SAFETY in Time for Mosul JULY 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Extent and Geographic Distribution of Chronic Poverty in Iraq's Center

The extent and geographic distribution of chronic poverty in Iraq’s Center/South Region By : Tarek El-Guindi Hazem Al Mahdy John McHarris United Nations World Food Programme May 2003 Table of Contents Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................1 Background:.........................................................................................................................................3 What was being evaluated? .............................................................................................................3 Who were the key informants?........................................................................................................3 How were the interviews conducted?..............................................................................................3 Main Findings......................................................................................................................................4 The extent of chronic poverty..........................................................................................................4 The regional and geographic distribution of chronic poverty .........................................................5 How might baseline chronic poverty data support current Assessment and planning activities?...8 Baseline chronic poverty data and targeting assistance during the post-war period .......................9 Strengths and weaknesses of the analysis, and possible next steps:..............................................11 -

Iraq's Displacement Crisis

CEASEFIRE centre for civilian rights Lahib Higel Iraq’s Displacement Crisis: Security and protection © Ceasefire Centre for Civilian Rights and Minority Rights Group International March 2016 Cover photo: This report has been produced as part of the Ceasefire project, a multi-year pro- gramme supported by the European Union to implement a system of civilian-led An Iraqi boy watches as internally- displaced Iraq families return to their monitoring of human rights abuses in Iraq, focusing in particular on the rights of homes in the western Melhaniyeh vulnerable civilians including vulnerable women, internally-displaced persons (IDPs), neighbourhood of Baghdad in stateless persons, and ethnic or religious minorities, and to assess the feasibility of September 2008. Some 150 Shi’a and Sunni families returned after an extending civilian-led monitoring to other country situations. earlier wave of displacement some two years before when sectarian This report has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Union violence escalated and families fled and the Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada. The con- to neighbourhoods where their sect was in the majority. tents of this report are the sole responsibility of the publishers and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position of the European Union. © Ahmad Al-Rubaye /AFP / Getty Ceasefire Centre for Civilian Rights The Ceasefire Centre for Civilian Rights is a new initiative to develop ‘civilian-led monitoring’ of violations of international humanitarian law or human rights, to pursue legal and political accountability for those responsible for such violations, and to develop the practice of civilian rights. -

Iraq CRISIS Situation Report No. 49 (17 June – 23 June 2015)

Iraq CRISIS Situation Report No. 49 (17 June – 23 June 2015) This report is produced by OCHA Iraq in collaboration with humanitarian partners. It covers the period from 17 – 23 June. Due to the rapidly changing situation it is possible that the numbers and locations listed in this report may no longer be accurate. The next report will be issued on or around 3 July. Highlights More than 1,500 families return to Tikrit. Returnees need humanitarian assistance Close to 300,000 individuals displaced from Ramadi since 8 April NGOs respond to Sulaymaniyah checkpoint closures Concern over humanitarian conditions in Ameriyat al-Fallujah and Habbaniya Insufficient funding continues to limit humanitarian response capacity The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. Map created 25 June 2015. Situation Overview More than 1,500 families (approximately 9,000 individuals) returned to Tikrit City and surrounding areas between 14 and 23 June, after the area was retaken by Iraqi Security Forces in April, according to the Displacement Tracking Matrix (DTM) of the International Organization for Migration (IOM). Most of those who returned were Government civil servants who were requested to return. Approximately 80 per cent of Government employees have gone back to the area, local authorities report. Returnees reportedly were required to submit to ID checks, body and vehicle searches before being allowed through manned checkpoints. Authorities have reportedly dismantled 1,700 improvised explosive devices (IEDs) and cleared more than 200 booby-trapped houses. The recent returns brings the estimated total number of returnees in Tikrit District to 16,384 families (over 98,000 individuals), according to a partner NGO. -

