Mindfulness-Based Restoration Skills Training (Rest)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Admirable Trees of Through Two World Wars and Witnessed the Nation’S Greatest Dramas Versailles

Admirable trees estate of versailles estate With Patronage of maison rémy martin The history of France from tree to tree Established in 1724 and granted Royal Approval in 1738 by Louis XV, Trees have so many stories to tell, hidden away in their shadows. At Maison Rémy Martin shares with the Palace of Versailles an absolute Versailles, these stories combine into a veritable epic, considering respect of time, a spirit of openness and innovation, a willingness to that some of its trees have, from the tips of their leafy crowns, seen pass on its exceptional knowledge and respect for the environment the kings of France come and go, observed the Revolution, lived – all of which are values that connect it to the Admirable Trees of through two World Wars and witnessed the nation’s greatest dramas Versailles. and most joyous celebrations. Strolling from tree to tree is like walking through part of the history of France, encompassing the influence of Louis XIV, the experi- ments of Louis XV, the passion for hunting of Louis XVI, as well as the great maritime expeditions and the antics of Marie-Antoinette. It also calls to mind the unending renewal of these fragile giants, which can be toppled by a strong gust and need many years to grow back again. Pedunculate oak, Trianon forecourts; planted during the reign of Louis XIV, in 1668, this oak is the doyen of the trees on the Estate of Versailles 1 2 From the French-style gardens in front of the Palace to the English garden at Trianon, the Estate of Versailles is dotted with extraordi- nary trees. -

Current Issued Citrus Fruit Dealer Licenses

Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services Date: 01/20/2021 File: FVBLi0018 Division of Fruit and Vegetables Page: 1 Bartow, FL Season: 2020-2021 The following licenses have been issued for the 2020-2021 season as of 01/20/2021 License Bond Amount Number Name City 1 305 SQUEEZED, INC. Miami 0 95 ALBRITTON FRUIT COMPANY, INC. Sarasota 12,000 149 ALCARAZ, MARTHA Plant City 0 118 ALICO, INC. Arcadia 14,000 4 ALL AMERICAN JUICE MACHINES, LLC Miami 0 107 APCS, Inc Fort Pierce 13,000 96 ARDMORE FARMS, LLC Deland 0 217 Ace High Farms, LLC Fort Pierce 0 148 Ag Applications, LLC Winter Haven 22,000 2 Alex's Flamingo Groves, Inc Dania Beach 1,256 3 All American Citrus, Inc Miami 0 53 Ambassador Services, Inc Cape Canaveral 0 150 Ambrosia on the Square LLC The Villages 1,000 173 Arcadia Citrus Enterprises, Inc Fort Myers 50,000 5 B L Lanier Fruit Company, Inc Winter Haven 0 218 BOB ROTH'S NEW RIVER GROVES, INC Davie 1,000 56 BORDEN DAIRY OF FLORIDA, LLC Winter Haven 0 7 BREWER CITRUS Arcadia 100,000 54 Barajas Fruit, Inc Wauchula 20,000 119 Barben Fruit Company, Inc Avon Park 69,000 55 Ben Hill Griffin, Inc Frostproof 100,000 6 Bentley Brothers, Inc Winter Haven 100,000 112 Bob Paul, Inc Winter Haven 25,000 120 Bryan Paul Citrus, Inc Fort Denaud 5,000 166 Bublitz, Inc Lutz 1,000 105 Butrico Groves Mims 0 197 C J Fruit, Inc Polk City 14,000 113 C W H Harvesting, LLC Arcadia 70,000 121 C Young Citrus, Inc Eagle Lake 18,000 8 CAITO FOODS, LLC Lakeland 0 9 CHAPMAN FRUIT COMPANY, INC Wauchula 100,000 94 CITRUS WORLD, INC/FLORIDA'S NATURAL -

Fruit)From Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Jump To: Navigation, Search This Article Is About the Fruit

