Science Supporting Marine Protected Areas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Coral Reef Environmental "Crisis": Negotiating Knowledge in Scientific Uncertainty and Geographic Difference Ba#Rbel G

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2010 The Coral Reef Environmental "Crisis": Negotiating Knowledge in Scientific Uncertainty and Geographic Difference Ba#rbel G. Bischof Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES & PUBLIC POLICY THE CORAL REEF ENVIRONMENTAL “CRISIS”: NEGOTIATING KNOWLEDGE IN SCIENTIFIC UNCERTAINTY AND GEOGRAPHIC DIFFERENCE By BÄRBEL G. BISCHOF A Dissertation submitted to the Department of Geography in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2010 i The members of the committee approve the dissertation of Bärbel G. Bischof, defended on May 7, 2010. !!!!!!_____________________________________________ !!!!!!Philip E. Steinberg !!!!!! Professor Directing Dissertation !!!!!!_____________________________________________ !!!!!!Ronald E. Doel !!!!!! University Representative !!! !!!!!!_____________________________________________ !!!!!!James B. Elsner !!!!!! Committee Member !!!!!!_____________________________________________ !!!!!!Xiaojun Yang !!!!!! Committee Member !!!!!! Approved: ______________________________________________________________ Victor Mesev, Chair, Department of Geography ______________________________________________________________ David W. Rasmussen, Dean, College of Social Sciences & Public Policy The Graduate School has verified and approved the -

The Honolulu Declaration on Ocean Acidification and Reef Management

The Honolulu Declaration on Ocean Acidification and Reef Management Prepared and adopted by participants of the Ocean Acidification Workshop, convened by The Nature Conservancy, 12-14 August 2008, Hawaii 1 IUCN Global Marine Programme Founded in 1948, The World Conservation Union brings together States, government agencies and a diverse range of non-governmental organizations in a unique world partnership: over 1000 members in all, spread across some 140 countries. As a Union, IUCN seeks to influence, encourage and assist societies throughout the world to conserve the integrity and diversity of nature and to ensure that any use of natural resources is equitable and ecologically sustainable. The IUCN Global Marine Programme provides vital linkages for the Union and its members to all the IUCN activities that deal with marine issues, including projects and initiatives of the Regional offices and the 6 IUCN Commissions. The IUCN Global Marine Programme works on issues such as integrated coastal and marine management, fisheries, marine protected areas, large marine ecosystems, coral reefs, marine invasives and protection of high and deep seas. The Nature Conservancy The mission of The Nature Conservancy is to preserve the plants, animals and natural communities that represent the diversity of life on Earth by protecting the lands and waters they need to survive. The Conservancy launched the Global Marine Initiative in 2002 to protect and restore the most resilient examples of ocean and coastal ecosystems in ways that benefit marine life, local communities and economies. The Conservancy operates over 100 marine conservation projects in more than 21 countries and 22 U.S. -

Submission from Dr Gideon Polya to the Senate Inquiry Into Australia's Faunal Extinction Crisis (12 August 2019). Credentials

Submission from Dr Gideon Polya to the Senate Inquiry into Australia’s Faunal Extinction Crisis (12 August 2019). Credentials. BSc (Zoology and Chemistry majors, University of Tasmania, 1965), BSc Honours (First Class, University of Tasmania, 1966), PhD (Biochemistry, Flinders University of South Australia, 1969), Postdoctoral research fellow, Cornell University, New York (1969-1971), Queen Elizabeth II research fellow (Research School of Biological Sciences, Australian National University, 1971-1972), variously as a fulltime Lecturer to Reader (Associate Professor) (La Trobe University, 1972-2003), part-time lecturer (School of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 2004-2006, and at La Trobe University, 2007-2013). I have published about 100 scientific research papers, 19 chapters of books [1] and 3 substantial books, namely “Biochemical Targets of Plant Bioactive Compounds. A pharmacological reference guide to sites of action and biological effects” (2003) [1], “Jane Austen and the Black Hole of British History. Colonial rapacity, holocaust denial and the crisis in biological sustainability” (1998, 2008) [2], and “Body Count. Global avoidable mortality since 1950” (2007) [3]. I write and publish extensively overseas about the horrendous impact on Humanity and the Biosphere of violently-backed resource exploitation [1]. Growing up in Tasmania I was aware of the extraordinary beauty of the Tasmanian environment and after reading “Silent Spring” by Dr Rachel Carson [5] at the beginning of my zoological and chemical studies was horrified by the impact of chemical industry on animal life and became convinced that Man has no right to destroy any species, let alone complex ecosystems containing numerous plant, animal and microbial species. This view was reinforced by the likely extinction of the Tasmania tiger (Thylacinus cynocephalus) [6, 7], the biocidal pollution of the environs of Queenstown, and the drowning of numerous ecosystems by the Tasmanian Hydroelectric Commission (HEC). -

