The Trinovantian Staters of Dubnovellaunos

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

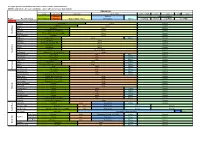

A Very Rough Guide to the Main DNA Sources of the Counties of The

A Very Rough Guide To the Main DNA Sources of the Counties of the British Isles (NB This only includes the major contributors - others will have had more limited input) TIMELINE (AD) ? - 43 43 - c410 c410 - 878 c878 - 1066 1066 -> c1086 1169 1283 -> c1289 1290 (limited) (limited) Normans (limited) Region Pre 1974 County Ancient Britons Romans Angles / Saxon / Jutes Norwegians Danes conq Engl inv Irel conq Wales Isle of Man ENGLAND Cornwall Dumnonii Saxon Norman Devon Dumnonii Saxon Norman Dorset Durotriges Saxon Norman Somerset Durotriges (S), Belgae (N) Saxon Norman South West South Wiltshire Belgae (S&W), Atrebates (N&E) Saxon Norman Gloucestershire Dobunni Saxon Norman Middlesex Catuvellauni Saxon Danes Norman Berkshire Atrebates Saxon Norman Hampshire Belgae (S), Atrebates (N) Saxon Norman Surrey Regnenses Saxon Norman Sussex Regnenses Saxon Norman Kent Canti Jute then Saxon Norman South East South Oxfordshire Dobunni (W), Catuvellauni (E) Angle Norman Buckinghamshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Bedfordshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Hertfordshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Essex Trinovantes Saxon Danes Norman Suffolk Trinovantes (S & mid), Iceni (N) Angle Danes Norman Norfolk Iceni Angle Danes Norman East Anglia East Cambridgeshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Huntingdonshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Northamptonshire Catuvellauni (S), Coritani (N) Angle Danes Norman Warwickshire Coritani (E), Cornovii (W) Angle Norman Worcestershire Dobunni (S), Cornovii (N) Angle Norman Herefordshire Dobunni (S), Cornovii -

Caratacus Errata

Caratacus Module Errata & Clarifications February, 2008 Components Counters There are 60 counters provided with the module. Corrections and additions to the counters include: •• The Briton MI should be BI instead •• Togudumnus counter is missing. Use any TC from Caesar/Gaul substituting the following ratings: Order/Line Range is 4/7; Initiative is 4; Charisma is 2 •• Cnaeus Sentius (commander of the Batavians) should have the following ratings: Command Range is 3; Initiative is 3; Line Command is 1; Charisma is 1; Strategy is 6. He is not a Cavalry commander, but the leader of the Batavians. The Briton army contains the following units: •• 2 Overall Commanders (Caratacus and Togodumnus) •• 3 Subordinate commanders (Taximagulus, Cingetorix, and Segovax chiefs of the Trinovantes, Atrebates and Cantii, respectively) •• 30 LI with 30 CH •• 20 BI (the MI counters) •• 4 LC Not all of the counters included in the module are used in the battles. There are 8 extra Briton BI (masquerading as MI, to be sure). Please use only 20 of these (you could always use the extras to alter play balance. Better more than too few). There is an extra Briton LI and CH, although including them is not exactly going to alter the game to any great extent. The extra CH counters are used for the extra Brit LI, which always used chariots to get around town. Since the original publication of the module, GMT has added 40 counters. This set includes: •• 20 Briton BI to replace the 20 Briton MI from the original counter set •• Togodumnus •• Cn. Sentius (ignore the Cav designation on the counter) •• 4 Batavian MI and 2 Batavian LI •• 12 Testudo/Harass & Disperse Markers Applicable Errata for Caesar: Conquest of Gaul Ignore this section when using the Caesar: Conquest of Gaul 2nd Edition rules. -