Bidders' Conference

Bidders’ Conference Survey and Clearance in Ramadi, Iraq RFP Ref No: 88176_RFP_IRQ_Survey and Clearance in Ramadi, Iraq_16_33 Ground Brief-Iraq context Ramadi-UN Assessment March 2016 RFP Ref No: 88176_RFP_IRQ_Survey and Clearance in Ramadi, Iraq_16_33, Questions and Answer session Ground Brief-Iraq context Ramadi-UN Assessment March 2016 RFP Ref No: 88176_RFP_IRQ_Survey and Clearance in Ramadi, Iraq_16_33, Questions and Answer session Country Context: Iraq . 18 Governorates in Iraq of which: . 3 Governorates in Autonomous Kurdistan Region of Iraq . 1 Governorate and Capital in Baghdad . 63% Shia, 34% Sunni, 3% Other religions . Population estimated at 34M, of which: . Approx. 8M live in Baghdad . Approx. 8M live in Kurdistan Region . Approx. 3M live in Basrah . Approx. 1M live in Ramadi and districts . Approx. 2M live in Mosul (IS controlled ) . Estimates that at least 4 million Iraqis internally displaced National Boundaries and Key Cities: Baghdad Governorate: Capital: Baghdad Al Anbar Governorate: Capital: Ramadi Ground Brief-Iraq context Ramadi-UN Assessment March 2016 RFP Ref No: 88176_RFP_IRQ_Survey and Clearance in Ramadi, Iraq_16_33, Questions and Answer session : : : IEDs IEDs Unexploded Ordnance (UXO): Unexploded Ordnance (UXO): Project Challenges: Explosive Threats - Iraq faces the full spectrum of explosive threats including IEDs, UXO, ADW all of which are in Ramadi. Separate RFP for threat impact survey Security - history of ISIS and other armed groups (AQ, Shia and Sunni militia groups), Infrastructure – lack of water, -

UNITED NATIONS JOINT PROGRAMME DOCUMENT Response to Basra Water Crisis-Iraq

UNITED NATIONS JOINT PROGRAMME DOCUMENT Response to Basra water crisis-Iraq Country: Iraq Programme Title: Providing safe drinking water to Basra’s population-Iraq Joint Programme Outcome: By 2024, as many as 960,000 Basra residents have improved and sustainable access to safe water UNSDCF - Strategic Priority #4: Promoting Natural Resource and Disaster Risk Management, and Climate Change Resilience Programme Duration: 30 months Total estimated budget: $6,741,574 Anticipated start/end dates: Nov 2020 - Nov 2023 Fund Management Options(s): Pass-through Managing or Administrative Agent: UNICEF Sources of funded budget: • Donor: Netherlands Names and signatures of (sub) national counterparts and participating UN organizations UN National organizations coordinating bodies Hamida Ramadhani Yilmaz Al Najjar Signature Signature Name of Organization: UNICEF Authority: Ministry of Construction, Date & Seal Housing and Public Municipalities Date & Seal Zena Ali Ahmad Signature Name of Organization: UNDP Date & Seal UNITED NATIONS JOINT PROGRAMME DOCUMENT Response to Basra water Crisis-Iraq Table of Contents Title Page Table of Contents I 1. Executive Summary 1 2. Situation analysis 2 2.1 Water Scarcity in Basra 3 2.2 Responses to water scarcity in Basra 4 3. Strategies including lessons learned and the proposed joint programme 5 3.1 Project objective 5 3.2 Interventions Details 6 4. Results framework 9 5. Management and coordination arrangements 10 5.1 Joint Programme coordination 10 5.1.1 Joint Steering Committee 10 5.2 Joint Programme Management at Component Level 11 5.3 Technical Coordination and Convening Agent 12 5.4 Capability and capacity of partners 12 6. Fund Management 14 7. -

