Kahualike. It has been accepted for inclusion in Rapa Nui Journal: Journal of the Easter Island Foundation by an authorized editor of Kahualike. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Anderson: Rat Colonization and Polynesian Voyaging: another hypothesis Rat Colonization and Polynesian Voyaging: another hypothesis Atholl Ander on Division ofArchaeology and Na/ural His/OIY, Australian National University Robert Langdon (1995:77) disputes the long-standing Humboldt connecting these islands with New Zealand, and proposition that Rattus exulans was dispersed by Polynesian few large rafts of vegetation are debauched by their rivers voyaging and suggests tbat over hundreds of thousands or (there could bave been logs, but tbese are bigbly unstable in millions of years it "succeeded in getting from one island to a seaway), the probability of a successful natural drift event another witbout any human aid at aiL." Between this and the occurring during a maximum timespan of 2000 years before conventional view lies the possibility, not yet explored in demonstrated buman settlement of New Zealand, cannot be detail, that some rats were transported on canoes that had lost bigh. -

A Linguistic Ethnography of Laissez Faire Translanguaging in Two High School English Classes

A LINGUISTIC ETHNOGRAPHY OF LAISSEZ FAIRE TRANSLANGUAGING IN TWO HIGH SCHOOL ENGLISH CLASSES A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATION DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN SECOND LANGUAGE STUDIES MAY 2020 By Anna Mendoza Dissertation Committee: Christina Higgins – Chairperson Betsy Gilliland Graham Crookes Sarah Allen Georganne Nordstrom ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dr. Christina Higgins, Dr. Betsy Gilliland, Dr. Graham Crookes, Dr. Sarah Allen, and Dr. Georganne Nordstrom for having my back through this whole process and being so collegial with each other. A dissertation is already an immense challenge; you did not make it any more difficult. On the contrary, you made the dissertation fun to write and revise (in the sense that such a process can be) and of high quality. I would also like to thank the College of Languages, Linguistics and Literature for funding this research with the 2019 Doctoral Dissertation Research Award. It is not only the financial award but the knowledge that others find my study important that I find encouraging. I am grateful for the invitation to present a keynote lecture at the 2019 College of LLL Conference to share my research with the public. I am most thankful to the principal, teachers, and students at the school where I did my study, who for reasons of confidentiality cannot be named here. I am amazed at the teachers’ curricular and extracurricular dedication, the creative and critical projects they shared at conferences. I also thank my Ilokano translator, Mario Doropan, who made this study possible. -

Customary Land Tenure and Registration in Australia and Papua New Guinea: Anthropological Perspectives

Asia-Pacific Environment Monograph 3 Customary Land Tenure and Registration in Australia and Papua New Guinea: Anthropological Perspectives Asia-Pacific Environment Monograph 3 Customary Land Tenure and Registration in Australia and Papua New Guinea: Anthropological Perspectives Edited by James F. Weiner and Katie Glaskin Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/customary_citation.html National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Customary land tenure and registration in Australia and Papua New Guinea : anthropological perspectives. Bibliography. ISBN 9781921313264 (pbk.) ISBN 9781921313271 (online) 1. Aboriginal Australians - Land tenure - Social aspects - Australia. 2. Papuans - Land tenure - Social aspects - Papua New Guinea. 3. Land titles - Registration and transfer - Australia. 4. Land titles - Registration and transfer - Papua New Guinea. 5. Land use - History - Australia. 6. Land use - History - Papua New Guinea. I. Weiner, James F. II. Glaskin, Katie. (Series : APEM Monographs Series). 306.32 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by Duncan Beard. Cover photograph: Landowner of Goare Village, Goaribari Island, Gulf Province, Papua New Guinea (photo by James F. Weiner). This edition © 2007 ANU E Press Table of Contents Foreword ix Abbreviations xv Contributors xvii 1. Customary Land Tenure and Registration in Papua New Guinea and Australia: Anthropological Perspectives, James F. Weiner and Katie Glaskin 1 2. A Legal Regime for Issuing Group Titles to Customary Land: Lessons from the East Sepik, Jim Fingleton 15 3. -

