Gaul.’ Felix Looked Around the Harbour As If He Expected – Or Even Hoped – to See Pirates Appear at Any Moment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

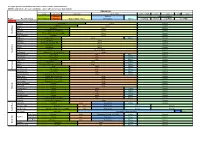

A Very Rough Guide to the Main DNA Sources of the Counties of The

A Very Rough Guide To the Main DNA Sources of the Counties of the British Isles (NB This only includes the major contributors - others will have had more limited input) TIMELINE (AD) ? - 43 43 - c410 c410 - 878 c878 - 1066 1066 -> c1086 1169 1283 -> c1289 1290 (limited) (limited) Normans (limited) Region Pre 1974 County Ancient Britons Romans Angles / Saxon / Jutes Norwegians Danes conq Engl inv Irel conq Wales Isle of Man ENGLAND Cornwall Dumnonii Saxon Norman Devon Dumnonii Saxon Norman Dorset Durotriges Saxon Norman Somerset Durotriges (S), Belgae (N) Saxon Norman South West South Wiltshire Belgae (S&W), Atrebates (N&E) Saxon Norman Gloucestershire Dobunni Saxon Norman Middlesex Catuvellauni Saxon Danes Norman Berkshire Atrebates Saxon Norman Hampshire Belgae (S), Atrebates (N) Saxon Norman Surrey Regnenses Saxon Norman Sussex Regnenses Saxon Norman Kent Canti Jute then Saxon Norman South East South Oxfordshire Dobunni (W), Catuvellauni (E) Angle Norman Buckinghamshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Bedfordshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Hertfordshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Essex Trinovantes Saxon Danes Norman Suffolk Trinovantes (S & mid), Iceni (N) Angle Danes Norman Norfolk Iceni Angle Danes Norman East Anglia East Cambridgeshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Huntingdonshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Northamptonshire Catuvellauni (S), Coritani (N) Angle Danes Norman Warwickshire Coritani (E), Cornovii (W) Angle Norman Worcestershire Dobunni (S), Cornovii (N) Angle Norman Herefordshire Dobunni (S), Cornovii -

The Mysterious World of Celtic Coins

The Mysterious World of Celtic Coins Coins were developed about 650 BC on the western coast of modern Turkey. From there, they quickly spread to the east and the west, and toward the end of the 5th century BC coins reached the Celtic tribes living in central Europe. Initially these tribes did not have much use for the new medium of exchange. They lived self-sufficient and produced everything needed for living themselves. The few things not producible on their homesteads were bartered with itinerant traders. The employ of money, especially of small change, is related to urban culture, where most of the inhabitants earn their living through trade or services. Only people not cultivating their own crop, grapes or flax, but buying bread at the bakery, wine at the tavern and garments at the dressmaker do need money. Because by means of money, work can directly be converted into goods or services. The Celts in central Europe presumably began using money in the course of the 4th century BC, and sometime during the 3rd century BC they started to mint their own coins. In the beginning the Celtic coins were mere imitations of Greek, later also of Roman coins. Soon, however, the Celts started to redesign the original motifs. The initial images were stylized and ornamentalized to such an extent, that the original coins are often hardly recognizable. 1 von 16 www.sunflower.ch Kingdom of Macedon, Alexander III the Great (336-323 BC) in the Name of Philip II, Stater, c. 324 BC, Colophon Denomination: Stater Mint Authority: King Alexander III of Macedon Mint: Colophon Year of Issue: -324 Weight (g): 8.6 Diameter (mm): 19.0 Material: Gold Owner: Sunflower Foundation Through decades of warfare, King Philip II had turned Macedon into the leading power of the Greek world. -