The Mysterious World of Celtic Coins

The Mysterious World of Celtic Coins Coins were developed about 650 BC on the western coast of modern Turkey. From there, they quickly spread to the east and the west, and toward the end of the 5th century BC coins reached the Celtic tribes living in central Europe. Initially these tribes did not have much use for the new medium of exchange. They lived self-sufficient and produced everything needed for living themselves. The few things not producible on their homesteads were bartered with itinerant traders. The employ of money, especially of small change, is related to urban culture, where most of the inhabitants earn their living through trade or services. Only people not cultivating their own crop, grapes or flax, but buying bread at the bakery, wine at the tavern and garments at the dressmaker do need money. Because by means of money, work can directly be converted into goods or services. The Celts in central Europe presumably began using money in the course of the 4th century BC, and sometime during the 3rd century BC they started to mint their own coins. In the beginning the Celtic coins were mere imitations of Greek, later also of Roman coins. Soon, however, the Celts started to redesign the original motifs. The initial images were stylized and ornamentalized to such an extent, that the original coins are often hardly recognizable. 1 von 16 www.sunflower.ch Kingdom of Macedon, Alexander III the Great (336-323 BC) in the Name of Philip II, Stater, c. 324 BC, Colophon Denomination: Stater Mint Authority: King Alexander III of Macedon Mint: Colophon Year of Issue: -324 Weight (g): 8.6 Diameter (mm): 19.0 Material: Gold Owner: Sunflower Foundation Through decades of warfare, King Philip II had turned Macedon into the leading power of the Greek world. -

Caesar 54 Bc

CAESAR 54 BC INTRODUCTION Caesar 54BC, the fourth Campaign of Caesar in Gaul covers in fact the major invasion of the southern part of Britania (present-day England) by Julius Caesar. The Roman objective is to capture as many hostages as possible from the hostile local tribes. The Briton player must use all means at his disposal to prevent the suc- cess of the raid, to discourage further Roman invasions. Caesar 54BC lasts 14 turns, each of 2 weeks, between April and November 54 BC. The Romans, led by Caes- ar, are launching a campaign over the southern part of the island of Britania. • The Roman player must capture as fast as possible the stringholds of the opposing Briton tribes and take hostages from them, with the help of his famous general, his legions and his fleet. • His Briton opponent must prevent this, using his war chariots, coastal tribes and opportunities created by storms and bad weather hampering Roman supply. The game event cards allow full replay ability thanks to the numerous various situations that their create on the diplomatic, military, political or economical fields Average duration: 1h30 Favored side: none GAME DURATION Hardest side to play: none Caesar 54BC lasts 14 turns, each of 2 weeks, between April and November 54 BC. TheRoman player always moves first, followed by the Briton player. FORCES The Roman player controls the Roman (red), and possible (via Card) the Trinovantes (yellow) units. The Briton player controls the units of the various Briton tribes (Atrebates, Regnii, Catuvellaunii, Cantii, Begae, Incenii, Dobunii, all in variant of tan), as well as the Trinovantes (yellow) and the Menapii (light green). -

ARTHUR of CAMELOT and ATHTHE-DOMAROS of CAMULODUNUM: a STRATIGRAPHY-BASED EQUATION PROVIDING a NEW CHRONOLOGY for 1St MIILLENNIUM ENGLAND

1 Gunnar Heinsohn (15 June 2017) ARTHUR OF CAMELOT AND ATHTHE-DOMAROS OF CAMULODUNUM: A STRATIGRAPHY-BASED EQUATION PROVIDING A NEW CHRONOLOGY FOR 1st MIILLENNIUM ENGLAND “It seems probable that Camelot, Chrétien de Troyes’ [c. 1140-1190 AD] name for Arthur's Court, is derived directly from Camelod-unum, the name of Roman Colchester. The East Coast town was probably well-known to this French poet, though whether he knew of any specific associations with Arthur is unclear. […] John Morris [1973] suggests that Camulodunum might actually have been the High-King Arthur's Eastern Capital” (David Nash Ford 2000). "I think we can dispose of him [Arthur] quite briefly. He owes his place in our history books to a 'no smoke without fire' school of thought. [...] The fact of the matter is that there is no historical evidence about Arthur; we must reject him from our histories and, above all, from the titles of our books" (David N. Dumville 1977, 187 f.) I Why neither the habitats of Arthurian Celts nor the cities of their Saxon foes can be found in post-Roman Britain p. 2 II Contemporaneity of Saxons, Celts and Romans during the conquest of Britain in the Late Latène period of Aththe[Aθθe]-Domaros of Camulodunum/Colchester p. 14 III Summary p. 29 IV Bibliography p. 30 Author’s1 address p. 32 1 Thanks for editorial assistance go to Clark WHELTON (New York). 2 I Why neither the habitats of Arthurian Celts nor the cities of their Saxon foes can be found in post-Roman Britain “There is absolutely no justification for believing there to have been a historical figure of the fifth or sixth century named Arthur who is the basis for all later legends. -