Reef Encounter

Volume 33, No. 1 September 2018 Number 46 REEF ENCOUNTER LIFE ACCOUNTS – Bob Ginsburg, Charlie Veron, Rod Salm, Wes Tunnell Society Honors, Prizes and Awards New Topic Chapter – The Coral Restoration Consortium CONFERENCES – Mexico, Florida Keys, Bremen, Oxford Graduate Fellowship Reports – corals, algae and fish The News Journal of the International Society for Reef Studies ISSN 0225-27987 REEF ENCOUNTER The News Journal of the International Society for Reef Studies ISRS Information REEF ENCOUNTER Reef Encounter is the Newsletter and Magazine Style Journal of the International Society for Reef Studies. It was first published in 1983. Following a short break in production it was re-launched in electronic (pdf) form. Contributions are welcome, especially from members. Please submit items directly to the relevant editor (see the back cover for author’s instructions). Coordinating Editor Rupert Ormond (email: [email protected]) Deputy Editor Caroline Rogers (email: [email protected]) Editors Reef Edge (Scientific Letters) Dennis Hubbard (email: [email protected]) Alastair Harborne (email: [email protected]) Edwin Hernandez-Delgado (email: [email protected]) Nicolas Pascal (email: [email protected]) Beatriz Casareto (Japan) (email: [email protected]) Editor Conservation and Obituaries Sue Wells (email: [email protected]) INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY FOR REEF STUDIES The International Society for Reef Studies was founded in 1980 at a meeting in Cambridge, UK. Its aim under the constitution is to promote, -

The Honolulu Declaration on Ocean Acidification and Reef Management

THE HONOLULU DECLARATION ON OCEAN ACIDIFICATION AND REEF MANAGEMENT Prepared and adopted by participants of the Ocean Acidification Workshop, convened by The Nature Conservancy, 12-14 August 2008, Hawaii Resilient Indo-Pacific coral reef. Copyright: Paul Marshall Background 0.1 units since the beginning of the Ocean acidification is the change in industrial revolution (Feely et al. 2004). ocean chemistry driven by the oceanic If current carbon dioxide emission uptake of chemical inputs to the trends continue, the ocean will continue atmosphere, including carbon, nitrogen to undergo acidification, to an extent and sulfur compounds (Doney et al. and at rates that have not occurred for 2007; Guinotte and Fabry 2008). The tens of millions of years. A doubling of ocean absorbs about one-third of the the concentration of atmospheric carbon carbon dioxide added to the atmosphere dioxide, which could occur in as little as by human activities each year (Sabine et 50 years, could cause major changes in al. 2004); and the pH of the ocean the marine environment, specifically surface waters has decreased by about impacting calcium carbonate organisms 1 (Orr et al. 2005). Such changes The growing threat of climate change compromise the long-term viability of combined with escalating anthropogenic coral reef ecosystems and the associated stressors on coral reefs requires a benefits that they provide. response that is both proactive and adaptive. To respond to this challenge, Coral reefs systems provide economic The Nature Conservancy convened a and environmental services to millions group of global ocean experts in of people as coastal protection from Honolulu, Hawaii from August 12-14, waves and storms, and as sources of 2008. -

