Moral Vision in the Drama of Thomas Otway

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John Dryden and the Late 17Th Century Dramatic Experience Lecture 16 (C) by Asher Ashkar Gohar 1 Credit Hr

JOHN DRYDEN AND THE LATE 17TH CENTURY DRAMATIC EXPERIENCE LECTURE 16 (C) BY ASHER ASHKAR GOHAR 1 CREDIT HR. JOHN DRYDEN (1631 – 1700) HIS LIFE: John Dryden was an English poet, literary critic, translator, and playwright who was made England's first Poet Laureate in 1668. He is seen as dominating the literary life of Restoration England to such a point that the period came to be known in literary circles as the “Age of Dryden”. The son of a country gentleman, Dryden grew up in the country. When he was 11 years old the Civil War broke out. Both his father’s and mother’s families sided with Parliament against the king, but Dryden’s own sympathies in his youth are unknown. About 1644 Dryden was admitted to Westminster School, where he received a predominantly classical education under the celebrated Richard Busby. His easy and lifelong familiarity with classical literature begun at Westminster later resulted in idiomatic English translations. In 1650 he entered Trinity College, Cambridge, where he took his B.A. degree in 1654. What Dryden did between leaving the university in 1654 and the Restoration of Charles II in 1660 is not known with certainty. In 1659 his contribution to a memorial volume for Oliver Cromwell marked him as a poet worth watching. His “heroic stanzas” were mature, considered, sonorous, and sprinkled with those classical and scientific allusions that characterized his later verse. This kind of public poetry was always one of the things Dryden did best. On December 1, 1663, he married Elizabeth Howard, the youngest daughter of Thomas Howard, 1st earl of Berkshire. -

Spring 2008 Issue

www.diplomacyworld.net Variety Melange Variants: The Spice of Life Notes From the Editor Welcome back to another issue of Diplomacy World. that continues in the coming issues as well! This is now my fifth issue since returning as Lead Editor, and in some ways it was the hardest issue to do. I This issue you’ll also find the results of the latest believe this was simply a case of all the additional time Diplomacy World Writing Contest. While I would have and effort that went into doing Issue #100. It wasn’t until liked to get more entries than I did, at least we received #100 was finished and uploaded to the web site that I enough to actually award the prizes this time! realized how many extra hours I’d been spending each Congratulations to our winners, and keep your eyes week trying to assemble all that material. Sitting back open for future writing contests, or contests of other the next day, I was a bit worried about whether I had run types. If you have suggestions, please let me know. the well (or my personal gas tank) dry. Which leads me into the usual quarterly mantra: this Fortunately, that wasn’t the case. First of all, we had a particular issue, and Diplomacy World as a whole, is few wonderful pieces of material set aside for this issue, only as good as the articles you hobby members submit. starting with Stephen Agar’s variant symphony and I can’t write the whole thing myself, not even with the David McCrumb’s designer notes on 1499: The Italian assistance of the DW Staff…we need your ideas, your Wars. -

UNIT COUNTER POOL Both

11/23/2020 UNIT COUNTER POOL Home New Member Application Members Guide About Us Open Match Requests Unit Counter Pool AHIKS UNIT COUNTER POOL To request a lost counter, rulebook or accessory, email the UCP custodian, Brian Laskey at [email protected] ! Please Note: In order to use the Unit Counter Pool you must be a current member of AHIKS. If you are not a member but would like to find out how to join please go to the New Member Application page or click here!! AVALON HILL-VICTORY GAMES Across Five Aprils General 25-2 Counter Insert Advanced Civilization Bulge ‘81 Afrika Korps Empires in Arms Air Assault on Crete 1776 Anzio Tac Air ASL (Beyond Valor, Red Barricades, Yanks) B-17 General 26-3 Counter Insert Bismarck Flight Leader Blitzkreig Firepower Bitter Woods (1st ed. No Utility), 2nd ed Merchant of Venus Breakout Normandy Bulge ‘65 General 28-5 Counter Insert Bulge ’81 Midway/Guadalcanal Expansion Bulge ’91 Bull Run Caesar’s Legions Merchant of Venus Chancellorsville Panzer Armee Afrika Civil War Panzer Blitz Desert Storm (Gulf Strike: Desert Shield) Panzerkrieg D-Day Panzer Leader Devil’s Den Russian Campaign 1809 Siege of Jerusalem (Roman Only) Empires in Arms 1776 Firepower Stalingrad (Original) Flashpoint Golan Stalingrad (AHgeneral.org version) Flat Top (No Markers) Storm over Arnhem Fortress Europa Squad Leader France 1940 Submarine Gettysburg ‘77 Tactics II GI Anvil (German & SS Infantry; Small Third Reich file:///C:/Users/Owner/Desktop/UNIT COUNTER POOL.html 1/5 11/23/2020 UNIT COUNTER POOL Arms) Guadalcanal Tobruk Turning -