Orange (fruit)From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search This article is about the fruit. For the colour, see Orange (colour). For other uses, see Orange (disambiguation). "Orange trees" redirects here. For the painting by Gustave Caillebotte, see Les orangers. This article needs attention from an expert in botany. The specific problem is: Some information seems imprecise and some sources may be outdated. See the talk page for details. WikiProject Botany (or its Portal) may be able to help recrui t an expert. (November 2012) Orange Orange blossoms and oranges on tree Scientific classification Kingdom: Plantae (unranked): Angiosperms (unranked): Eudicots (unranked): Rosids Order: Sapindales Family: Rutaceae Genus: Citrus Species: C. × sinensis Binomial name Citrus × sinensis (L.) Osbeck[1] The orange (specifically, the sweet orange) is the fruit of the citrus species C itrus × ?sinensis in the family Rutaceae.[2] The fruit of the Citrus sinensis is c alled sweet orange to distinguish it from that of the Citrus aurantium, the bitt er orange. The orange is a hybrid, possibly between pomelo (Citrus maxima) and m andarin (Citrus reticulata), cultivated since ancient times.[3] Probably originating in Southeast Asia,[4] oranges were already cultivated in Ch ina as far back as 2500 BC. Arabo-phone peoples popularized sour citrus and oran ges in Europe;[5] Spaniards introduced the sweet orange to the American continen t in the mid-1500s. Orange trees are widely grown in tropical and subtropical climates for their swe et fruit, -

Orangeries & Conservatories

Glass & Windows Ltd ORANGERIES & CONSERVATORIES CONSERVATORY STYLES p4-5 CLASSIC ROOF FEATURES p6-9 INTERNAL & EXTERNAL OPTIONS p10-19 SOLID ROOFS p20-25 ORANGERIES p26-29 ULTRASKY & VERANDA p30-31 ABOUT US p32-36 Glass & Windows Ltd Your Local Home Improvement Company Since 1979 Be Inspired... Stratton Glass & Windows has been trading in Norfolk and Suffolk since 1979. In this time conservatories and orangeries have developed significantly. With solar control glazing, con- temporary features and solid tiled options; our range of conservatories & sun-rooms will help increase your living space whilst adding value to your home. With us you can rest assured that our skilled and enthusiastic team will design and install your dream conservatory or orangery to the highest standard. At Stratton Glass & Windows Ltd we are with you every step of the way from planning and design all the way through to installation and sign off. Our experienced team will manage your installation with great care and attention to detail. We are incredibly proud of our conservatory & orangery collection due to its vast versatility, durability, quality and style. We hope you like it too. Glass & Windows Ltd Conservatory Styles Gable Front Edwardian Victorian The front panel of the roof remains A flat-fronted style that offers excel- Its distinguishing upright for impressive high ceilings. lent use of floor space due to a architectural feature, a bay Just like an Edwardian it’s square square or rectangular internal front, with either an angled design provides optimal floor space. shape. (3 bay) or (5 bay) front. Lean-to Hybrid Orangery Loggia Provides a simplistic design whilst The Stratton “Hybrid Orangery” Our 21st century loggia design can achieving optimal space. -

Conservatories & Orangeries

CONSERVATORIES & ORANGERIES QUICK GUIDE TO OUR RANGE OF PRODUCTS 4 | CONSERVATORIES 22 | ORANGERIES 42 | LOGGIA 46 | SOLID ROOF EXTENSIONS 48 | REPLACEMENT 50 | DOOR STYLES Why choose CONSERVATORY OUTLET Deciding to invest in your home is CONTENTS X often a big decision; one that will involve many more choices on the 2 | PERSONALISED 50 | DOOR STYLES road to realising your dream home. DESIGN APPROACH Bi-Folding Doors By contacting your local Conservatory Outlet Dealer you’ve already made French Doors 4 | CONSERVATORIES one great choice. Patio Doors Classic Designs The Conservatory Outlet Network is a Contemporary Designs 58 | SPECIALIST SERVICE nationwide group of high calibre home improvement companies. Each regional Bespoke Designs Buying An Orangery or dealer is an expert in its field and staff Conservatory 22 | ORANGERIES pride themselves on local knowledge Frame Options Contemporary Designs and personal service, whilst benefiting Roof Options from the backing of national supply Traditional Designs Colours & Woodgrains partner, Conservatory Outlet. Bespoke Designs Finishing Touches Properties and personalities vary greatly, and all of our products are 46 | TAILOR MADE made-to-measure, so you won’t find an CONSERVATORIES off-the-shelf solution in this brochure. Loggia But what you will find is a fantastic Solid Roof Extensions array of genuine Conservatory Outlet Replacement Conservatories installations and design ideas which will help you make the most inspired and informed decision. Conservatory Outlet – A Quality Dealer Network 1 PERSONALISED DESIGN APPROACH Every conservatory and orangery is custom designed and manufactured to your exact requirements, so we believe that it is important that you are involved in every step of the design process. -