Climate Change

theWIOMSAMAGAZINE people& the environment Issue no. 4 | June 2010 Buying time for corals Coal reef crisis Marine Protected Areas and climate change the WIOMSA magazine | no. 4 – Jun 2010 1 Conference on “Climate Change Impacts, Adaptation and Mitigation in the WIO region: Solutions to the Crisis” Grand Baie, Mauritius, 21-23 March 2011 THE FIRST gained in implementa- in the WIO region. be submitted to secretary@ ANNOUNCEMENT tion of adaptation and Priority will be given to wiomsa.org. AND CALL FOR mitigation strategies. summaries describing PAPERS e#orts undertaken by FINANCIAL ii) Support and facilitate governments, NGOs/ ASSISTANCE !e Western IndianCALL FOR WIOPAPERS countries in their CBOs and private sector A limited number of travel Ocean MarineSummaries Science are invitedquest on anyto forge topic a related com- to theto impacts address and implications adaptation to climategrants change will be provided Association (WIOMSA)in the WIO region. Prioritymon vision will beon given how to summariesof climate describing changes. efforts undertakento participants by from the in collaborationgovernments, with the NGOs/CBOsdeal with and implications private sector toSummaries address implications must be of climateregion changes. whose summaries Mauritius OceanographySummaries must be inof Englishclimate andchange. should not exceedin English 400 words. and should Submitted summaryhave been must accepted. Institute (MOI);FRQWDLQWKHIROORZLQJLQIRUPDWLRQWLWOHQDPH V RIDXWKRU V and not exceed 400DI¿OLDWLRQVSRVWDODQGHPDLO words. Applications for the the Nairobi Conventionaddresses. It shouldiii) alsoDevelop clearly a common state the preferredSubmitted mode of summarypresentation must (oral ortravel poster). grants should be Secretariat are 6XPPDU\PXVWEHLQ7LPHV1HZ5RPDQSRLQWIRQWVLQJOHVSDFLQJZLWKMXVWL¿HGDOLJQPHQWpleased to stand in priorities for contain the following accompanied by details announce the 6XPPDULHVVKRXOGEULHÀ\GHVFULEHWKHLUSURMHFWVLQLWLDWLYHVSUREOHPVWKH\DUHDGGUHVVLQJPDMRU"rst Confer- actions in relation to information: title, name(s) of the support required. -

GCRMN Climate Change

EVIDEN C E OF CLIMATE CHANGE DAMAGE TO CORAL REEFS CON C LUSIONS AND RE C OMMENDATIONS SCTATULIMATES OF C CARIBBEANHANGE • Mass coral bleaching was unknown in the long oral history CORAL REEF S Global climate change seriously threatens the immediate future of coral reefs: AND of many countries such as the Maldives and Palau, before AFTER BLEA C HING their reefs were devastated in 1998. About 16% of the world’s • Global climate change damage to coral reefs will threaten the livelihoods of 500 million people around the CORAL REEF S corals bleached and died in 1998; world and seriously reduce the $100 billion that reefs provide the global economy. AND HURRI C ANE S • In that year, 500 to 1000 year old corals died in Vietnam, in • Global climate change has already damaged many of the world’s coral reefs; more greenhouse gases in the IN 2005 the Indian Ocean and Western Pacific; atmosphere will exacerbate this and threaten mass extinctions on coral reefs, including deep cold water • Coral bleaching was only recorded as minor local incidents corals. Consequencesedited by before the first large-scale bleaching was observed in 1983. • About 19% of the world’s coral reefs have been effectively destroyed by human activities (over-fishing and Clive Wilkinson • The hottest years on record in the tropical oceans were in of inaction 1997/98, 2003, 2004 and 2005; the major bleaching years for destructive fishing, sediment and nutrient pollution, and habitat loss) as well as by climate change. and David Souter o Caribbean corals were in 1998 and 2005. -

