Paper Money in Phnom Penh: Beyond the Sino-Khmer Tradition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heart to Heart Bound Together Forever

Volume 7 • Issue 1 February 2002 Heart to Heart Bound Together Forever FAMILIES WITH CHILDREN FROM CHINA – OREGON AND SW WASHINGTON The Gift of Language by Charlie Dolezal id you every have any regrets about your childhood? ber going to the FCC Saturday morning Mandarin classes. D Did you ever wish you had done something Hannah went for several months and never said a word. differently? Well, I do. I regret never having taken a foreign Then, one day in her car seat, she sang one of the songs. language. It wasn’t required. Language arts was not my best She was listening. She took it in. Children are like sponges. subject, so how could I excel at in another language? My We are fortunate here in Portland to have so many parents didn’t push me to take one. My dad always told language immersion programs, both public and private, to the story how his parents made the decision upon immigrating choose from. As FCC members we all have a tie to to America that their kids had to learn English to be a real Mandarin. We have elementary Mandarin programs at Americans and leave the “old” country behind. Thus, they never Woodstock (public school) and The International School taught my dad and his brothers and sisters their native tongue. (private school). In addition, there are immersion pro- When did I regret it? I regretted it on my first trip to Europe grams in French, German, Spanish, and Japanese to avail- with three college friends. We got a 48-hour visa to visit able in our community. -

An In-Depth Look at the Spiritual Lives of People Around the Globe

Faith in Real Life: An In-Depth Look at the Spiritual Lives of People around the Globe September 2011 Pamela Caudill Ovwigho, Ph.D. & Arnie Cole, Ed.D. Table of Contents Buddhists......................................................................................... 4 Faith Practices............................................................................... 5 Spiritual Me ................................................................................... 6 Life & Death .................................................................................. 6 Communicating with God............................................................... 7 Spiritual Growth ............................................................................ 7 Spiritual Needs & Struggles ........................................................... 8 Chinese Traditionalists ..................................................................... 9 Faith Practices............................................................................... 9 Life & Death ................................................................................ 10 Spiritual Me ................................................................................. 11 Communicating with God............................................................. 11 Spiritual Growth .......................................................................... 11 Spiritual Needs & Struggles ......................................................... 11 Hindus .......................................................................................... -

Khmer Civilization in Isan Khemita Visudharomn School of Architecture, Assumption University Bangkok, Thailand

AU J.T. 8(4): 178-184 (Apr. 2005) Khmer Civilization in Isan Khemita Visudharomn School of Architecture, Assumption University Bangkok, Thailand Abstract Follow the footsteps of Khmer civilization from Angkor Wat to the center of cultural heritage in northeastern Thailand, Phimai, Phanom Rung and Mueang Tam. This paper is both an introduction and guide to Khmer temples in Isan. The first part begins with historical details tracing the Angkorean from the 8th to 12th century, and introduces a background to the religious traditions of the Khmer, which both inspired and governed the concept and execution of all their art and architecture. The second part is an emphasis on architecture and decorative art, which appear in Khmer temples. In its heyday the main concentration of Khmer temples extended far west to the border and associated with an area of the middle Mekong River in the southern part of northeastern Thailand. Keywords: cultural heritage, Phimai, Phanom Rung, Mueang Tam, the Angkorean, religious traditions, architecture and decorative art 1. Introduction The other sources of information on this period are Chinese accounts and references, in The name “Isan” refers to the these to tributary states such as Funan and northeastern part of Thailand .It covers an area Chenla. of one third of the Kingdom. Isan, is also th th known as the Khorat Plateau. The Phetchabun 2.1 Angkorean (8 - 12 century) Rage separates Isan from the Central Region while the Dongrek Mountains in the south The art and architecture of the Khmer has separate Thailand from Cambodia. The Mun been classified into periods, by French art and Chi Rivers drain the majority of the historians. -

The Pioneer Chinese of Utah

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 1976 The Pioneer Chinese of Utah Don C. Conley Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Chinese Studies Commons, and the Mormon Studies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Conley, Don C., "The Pioneer Chinese of Utah" (1976). Theses and Dissertations. 4616. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/4616 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. THE PIONEER CHINESE OF UTAH A Thesis Presented to the Department of Asian Studies Brigham Young University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by Don C. Conley April 1976 This thesis, by Don C. Conley, is accepted in its present form by the Department of Asian Studies of Brigham Young University as satisfying the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts. Russell N. Hdriuchi, Department Chairman Typed by Sharon Bird ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author gratefully acknowledges the encourage ment, suggestions, and criticisms of Dr. Paul V. Hyer and Dr. Eugene E. Campbell. A special thanks is extended to the staffs of the American West Center at the University of Utah and the Utah Historical Society. Most of all, the writer thanks Angela, Jared and Joshua, whose sacrifice for this study have been at least equal to his own. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS iii INTRODUCTION 1 Chapter 1. -

