Mathematical Economics at Cowles1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AHMED MUSHFIQ MOBARAK 165 Whitney Avenue, P.O

AHMED MUSHFIQ MOBARAK 165 Whitney Avenue, P.O. Box 208200, New Haven, CT 06520-8200 Phone: 203-432-5787 Email: [email protected] http://www.som.yale.edu/faculty/am833/ PROFESSIONAL POSITION Professor of Economics, Yale University, 2015 – Tenured in the School of Management (2015), and in the Department of Economics, FAS (2017) Faculty Director and Founder, Yale Research Initiative on Innovation and Scale (Y-RISE) 2018 - OTHER APPOINTMENTS Professorial Research Fellow, Dept. of Economics, Deakin University, Melbourne, Australia, 2018-2021 Lead, Bangladesh Research Program, International Growth Centre (IGC) at LSE and Oxford 2009 – Member, Bangladesh National Data Analytics Task Force (convened by ICT Minister), 2020 - Faculty Director, Yale Macmillan Center Program on Refugees and Forced Displacement 2018- Member, Panel of Economists, General Economics Division, Bangladesh Planning Commission, 2020 – Board Member and Scientific Advisor, Innovations for Poverty Action, 2015 – Academic Lead, Humanitarian and Forced Displacement Initiative, Innovations for Poverty Action 2020 - Executive Committee, Economic Growth Center, Yale University, 2019- (Affiliate, 2007-) Editorial Board, World Bank Economic Review, 2015 - Editorial Board, Asian Development Review, Asian Development Bank, 2018 - Consultant, World Bank and IFC 1998-2001 and 2009 – U.S. National Science Foundation, Member, Economics Program panel 2020-2022 University of Maryland Economics Leadership Council, 2018-2024 Technical Advisory Groups: UNHCR (Geneva) Safe Access to Fuel -

Lecture Notes1 Mathematical Ecnomics

Lecture Notes1 Mathematical Ecnomics Guoqiang TIAN Department of Economics Texas A&M University College Station, Texas 77843 ([email protected]) This version: August, 2020 1The most materials of this lecture notes are drawn from Chiang’s classic textbook Fundamental Methods of Mathematical Economics, which are used for my teaching and con- venience of my students in class. Please not distribute it to any others. Contents 1 The Nature of Mathematical Economics 1 1.1 Economics and Mathematical Economics . 1 1.2 Advantages of Mathematical Approach . 3 2 Economic Models 5 2.1 Ingredients of a Mathematical Model . 5 2.2 The Real-Number System . 5 2.3 The Concept of Sets . 6 2.4 Relations and Functions . 9 2.5 Types of Function . 11 2.6 Functions of Two or More Independent Variables . 12 2.7 Levels of Generality . 13 3 Equilibrium Analysis in Economics 15 3.1 The Meaning of Equilibrium . 15 3.2 Partial Market Equilibrium - A Linear Model . 16 3.3 Partial Market Equilibrium - A Nonlinear Model . 18 3.4 General Market Equilibrium . 19 3.5 Equilibrium in National-Income Analysis . 23 4 Linear Models and Matrix Algebra 25 4.1 Matrix and Vectors . 26 i ii CONTENTS 4.2 Matrix Operations . 29 4.3 Linear Dependance of Vectors . 32 4.4 Commutative, Associative, and Distributive Laws . 33 4.5 Identity Matrices and Null Matrices . 34 4.6 Transposes and Inverses . 36 5 Linear Models and Matrix Algebra (Continued) 41 5.1 Conditions for Nonsingularity of a Matrix . 41 5.2 Test of Nonsingularity by Use of Determinant . -