43485 Veron Et Al 2015.Pdf

ORIGINAL RESEARCH ARTICLE published: 18 February 2015 MARINE SCIENCE doi: 10.3389/fmars.2014.00081 Overview of distribution patterns of zooxanthellate Scleractinia John Veron 1,2,3*, Mary Stafford-Smith 1, Lyndon DeVantier 1 and Emre Turak 1,4 1 Coral Reef Research, Townsville, QLD, Australia 2 Department of Marine and Tropical Biology, James Cook University, Townsville, QLD, Australia 3 Department of Earth Sciences, University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD, Australia 4 Australian Centre for Tropical Freshwater Research, James Cook University, Townsville, QLD, Australia Edited by: This publication is an overview of a detailed study of coral distribution, diversity and Thomas K. Frazer, University of affinities worldwide. The species distribution maps in www.coralsoftheworld.com are Florida, USA based on comprehensive global assessments of the world’s 150 coral ecoregions. Original Reviewed by: surveys by the authors cover 4941 sites in 85 ecoregions worldwide. These are combined Hector Reyes-Bonilla, Universidad Autonoma de Baja California Sur, with a thorough summation of all biogeographic, taxonomic and related literature as Mexico well as an extensive review of museum and photographic collections worldwide and Charles Sheppard, Warwick extensive inter-personal communications. Species occurrences in ecoregions are recorded University, UK as confirmed, strongly predicted, uncertain or absent. These data are used to present *Correspondence: global maps of diversity and affinity at species level. There are two templates of John Veron, Coral Reef Research, 10 Benalla Road, Oak Valley, Indo-Pacific diversity and affinity: one dominated by the Coral Triangle and one created by Townsville, QLD 4811, Australia poleward continental boundary currents. There is a high degree of uniformity within the e-mail: j.veron@ main body of the Coral Triangle; diversity and affinities both decrease in all directions. -

The Honolulu Declaration on Ocean Acidification and Reef Management

The Honolulu Declaration on Ocean Acidification and Reef Management ! ! Prepared and adopted by participants of the Ocean Acidification Workshop, convened by The Nature Conservancy, 12-14 August 2008, Hawaii 1 IUCN Global Marine Programme Founded in 1948, The World Conservation Union brings together States, government agencies and a diverse range of non-governmental organizations in a unique world partnership: over 1000 members in all, spread across some 140 countries. As a Union, IUCN seeks to influence, encourage and assist societies throughout the world to conserve the integrity and diversity of nature and to ensure that any use of natural resources is equitable and ecologically sustainable. The IUCN Global Marine Programme provides vital linkages for the Union and its members to all the IUCN activities that deal with marine issues, including projects and initiatives of the Regional offices and the 6 IUCN Commissions. The IUCN Global Marine Programme works on issues such as integrated coastal and marine management, fisheries, marine protected areas, large marine ecosystems, coral reefs, marine invasives and protection of high and deep seas. The Nature Conservancy The mission of The Nature Conservancy is to preserve the plants, animals and natural communities that represent the diversity of life on Earth by protecting the lands and waters they need to survive. The Conservancy launched the Global Marine Initiative in 2002 to protect and restore the most resilient examples of ocean and coastal ecosystems in ways that benefit marine life, local communities and economies. The Conservancy operates over 100 marine conservation projects in more than 21 countries and 22 U.S. -

Magazine of the Species Survival Commission 350 Or

CAN WE STOP Species THE EXTINCTION CRISIS? Magazine of the Species Survival Commission © J. Martin ISSUE 50 JANUARY – JULY 2009 350 or bust ... coral reefs and climate change The contribution of species to ecosystem services Specialist Group exchange The world’s most comprehensive information source on the global conservation status of plant and animal species. www.iucnredlist.org Species 50 Contents 1 Editorial 8 350 or bust… 12 The contribution of species to ecosystem services 14 Specialist Group Exchange 27 SSC Sub-Committee Update 28 Steering Committee Update 30 Species Programme Update 34 Publications Summary Species is the magazine of the IUCN Species Programme and the IUCN Species Survival Commission. Commission members, in addition to providing leadership for conservation efforts for specific plant and animal groups, contribute to technical and scientific counsel to biodiversity conservation projects throughout the world. They provide advice to governments, international conventions, and conservation organizations. Team Species Dena Cator, Julie Griffin, Lynne Labanne, Kathryn Pintus, and Rachel Roberts Layout www.naturebureau.co.uk Cover Lined Sweetlips (Plectorhinchus lineatus) and Two-Tone Wrasse (Thalassoma amblycephalum) in a coral reef (Acropora spp.) Credit: © Nazir Amin Opinions expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect official views of IUCN/SSC ISSN 1016-927x ©2009 IUCN—International Union for Conservation of Nature Email: [email protected] For address changes, notify: SSC Membership Species Programme, IUCN Rue Mauverney 28 CH-1196 Gland, Switzerland Phone: +44 22 999 0268 Fax: +44 22 999 0015 Email: [email protected] SSC members are encouraged to receive the SSC monthly electronic news bulletin. Please contact Team Species at [email protected] for more information. -