'J.E. Lloyd and His Intellectual Legacy: the Roman Conquest and Its Consequences Reconsidered' : Emyr W. Williams

J.E. Lloyd and his intellectual legacy: the Roman conquest and its consequences reconsidered,1 by E.W. Williams In an earlier article,2 the adequacy of J.E.Lloyd’s analysis of the territories ascribed to the pre-Roman tribes of Wales was considered. It was concluded that his concept of pre- Roman tribal boundaries contained major flaws. A significantly different map of those tribal territories was then presented. Lloyd’s analysis of the course and consequences of the Roman conquest of Wales was also revisited. He viewed Wales as having been conquered but remaining largely as a militarised zone throughout the Roman period. From the 1920s, Lloyd's analysis was taken up and elaborated by Welsh archaeology, then at an early stage of its development. It led to Nash-Williams’s concept of Wales as ‘a great defensive quadrilateral’ centred on the legionary fortresses at Chester and Caerleon. During recent decades whilst Nash-Williams’s perspective has been abandoned by Welsh archaeology, it has been absorbed in an elaborated form into the narrative of Welsh history. As a consequence, whilst Welsh history still sustains a version of Lloyd’s original thesis, the archaeological community is moving in the opposite direction. Present day archaeology regards the subjugation of Wales as having been completed by 78 A.D., with the conquest laying the foundations for a subsequent process of assimilation of the native population into Roman society. By the middle of the 2nd century A.D., that development provided the basis for a major demilitarisation of Wales. My aim in this article is to cast further light on the course of the Roman conquest of Wales and the subsequent process of assimilating the native population into Roman civil society. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses A study of the client kings in the early Roman period Everatt, J. D. How to cite: Everatt, J. D. (1972) A study of the client kings in the early Roman period, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/10140/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk .UNIVERSITY OF DURHAM Department of Classics .A STUDY OF THE CLIENT KINSS IN THE EARLY ROMAN EMPIRE J_. D. EVERATT M.A. Thesis, 1972. M.A. Thesis Abstract. J. D. Everatt, B.A. Hatfield College. A Study of the Client Kings in the early Roman Empire When the city-state of Rome began to exert her influence throughout the Mediterranean, the ruling classes developed friendships and alliances with the rulers of the various kingdoms with whom contact was made. -

Togodumnus ?= Togidubnus This Name (Or Names) Has Been Much Discussed, for Example Here

Togodumnus ?= Togidubnus This name (or names) has been much discussed, for example here. During the Roman conquest of Britain, according to Cassius Dio 60,20: ‘Plautius, accordingly, had a deal of trouble in searching them out; but when at last he did find them, he first defeated Caratacus and then Togodumnus, the sons of Cynobellinus, who was dead. (The Britons were not free and independent, but were divided into groups under various kings.) After the flight of these kings he gained by capitulation a part of the Bodunni, who were ruled by a tribe of the Catuellani; and leaving a garrison there, he advanced farther and came to a river.’ [Ὁ οὖν Πλαύτιος πολλὰ μὲν πράγματα ἀναζητῶν σφας ἔσχεν, ἐπεὶ δὲ εὗρέ ποτε (ἦσαν δὲ οὐκ αὐτόνομοι ἀλλ'ἄλλοι ἄλλοις βασιλεῦσι προστεταγμένοι), πρῶτον μὲν Καράτακον ἔπειτα Τογόδουμνον, Κυνοβελλίνου παῖδας, ἐνίκησεν· αὐτὸς γὰρ ἐτεθνήκει. Φυγόντων δὲ ἐκείνων προσεποιήσατο ὁμολογίᾳ μέρος τι τῶν Βοδούννων, ὧν ἐπῆρχον Κατουελλανοὶ ὄντες, κἀνταῦθα φρουρὰν καταλιπὼν πρόσω ᾔει.] The beginning of the next section is usually translated as ‘Shortly afterwards Togodumnus perished, but the Britons, so far from yielding, united all the more firmly to avenge his death. [Διά τε οὖν τοῦτο, καὶ ὅτι καὶ τοῦ Τογοδούμνου φθαρέντος οἱ Βρεττανοὶ οὐχ ὅσον ἐνέδοσαν, ἀλλὰ καὶ μᾶλλον πρὸς τὴν τιμωρίαν αὐτοῦ ἐπισυνέστησαν] These texts are unambiguous in stating that Τογοδουμνος was one of two sons of the late king Κυνοβελλινος, but to claim that he died (and how) may be over-interpretation. See below. In recounting the history of Roman Britain, Tacitus wrote (in Agricola 14): ‘Aulus Plautius was the first governor of consular rank, and Ostorius Scapula the next. -