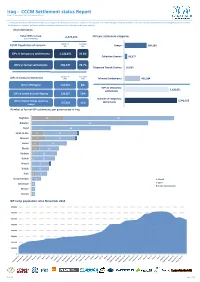

Iraq - CCCM Settlement Status Report from 13 December 2017 to 31 January 2018

Iraq - CCCM Settlement status Report From 13 December 2017 to 31 January 2018 This Report provides information on the various types of IDP locations in Iraq. CCCM area of response is the IDPs living in temporary Settlements, this report is about the formal category of them. Formal Settlements are camps, collective centres, reception/transit centres, & dispersed transit centres. Key Information Total IDPs in Iraq 2,470,974 IDPs per settlement categories (source DTM IOM) Number of % of total CCCM Population of concern IDPs IDPs Camps 580,193 IDPs in temporary settlements 1,130,821 45.8% Collective Centres 93,377 IDPs in formal settlements 709,237 28.7% Dispersed Transit Centres 35,667 Number of % of total IDPs in formal settlements IDPs IDPs Informal Settlements 421,584 IDPs in KRI Region 204,942 8% IDPs in temporary 1,130,821 settlements IDPs in Centre & South Regions 236,667 10% Outside of Temporary IDPs in Mosul Hawija response 1,340,153 267,628 11% Settlements camps Number of formal IDP settlements per governorate in Iraq Baghdad 16 56 Babylon 59 Najaf 40 Salah al-Din 6 17 1 Ninewa 7 15 1 Anbar 4 14 Diyala 4 10 Kerbala 13 Dahuk 1 11 Wassit 9 1 Kirkuk 9 Erbil 2 6 Sulaymaniyah 5 Closed Open Qadissiya 2 Under Construction Missan 2 Basrah 1 1 IDP camp population since November 2014 800,000 700,000 600,000 500,000 400,000 300,000 200,000 100,000 0 2/11/2018 Page 1 of 14 Iraq - CCCM Settlement status Report From 13 December 2017 to 31 January 2018 This Report provides information on the various types of IDP locations in Iraq. -

Unhcr Position on Returns to Iraq

14 November 2016 UNHCR POSITION ON RETURNS TO IRAQ Introduction ......................................................................................................................................................... 1 Violations and Abuses of International Human Rights and International Humanitarian Law .......................... 3 Treatment of Civilians Fleeing ISIS-Held Areas to Other Areas of Iraq ............................................................ 8 Treatment of Civilians in Areas Formerly under Control of ISIS ..................................................................... 11 Treatment of Civilians from Previously or Currently ISIS-Held Areas in Areas under Control of the Central Government or the KRG.................................................................................................................................... 12 Civilian Casualties ............................................................................................................................................ 16 Internal and External Displacement ................................................................................................................. 17 IDP Returns and Returns from Abroad ............................................................................................................. 18 Humanitarian Situation ..................................................................................................................................... 20 UNHCR Position on Returns ........................................................................................................................... -

Iraq, August 2006

Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Country Profile: Iraq, August 2006 COUNTRY PROFILE: IRAQ August 2006 COUNTRY Formal Name: Republic of Iraq (Al Jumhuriyah al Iraqiyah). Short Form: Iraq. Term for Citizen(s): Iraqi(s). Click to Enlarge Image Capital: Baghdad. Major Cities (in order of population size): Baghdad, Mosul (Al Mawsil), Basra (Al Basrah), Arbil (Irbil), Kirkuk, and Sulaymaniyah (As Sulaymaniyah). Independence: October 3, 1932, from the British administration established under a 1920 League of Nations mandate. Public Holidays: New Year’s Day (January 1) and the overthrow of Saddam Hussein (April 9) are celebrated on fixed dates, although the latter has lacked public support since its declaration by the interim government in 2003. The following Muslim religious holidays occur on variable dates according to the Islamic lunar calendar, which is 11 days shorter than the Gregorian calendar: Eid al Adha (Feast of the Sacrifice), Islamic New Year, Ashoura (the Shia observance of the martyrdom of Hussein), Mouloud (the birth of Muhammad), Leilat al Meiraj (the ascension of Muhammad), and Eid al Fitr (the end of Ramadan). Flag: The flag of Iraq consists of three equal horizontal bands of red (top), white, and black with three green, five-pointed stars centered in the white band. The phrase “Allahu Akbar” (“God Is Great”) also appears in Arabic script in the white band with the word Allahu to the left of the center star and the word Akbar to the right of that star. Click to Enlarge Image HISTORICAL BACKGROUND Early History: Contemporary Iraq occupies territory that historians regard as the site of the earliest civilizations of the Middle East. -