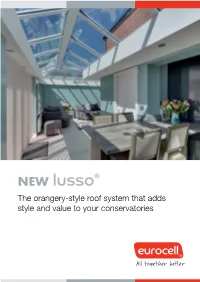

The Orangery-Style Roof System That Adds Style and Value to Your Conservatories Lusso®

NEW The orangery-style roof system that adds style and value to your conservatories lusso® STYLISH CONSERVATORIES WITH AN EXTRA TOUCH OF ELEGANCE ON TOP The orangery-style conservatory is the latest look for homeowners. With its traditional Victorian or Edwardian lines A modern take on traditional roof design and all that extra light, it’s easy to see why. With Lusso, you can create the look of an orangery. But without the extra building work or added cost of making But what if they want all the country house appeal of a genuine sure the conservatory can support a ‘fuller’ roof. orangery, but their budget won’t stretch to the real thing? That’s because Lusso looks like the real thing, right down to That’s easy. Offer them our Lusso conservatory roof. its deep perimeter, lantern roof and period details. But it’s a An internal pelmet and rooflight system that gives you lightweight, prefabricated system that’s quick and easy to install. everything you need to finish off their new conservatory, or refresh the look of an existing one, in true style. 2 | LUSSO SYSTEM GUIDE WHY CHOOSE A LUSSO CONSERVATORY ROOF? Easy to install Fast, accurate Low material and Better draft installation and labour costs proofing than construction conventional roofs Pitch range Cosy internal living More natural light 10-year 15-35 degrees environment than lantern roofs manufacturer product guarantee More sales opportunities Service and support Lusso lets you match your conservatories to a wider range Get expert advice from our Conservatory roofs of house styles with colour-matched trims and accessories, customer care team. -

2 the Orangery Elie House, Elie, Fife

2 THE ORANGERY ELIE HOUSE, ELIE, FIFE Outstanding Contemporary Home built in 2012, set in Beautiful Shared Parkland close to Elie 2 THE ORANGERY ELIE HOUSE, ELIE, FIFE, KY9 1EL Superb Contemporary Home Finished to a High Standard Rural Setting with Private Garden Beautiful Shared Parkland extending to almost 10 acres Situated about 0.7 Miles from Elie Beach and The Ship Inn Private Parking Distances St Andrews 14 miles, Edinburgh 44 miles Sitting Room, Kitchen, Dining Room, Landing with Family and Study Areas Principal Bedroom with En Suite Bathroom and Dressing Area 3 Further Bedrooms, Bathroom, Shower Room EPC = C Savills Edinburgh Wemyss House 8 Wemyss Place Edinburgh EH3 6DH 0131 247 3738 [email protected] savills.co.uk SITUATION 2 The Orangery, Elie House, is in a stunning parkland location within the estate walls of Elie House, on The dining area is open plan to the kitchen and sitting room, and has windows looking over the rear the edge of the pretty coastal village of Elie. The parkland setting offers walks to Kilconquhar Loch as garden and parkland beyond. French doors from the rear garden open into the sitting room and a well as providing picturesque surroundings to the house itself. corridor loops back round to the central hall. The sitting room has a stainless steel gas stove with tiled surround and LED lighting, and a feature wall with space for a flat screen television. Off the sitting room Elie is in the East Neuk of Fife, famed for its picturesque fishing villages and sandy beaches, with Elie are two storage cupboards, one of which houses the electronics for the house. -