Ah-88Catalog-Alt

GAMES and PARTS PRICE LIST EFFECTIVE OCTOBER 26, 1988 ICHARGE' Ordering Information 2 ~®;: Role-Playlng Games 1~ 3 -M.-. Fantasy and Science Fiction Games I 3 .-I ff.i I . Mllltary Slmulatlons ~ 4 k-r.· \ .. 7 Strategy /Wargames I 5 (~[~i\l\ri The General Magazine I 7 tt1IJ. Miscellaneous Merchandise I ~ 8 ~-.....Leisure Tlme/Famlly Games I 8 ~ General Interest Games ~ 9 JC. Jigsaw Puzzles 9 ~XJ Sports Illustrated Games 1~9 Lh Discontinued Software micl"ocomputel" ~cmes 1 o Microcomputer Games micl"ocomputel" ~cmes 11 ~ Discontinued Parts List I 12 ~. How to Compute Shipping 16 Telephone Ordering/Customer Services 16 1989 AVALON HILL CHAMPIONSHIP CONVENTION •The national championships for numerous Avalon Hill games will be held sometime in 1989 somewhere in the Baltimore, MD region. If you would like to be kept informed of the games being offered in these national tournaments, send a stamped, self-addressed envelope to: AH Championships, 4517 Harford Rd., Baltimore, MD 21214. We will notify you of the time, place and games involved when details are finalized. For Credit Card Orders Call TOLL FREE 1·800·638·9292 Numbered circles represent wargame complexity rating on a scale of 1 to 10: 10 being the most complex. ---ROLE PLAYING GAMES THIS IS a complete listing of all current and discon HOW TO COMPUTE SHIPPING: tinued games and their parts listed in group classifica BILLAPPLELANE 10.00 See the last page of this booklet. RUNEOUEST-A Game of Action*, Imagination&VlLOI v.~~....~ ·: tions. Parts which are shaded do not come with the IN A RUSH? We can cut the red tape and handle your and Adventure SNAKEPIPE HOLLOW 10.00 (/!?!! game. -

Human Sacrifice and Seventeenth- Century Economics: Otway's Venice

id3316428 pdfMachine by Broadgun Software - a great PDF writer! - a great PDF creator! - http://www.pdfmachine.com http://www.broadgun.com HUMAN SACRIFICE AND SEVENTEENTH- CENTURY ECONOMICS: OTWAY’S VENICE PRESERV’D Derek Hughes University of Warwick Whereas human sacrifice in Virgil in inseparable from Aeneas’ mission, Tasso and his imitators repeatedly oppose Christian imperialism to the practice of human sacrifice, and see such imperialism as culminating in the abolition of cannibalistic sacrifice in the New World. The contrary view?? That European civilization itself embodied forms of sacrificial barbarity appears not only in the well-known condemnations of conquistador atrocities but, in England, in critical accounts of the growing culture of measurement, enumeration, and monetary exchange. Answering the contention that the East Indies trade did not justify the sacrifice of lives that it entailed, Dudley Digges responded by citing Neptune’s justification in the Aeneid of the sacrifice of Palinurusto the cause of empire: “unum pro multis [dabitur caput].” Not all authors were, however, so complacent. Particularly in the late seventeenth-century, authors such as Dryden, Otway, and Aphra Behn came to see the burgeoning trading economy as embodying systems of exchange which, in reducing the individual to an economic cipher, recreated the primal exchanges of human sacrifice. In Venice Preserv’d (1682), for example, Otway depicts an advanced, seventeenth-century trading empire, initially regulated by clocks, calendars, documents, and coinage. As the play proceeds, these are increasingly revealed to be elaborations of more primitive forms of exchange. A perpetually imminent regression to pre-social anarchy is staved off by what Otway portrays as the originary forms of economic transaction: the submissive offering of weapons to potential foes (daggers change hands far more often than coins) or the offering of the body in the act of human sacrifice. -