A New Date for the Phnom Da Images and Its Implications for Early Cambodia

A New Date for the Phnom Da Images and Its Implications for Early Cambodia NANCY H. DOWLING SCHOLARS FAMILIAR WITH SOUTHEAST ASIAN ART HISTORY are well aware of a confusing chronology for early Cambodian sculpture. One reason for this situa tion is obvious. For nearly fifty years, Cambodian art history has been wed to the work of George Coedes. Praised as the dean of Southeast Asian history, he was a member of an elite group of French scholars who worked in Cambodia for decades before World War II. In 1944, he wrote Histoire ancienne des hats hindouses d'Extreme-Orient, in which he established a chronological framework for early Southeast Asian history based on an interplay of Chinese texts and indigenous inscriptions. Most Southeast Asian historians readily admit that "his book remains the basic source for early South East Asian history, and while much recent re search, based upon new inscriptional evidence or re-readings, modifies some of Coedes' specific conclusions, the structure remains his" (Brown 1996: 3). Such a singular dependency on Coedes had a stifling effect on Cambodian art history. When Jean Boisselier, carrying on the work of Philippe Stern and Gilberte de Coral-Remusat, made a comprehensive attempt to set in order Cambodian sculpture, the French art historian fitted the works of art into Coedes' ready made chronology. Unfortunately, this all happened as if it were preferable to adjust Cambodian sculpture to a preconceived notion of history rather than ques tioning the model. In this way, some basic mistakes have been made, and these seriously affect the chronology and interpretation of early Cambodian sculpture. -

The Russian Orthodox Church in Taiwan

Min-Chin Kay CHIANG LN “Reviving” the Russian Orthodox Church in Taiwan Abstract. As early as the first year into Japanese colonization (LcRd–LRQd), the Rus- sian Orthodox Church arrived in Taiwan. Japanese Orthodox Church members had actively called for establishing a church on this “new land”. In the post-WWII pe- riod after the Japanese left and with the impending Cold War, the Russian commu- nity in China migrating with the successive Kuomintang government brought their church life to Taiwan. Religious activities were practiced by both immigrants and local members until the LRcSs. In recent decades, recollection of memories was in- itiated by the “revived” Church; lobbying efforts have been made for erecting mon- uments in Taipei City as the commemorations of former gathering sites of the Church. The Church also continuously brings significant religious objects into Tai- wan to “reconnect” the land with the larger historical context and the church net- work while bonding local members through rituals and vibrant activities at the same time. With reference to the archival data of the Japanese Orthodox Church, postwar records, as well as interviews of key informants, this article intends to clarify the historical development and dynamics of forgetting and remembering the Russian Orthodox Church in Taiwan. Keywords. Russian Orthodox Church, Russia and Taiwan, Russian émigrés, Sites of Memory, Japanese Orthodox Church. Published in: Gotelind MÜLLER and Nikolay SAMOYLOV (eds.): Chinese Perceptions of Russia and the West. Changes, Continuities, and Contingencies during the Twentieth Cen- tury. Heidelberg: CrossAsia-eBooks, JSJS. DOI: https://doi.org/LS.LLdcc/xabooks.eeL. NcR Min-Chin Kay CHIANG An Orthodox church in the Traditional Taiwanese Market In winter JSLc, I walked into a traditional Taiwanese market in Taipei and surpris- ingly found a Russian Orthodox church at a corner of small alleys deep in the market. -

Results of the 1995-1996 Archaeological Field Investigations at Angkor Borei, Cambodia

Results of the 1995-1996 Archaeological Field Investigations at Angkor Borei, Cambodia JUDY LEDGERWOOD, MICHAEL DEGA, CAROL MORTLAND, NANCY DOWLING, JAMES M. BAYMAN, BONG SOVATH, TEA VAN, CHHAN CHAMROEUN, AND KYLE LATINIS ALTHOUGH ANCIENT STATES EMERGED in several parts of Southeast Asia (Bent ley 1986; Coedes 1968; Higham 1989a, 1989b), few of the world's archaeologists look to Southeast Asia to study the development of sociopolitical complexity. One reason for this lack of attention is that other Old \Xlodd regions, such as the N ear East, have dominated research on early civilizations (see also Morrison 1994). Perhaps another reason lies in archaeologists' current focus on prehistoric research: we have made great strides in understanding key changes in the pre history of Southeast Asia (see Bellwood 1997 and Higham 1989a, 1989b, 1996 for reviews). Our understanding of the archaeology of early state formation in main land Southeast Asia, however, has developed more slowly (Hutterer 1982). Many long-term research programs on this topic have been initiated only in the past decade (Allard 1994; Glover et al. 1996; Glover and Yamagata 1995; Higham 1998; Moore 1992, 1998; Yamagata and Glover 1994). Nowhere is this gap in our understanding more acute than in Cambodia, where one of the great ancient states of Southeast Asia flourished during the ninth to fourteenth centuries. Cambodia has a rich cultural heritage, but little is known about periods that preceded the founding of Angkor in A.D. 802. French archaeologists visited pre Angkorian sites throughout Indochina (particularly Cambodia and Viet Nam) and translated inscriptions from these sites between 1920 and 1950. -

