Australian Found-Footage Horror Film

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Just How Nasty Were the Video Nasties? Identifying Contributors of the Video Nasty Moral Panic

Stephen Gerard Doheny Just how nasty were the video nasties? Identifying contributors of the video nasty moral panic in the 1980s DIPLOMA THESIS submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Magister der Philosophie Programme: Teacher Training Programme Subject: English Subject: Geography and Economics Alpen-Adria-Universität Klagenfurt Evaluator Univ.-Prof. Dr. Jörg Helbig, M.A. Alpen-Adria-Universität Klagenfurt Institut für Anglistik und Amerikanistik Klagenfurt, May 2019 i Affidavit I hereby declare in lieu of an oath that - the submitted academic paper is entirely my own work and that no auxiliary materials have been used other than those indicated, - I have fully disclosed all assistance received from third parties during the process of writing the thesis, including any significant advice from supervisors, - any contents taken from the works of third parties or my own works that have been included either literally or in spirit have been appropriately marked and the respective source of the information has been clearly identified with precise bibliographical references (e.g. in footnotes), - to date, I have not submitted this paper to an examining authority either in Austria or abroad and that - when passing on copies of the academic thesis (e.g. in bound, printed or digital form), I will ensure that each copy is fully consistent with the submitted digital version. I understand that the digital version of the academic thesis submitted will be used for the purpose of conducting a plagiarism assessment. I am aware that a declaration contrary to the facts will have legal consequences. Stephen G. Doheny “m.p.” Köttmannsdorf: 1st May 2019 Dedication I I would like to dedicate this work to my wife and children, for their support and understanding over the last six years. -

Resavoring Cannibal Holocaust As a Mockumentary

hobbs Back to Issue 7 "Eat it alive and swallow it whole!": Resavoring Cannibal Holocaust as a Mockumentary by Carolina Gabriela Jauregui ©2004 "The worst returns to laughter" Shakespeare, King Lear We all have an appetite for seeing, an appétit de l'oeuil as Lacan explains it: it is through our eyes that we ingest the Other, the world.1 And in this sense, what better way to introduce a film on anthropophagy, Ruggero Deodato's 1979 film, Cannibal Holocaust, than through the different ways it has been seen.2 It seems mankind has forever been obsessed with the need to understand the world through the eyes, with the need for visual evidence. From Thomas the Apostle, to Othello's "ocular proof," to our television "reality shows," as the saying goes: "Seeing is believing." We have redefined ourselves as Homo Videns: breathers, consumers, dependants, and creators of images. Truth, in our society, now hinges on the visual; it is mediated by images. Thus it is from the necessity for ocular proof that Cinéma Vérité, Direct Cinema, documentary filmmaking and the mockumentary or mock-documentary genre stem. It is within this tradition that the Italian production Cannibal Holocaust inserts itself, as a hybrid trans-genre film. To better understand this film, I will not only look at it as a traditional horror film, but also as a contemporary mockumentary satire that presents itself as "reality" and highlights the spectator’s eye/I’s primal appetite. In the manner of Peter Watkins' film Culloden, Deodato's film is intended to confuse the audience's -

Models of Time Travel

MODELS OF TIME TRAVEL A COMPARATIVE STUDY USING FILMS Guy Roland Micklethwait A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University July 2012 National Centre for the Public Awareness of Science ANU College of Physical and Mathematical Sciences APPENDIX I: FILMS REVIEWED Each of the following film reviews has been reduced to two pages. The first page of each of each review is objective; it includes factual information about the film and a synopsis not of the plot, but of how temporal phenomena were treated in the plot. The second page of the review is subjective; it includes the genre where I placed the film, my general comments and then a brief discussion about which model of time I felt was being used and why. It finishes with a diagrammatic representation of the timeline used in the film. Note that if a film has only one diagram, it is because the different journeys are using the same model of time in the same way. Sometimes several journeys are made. The present moment on any timeline is always taken at the start point of the first time travel journey, which is placed at the origin of the graph. The blue lines with arrows show where the time traveller’s trip began and ended. They can also be used to show how information is transmitted from one point on the timeline to another. When choosing a model of time for a particular film, I am not looking at what happened in the plot, but rather the type of timeline used in the film to describe the possible outcomes, as opposed to what happened. -