Caesar 54 Bc

CAESAR 54 BC INTRODUCTION Caesar 54BC, the fourth Campaign of Caesar in Gaul covers in fact the major invasion of the southern part of Britania (present-day England) by Julius Caesar. The Roman objective is to capture as many hostages as possible from the hostile local tribes. The Briton player must use all means at his disposal to prevent the suc- cess of the raid, to discourage further Roman invasions. Caesar 54BC lasts 14 turns, each of 2 weeks, between April and November 54 BC. The Romans, led by Caes- ar, are launching a campaign over the southern part of the island of Britania. • The Roman player must capture as fast as possible the stringholds of the opposing Briton tribes and take hostages from them, with the help of his famous general, his legions and his fleet. • His Briton opponent must prevent this, using his war chariots, coastal tribes and opportunities created by storms and bad weather hampering Roman supply. The game event cards allow full replay ability thanks to the numerous various situations that their create on the diplomatic, military, political or economical fields Average duration: 1h30 Favored side: none GAME DURATION Hardest side to play: none Caesar 54BC lasts 14 turns, each of 2 weeks, between April and November 54 BC. TheRoman player always moves first, followed by the Briton player. FORCES The Roman player controls the Roman (red), and possible (via Card) the Trinovantes (yellow) units. The Briton player controls the units of the various Briton tribes (Atrebates, Regnii, Catuvellaunii, Cantii, Begae, Incenii, Dobunii, all in variant of tan), as well as the Trinovantes (yellow) and the Menapii (light green). -

ARTHUR of CAMELOT and ATHTHE-DOMAROS of CAMULODUNUM: a STRATIGRAPHY-BASED EQUATION PROVIDING a NEW CHRONOLOGY for 1St MIILLENNIUM ENGLAND

1 Gunnar Heinsohn (15 June 2017) ARTHUR OF CAMELOT AND ATHTHE-DOMAROS OF CAMULODUNUM: A STRATIGRAPHY-BASED EQUATION PROVIDING A NEW CHRONOLOGY FOR 1st MIILLENNIUM ENGLAND “It seems probable that Camelot, Chrétien de Troyes’ [c. 1140-1190 AD] name for Arthur's Court, is derived directly from Camelod-unum, the name of Roman Colchester. The East Coast town was probably well-known to this French poet, though whether he knew of any specific associations with Arthur is unclear. […] John Morris [1973] suggests that Camulodunum might actually have been the High-King Arthur's Eastern Capital” (David Nash Ford 2000). "I think we can dispose of him [Arthur] quite briefly. He owes his place in our history books to a 'no smoke without fire' school of thought. [...] The fact of the matter is that there is no historical evidence about Arthur; we must reject him from our histories and, above all, from the titles of our books" (David N. Dumville 1977, 187 f.) I Why neither the habitats of Arthurian Celts nor the cities of their Saxon foes can be found in post-Roman Britain p. 2 II Contemporaneity of Saxons, Celts and Romans during the conquest of Britain in the Late Latène period of Aththe[Aθθe]-Domaros of Camulodunum/Colchester p. 14 III Summary p. 29 IV Bibliography p. 30 Author’s1 address p. 32 1 Thanks for editorial assistance go to Clark WHELTON (New York). 2 I Why neither the habitats of Arthurian Celts nor the cities of their Saxon foes can be found in post-Roman Britain “There is absolutely no justification for believing there to have been a historical figure of the fifth or sixth century named Arthur who is the basis for all later legends. -

'J.E. Lloyd and His Intellectual Legacy: the Roman Conquest and Its Consequences Reconsidered' : Emyr W. Williams

J.E. Lloyd and his intellectual legacy: the Roman conquest and its consequences reconsidered,1 by E.W. Williams In an earlier article,2 the adequacy of J.E.Lloyd’s analysis of the territories ascribed to the pre-Roman tribes of Wales was considered. It was concluded that his concept of pre- Roman tribal boundaries contained major flaws. A significantly different map of those tribal territories was then presented. Lloyd’s analysis of the course and consequences of the Roman conquest of Wales was also revisited. He viewed Wales as having been conquered but remaining largely as a militarised zone throughout the Roman period. From the 1920s, Lloyd's analysis was taken up and elaborated by Welsh archaeology, then at an early stage of its development. It led to Nash-Williams’s concept of Wales as ‘a great defensive quadrilateral’ centred on the legionary fortresses at Chester and Caerleon. During recent decades whilst Nash-Williams’s perspective has been abandoned by Welsh archaeology, it has been absorbed in an elaborated form into the narrative of Welsh history. As a consequence, whilst Welsh history still sustains a version of Lloyd’s original thesis, the archaeological community is moving in the opposite direction. Present day archaeology regards the subjugation of Wales as having been completed by 78 A.D., with the conquest laying the foundations for a subsequent process of assimilation of the native population into Roman society. By the middle of the 2nd century A.D., that development provided the basis for a major demilitarisation of Wales. My aim in this article is to cast further light on the course of the Roman conquest of Wales and the subsequent process of assimilating the native population into Roman civil society. -