Title: Understanding Material Offerings in Hong Kong Folk Religion Author: Kagan Pittman Source: Prandium - the Journal of Historical Studies, Vol

Title: Understanding Material Offerings in Hong Kong Folk Religion Author: Kagan Pittman Source: Prandium - The Journal of Historical Studies, Vol. 8, No. 1 (Fall, 2019). Published by: The Department of Historical Studies, University of Toronto Mississauga Stable URL: http://jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/prandium/article/view/16211/ 1 The following paper was written for the University of Toronto Mississauga’s RLG415: Advanced Topics in the Study of Religion.1 In this course we explored the topics of religion and death in Hong Kong. The trip to Hong Kong occurred during the 2019 Winter semester’s Reading Week. The final project could take any form the student wished, in consultation with the instructor, Ken Derry. The project was intended to explore a question posed by the student regarding religion and death in Hong Kong and answered using a combination of material from assigned readings in the class, our own experiences during the trip, and additional independent research. As someone with a history in professional writing, I chose for my final assignment to be in essay form. I selected material offerings as my subject given my history of interest with material religion, as in the expression of religion and religious ideas through physical mediums like art, and sacrificial as well as other sacred objects. --- Material offerings are an integral part to religious expression in Hong Kong’s Buddhist, Confucian and Taoist faith groups in varying degrees. Hong Kong’s folk religious practice, referred to as San Jiao (“Unity of the Three Teachings”) by Kwong Chunwah, Assistant Professor of Practical Theology at the Hong Kong Baptist Theological Seminary, combines key elements of these three faiths and so greatly influences the significance and use of material offerings, and explains much of what I have seen in Hong Kong over the course of a nine-day trip. -

Origin Narratives: Reading and Reverence in Late-Ming China

Origin Narratives: Reading and Reverence in Late-Ming China Noga Ganany Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2018 © 2018 Noga Ganany All rights reserved ABSTRACT Origin Narratives: Reading and Reverence in Late Ming China Noga Ganany In this dissertation, I examine a genre of commercially-published, illustrated hagiographical books. Recounting the life stories of some of China’s most beloved cultural icons, from Confucius to Guanyin, I term these hagiographical books “origin narratives” (chushen zhuan 出身傳). Weaving a plethora of legends and ritual traditions into the new “vernacular” xiaoshuo format, origin narratives offered comprehensive portrayals of gods, sages, and immortals in narrative form, and were marketed to a general, lay readership. Their narratives were often accompanied by additional materials (or “paratexts”), such as worship manuals, advertisements for temples, and messages from the gods themselves, that reveal the intimate connection of these books to contemporaneous cultic reverence of their protagonists. The content and composition of origin narratives reflect the extensive range of possibilities of late-Ming xiaoshuo narrative writing, challenging our understanding of reading. I argue that origin narratives functioned as entertaining and informative encyclopedic sourcebooks that consolidated all knowledge about their protagonists, from their hagiographies to their ritual traditions. Origin narratives also alert us to the hagiographical substrate in late-imperial literature and religious practice, wherein widely-revered figures played multiple roles in the culture. The reverence of these cultural icons was constructed through the relationship between what I call the Three Ps: their personas (and life stories), the practices surrounding their lore, and the places associated with them (or “sacred geographies”). -