Polynesian Origins and Migrations: Aspects of the Mormon View And

polynesian ORIGINS AND migrations ASPECTS OF THE MORMON 2 VIEW AND contemporary scholarship by dr jerry K loveland harothhagoth has been presumed by some to be the hawaii loa of hawaiian the thesis of this paper is the latterlatterdayday saints view that the traditions and a book of mormon and american ancestor of the polynesian polynesians have ancestors from the americas can be supported by scientific people Moreomoreoververi more modern authorities that is authorities of the evidence however the same type of evidence indicates that the great bulk church has cited harothhagoth as an ancestor of the polynesiansPolyne sians Patriarchpatriarchialpatriarchicalial of the antecedents of this culture and of the polynesian people have their blessings that are conferred upon faithful latterlatterdayday saints have declared origins somewhere in asia harothhagoth by IDSLDS traditions an ancestor of the that polynesians are of the house of manasseh one of the children of polynesians and a book of mormon character cannot by scientific evidence joseph manasseh was the forefather of lehi the book of mormon prophet be linked with an known migration into or within polynesia incomplete and who migrated with his family from jerusalem to the american continent in frequently hazy polynesian traditions however do support the contention 600 BC that there was in prehistoric times a contact with poepledoeplewho knew of the so much for the position of the church now what does modern biblical account of the patriarchs and the peoples of the old testament science -

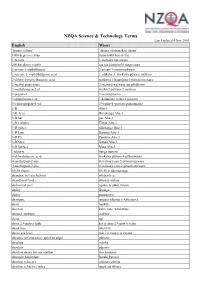

NZQA Science & Technology Terms

NZQA Science & Technology Terms Last Updated 4 Nov 2010 English Māori ‘fitness culture’ ‘ahurea whakapakari tinana’ 1000 degrees celsius mano takiri henekereti 1-hexene 1-waiwaro rua owaro 200 km above (earth) rua rau kiromita ki runga rawa 2-amino-3-methylbutane 2-amino-3-mewarop ūwaro 2–bromo–3–methylbutanoic acid 2–pūkeha–3–waikawa p ūwaro m ēwaro 2-chloro-3-methylbutanoic acid waikawa 2-haum āota-3-pūwaro mewaro 2-methyl propenoate 2-mewaro waiwaro rua p ōhākawa 2-methylpropan-2-ol waihä-2-pöwaro-2-mewaro 2-propanol 2-waih ā p ōwaro 3-chlorobutan-1-ol 3-haum āota waih ā-1-pūwaro 3–chloropropan–1–ol 3–waih ā–1–pōwaro p ūhaum āota 3-D Ahu-3 3-D Area Horahanga Ahu-3 3-D bar pae Ahu-3 3-D Column Tīwae Ahu-3 3-D effect rākeitanga Ahu-3 3-D Line Rārangi Ahu-3 3-D Pie Porohita Ahu-3 3-D Style Kāhua Ahu-3 3-D Surface Mata Ahu-3 3rd party hunga tuatoru 4-chlorobutanoic acid waikawa p ūwaro 4-pūhaum āota 4-methylpent-2-ene 4-waiwaro-rua-2-pēwaro mewaro 4-methylpent-2-yne 4-waiwaro-toru-2-pēwaro mewaro 50-50 chance 50-50 te t ūponotanga abandon, to leave behind whakar ērea abandoned (land) whenua mahue abdominal pain ngau o te puku, k ōpito ability āheinga ability pūmanawa aborigine tangata whenua o Ahitereiria abort haukoti abortion kuka, tahe, whakatahe abound, multiply makuru about mō about 2.4 metres high kei te āhua 2.4 mita te teitei about face tahuri k ē above sea level mai i te mata o te moana abrasive (of character), quick to anger pūtiotio absolute mārika absolute pūrawa absolute desire for one another tara koukoua Absolute Magnitude -

Uhm Phd 9532628 R.Pdf

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type ofcomputer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to beremoved, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. MI48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 The Marine Realm and a Sense of Place Among the Papua New Guinean Communities ofthe Torres Strait A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN GEOGRAPHY MAY 1995 By Donald M. -

View Sample Pages of Tangata O Le Moana

Edited by Sean Mallon, Kolokesa Māhina-Tuai and Damon Salesa First published in New Zealand in 2012 by Te Papa Press, P O Box 467, Wellington, New Zealand Text © Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa and the contributors Images © Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa or as credited This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism, or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part of this book may be reproduced by any process, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, without the prior permission of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. TE PAPA® is the trademark of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa Te Papa Press is an imprint of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa Tangata o le moana : New Zealand and the people of the Pacific / edited by Sean Mallon, Kolokesa Māhina-Tuai and Damon Salesa. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-877385-72-8 [1. Pacific Islanders—New Zealand. 2. Pacific Islanders—New Zealand—History.] I. Mallon, Sean. II. Māhina-Tuai, Kolokesa Uafā. III. Salesa, Damon Ieremia, 1972- IV. Title. 305.8995093—dc 22 Design by Spencer Levine Digital imaging by Jeremy Glyde Printed by Everbest Printing Co, China Cover: All images are selected from the pages of Tangata o le Moana. Back cover: Tokelauans leaving for New Zealand, 1966. Opposite: Melanesian missionary scholars and cricket players from Norfolk Island with the Bishop of Melanesia, Cecil Wilson, at the home of the Bishop of Christchurch, 1895. -