Celtic Britain

1 arfg Fitam ©0 © © © © ©©© © © © © © © 00 « G XT © 8 i imiL ii II I IWtv,-.,, iM » © © © © © ©H HWIW© llk< © © J.Rhjsffi..H. © I EARLY BRITAIN, CELTIC BRITAIN. BY J. RHYS, M.A., D.Litt. (Oxon/). Honorary LL.D. (Edin.). Honorary D.Litt. (Wales). FROFESSOR OF CELTIC IN THE UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD J PRINCIPAL OF JESUS COLLEGE, AND LATE FELLOW OF MERTON COLLEGE FELLOW OF THE BRITISH ACADEMY. WITH TWO MAPS, AND WOODCUTS OF COIliS, FOURTH EDITION. FUBLISHED UNDER THE D.RECTION OF THE GENERAL LITERATURE COMMITTEE. LONDON: SOCIETY FOR PROMOTING CHRISTIAN KNOWLEDGE, NORTHUMBERLAND AVENUE, W.C. ; 43, queen victoria street, e.c. \ Brighton: 129, north street. New York : EDWIN S. GORHAM. iqoP, HA 1^0 I "l C>9 |X)VE AND MALCOMSON, LIMITED, PRINTERS, 4 AND 5, DEAN STREET, HIGH HOLBORN, LONDON, W.C. PREFACE TO THE FIRST EDITION. These are the days of little books, and when the author was asked to add one to their number, he accepted the invitation with the jaunty simplicity of an inexperienced hand, thinking that it could not give him much trouble to expand or otherwise modify the account given of early Britain in larger works ; but closer acquaintance with them soon convinced him of the folly of such a plan— he had to study the subject for himself or leave it alone. In trying to do the former he probably read enough to have enabled him to write a larger work than this ; but he would be ashamed to confess how long it has occupied him. As a student of language, he is well aware that no severer judgment could be passed on his essay in writing history than that it should be found to be as bad as the etymologies made by historians are wont to be ; but so essential is the study of Celtic names to the elucidation of the early history of Britain that the risk is thought worth incurring. -

The Britons in Late Antiquity: Power, Identity And

THE BRITONS IN LATE ANTIQUITY: POWER, IDENTITY AND ETHNICITY EDWIN R. HUSTWIT Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Bangor University 2014 Summary This study focuses on the creation of both British ethnic or ‘national’ identity and Brittonic regional/dynastic identities in the Roman and early medieval periods. It is divided into two interrelated sections which deal with a broad range of textual and archaeological evidence. Its starting point is an examination of Roman views of the inhabitants of the island of Britain and how ethnographic images were created in order to define the population of Britain as 1 barbarians who required the civilising influence of imperial conquest. The discussion here seeks to elucidate, as far as possible, the extent to which the Britons were incorporated into the provincial framework and subsequently ordered and defined themselves as an imperial people. This first section culminates with discussion of Gildas’s De Excidio Britanniae. It seeks to illuminate how Gildas attempted to create a new identity for his contemporaries which, though to a certain extent based on the foundations of Roman-period Britishness, situated his gens uniquely amongst the peoples of late antique Europe as God’s familia. The second section of the thesis examines the creation of regional and dynastic identities and the emergence of kingship amongst the Britons in the late and immediately post-Roman periods. It is largely concerned to show how interaction with the Roman state played a key role in the creation of early kingships in northern and western Britain. The argument stresses that while there were claims of continuity in group identities in the late antique period, the socio-political units which emerged in the fifth and sixth centuries were new entities. -