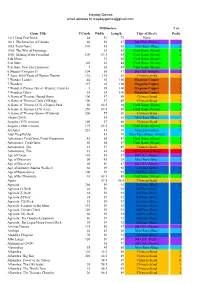

Mayday Games Email Updates to [email protected] # Of

Mayday Games email updates to [email protected] Millimeters # of Game Title # Cards Width Length Type of Sleeve Packs 1313 Dead End Drive 48 53 73 None 1812: The Invasion of Canada 60 56 87 Std USA (Purple) 1 1853 Train Game 110 45 68 Mini Euro (Blue) 2 1955: The War of Espionage 63 88 Card Game (Green) 0 1960: Making of the President 109 63.5 88 Card Game (Green) 2 2 de Mayo 63 88 Card Game (Green) 51st State 126 63 88 Card Game (Green) 2 51st State New Era Expansion 7 63 88 Card Game (Green) 1 6 Nimmt (Category 5) 104 56 87 Std USA (Purple) 2 7 Ages: 6000 Years of Human History 110 110 89 Chimera Sized 2 7 Wonder Leaders 42 65 100 Magnum Copper 1 7 Wonders 157 65 100 Magnum Copper 2 7 Wonders Promos (Stevie Wonder, Catan Island & Mannekin3 Pis) 65 100 Magnum Copper 1 7 Wonders Cities 38 65 100 Magnum Copper 1 A Game of Thrones -Board Game 100 57 89 Chimera Sized 1 A Game of Thrones Clash Of Kings 100 57 89 Chimera Sized 1 A Game of Thrones LCG -Chapter Pack 50 63.5 88 Card Game (Green) 1 A Game of Thrones LCG -Core 250 63.5 88 Card Game (Green) 3 A Game of Thrones Storm Of Swords 200 57 89 Chimera Sized 2 Abetto (2010) 45 68 Mini Euro (Blue) Acquire (1976 version) 180 57 88 Chimera Sized 2 Acquire (2008 version) 175 63.5 88 Card Game (Green) 2 Ad Astra 216 45 68 Mini Euro (Blue) 3 Adel Verpflichtet 45 70 Mini Euro (Blue) -Almost Adventurer Card Game Portal Expansion 45 64 89 Card Game (Green) 1 Adventurer: Card Game 80 64 89 Card Game (Green) 1 Adventurers, The 12 57 89 Chimera Sized 1 Adventurers, The 83 42 64 Mini Chimera (Red) -

Entire 2009-2010 Yearbook

2009 Team Tournament A record 104 teams vied for glory last year. Can you defy the Happy Handicapper’s odds to make the Top 25? 47-1 160-1 55-1 20-1 46-1 Dyer 4 • Johnson 9 Wixson 8 • Birnbaum 8 James 8 • Ro Beyma 7 Pei 7 • Dockter 3 Burdett 8 • Martin 2 Abrams 3 • McMaster 7 Drueding 0 • Rice 7 Ri Beyma 8 • Eliason 0 Byrd 7 • Mecay 3 Thompson 7 • Heidman 0 79-1 47-1 61-1 236-1 66-1 Levine 2 • A Field 11 Reese 8 • Maly 0 Rice 0 • Doane 2 Collinson 3 • Elliott 10 Gardner 2 • P Richardson 8 D Field 0 • Taillon 2 Young 0 • Edwards 7 Riekkinen 2 • Withers 10 Morgal 0 • Morgal 0 Nolan 0 • T Richardson 3 460-1 46-1 49-1 59-1 155-1 MacInnis 0 • Kaltman 2 Stein 0 • D Gutermuth 0 R Renaud 10 • Schmitt 0 Youells 8 • Kulp 0 Bove 10 • Hochboim 0 Castonguay 10 • Horan 0 Lisa G 9 • Ken G 2 Davis 0 • J Renaud 0 Cornett 2 • Galullo 0 Lehrer 0 • Warszawski 0 152-1 49-1 48-1 29-1 58-1 Moffa 0 • Flaxington 1 LaRose 0 • Sasseville 8 S Packwood 2 • Sam P 0 Applebaum 0 • Finberg 8 Hoam 0 • Wojtasczyk 7 Freeman 9 • Thatcher 0 Groulx 2 • Gagne 0 Backstrom 0 • Moyer 8 Fuegi 2 • Sample 0 Mullet 3 • Reiff 0 130-1 68-1 58-1 42-1 106-1 D Dolan 2 • Storzillo 8 Freeman 1 • G Dickson 2 Menzel 8 • Sharp 0 Latto 9 • Perry 0 Ed Beach 7 • Natalie B 0 T Dolan 0 • Gunar 0 Gregorio 7 • S Dickson 0 Wolff 0 • Thomson 2 S Brosius 0 • C Brosius 0 Matthew B 2 • Sara B 0 Contents 1 .8=&3=&884(.&9.43=4+='4&7),&2*=*39-:8.&898=.3(47547&9*)=&8=&=3438574Q9=(425&3>= =.3=9-*=89&9*=4+=4:9-=&741.3&=+47=9-*=*=57*88=5:7548*=4+=-489.3,=9-*=&33:&1=,&2.3,= (43+*7*3(*=034<3=&8=9-*=471)=4&7),&2.3,=-&25.438-.58`=47==+47=8-479_=9=4S*78=94:73&2*398`= -