J\V1ERICANI Iorticulturisf DECEMBER 1981

j\V1ERICANI IORTICULTURISf DECEMBER 1981 / lOmatoes in OCtober, November, and December? f course.. .and in January and February too with nutrients too. Your plants gradually absorb wnat they require Windowsill Gardens Nutriponics® Kits. If you simply and easily, eliminating the main causes of house O nave a sunny window you can grow tomatoes, plant failure; inadequate moisture and overwatering. peppers, geraniums, sunflowers, or whatever you wish in Nutriponics is a fully tested system. Over 65% of our our Gro-thru N Pots combined with our handsome planters customers reorder equipmemt and supplies, and kits are shown above. You can even grow your Nutriponic plants immediately available to get you started. Each includes our from seed. beautifully illustrated 50-page book on Nutriponics, to The lower container in this new system acts as a reservoir gether with Liqui-Soil, N Gro-thru Pots, and planting which enables the plant to take moisture as it needs it..and medium. Fill out the order coupon today. Windowsill Gardens, Grafton, N.H. 03240, Dept. AH D Senti Information Name, ___________~ =~_ D Send $4.95 kit Street'--______________ D Send $9.95 kit City State: _____Zip __ Include $2.00 for shipping WINDOWSILL GARDENS Grafton, New Hampshire 03240 #1ERICAN HORfICULTURIST DECEMBER 1981 FEATURES COLUMNS Camellias in Containers 16 Guest Editorial: Lessons We Can Learn Text and Photography by Anthony DeBlasi from Chelsea 2 A. St. Clair Wright Book Reviews 4 Gilbert S. Daniels Pronunciation Guide 8 Strange Relatives: The Cashew Family 9 Jane Steffey The Herb Garden: Thyme 13 Betty Ann Laws The Gotelli Dwarf Conifer Collection 20 Text by Steve Bender Photography by Barbara W. -

University of California, Riverside, Citrus Research Center and Agricultural Experiment Station Records

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8dj5d2h Online items available University of California, Riverside, Citrus Research Center and Agricultural Experiment Station records Finding aid prepared by History Associates Incorporated Special Collections & University Archives The UCR Library P.O. Box 5900 University of California Riverside, California 92517-5900 Phone: 951-827-3233 Fax: 951-827-4673 Email: [email protected] URL: http://library.ucr.edu/libraries/special-collections-university-archives © 2013 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. UA 042 1 Descriptive Summary Title: University of California, Riverside, Citrus Research Center and Agricultural Experiment Station records Date (inclusive): circa 1808-2007, undated. Date (bulk): 1910-1955 Collection Number: UA 042 Creator: University of California, Riverside. Citrus Research Center and Agricultural Experiment Station Extent: 63 linear feet(54 document boxes, 3 flat storage boxes, 8 glass plate negative boxes, 3 index card boxes, 1 lantern slide box, 2 map-case folders, unboxed material) Repository: Rivera Library. Special Collections Department. Riverside, CA 92517-5900 Abstract: The Citrus Research Center and Agricultural Experiment Station (CRC-AES) records collection contains administrative records, correspondence, faculty papers, publications, scrapbooks, clippings, photographs, reports, project files, and other material relating to CRC-AES. Formerly known as the Citrus Experiment Station (CES), the bulk of materials precede the establishment of UC Riverside's College of Letters and Sciences in 1954. The majority of topics document the history, events, faculty, staff, facilities, research, and experiments of CES. Materials related to CES research and experiments pertain to the physiology and morphology of citrus, fig, date palm, avocado, and other subtropical crops, soil management, smog studies, pest control, and diseases. -