Competing for Talent

COMPETING FOR TALENT By Yuhta Ishii, Aniko Öry, and Adrien Vigier February 2018 COWLES FOUNDATION DISCUSSION PAPER NO. 2119 COWLES FOUNDATION FOR RESEARCH IN ECONOMICS YALE UNIVERSITY Box 208281 New Haven, Connecticut 06520-8281 http://cowles.yale.edu/ Competing for Talent Yuhta Ishii, Aniko Ory,¨ and Adrien Vigier∗ First Draft: August 2015 This Draft: February 2018 Abstract In many labor markets, e.g., for lawyers, consultants, MBA students, and professional sport players, workers get offered and sign long-term contracts even though waiting could reveal significant information about their capabilities. This phenomenon is called unraveling. We examine the link between wage bargaining and unraveling. Two firms, an incumbent and an entrant, compete to hire a worker of unknown talent. Informational frictions prevent the incumbent from always observing the entrant's arrival, inducing unraveling in all equilibria. We analyze the extent of unraveling, surplus shares, the average talent of employed workers, and the distribution of wages within and across firms. Keywords: Unraveling, Talent, Wage Bargaining, Competition, Uncertainty. JEL Codes: C7, D8, J3 ∗Ishii: ITAM, Centro de Investigaci´onEcon´omica,Mexico, email: [email protected]; Ory:¨ Yale Uni- versity, School of Management, New Haven, CT 06511, email: [email protected]; Vigier: BI Norwegian Business School, email: [email protected]. We thank Nicholas Chow and Hungni Chen for excellent research assistance. We are grateful to Dirk Bergemann, Simon Board, Joyee Deb, Jeff Ely, Brett Green, Jo- hannes H¨orner,Lisa Kahn, Teddy Kim, Sebastian Kodritsch, Fei Li, Ilse Lindenlaub, Espen Moen, Guiseppe Moscarini, Pauli Murto, Peter Norman, Theodore Papageorgiou, Larry Samuelson, Utku Unver,¨ Leeat Yariv, Juuso Valimaki for helpful discussions and comments. -

Mathematical Economics - B.S

College of Mathematical Economics - B.S. Arts and Sciences The mathematical economics major offers students a degree program that combines College Requirements mathematics, statistics, and economics. In today’s increasingly complicated international I. Foreign Language (placement exam recommended) ........................................... 0-14 business world, a strong preparation in the fundamentals of both economics and II. Disciplinary Requirements mathematics is crucial to success. This degree program is designed to prepare a student a. Natural Science .............................................................................................3 to go directly into the business world with skills that are in high demand, or to go on b. Social Science (completed by Major Requirements) to graduate study in economics or finance. A degree in mathematical economics would, c. Humanities ....................................................................................................3 for example, prepare a student for the beginning of a career in operations research or III. Laboratory or Field Work........................................................................................1 actuarial science. IV. Electives ..................................................................................................................6 120 hours (minimum) College Requirement hours: ..........................................................13-27 Any student earning a Bachelor of Science (BS) degree must complete a minimum of 60 hours in natural, -

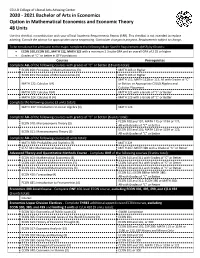

2020-2021 Bachelor of Arts in Economics Option in Mathematical

CSULB College of Liberal Arts Advising Center 2020 - 2021 Bachelor of Arts in Economics Option in Mathematical Economics and Economic Theory 48 Units Use this checklist in combination with your official Academic Requirements Report (ARR). This checklist is not intended to replace advising. Consult the advisor for appropriate course sequencing. Curriculum changes in progress. Requirements subject to change. To be considered for admission to the major, complete the following Major Specific Requirements (MSR) by 60 units: • ECON 100, ECON 101, MATH 122, MATH 123 with a minimum 2.3 suite GPA and an overall GPA of 2.25 or higher • Grades of “C” or better in GE Foundations Courses Prerequisites Complete ALL of the following courses with grades of “C” or better (18 units total): ECON 100: Principles of Macroeconomics (3) MATH 103 or Higher ECON 101: Principles of Microeconomics (3) MATH 103 or Higher MATH 111; MATH 112B or 113; All with Grades of “C” MATH 122: Calculus I (4) or Better; or Appropriate CSULB Algebra and Calculus Placement MATH 123: Calculus II (4) MATH 122 with a Grade of “C” or Better MATH 224: Calculus III (4) MATH 123 with a Grade of “C” or Better Complete the following course (3 units total): MATH 247: Introduction to Linear Algebra (3) MATH 123 Complete ALL of the following courses with grades of “C” or better (6 units total): ECON 100 and 101; MATH 115 or 119A or 122; ECON 310: Microeconomic Theory (3) All with Grades of “C” or Better ECON 100 and 101; MATH 115 or 119A or 122; ECON 311: Macroeconomic Theory (3) All with -