Human Rights, Social Welfare, and Greek Philosophy Legitimate

Global Journal of HUMAN-SOCIAL SCIENCE: H Interdisciplinary Volume 15 Issue 8 Version 1.0 Year 2015 Type: Double Blind Peer Reviewed International Research Journal Publisher: Global Journals Inc. (USA) Online ISSN: 2249-460x & Print ISSN: 0975-587X Human Rights, Social Welfare, and Greek Philosophy Legitimate Reasons for the Invasion of Britain by Claudius By Tomoyo Takahashi University of California, United States Abstract- In 43 AD, the fourth emperor of Imperial Rome, Tiberius Claudius Drusus, organized his military and invaded Britain. The purpose of this paper is to investigate the legitimate reasons for The Invasion of Britain led by Claudius. Before the invasion, his had an unfortunate life. He was physically distorted, so no one gave him an official position. However, one day, something unimaginable happened. He found himself selected by the Praetorian Guard to be the new emperor of Roma. Many scholars generally agree Claudius was eager to overcome his physical disabilities and low expectations to secure his position as new Emperor in Rome by military success in Britain. Although his personal motivation was understandable, it was not sufficient enough for Imperial Rome to legitimize the invasion of Britain. It is important to separate personal reasons and official reasons. Keywords: (1) roman, (2) britain, (3) claudius, (4) roman emperor, (5) colonies, (6) slavery, (7) colchester, (8) veterans, (9) legitimacy. GJHSS-H Classification: FOR Code: 180114 HumanRightsSocialWelfareandGreekPhilosophyLegitimateReasonsfortheInvasionofBritainbyClaudius Strictly as per the compliance and regulations of: © 2015. Tomoyo Takahashi. This is a research/review paper, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution- Noncommercial 3.0 Unported License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/), permitting all non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. -

The Campaign of Aulus Plautius

Archaeological Journal ISSN: 0066-5983 (Print) 2373-2288 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/raij20 The Campaign of Aulus Plautius Edwin Guest LL.D. To cite this article: Edwin Guest LL.D. (1866) The Campaign of Aulus Plautius, Archaeological Journal, 23:1, 159-180, DOI: 10.1080/00665983.1866.10851344 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00665983.1866.10851344 Published online: 11 Jul 2014. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 1 View related articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=raij20 Download by: [University of California, San Diego] Date: 29 June 2016, At: 13:17 CAMPAIGN OF AULUS PLAUTIUS. CAMBORITVM Η(ύιιιώτ·ιώ/ι^ ^MV^ODVNVM 7 'GLEVVM; tpZUrn^&ldicstcr ^Aylesbury \VER0LAMl VN! \KSPAlbans fandiim Abinadom >VLL0NIAC£ MoiJafortL iiibiimjioiHiiotif LONDIN WaiiiuraCPwll' Thames ν— ί or,Forest \ή*όmines Teddawto'V VERLVCIO "2 Sum ihpltifonLj' ^XlGiujstoiv iRIWEi Fu.i'ojjibe Wood <Si Gcarg es HilL· '•'ppily Wood ilu'ltf Wood. (mUdJbrcL W Downloaded by [University of California, San Diego] at 13:17 29 June 2016 DorlaJig PORTVSfiVBs J Se-CCARVM PORTVS/LEFOTNIS Winchester FORTIFIED FORD. CowayStates. ^rcijaeoltrstcal Journal. SEPTEMBER, 1866. THE CAMPAIGN OF AULUS PLAUTIUS.1 By EDWIN GUEST, LL.D., Master of Gonvil and Caius College, Cambridge. BEFORE we can discuss with, advantage the campaign of Aulus Plautius in Britain, it will be necessary to settle, or at least endeavour to settle, certain vexed questions which have much troubled our English antiquaries. The first of these relates to the place where Caesar crossed the Thames. -