Changes in Celtic Consumption: Roman Influence on Faunal-Based Diets of the Atrebates

CHANGES IN CELTIC CONSUMPTION: ROMAN INFLUENCE ON FAUNAL-BASED DIETS OF THE ATREBATES by Alexander Frey Submitted to the Faculty of The Archaeological Studies Program Department of Archaeology and Anthropology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts University of Wisconsin-La Crosse 2016 Copyright © 2016 by Alexander Frey All rights reserved ii CHANGES IN CELTIC CONSUMPTION: ROMAN INFLUENCE ON FAUNAL DIETS OF THE ATREBATES Alexander Frey, B.A. University of Wisconsin-La Crosse, 2016 This study addresses cultural impacts of the Roman Empire on the British Celtic group, the Atrebates. The Atrebates held large portions of land in southern Britain, and upon Roman invasion in A.D. 43, became a client kingdom of the Roman Empire. With Roman rule also came Roman animal husbandry and consumption habits, reflected in archaeological faunal remains. To better understand this dietary transition, 23 faunal datasets were analyzed from within and around the capital city of Calleva Atrebatum, spanning from the pre-Roman Britain Iron Age to the post-Roman Saxon Age. In the analysis, published Number of Individual Specimens (NISP) and Minimum Number of Individuals (MNI) values were assessed to examine changes in the prominence of sheep, pigs, and cattle over time. This research demonstrates the pervasive impact of the Roman Empire on populations with whom they interacted, changing not only governing bodies, but also dietary practices. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to acknowledge the wonderful help and support from my friends and family during the process of writing this thesis. Special thanks to my readers, Dr. David A. -

Boudicca's Rebellion Against the Roman Empire in 60 AD Daniel Cohen Union College - Schenectady, NY

Union College Union | Digital Works Honors Theses Student Work 6-2016 Boudicca's Rebellion Against the Roman Empire in 60 AD Daniel Cohen Union College - Schenectady, NY Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, Celtic Studies Commons, European History Commons, and the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Cohen, Daniel, "Boudicca's Rebellion Against the Roman Empire in 60 AD" (2016). Honors Theses. 135. https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses/135 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Union | Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Union | Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i Boudicca’s Rebellion Against the Roman Empire in 60 AD By Daniel Cohen ********* Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Department of History UNION COLLEGE June, 2016 ii ABSTRACT Cohen, Daniel Boudicca’s Rebellion Against the Roman Empire in 60 AD This paper examines the rebellion of Boudicca, the queen of the Iceni tribe, during the Roman Empire’s occupation of Britannia in 60 AD. The study shows that had Boudicca not changed her winning strategy in one key battle, she could have forced the Roman Empire to withdraw their presence from Britannia, at least until it was prudent to invade again. This paper analyzes the few extant historical accounts available on Boudicca, namely those of the Roman historians Tacitus and Cassius Dio, to explore the effectiveness of tactics on both sides of the rebellion. -

The Trinovantian Staters of Dubnovellaunos

01 Kretz 1671 7/1/09 13:33 Page 1 THE TRINOVANTIAN STATERS OF DUBNOVELLAUNOS RAINER KRETZ Introduction IN contrast to other North Thames rulers, notably Cunobelinus and Tasciovanos, the gold coinage of the Trinovantian king Dubnovellaunos has to date received scant attention. Until recently, this may at least in part have been due to an insufficient number of coins being avail- able to facilitate a detailed study. At the time that Derek Allen published ‘Cunobelin’s gold’,1 just forty-one staters of Dubnovellaunos had been recorded, compared to the 159 of Cunobelinus forming the basis of Allen’s investigation. Since then, however, the growth of metal-detecting has seen a steady rise in the number of recorded Dubnovellaunos staters, and this study thus comprises a total of 113 coins. There may, however, be another factor at play in the lack of scholarly interest in Dubnovellaunos. To the casual observer all of his staters tend to look more or less identical, thereby seemingly offering little scope for original research. To this must be added the fact that due to their inherently simple design, many of the obverses are extremely difficult to identify and die-link, which makes any attempt at a detailed study a laborious and time consuming task. Coupled with Dubnovellaunos’s uncertain position within the North Thames hierarchy, and faced with the additional prospect of a Cantian dimension, this quite possibly persuaded most would-be researchers to concentrate on easier and ostensibly more rewarding subjects. This long overdue investigation has several aims. It will attempt to identify typologically and stylistically distinct phases within the development of Dubnovellaunos’s Trinovantian (or Essex) stater series and place these into approximate chronological order. -