Cultural Etiquette in the Pacific Guidelines for Staff Working in Pacific Communities Tropic of Cancer Tropique Du Cancer HAWAII NORTHERN MARIANA ISLANDS

Cultural Etiquette in the Pacific Guidelines for staff working in Pacific communities Tropic of Cancer Tropique du Cancer HAWAII NORTHERN MARIANA ISLANDS GUAM MARSHALL PALAU ISLANDS BELAU Pacic Ocean FEDERATED STATES Océan Pacifique OF MICRONESIA PAPUA NEW GUINEA KIRIBATI NAURU KIRIBATI KIRIBATI TUVALU SOLOMON TOKELAU ISLANDS COOK WALLIS & SAMOA ISLANDS FUTUNA AMERICA SAMOA VANUATU NEW FRENCH CALEDONIA FIJI NIUE POLYNESIA TONGA PITCAIRN ISLANDS AUSTRALIA RAPA NUI/ NORFOLK EASTER ISLAND ISLAND Tasman Sea Mer De Tasman AOTEAROA/ NEW ZEALAND Tropic of Cancer Tropique du Cancer HAWAII NORTHERN MARIANA ISLANDS GUAM MARSHALL PALAU ISLANDS BELAU Pacic Ocean FEDERATED STATES Océan Pacifique OF MICRONESIA PAPUA NEW GUINEA KIRIBATI NAURU KIRIBATI KIRIBATI TUVALU SOLOMON TOKELAU ISLANDS COOK WALLIS & SAMOA ISLANDS FUTUNA AMERICA SAMOA VANUATU NEW FRENCH CALEDONIA FIJI NIUE POLYNESIA TONGA PITCAIRN ISLANDS AUSTRALIA RAPA NUI/ NORFOLK EASTER ISLAND ISLAND Tasman Sea Mer De Tasman AOTEAROA/ NEW ZEALAND Cultural Etiquette in the Pacific Guidelines for staff working in Pacific communities Noumea, New Caledonia, 2020 Look out for these symbols for quick identification of areas of interest. Leadership and Protocol Daily Life Background Religion Protocol Gender Ceremonies Dress Welcoming ceremonies In the home Farewell ceremonies Out and about Kava ceremonies Greetings Other ceremonies Meals © Pacific Community (SPC) 2020 All rights for commercial/for profit reproduction or translation, in any form, reserved. SPC authorises the partial reproduction or translation of this material for scientific, educational or research purposes, provided that SPC and the source document are properly acknowledged. Permission to reproduce the document and/or translate in whole, in any form, whether for commercial/for profit or non-profit purposes, must be requested in writing. -

Online Appendix To

Online Appendix to Hammarström, Harald & Sebastian Nordhoff. (2012) The languages of Melanesia: Quantifying the level of coverage. In Nicholas Evans & Marian Klamer (eds.), Melanesian Languages on the Edge of Asia: Challenges for the 21st Century (Language Documentation & Conservation Special Publication 5), 13-34. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ’Are’are [alu] < Austronesian, Nuclear Austronesian, Malayo- Polynesian, Central-Eastern Malayo-Polynesian, Eastern Malayo- Polynesian, Oceanic, Southeast Solomonic, Longgu-Malaita- Makira, Malaita-Makira, Malaita, Southern Malaita Geerts, P. 1970. ’Are’are dictionary (Pacific Linguistics: Series C 14). Canberra: The Australian National University [dictionary 185 pp.] Ivens, W. G. 1931b. A Vocabulary of the Language of Marau Sound, Guadalcanal, Solomon Islands. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies VI. 963–1002 [grammar sketch] Tryon, Darrell T. & B. D. Hackman. 1983. Solomon Islands Languages: An Internal Classification (Pacific Linguistics: Series C 72). Canberra: Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, Australian National University. Bibliography: p. 483-490 [overview, comparative, wordlist viii+490 pp.] ’Auhelawa [kud] < Austronesian, Nuclear Austronesian, Malayo- Polynesian, Central-Eastern Malayo-Polynesian, Eastern Malayo- Polynesian, Oceanic, Western Oceanic linkage, Papuan Tip linkage, Nuclear Papuan Tip linkage, Suauic unknown, A. (2004 [1983?]). Organised phonology data: Auhelawa language [kud] milne bay province http://www.sil.org/pacific/png/abstract.asp?id=49613 1 Lithgow, David. 1987. Language change and relationships in Tubetube and adjacent languages. In Donald C. Laycock & Werner Winter (eds.), A world of language: Papers presented to Professor S. A. Wurm on his 65th birthday (Pacific Linguistics: Series C 100), 393-410. Canberra: Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, Australian National University [overview, comparative, wordlist] Lithgow, David.