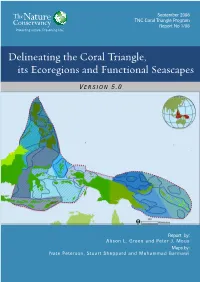

Delineating the Coral Triangle, Its Ecoregions and Functional Seascapes

September 2008 TNC Coral Triangle Program Report No 1/08 Delineating the Coral Triangle, its Ecoregions and Functional Seascapes V ERSION 5.0 Report by: Alison L. Green and Peter J. Mous Maps by: Nate Peterson, Stuart Sheppard and Muhammad Barmawi Published by: The Nature Conservancy, Coral Triangle Program Contact Details: Alison Green: The Nature Conservancy, 51 Edmondstone Street, South Brisbane. Qld. 4101. Australia. email: [email protected] Suggested Citation: Green A.L. & Mous P.J. 2008. Delineating the Coral Triangle, its Ecoregions and Functional Seascapes. Version 5.0. TNC Coral Triangle Program Report 1/08. 44 pp. © 2008, The Nature Conservancy All Rights Reserved. Reproduction for any purpose is prohibited without prior permission. Available from: Coral Triangle Center The Nature Conservancy Jl Pengembak 2 Sanur, Bali Indonesia Indo-Pacific Resource Centre The Nature Conservancy 51 Edmondstone Street South Brisbane, Queensland 4101 Australia Or via the worldwide web at: http://conserveonline.org/workspaces/tnccoraltriangle/ ii September 2008 TNC Coral Triangle Program Report No 1/08 Delineating the Coral Triangle, its Ecoregions and Functional Seascapes V ERSION 5.0 Report by: Alison L. Green and Peter J. Mous Maps by: Nate Peterson, Stuart Sheppard and Muhammad Barmawi iii Table of Contents 1 Executive Summary......................................................................................................... vii 2 Introduction ...................................................................................................................... -

WORLD HERITAGE RESEARCH: MAKING a DIFFERENCE CRC Reef: Research, Education & Capacity Building

WORLD HERITAGE RESEARCH: MAKING A DIFFERENCE CRC Reef: Research, Education & Capacity Building Simon Woodley, David McB Williams, Tim Harvey, Annabel Jones Research Centre World Heritage Research: Making a Difference CRC Reef: Research, Education and Capacity Building 1999-2006 Simon Woodley1 David McB Williams2 Tim Harvey3 Annabel Jones4 1 S&JWoodley Pty Ltd, 6 Kookaburra Place, Darlington WA 6070 2 AIMS, PMB 3, Townsville Qld 4810 3 CRC Reef Research Centre, PO Box 772, Townsville Qld 4810 4 James Cook University, Townsville Qld 4810 Research Centre Cooperative Research Centre for the Great Barrier Reef World Heritage Area. World Heritage Research: Making a Difference. CRC Reef Research, Education and Capacity Building 1999-2006. CRC Reef Research Centre. Townsville,Australia. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Bibliography. ISBN 1 876054 25 5 1. CRC Reef Research Centre. 2. Coral reef ecology - Research - Queensland - Great Barrier Reef. 3. Sustainable development - Research - Queensland - Great Barrier Reef. 4. Marine parks and reserves - Queensland - Great Barrier Reef - Management. 5. Great Barrier Reef (Qld.) - Research. I. Woodley, Simon John, 1944- . II. CRC Reef Research Centre. 577.7890709436 This publication should be cited as Woodley, S.J., Williams, D.McB., Harvey, T.,Jones, A. 2006. WorldHeritage Research: Making a Difference. CRC Reef Research, Education and Capacity Building 1999-2006. CRC Reef Research Centre. Townsville,Australia. This work is copyright. The Copyright Act 1968 permits fair dealing for study, research, news reporting, criticism or review. Although the use of the PDF format causes the whole work to be downloaded, any subsequent use is restricted to the reproduction of selected passages constituting less than 10% of the whole work, or individual tables or diagrams for the fair dealing purposes.