The Heroic Tragedy

The Heroic Tragedy Heroic Tragedy is a name given to the form of tragedy which had some vogue in the beginning of the Restoration period (1660-1700). It was drama in the epic mode – grand, rhetorical and declamatory at its best and often bombastic at its worst. Its themes were love and honour, and it was considerably influenced by French classical drama, especially by the works of Corneille and Racine. John Dryden thus defined it in the preface to The Conquest of Granada (1672) : “ An heroic play ought to be an imitation, in little, of an heroic poem ; and consequently … love and valour ought to be the subject of it”. In these plays, as in an epic, the protagonist is a large-scale warrior whose actions involve the fate of an empire. A noble hero and an equally noble heroine are typically placed in a situation in which their passionate love is in conflict with the demands of honour and with the hero’s patriotic duty to his country. When the conflict ends in a disaster, the effect is a tragedy. Heroic drama was staged in a spectacular and operatic fashion, and in it one can detect the influences of opera which, at this time, was establishing itself. The two main early works of this genre were The Siege of Rhodes (1656) and The Spaniards in Peru (1658) by Sir William Davenant who was virtually the pioneer of English opera and who promoted heroic drama. The main plays thereafter were Robert Howard’s The Indian Queen (1665) and those by Dryden. -

Fall 2008 Issue

www.diplomacyworld.net Science Fiction and Fantasy in Diplomacy Notes from the Editor Welcome back to Diplomacy World, your hobby flagship columns to the sense of community and family so many since Walt Buchanan founded the zine in 1974! And, segments of the hobby had. Fiction, hilarious press, despite numerous near-death experiences, close calls, take-offs and send-ups, serious debate, triumph and financial insolvency, and predictions of doom, we’re still tragedy; they can all be found here, along with un- here, more than 100 issues later, bringing you the best obscured looks at the world as it changed over the last articles, hobby news, and opinions that we know how to 40+ years. I’m not sure how much I’ll be writing about produce. this project in future issues of Diplomacy World, but if nothing else it gave me the material for an article this Speaking of Diplomacy World’s past glories, this is as time, about the first real hobby scandal. If you’d like to good a place as any to mention that we have FINALLY read some of these zines, you can find them in the completed the task of scanning and posting every single Postal Diplomacy Zine Archive section at: issue of Diplomacy World ever produced. This includes every issue from #1 through #103 (the one you’re http://www.whiningkentpigs.com/DW/ reading now) plus the fake issue #40 and the full results of the Demo Game “Flapjack” which were never Incidentally, if you’d like to be kept up-to-date on what completely published. -