Expanded Mockuworlds. Mockumentary As a Transmedial Narrative Style 2015

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Cristina Formenti Expanded Mockuworlds. Mockumentary as a Transmedial Narrative Style 2015 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/16508 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Formenti, Cristina: Expanded Mockuworlds. Mockumentary as a Transmedial Narrative Style. In: IMAGE. Zeitschrift für interdisziplinäre Bildwissenschaft. Themenheft zu Heft 21, Jg. 11 (2015), Nr. 1, S. 63– 80. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/16508. Erstmalig hier erschienen / Initial publication here: http://www.gib.uni-tuebingen.de/image/ausgaben-3?function=fnArticle&showArticle=325 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Deposit-Lizenz (Keine This document is made available under a Deposit License (No Weiterverbreitung - keine Bearbeitung) zur Verfügung gestellt. Redistribution - no modifications). We grant a non-exclusive, Gewährt wird ein nicht exklusives, nicht übertragbares, non-transferable, individual, and limited right for using this persönliches und beschränktes Recht auf Nutzung dieses document. This document is solely intended for your personal, Dokuments. Dieses Dokument ist ausschließlich für non-commercial use. All copies of this documents must retain den persönlichen, nicht-kommerziellen Gebrauch bestimmt. all copyright information and other information regarding legal Auf sämtlichen Kopien dieses Dokuments müssen alle protection. You are not allowed to alter this document in any Urheberrechtshinweise und sonstigen Hinweise auf gesetzlichen way, to copy it for public or commercial purposes, to exhibit the Schutz beibehalten werden. Sie dürfen dieses Dokument document in public, to perform, distribute, or otherwise use the nicht in irgendeiner Weise abändern, noch dürfen Sie document in public. dieses Dokument für öffentliche oder kommerzielle Zwecke By using this particular document, you accept the conditions of vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, aufführen, vertreiben oder use stated above. -

Action Against Israel/ 19 Africa Open Latest/ 23

ACTION AGAINST ISRAEL/ 19 AFRICA OPEN LATEST/ 23 PAGE 15 News Views March 8 OPINION 16 • DURBAN POISON 17 • 2022 BID 18& • LETTERS 20 • SPORT 21 -28 2015 LIVE season of the show. Under the telekinetic LONG… control of an alien species, Kirk and Uhura are “forced” to kiss. NBC executives were reluctant to screen the shot and asked for alternative takes. Shatner and Nichols deliberately flubbed the IN OUR alternative takes, so the kiss stayed. Nichols says she was surprised that the flood of mail the show received after the episode was aired was all positive. A letter from a Southern viewer said: “I am totally opposed to the mixing of the MEMORY races. However, any time a red- blooded American boy like Captain Kirk gets a beautiful dame in his arms that looks like Uhura, he ain’t gonna fight it.” But the defining character was Leonard Nimoy, who undoubtedly that of Spock (Leonard Nimoy). Born of a human played the iconic half- mother with an alien father from the fictitious planet Vulcan, Spock First officer and science officer Spock (Leonard Nimoy). has green blood (from a copper human half- base), distinctive pointed ears, and We can is mildly telepathic when in alien first reflect now physical contact with others. on how The conflict between his cold many of calculating Vulcan heritage and officer of the his human emotions became a depictions of conduit for many of the humanist the Starship future technology lessons woven by the show creators portrayed in Star Trek are part into the script. -

Complicated Views: Mainstream Cinema's Representation of Non

University of Southampton Research Repository Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis and, where applicable, any accompanying data are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis and the accompanying data cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content of the thesis and accompanying research data (where applicable) must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder/s. When referring to this thesis and any accompanying data, full bibliographic details must be given, e.g. Thesis: Author (Year of Submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University Faculty or School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. Data: Author (Year) Title. URI [dataset] University of Southampton Faculty of Arts and Humanities Film Studies Complicated Views: Mainstream Cinema’s Representation of Non-Cinematic Audio/Visual Technologies after Television. DOI: by Eliot W. Blades Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2020 University of Southampton Abstract Faculty of Arts and Humanities Department of Film Studies Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Complicated Views: Mainstream Cinema’s Representation of Non-Cinematic Audio/Visual Technologies after Television. by Eliot W. Blades This thesis examines a number of mainstream fiction feature films which incorporate imagery from non-cinematic moving image technologies. The period examined ranges from the era of the widespread success of television (i.e. -

Bodies of Desire and Bodies in Distress

Bodies of Desire and Bodies in Distress Bodies of Desire and Bodies in Distress: The Golden Age of Italian Cult Cinema 1970-1985 By Xavier Mendik Bodies of Desire and Bodies in Distress: The Golden Age of Italian Cult Cinema 1970-1985, By Xavier Mendik This book first published 2015 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2015 by Xavier Mendik All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-5954-0, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-5954-7 This book is dedicated with much love to Caroline and Zena CONTENTS Acknowledgements .................................................................................... ix Foreword ................................................................................................... xii Enzo G. Castellari Introduction ................................................................................................ 1 Bodies of Desire and Bodies of Distress beyond the ‘Argento Effect’ Chapter One .............................................................................................. 21 “There is Something Wrong with that Scene”: The Return of the Repressed in 1970s Giallo Cinema Chapter Two ............................................................................................ -