The Romans in Britain

THE GREATNESS AND DECLINE OF THE CELTS CHAPTER II THE ROMANS IN BRITAIN I BRITAIN BEFORE ITS ROMANIZATION THE historians tell us that Comm, the chieftain of the Atrebates already mentioned, who was one of the most remarkable figures of the Gallic War, after serving Cæsar became a deadly enemy of Rome in consequence of a quarrel with an officer of the Roman army, who had betrayed him. In 51 he withdrew into Britain with some of his people, continuing the work of colonization done by the Belgæ in the south of the island. He struck coins with Latin characters. He had three sons, who reigned in Britain. [MacNeill, CCCCXLI, p. 168; Jullian, CCCXLVII, ii, p. 470.] Britain had not yet been conquered by Rome. Celtic civilization held its own there; Celtic art prevailed [Parkyn, CCCCXLVI, p. 101; Reginald A. Smith, "On Late Celtic Antiquities discovered at Welwyn," in CXXII; S. Reinach, in CXXXIX, 1925, 172. Cf. Collingwood, CCCCXX; Bushe Fox, Excavation of the Late-Celtic Urn-field at Swarling, Kent, CXXVI, 1925.]; ornament developed with taste, particularly enamel-work, with its combinations of colours. This art, indeed, quickly travelled far from the classic models of Celtic art; decorative fancy had free rein, while the workmanship continued to be admirable. The centre of this art, and of all the civilization of Britain, was in the south of England, in a region bounded on the north by a line drawn from the Bristol Channel to the Wash. Only here do we find Celtic coins. There were a few towns in Britain, open towns or oppida, such as Londinium (London), the port of the Cantii, Camulodunum (Colchester), the stronghold of the Trinovantes, Eboracum (York), the capital of the Brigantes. -

Vergil & Caesar Name of Assignment

Course Number (when applicable) Course Title AP Latin - Vergil & Caesar Name of Assignment (title of book(s), Author, Edition, and ISBN (when applicable) The Gallic War: Seven Commentaries (English), Carolyn Hammond ISBN 10: 199540268 Expectations/Instructions for Student When Completing Assignment Read the English of Caesar’s Gallic War Books 1, 6, and 7 (summaries of books 2-5 provided) and answer the questions in the attached reading packet (pdf). It might be helpful to answer the reading questions as you read through the text. reading questions (pdf) One Essential Question for Assignment What should we expect from comentarii in form and content - how does Caesar confirm and challenge these expectations? What point of view does Caesar take when describing actions? One Enduring Understanding for Assignment Caesar adapts the characters, structures, and tropes of historical prose to create a uniquely Roman commentary and define basic tenets of ‘Romanness’, as well as structure of Latin literature and language Parent Role and Expectations Students work independently. Estimated Time Requirement Approximately 1 week per English Book Questions for the English Reading of Julius Caesar’s Gallic Wars Answer questions in complete sentences. Book I 1. Outline each of the following territories in the colors indicated: Belgae (blue); Celts/ Gauls (yellow), Aquitani (red): Figure 1: The Roman Provinces in Gaul around 58 BC; note that the coastline shown here is the modern one, different from the ancient coastline in some parts of the English Channel 2. Who was Orgetorix and what were his ambitions? 3. Why did Orgetotix commit suicide? 4. What actions or preparations did the Helvetii make before leaving their homeland? 5.