The Ancient Britons and the Roman Invasions 55BC-61AD

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. The Ancient Britons and the Roman Invasions 55BC- 61AD: An Analysis of Tribal Resistance and Response. Carl Meredith Bradley B.A. (Hum). December 2003. A thesis submitted towards the degree of Master of Arts of Massey U Diversity. ABSTRACT. The aim of this thesis is to analyse the response to the Roman invasions of 55BC to 61AD from the tribal groupings of southern Britain. Much has been written of the activities of the Roman commanders and soldiers, but this thesis looks to analyse this period of invasion from the position of the tribes of southern Britain. The opening chapters will provide a descriptive account of the land and people who occupied southern Britain and a survey of tribal response to the Roman invasions. The reasons behind the differing responses to Rome will be offered with an analysis of th~ tribal politics that existed in southern Britain between Caesar's invasions of 55-54BC and the Claudian invasion of 43AD. Three case studies consider the central response to the Roman incursions. The first looks at the resistance offered to Caesar by the British warlord Cassivellaunus. The second case study highlights the initial response to Rome in 43AD by Caratacus and his brother Togodumnus. Following the initial fighting to stop the Roman invasion, Caratacus moved westward to carry on resistance to Rome in Wales. -

Celtic Britain

1 arfg Fitam ©0 © © © © ©©© © © © © © © 00 « G XT © 8 i imiL ii II I IWtv,-.,, iM » © © © © © ©H HWIW© llk< © © J.Rhjsffi..H. © I EARLY BRITAIN, CELTIC BRITAIN. BY J. RHYS, M.A., D.Litt. (Oxon/). Honorary LL.D. (Edin.). Honorary D.Litt. (Wales). FROFESSOR OF CELTIC IN THE UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD J PRINCIPAL OF JESUS COLLEGE, AND LATE FELLOW OF MERTON COLLEGE FELLOW OF THE BRITISH ACADEMY. WITH TWO MAPS, AND WOODCUTS OF COIliS, FOURTH EDITION. FUBLISHED UNDER THE D.RECTION OF THE GENERAL LITERATURE COMMITTEE. LONDON: SOCIETY FOR PROMOTING CHRISTIAN KNOWLEDGE, NORTHUMBERLAND AVENUE, W.C. ; 43, queen victoria street, e.c. \ Brighton: 129, north street. New York : EDWIN S. GORHAM. iqoP, HA 1^0 I "l C>9 |X)VE AND MALCOMSON, LIMITED, PRINTERS, 4 AND 5, DEAN STREET, HIGH HOLBORN, LONDON, W.C. PREFACE TO THE FIRST EDITION. These are the days of little books, and when the author was asked to add one to their number, he accepted the invitation with the jaunty simplicity of an inexperienced hand, thinking that it could not give him much trouble to expand or otherwise modify the account given of early Britain in larger works ; but closer acquaintance with them soon convinced him of the folly of such a plan— he had to study the subject for himself or leave it alone. In trying to do the former he probably read enough to have enabled him to write a larger work than this ; but he would be ashamed to confess how long it has occupied him. As a student of language, he is well aware that no severer judgment could be passed on his essay in writing history than that it should be found to be as bad as the etymologies made by historians are wont to be ; but so essential is the study of Celtic names to the elucidation of the early history of Britain that the risk is thought worth incurring.