Star Trek STAG NL 15

President; Janet Quarton, c/o Mr. Woodhouse, Sutton Hill' Farm, :Blandford, TIorset:i ; '" Secretary; :Beth Hallam, Flat 3, 36 Clapham Rd., :Bedford. Editor; Sheila Clark, 6 Craigmill Cottages, Strathmartine, by TIundee. Art Editor, Helen McCarthy, 96A, Fonthill Rd, Finsbury Park, London N4 3HT Honorary members; Gene Roddenberry, Jim TIoohan, George Takei. *****'************** .: Hello there; my namets :Beth Hallam, 11m the ffat' one that played the 'male ', that's right, the male Tellarite in the fashion show. As Janet told you in the last newsletter, I entered S~T.A.G. cbmini tt:ee 2S f general dogsbodyt. And haven't I lived up to that, ti tl e! L~ Elnyone wants anything done, particularly anything , unple8'sant 'or messy '- they saylphone':Beth, she'll do it!" Tt 1 s all 8 foul plot of She"ila Cl"a"rkl s! ... .; I ..... \ Well; I'sup"pDs-e. that' s what 11m for! Who ran off 100 'Zlnes in EI. fortnight? I tll gi V8 you. one guess; (I was .turning that handle 'in my sl;/,p'j ElDtJ. black ink seerri.s to get everywhere. Anyone',withe me'thod of'rEmoving it from inside a Swiss WEltch, please send in 'a plain envelope to .... !) Who took on's al'es,1 ? Right aga'in!' Who . is writing thi~ letter? ' ItWhy:n you. ask, Ilis writing EI letter to all you. nice people an unpleEls;)nt t1..lsk?11 Well, of course, it ±snlt, except that I have to , write abotl t a difflcul t subj ect - money! , , S.T.A .G. is a non-profi t-inaking organisation, but we must have an inc:>IDc. -

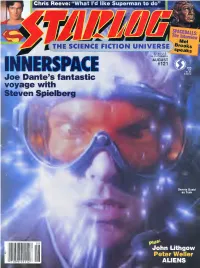

Starlog Magazine Issue

'ne Interview Mel 1 THE SCIENCE FICTION UNIVERSE Brooks UGUST INNERSPACE #121 Joe Dante's fantastic voyage with Steven Spielberg 08 John Lithgow Peter Weller '71896H9112 1 ALIENS -v> The Motion Picture GROUP, ! CANNON INC.*sra ,GOLAN-GLOBUS..K?mEDWARO R. PRESSMAN FILM CORPORATION .GARY G0D0ARO™ DOLPH LUNOGREN • PRANK fANGELLA MASTERS OF THE UNIVERSE the MOTION ORE ™»COURTENEY COX • JAMES TOIKAN • CHRISTINA PICKLES,* MEG FOSTERS V "SBILL CONTIgS JULIE WEISS Z ANNE V. COATES, ACE. SK RICHARD EDLUND7K WILLIAM STOUT SMNIA BAER B EDWARD R PRESSMAN»™,„ ELLIOT SCHICK -S DAVID ODEll^MENAHEM GOUNJfOMM GLOBUS^TGARY GOODARD *B«xw*H<*-*mm i;-* poiBYsriniol CANNON HJ I COMING TO EARTH THIS AUGUST AUGUST 1987 NUMBER 121 THE SCIENCE FICTION UNIVERSE Christopher Reeve—Page 37 beJohn Uthgow—Page 16 Galaxy Rangers—Page 65 MEL BROOKS SPACEBALLS: THE DIRECTOR The master of genre spoofs cant even give the "Star wars" saga an even break Karen Allen—Page 23 Peter weller—Page 45 14 DAVID CERROLD'S GENERATIONS A view from the bridge at those 37 CHRISTOPHER REEVE who serve behind "Star Trek: The THE MAN INSIDE Next Generation" "SUPERMAN IV" 16 ACTING! GENIUS! in this fourth film flight, the Man JOHN LITHGOW! of Steel regains his humanity Planet 10's favorite loony is 45 PETER WELLER just wild about "Harry & the CODENAME: ROBOCOP Hendersons" The "Buckaroo Banzai" star strikes 20 OF SHARKS & "STAR TREK" back as a cyborg centurion in search of heart "Corbomite Maneuver" & a "Colossus" director Joseph 50 TRIBUTE Sargent puts the bite on Remembering Ray Bolger, "Jaws: -