The Rise and Fall of Walrasian General Equilibrium Theory: the Keynes Effect

The Rise and Fall of Walrasian General Equilibrium Theory: The Keynes Effect D. Wade Hands Department of Economics University of Puget Sound Tacoma, WA USA [email protected] Version 1.3 September 2009 15,246 Words This paper was initially presented at The First International Symposium on the History of Economic Thought “The Integration of Micro and Macroeconomics from a Historical Perspective,” University of São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil, August 3-5, 2009. Abstract: Two popular claims about mid-to-late twentieth century economics are that Walrasian ideas had a significant impact on the Keynesian macroeconomics that became dominant during the 1950s and 1060s, and that Arrow-Debreu Walrasian general equilibrium theory passed its zenith in microeconomics at some point during the 1980s. This paper does not challenge either of these standard interpretations of the history of modern economics. What the paper argues is that there are at least two very important relationships between Keynesian economics and Walrasian general equilibrium theory that have not generally been recognized within the literature. The first is that influence ran not only from Walrasian theory to Keynesian, but also from Keynesian theory to Walrasian. It was during the neoclassical synthesis that Walrasian economics emerged as the dominant form of microeconomics and I argue that its compatibility with Keynesian theory influenced certain aspects of its theoretical content and also contributed to its success. The second claim is that not only did Keynesian economics contribute to the rise Walrasian general equilibrium theory, it has also contributed to its decline during the last few decades. The features of Walrasian theory that are often suggested as its main failures – stability analysis and the Sonnenschein-Mantel-Debreu theorems on aggregate excess demand functions – can be traced directly to the features of the Walrasian model that connected it so neatly to Keynesian macroeconomics during the 1950s. -

Nine Lives of Neoliberalism

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Plehwe, Dieter (Ed.); Slobodian, Quinn (Ed.); Mirowski, Philip (Ed.) Book — Published Version Nine Lives of Neoliberalism Provided in Cooperation with: WZB Berlin Social Science Center Suggested Citation: Plehwe, Dieter (Ed.); Slobodian, Quinn (Ed.); Mirowski, Philip (Ed.) (2020) : Nine Lives of Neoliberalism, ISBN 978-1-78873-255-0, Verso, London, New York, NY, https://www.versobooks.com/books/3075-nine-lives-of-neoliberalism This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/215796 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative -

Impact of Trade on the Characteristics of the Digital Newspaper Market New Empirical Evidence from Francophone Africa

Impact of Trade on the Characteristics of the Digital Newspaper Market New Empirical Evidence from Francophone Africa Anaïs Galdin May 22th, 2017 Abstract This paper provides a first empirical study of how openness to international trade in news products, a phenomenon largely facilitated by the digitalization of newspapers, may impact the characteristics of the information products available to consumers. Based on acasestudyoftheentryofFrenchmediafirmsinFrancophoneAfrica,webuildanew dataset of more than 800 000 newspaper articles over the period 2005 to 2017. Using text mining techniques, we construct a five-dimensional set of newspaper characteristics to qualitatively analyze newspaper data. Our evidences suggest that the entry of French digital newspapers, which produce a relatively low share of local news and whose websites are generally uniformly targeting all Francophone African countries, lead to a significant decrease of the diversity of subjects treated by Francophone African newspapers, charac- terized by a strong and significant increase of the share of local news, and a small decrease of the total number of articles related to France. We also find a slight but significant impact of the penetration of French digital newspapers on two indicators of newspaper format, namely a small increase of the average frequency of publication of Francophone African newspapers, and a very small decrease of the mean wordcount per articles. We believe the specific format of the news displayed on the web, generally significantly shorter than printed articles and with a higher publication rate, could explain the weakness of the effect on these two indicators.1 1I would like to thank my advisors, Julia CAGE and Thomas CHANEY, for their time, constructive discussions and invaluable advice. -

Econ5153 Mathematical Economics

ECON5153 MATHEMATICAL ECONOMICS University of Oklahoma, Fall 2014 Tuesday and Thursday, 9-10:15am, Cate Center CCD1 338 Instructor: Qihong Liu Office: CCD1 426 Phone: 325-5846 E-mail: [email protected] Office Hours: Tuesday and Thursday, 1:30-2:30pm, and by appointment Course Description This is the first course in the graduate Mathematical Economics/Econometrics sequence. The objective of this course is to acquaint the students with the fundamental mathematical techniques used in modern economics, including Matrix Algebra, Optimization and Dynam- ics. Upon completion of the course students will be able to set up and analytically solve constrained and unconstrained optimization problems. The students will also be able to solve linear difference equations and differential equations. Textbooks Required: Simon and Blume: Mathematics for Economists, W.W.Norton, 1994. Other useful books available on reserve at Bizzell: Chiang and Wainwright: Fundamental Methods of Mathematical Economics, McGraw-Hill, Fourth Edition, 2005. Darrell A. Turkington: Mathematical Tools for Economics, Blackwell Publishing, 2007. Avinash Dixit: Optimization in Economic Theory, Oxford University Press, Second Edition, 1990. Michael D. Intriligator: Mathematical Optimization and Economic Theory, Prentice-Hall, 1971. Assessment Grades are based on homework (15%), class participation (10%), two midterm exams (20% each) and final exam (35%). You are encouraged to form study groups to discuss homework and lecture materials. All exams will be in closed-book forms. Problem Sets Several problem sets will be assigned during the semester. You will have at least one week to complete each assignment. Late homework will not be accepted. You are allowed to work 1 with other students in this class on the problem sets, but each student must write his or her own answers. -