LCSH Section H

H (The sound) H.P. 42 (Transport plane) Waha (African people) [P235.5] USE Handley Page H.P. 42 (Transport plane) BT Ethnology—Tanzania BT Consonants H.P. 80 (Jet bomber) Hāʾ (The Arabic letter) Phonetics USE Victor (Jet bomber) BT Arabic alphabet H-2 locus H.P. 115 (Jet planes) HA 132 Site (Niederzier, Germany) UF H-2 system USE Handley Page 115 (Jet planes) USE Hambach 132 Site (Niederzier, Germany) BT Immunogenetics H.P.11 (Bomber) HA 500 Site (Niederzier, Germany) H 2 regions (Astrophysics) USE Handley Page Type O (Bomber) USE Hambach 500 Site (Niederzier, Germany) USE H II regions (Astrophysics) H.P.12 (Bomber) HA 512 Site (Niederzier, Germany) H-2 system USE Handley Page Type O (Bomber) USE Hambach 512 Site (Niederzier, Germany) USE H-2 locus H.P. Sutton House (McCook, Neb.) HA 516 Site (Niederzier, Germany) H-8 (Computer) USE Sutton House (McCook, Neb.) USE Hambach 516 Site (Niederzier, Germany) USE Heathkit H-8 (Computer) H.R. 10 plans Ha-erh-pin chih Tʻung-chiang kung lu (China) H-34 Choctaw (Military transport helicopter) USE Keogh plans USE Ha Tʻung kung lu (China) USE Choctaw (Military transport helicopter) H.R.D. motorcycle Ha family (Not Subd Geog) H-43 (Military transport helicopter) (Not Subd Geog) USE Vincent H.R.D. motorcycle Ha ʻIvri (The Hebrew word) UF Huskie (Military transport helicopter) H-R diagrams USE ʻIvri (The Hebrew word) Kaman H-43 Huskie (Military transport USE HR diagrams Hà lăng (Southeast Asian people) helicopter) H regions (Astrophysics) USE Sedang (Southeast Asian people) Pedro (Military transport helicopter) USE H II regions (Astrophysics) Ha language (May Subd Geog) BT Military helicopters H.S.C. -

Toponyms of the Nanzhao Periphery/ John C

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 2003 Toponyms of the Nanzhao periphery/ John C. Lloyd University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Lloyd, John C., "Toponyms of the Nanzhao periphery/" (2003). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 1727. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/1727 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TOPONYMS OF THE NANZHAO PERIPHERY A Thesis Presented by John C. Lloyd Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2003 Chinese TOPONYMS OF THE NANZHAO PERIPHERY A Thesis Presented by John C. Lloyd Approved as to style and content by Zhongwei/Shen, Chair Alvin P. Cohen, Memb Piper Rae-Ciaubatz, Member Donald Gjertson, Department Head Asian Languages and Literatures TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF MAPS iv CHAPTER L THE NON-CHINESE TRIBES OF ANCIENT YUNNAN PROVINCE l 1.1 Introduction ^ 1 .2 Background of the Tai-Nanzhao Debate 9 II. TOPONYMS OF THE NANZHAO PERIPHERY 22 2.1 Explanation of Method 22 2.2 Historical Phonology of the Toponymic Elements 25 The Northwest 2.3 Border of Zhenla Eli, 7'^8'^enturies: Shaiiguo"f^i'and Can Ban #^ 27 2.4 The mang-/ head ^- element toponyms of the Nanzhao border areas 37 III. -

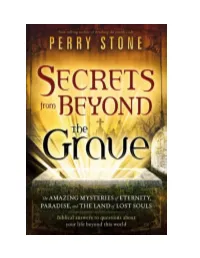

Secrets from Beyond the Grave by Perry Stone

Most Strang Communications Book Group products are available at special quantity discounts for bulk purchase for sales promotions, premiums, fund-raising, and educational needs. For details, write Strang Communications Book Group, 600 Rinehart Road, Lake Mary, Florida 32746, or telephone (407) 333-0600. Secrets From Beyond the Grave by Perry Stone Published by Charisma House A Strang Company 600 Rinehart Road Lake Mary, Florida 32746 www.strangbookgroup.com This book or parts thereof may not be reproduced in any form, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means--electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or otherwise--without prior written permission of the publisher, except as provided by United States of America copyright law. Unless otherwise noted, all Scripture quotations are from the New King James Version of the Bible. Copyright © 1979, 1980, 1982 by Thomas Nelson, Inc., publishers. Used by permission. Scripture quotations marked AMP are from the Amplified Bible. Old Testament copyright © 1965, 1987 by the Zondervan Corporation. The Amplified New Testament copyright © 1954, 1958, 1987 by the Lockman Foundation. Used by permission. Scripture quotations marked KJV are from the King James Version of the Bible. Scripture quotations marked RSV are from the Revised Standard Version of the Bible. Copyright © 1946, 1952, 1971 by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the USA. Used by permission. Quotations from the Quran are from The Quran Translation, 7th edition, translated by Abdullah Yusef Ali (Elmhurst, NY: Tahrike Tarsile Quran, Inc., 2001). Cover design by Justin Evans Design Director: Bill Johnson Copyright © 2010 by Perry Stone All rights reserved Visit the author's website at http://www.voe.org/.