Iraq: Women Struggle to Make Ends Meet

January-February 2011 Iraq: Women struggle to make ends meet THE INTERNATIONAL COMMITTEE OF THE RED CROSS (ICRC) HAS BEEN WORKING IN IRAQ CONTINUOUSLY SINCE 1980 RESPONDING TO THE CONSEQUENCES OF ARMED CONFLICTS Overview A great many women in Iraq are facing challenges in the task of caring for their families, earning income and taking part in community and professional life. Since widespread violence erupted in 2003, they have been increasingly caught in the crossre, killed, wounded or driven from their homes. As their menfolk have been killed or taken way in large numbers, the entire burden of running the household has been suddenly thrust upon them. "Regardless of the circumstance of loss, the mere fact that there is no traditional breadwinner directly aects the family's nancial situation," says Caroline Douilliez, head of the ICRC's Women and War programme in Iraq. "The ICRC's observations across Iraq have led us to the distressing conclusion that the lack of regular and sucient income over the years has cast a huge number of families into severe poverty." According to ICRC estimates, between one and two million households in Iraq today are headed by women. This gure includes women whose husbands are either dead, missing (some since as far back as 1980) or detained. Divorced women are also taken into account. All these women were wives at one point in time, and today remain mothers to their children and daughters to their parents, and sometimes ultimately breadwinners and caregivers for all these people. Without a male relative, they lack economic, physical and social protection and support. -

Baghdad Governorate Profile May-August

Overview BAGHDAD GOVERNORATE PROFILE GOVERNORATE OF ORIGIN May-August 2015 1%10% Anbar Baghdad governorate is the most populous in the 9% Babylon 13,278 IDP individuals 8,286 IDP individuals Baghdad country, home to 7,145,470 individuals (excluding 4% 2% GENDER- AGE BREAKDOWN IDPs and Syrian refugees). By August it held over 2% Diyala 7% Ninewa 538,000 IDPs, the second largest concentration in 50,820 IDP individuals 654 IDP individuals 2% 67% Kirkuk Iraq. Over the past decade numerous waves of Salah al-Din 5-0 IDPs have come to this governorate, due to its 9% less than 1% 36,780 IDP individuals strategic location and the political importance of 7% 11-6 the country’s capital: as an example, Baghdad MOST COMMON SHELTER TYPE 39,882 IDP individuals ll IDP accommodated over a third of the estimated 1.6 f a s in o 18-12 7% ir % a million IDPs displaced in the aftermath of the 153,714 IDP individuals 7 q Samarra 2006 bombings. 29% Nabi Sheit 1 170,094 IDP individuals 49-19 Kadhra’a 15,108 IDP individuals ? Thawra 1 and 2, which constitute Sadr City, the 32% poorest suburb of Baghdad, used to be a strong- Al-Nabi Younis 3% +50 Al-Jamea;a Rented Host Families Unknown hold of religious militia that fought against housing 42% 49% shelter type 4% USA-led multi-national forces during their 0 INTENTIONS 8,000 intervention. Since start of the recent conflict in 2,000 4,000 6,000 10,000 12,000 14,000 late 2013, IDPs have continued to flow to Baghdad, settling mainly in Karkh, Abu Ghraib and Notably, 58% of all IDPs assessed in Baghdad were under Grand Total 1% 99% Mahmoudiya districts, situated near Ramadi and 18. -