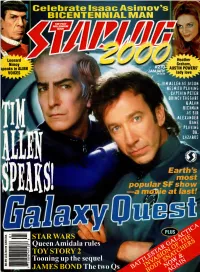

Starlog Magazine

Celebrate Isaac Asimov's BICENTENNIAL MAN 2 Leonard * V Heather Nimoy Graham, speaks in ALIEN — AUSTIN POWERS' VOICES lady love 1 40 (PIUS) £>v < -! STAR WARS CA J OO Queen Amidala rules o> O) CO TOY STORY 2 </) 3 O) Tooning up the sequel ft CD GO JAMES BOND The two Q THE TRUTH If you're a fantasy sci-fi fanatic, and if you're into toys, comics, collectibles, Manga and anime. if you love Star Wars, Star Trek, Buffy, Angel and the X-Files. Why aren't you here - WWW.ign.COtH mm INSIDE TOY STORY 2 The Pixarteam sends Buzz & Woody off on adventure GALAXY QUEST: THE FILM Questarians! That TV classic is finally a motion picture HEROES OF THE GALAXY Never surrender these pin- ups at the next Quest Con! METALLIC ATTRACTION Get to know Witlock, robot hero & Trouble Magnet ACCORDING TO TIM ALLEN He voices Buzz Lightyear & plays the Questarians' favorite commander THAT HEROIC GUY Brendan Fraser faces mum mies, monsters & monkeys QUEEN AMIDALA RULES Natalie Portman reigns against The Phantom Menace THE NEW JEDI ORDER Fantasist R.A. Salvatore chronicles the latest Star Wars MEMORABLE CHARACTER Now & Again, you've seen actor ! Cerrit Graham 76 THE SPY WHO SHAGS WELL Heather Graham updates readers STARLOC: The Science Fiction Universe is published monthly by STARLOG GROUP, INC., 475 Park Avenue South, New York, on her career moves NY 10016. STARLOG and The Science Fiction Universe are registered trademarks of Starlog Group Inc' (ISSN 0191-4626) (Canadian GST number: R-124704826) This is issue Number 270, January 2000. -

American International Pictures (AIP) Est Une Société De Production Et

American International Pictures (AIP) est une société de production et distribution américaine, fondée en 1956 depuis "American Releasing Corporation" (en 1955) par James H. Nicholson et Samuel Z. Arkoff, dédiée à la production de films indépendants à petits budgets, principalement à destination des adolescents des années 50, 60 et 70. 1 Né à Fort Dodge, Iowa à une famille juive russe, Arkoff a d'abord étudié pour être avocat. Il va s’associer avec James H. Nicholson et le producteur-réalisateur Roger Corman, avec lesquels il produira dix-huit films. Dans les années 1950, lui et Nicholson fondent l'American Releasing Corporation, qui deviendra plus tard plus connue sous le nom American International Pictures et qui produira plus de 125 films avant la disparition de l'entreprise dans les années 1980. Ces films étaient pour la plupart à faible budget, avec une production achevée en quelques jours. Arkoff est également crédité du début de genres cinématographiques, comme le Parti Beach et les films de motards, enfin sa société jouera un rôle important pour amener le film d'horreur à un niveau important avec Blacula, I Was a Teenage Werewolf et Le Chose à deux têtes. American International Pictures films engage très souvent de grands acteurs dans les rôles principaux, tels que Boris Karloff, Elsa Lanchester et Vincent Price, ainsi que des étoiles montantes qui, plus tard deviendront très connus comme Don Johnson, Nick Nolte, Diane Ladd, et Jack Nicholson. Un certain nombre d'acteurs rejetées ou 2 négligées par Hollywood dans les années 1960 et 1970, comme Bruce Dern et Dennis Hopper, trouvent du travail dans une ou plusieurs productions d’Arkoff. -

Why Found Footage Horror Films Matter : Introduction

Why Found Footage Horror Films Matter : Introduction Peter Turner, Oxford Brookes University The cinematic image of a young woman staring into the camera – crying, hyperventilating, and talking directly to her audience – has become the definitive image of The Blair Witch Project (Myrick and Sanchez, 1999). It is arguably the most famous scene, and certainly the most parodied image of found footage horror cinema in general, perhaps even one of the defining images of cinema in the 1990s. This character, Heather Donahue, is played by a hitherto unknown actress called Heather Donahue, in her feature debut. From what we see on screen, and the manner in which her monologue is delivered, it can be inferred that she is not reciting scripted lines. She does not seem to be acting; her fear appears genuine. Heather is alone in a dark tent, shooting this footage herself with a handheld camera. The shot did not look like most other horror films that had been previously shown in cinemas; it is poorly framed, poorly lit, and the character knows and acknowledges that she is on camera. There had been previous films in this style: Cannibal Holocaust (Deodato, 1980) contains the use of ‘found footage’ within its narrative structure, and Man Bites Dog (Belvaux, Bonzel and Poelvoorde, 1992) is a mock-documentary that purports to be completely filmed by a diegetic film crew. However, neither of these films had the cultural impact or box office success of The Blair Witch Project, a film that eventually spawned numerous imitators, and arguably the entire found footage horror sub- genre that now consists of hundreds of films.1 There is a straightforward economic reason why filmmakers continue to produce found footage horror films.