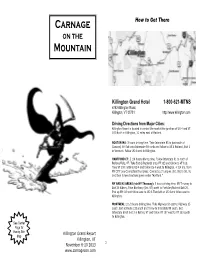

2013 Carnage Booklet 9-13

Carnage How to Get There on the Mountain Killington Grand Hotel 1 -800 -621 -MTNS 4763 Killington Road, Killington, VT 05751 http://www.killington.com Driving Directions from Major Cities: Killington Resort is located in central Vermont at the junction of US 4 and VT 100 North in Killington, 11 miles east of Rutland. BOSTON MA : 3 hours driving time. Take Interstate 93 to just south of Concord, NH Exit onto Interstate 89 north and follow to US 4 Rutland, Exit 1 in Vermont. Follow US 4 west to Killington. HARTFORD CT : 3 1/4 hours driving time. Follow Interstate 91 to north of Bellows Falls, VT. Take Exit 6 (Rutland) onto VT 103 and follow to VT 100. Take VT 100 north to US 4 and follow US 4 west to Killington. 4 3/4 hrs. from NY CITY (via Connecticut Turnpike): Connecticut Turnpike (Int. 95) to Int. 91 and then follow directions given under "Hartford." NY AND NJ AREAS (via NY Thruway): 5 hours driving time. NY Thruway to Exit 24 Albany. Take Northway (Int. 87) north to Fort Ann/Rutland Exit 20. Pick up NY 149 and follow east to US 4. Turn left on US 4 and follow east to Killington. MONTREAL: 3 1/2 hours driving time. Take Highway 10 east to Highway 35 south. Exit at Route 133 south and follow to Interstate 89 south. Exit Interstate 89 at Exit 3 in Bethel, VT and follow VT 107 west to VT 100 south to Killington. See Center Page for Handy Site Map Killington Grand Resort Killington, VT November 8-10 2013 2 www.carnagecon.com Welcome Join us in Killington, Vermont for the 16th annual Carnage convention, a celebration of tabletop gaming. -

Finding Aid to the Sid Sackson Collection, 1867-2003

Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play Sid Sackson Collection Finding Aid to the Sid Sackson Collection, 1867-2003 Summary Information Title: Sid Sackson collection Creator: Sid Sackson (primary) ID: 2016.sackson Date: 1867-2003 (inclusive); 1960-1995 (bulk) Extent: 36 linear feet Language: The materials in this collection are primarily in English. There are some instances of additional languages, including German, French, Dutch, Italian, and Spanish; these are denoted in the Contents List section of this finding aid. Abstract: The Sid Sackson collection is a compilation of diaries, correspondence, notes, game descriptions, and publications created or used by Sid Sackson during his lengthy career in the toy and game industry. The bulk of the materials are from between 1960 and 1995. Repository: Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play at The Strong One Manhattan Square Rochester, New York 14607 585.263.2700 [email protected] Administrative Information Conditions Governing Use: This collection is open to research use by staff of The Strong and by users of its library and archives. Intellectual property rights to the donated materials are held by the Sackson heirs or assignees. Anyone who would like to develop and publish a game using the ideas found in the papers should contact Ms. Dale Friedman (624 Birch Avenue, River Vale, New Jersey, 07675) for permission. Custodial History: The Strong received the Sid Sackson collection in three separate donations: the first (Object ID 106.604) from Dale Friedman, Sid Sackson’s daughter, in May 2006; the second (Object ID 106.1637) from the Association of Game and Puzzle Collectors (AGPC) in August 2006; and the third (Object ID 115.2647) from Phil and Dale Friedman in October 2015. -

Thesis Final Copy

Affect, Audience and Genre: Reading the Connection between the Restoration Playhouse and the Secret History by Erin M. Keating M.A., Concordia University, 2006 B.A., Wilfrid Laurier University, 1998 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of English Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences © Erin M. Keating 2012 Simon Fraser University Spring 2012 All rights reserved. However, in accordance with the Copyright Act of Canada, this work may be reproduced, without authorization, under the conditions for "Fair Dealing." Therefore, limited reproduction of this work for the purposes of private study, research, criticism, review and news reporting is likely to be in accordance with the law, particularly if cited appropriately. APPROVAL Name: Erin Keating Degree: Doctor of Philosophy Title of Thesis: Affect, Audience and Genre: Reading the Connection between the Restoration Playhouse and the Secret History Examining Committee: __________________________________________ Dr. Carolyn Lesjak Graduate Chair and Associate Professor of English __________________________________________ Dr. Betty Schellenberg Senior Supervisor Professor of English __________________________________________ Dr. Diana Solomon 2nd Reader Assistant Professor of English __________________________________________ Dr. Peter Dickinson 3rd Reader Professor of English __________________________________________ Dr. Lisa Shapiro Internal Examiner Chair and Associate Professor of Philosophy __________________________________________