Appendix A. Sample Design

APPENDIX A. SAMPLE DESIGN The sample for the Iraq Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey was designed to provide estimates on a large number of indicators on the situation of children and women at the national level; for areas of residence of Iraq represented by rural and urban (metropolitan and other urban) areas; for the 18 governorates of Iraq; and also for metropolitan, other urban, and rural areas for each governorate. Thus, in total, the sample consists of 56 different sampling domains, that includes 3 sampling domains in each of the 17 governorates outside the capital city Baghdad (namely, a “metropolitan area domain” representing the governorate city centre, an “other urban area domain” representing the urban area outside the governorate city centre, and a “rural area domain”) and 5 sampling domains in Baghdad (namely, 3 metropolitan areas representing “Sadir City”, “Resafa side”, and “Kurkh side”, an other urban area sampling domain representing the urban area outside the three Baghdad governorate city centres, and a sampling domain comprising the rural area of Baghdad). A multi-stage, stratified cluster sampling approach was used for the selection of the survey sample. Sample Size and Sample Allocation The adequate sample size ns for each of the 56 sampling domains, is 324 households. Thus, the target sample size for the Iraq MICS was calculated as 18144 households ( = 56 ns ). The following formula was used to estimate ns Z 2 ⋅ P (1 − P ) ⋅ deff 1−α n = 2 s E 2 where The required sample size for each sampling domains, n = s expressed as the number of households Z1- a /2 = z-value determined by the confidence level = 1.96 for 95% confidence limits deff = design effect = 2 p = The estimate of the proportion = 0.5 (assumed maximum) E = The total width of the expected confidence interval = 0.077 therefore, (1.96) 2 0.5(0.5)2 n = = 324 s (0.077 ) 2 Sample sizes and terms of error for all sampling domains, governorates, and total are shown in Table SD.1. -

Iraq- Baghdad Governorate, Resafa District (

( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( Iraq- Baghdad Governorate, Resafa District ( ( Tal Skhairy IQ-P08720 Turkey ( ( Ba'quba District Mosul! ! ) Erbil ﺑﻌﻘوﺑﺔ Sabe'a Diyala Governorate Syria Iran ( Qusor - 368 IQ-D058 Baghdad ! دﯾﺎﻟﻰ IQ-P08359 ( Ramadi !\ IQ-G10 ( Jordan Najaf! ( Qaryat Qal`at `Abd Al-Nahriyah Amar Bin Basrah! al Jasadi IQ-P12554 Yasir Village ( IQ-P08346 ( IQ-P08934 Arab Yahudah ( ( ( SaudiI QA-Pra11b9i0a5 Kuwait Al Sha'ab ( Al Sha'ab - 375 B Mojam' Al Baladrooz District (Mahala 351) IQ-P08281 IQ-P08282 ( Zahra - 329 ( ( ( IQ-P08338 ﺑﻠدروز ) Al Sha'ab Al Hamediya Hay Al - 339 Ur - 327 ( ( Aqari IQ-P08280 IQ-P08367 - 575 Al Hamediya IQ-D057 Basateen - ( Al Sha'ab IQ-P09077 - 575 IQ-P08964 ( ( Mahalla 348 Al Basaten Al ( - 331 IQ-P09078 Ma'amil - IQ-P08303 sadren complex IQ-P08278 Mahalla 799 ( ( IQ-P08998 IQ-P08237 Hay Ur ( ( ( IQ-P08983 Basaten - 362 Hay Al Al Wafa IQ-P08304 Tujjar Al Sha'ab complex - 333 Sector - Qaryat Um IQ-P08325 Al Rihlat illegal Mujamma' Al Sadir 8 - Al Bisatein IQ-P08291 5 Ma'amel Al-Ubaid Basateen ( Hay Adan ( - 333 ( Sharekah - 345 collective sector 74 Thawra (9) IQ-P09019 IQ-P08715 IQ-P08302 IQ-P08862( IQ-P08963 ( IQ-P08279 IQ-P08341 Thawra1 District ( ( ( IQ-P08274 IQ-P09090 IQ-P09075 ( ( Nazl Salman Hay Al Tujjar( ( Hay Al Sihaa Al Sha'ab ( ( ( ( ( ( Sadir 8 - اﻟﺛورة Afandi IQ-P08968 ( IQ-P08323 caravans complex 1 IQ-P08344 ( IQ-P08283 Sector 80 Tunis - 326 ( ( Tunis - 330 Hay Al Aqari IQ-P09091 IQ-P08364 (Mahalla 337) ( IQ-D046 IQ-P08365 ( Mujamma' Al Sadir 7 - IQ-P08316 Al Biydha'a Sheblah