Casting Net Assessment Andrew W

THE 16 DREW PER PA S Casting Net Assessment Andrew W. Marshall and the Epistemic Community of the Cold War John M. Schutte Lieutenant Colonel, USAF Air University Steven L. Kwast, Lieutenant General, Commander and President School of Advanced Air and Space Studies Thomas D. McCarthy, Colonel, Commandant and Dean AIR UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF ADVANCED AIR AND SPACE STUDIES Casting Net Assessment Andrew W. Marshall and the Epistemic Community of the Cold War John M. Schutte Lieutenant Colonel, USAF Drew Paper No. 16 Air University Press Air Force Research Institute Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama Project Editor Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Jeanne K. Shamburger Schutte, John M., 1976– Copy Editor Casting net assessment : Andrew W. Marshall and the epistemic Carolyn Burns community of the Cold War / John M. Schutte, Lieutenant Colonel, USAF. Cover Art, Book Design, and Illustrations pages cm. — (Drew paper ; no. 16) Daniel L. Armstrong Includes bibliographical references. Composition and Prepress Production ISBN 978-1-58566-240-1 (alk. paper) Nedra O. Looney 1. Marshall, Andrew W., 1921– 2. United States. Department of Defense. Director of Net Assessment—Biography. 3. United Print Preparation and Distribution States. Department of Defense—Officials and employees— Diane Clark Biography. 4 Rand Corporation—Biography. 5. United States— Forecasting. 6. Military planning—United States—History— 20th century. 7. Military planning—United States—History—21st century. 8. United States—Military policy. 9. Strategy. 10. Cold War. I. Title. II. Title: Andrew W. Marshall and the epistemic community of the Cold War. UA23.6.S43 2014 AIR FORCE RESEARCH INSTITUTE 355.0092—dc23 [B] AIR UNIVERSITY PRESS 2014035197 Director and Publisher Allen G. -

Paul Samuelson's Ways to Macroeconomic Dynamics

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Boianovsky, Mauro Working Paper Paul Samuelson's ways to macroeconomic dynamics CHOPE Working Paper, No. 2019-08 Provided in Cooperation with: Center for the History of Political Economy at Duke University Suggested Citation: Boianovsky, Mauro (2019) : Paul Samuelson's ways to macroeconomic dynamics, CHOPE Working Paper, No. 2019-08, Duke University, Center for the History of Political Economy (CHOPE), Durham, NC This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/196831 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu Paul Samuelson’s Ways to Macroeconomic Dynamics by Mauro Boianovsky CHOPE Working Paper No. 2019-08 May 2019 Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3386201 1 Paul Samuelson’s ways to macroeconomic dynamics Mauro Boianovsky (Universidade de Brasilia) [email protected] First preliminary draft. -

Mathematical Economics

ECONOMICS 113: Mathematical Economics Fall 2016 Basic information Lectures Tu/Th 14:00-15:20 PCYNH 120 Instructor Prof. Alexis Akira Toda Office hours Tu/Th 13:00-14:00, ECON 211 Email [email protected] Webpage https://sites.google.com/site/aatoda111/ (Go to Teaching ! Mathematical Economics) TA Miles Berg, Econ 128, [email protected] (Office hours: TBD) Course description Carl Friedrich Gauss said mathematics is the queen of the sciences (and number theory is the queen of mathematics).1 Paul Samuelson said economics is the queen of the social sciences.2 Not surprisingly, modern economics is a highly mathematical subject. Mathematical economics studies the mathematical foundations of economic theory in the approach known as the Arrow-Debreu model of general equilibrium. Partial equilibrium (things like demand and supply curves), which you have probably learned in Econ 100ABC, considers each market separately. General equilibrium (GE for short), on the other hand, considers the economy as a whole, taking into account the interaction of all markets. Econ 113 is probably the most mathematically advanced undergraduate course of- fered at UCSD Economics, but it should have a high return. In the course, we will develop a mathematical model of classical economic thoughts like Bentham's \greatest happiness principle" and Smith's \invisible hand", and prove theorems. Then we will apply the theory to international trade, finance, social security, etc. Time permitting, I will talk about my own research. Prerequisites A year of calculus and a year of upper division microeconomic theory (at UCSD these courses are Math 20ABC and Economics 100ABC) are required.