The Kingdom of Flora to the Warsaw Society of Friends of Learning

The kingdom of fl ora Two-hundredth anniversary of the University’s Botanical Garden www.muzeum.uw.edu.pl University of Warsaw and it’s Botanical Garden n 1811, thanks to Stanisław Kostka Potocki, Chairman of the ICouncil of State, it was decided that the University of Warsaw – then in process of creation – it was to be located in the grounds of the former royal residence known as the Villa Regia or Kazi- mierzowski Palace, thus named after King Jan Kazimierz (1648- 68). Two hundred years ago, a Botanical Garden was created on the escarpment at the rear of the Palace; it was to be a type of herb garden and at the same time serve as a laboratory for the Medical School that had been established two years earlier. Al- though the Botanical Garden was removed to Aleje Ujazdows- kie in 1818, where it is still located today, the garden at the rear of the Kazimierzowski Palace, which was transformed fi rst into a vegetable garden and then a small park, was in use until the 1970s. This magical corner of Warsaw played an important role both in terms of the functioning of the Medical School, which soon became one of the faculties at the University of Warsaw, and in the lives of many of those who lived on the University’s grounds, including that of Fryderyk Chopin who mentions it in his lett ers which were writt en when he was a young man. In 2008 we celebrated the two-hundredth anniversary of the es- tablishment of the Law School, the fi rst faculty of the University. -

History of the United States Botanic Garden, 1816-1991

HISTORY OF THE UNITED STATES BOTANIC GARDEN 1816-1991 HISTORY OF THE UNITED STATES BOTANIC GARDEN 1816-1991 by Karen D. Solit PREPARED BY THE ARCHITECT OF THE CAPITOL UNDER THE DIRECTION OF THE JOINT COMMITTEE ON THE LIBRARY CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATES WASHINGTON 1993 For sale by the U.S. Government Printing Office Superintendent of Documents, Congressional Sales Office, Washington, DC 20402 ISBN 0-16-040904-7 0 • io-i r : 1 b-aisV/ FOREWORD The Joint Committee on the Library is pleased to publish the written history of our Nation's Botanic Garden based on a manuscript by Karen D. Solit. The idea of a National Botanic Garden began as a vision of our Nation's founding fathers. After considerable debate in Congress, President James Monroe signed a bill, on May 8, 1820, providing for the use of five acres of land for a Botanic Garden on the Mall. The History of the United States Botanic Garden, complete with illustrations, traces the origins of the U.S. Botanic Garden from its conception to the present. The Joint Committee on the Library wants to express its sincere appreciation to Ms. Solit for her extensive research and to Mr. Stephen W. Stathis, Analyst in American National Government with the Library of Congress 7 Congressional Research Service, for the additional research he provided to this project. Today, the United States Botanic Garden has one of the largest annual attendances of any Botanic Garden in the country. The special flower shows, presenting seasonal plants in beautifully designed displays, are enjoyed by all who visit our Nation's Botanic Garden. -

The Action of Yeast Strains As Biocontrol Agents Against Penicillium Digitatum in Lima Sweet Oranges

Article/Artigo Citrus Res. Technol., 41, e1054, 2020 ISSN 2236-3122 (Online) https://doi.org/10.4322/crt.18819 The action of yeast strains as biocontrol agents against Penicillium digitatum in Lima sweet oranges Tatiane da Cunha1, Luriany Pompeo Ferraz1, Gilmar da Silveira de Sousa-Júnior2 & Katia Cristina Kupper1,3 SUMMARY The green mold caused by Penicillium digitatum is the most important disease affecting citrus in the postharvest period. An alternative to control the disease lies on the use of yeasts. The purpose of the present study was to assess the ability of 101 yeasts strains to control P. digitatumin vitro and in vivo. The assay followed a randomized design with five repetitions and the evaluation took into consideration the mean pathogen colony diameter in Petri dish paired culture. In addition, the effect of the fungus on yeast strain growth was assessed. Orange fruits (Citrus sinensis cv. Lima) were injured in two equidistant points and inoculated with P. digitatum conidia suspension 24 hours before and after treatments, in the assays conducted in vivo. Treatments consisted in the application of eight yeast suspensions, fungicide and distilled water (control treatment); they followed a randomized design with three repetitions (20 fruits per repetition). The best antagonist results in vitro were recorded for five strains (Saccharomyces cerevisiae ACBL-76 and ACBL-82 strains; Candida stellimalicola ACBL-84 strain; and ACBL-87), which presented mycelial growth inhibition values higher than 80%. Two yeast strains (S. cerevisiae ACBL-82 strain and Meyerozyma caribbica ACBL-86 strain) have successfully controlled the progress and incidence of green mold in orange fruits when they were applied in a preventive manner.