The Rise and Fall of Walrasian General Equilibrium Theory: the Keynes Effect

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lecture Notes1 Mathematical Ecnomics

Lecture Notes1 Mathematical Ecnomics Guoqiang TIAN Department of Economics Texas A&M University College Station, Texas 77843 ([email protected]) This version: August, 2020 1The most materials of this lecture notes are drawn from Chiang’s classic textbook Fundamental Methods of Mathematical Economics, which are used for my teaching and con- venience of my students in class. Please not distribute it to any others. Contents 1 The Nature of Mathematical Economics 1 1.1 Economics and Mathematical Economics . 1 1.2 Advantages of Mathematical Approach . 3 2 Economic Models 5 2.1 Ingredients of a Mathematical Model . 5 2.2 The Real-Number System . 5 2.3 The Concept of Sets . 6 2.4 Relations and Functions . 9 2.5 Types of Function . 11 2.6 Functions of Two or More Independent Variables . 12 2.7 Levels of Generality . 13 3 Equilibrium Analysis in Economics 15 3.1 The Meaning of Equilibrium . 15 3.2 Partial Market Equilibrium - A Linear Model . 16 3.3 Partial Market Equilibrium - A Nonlinear Model . 18 3.4 General Market Equilibrium . 19 3.5 Equilibrium in National-Income Analysis . 23 4 Linear Models and Matrix Algebra 25 4.1 Matrix and Vectors . 26 i ii CONTENTS 4.2 Matrix Operations . 29 4.3 Linear Dependance of Vectors . 32 4.4 Commutative, Associative, and Distributive Laws . 33 4.5 Identity Matrices and Null Matrices . 34 4.6 Transposes and Inverses . 36 5 Linear Models and Matrix Algebra (Continued) 41 5.1 Conditions for Nonsingularity of a Matrix . 41 5.2 Test of Nonsingularity by Use of Determinant . -

Mathematical Economics - B.S

College of Mathematical Economics - B.S. Arts and Sciences The mathematical economics major offers students a degree program that combines College Requirements mathematics, statistics, and economics. In today’s increasingly complicated international I. Foreign Language (placement exam recommended) ........................................... 0-14 business world, a strong preparation in the fundamentals of both economics and II. Disciplinary Requirements mathematics is crucial to success. This degree program is designed to prepare a student a. Natural Science .............................................................................................3 to go directly into the business world with skills that are in high demand, or to go on b. Social Science (completed by Major Requirements) to graduate study in economics or finance. A degree in mathematical economics would, c. Humanities ....................................................................................................3 for example, prepare a student for the beginning of a career in operations research or III. Laboratory or Field Work........................................................................................1 actuarial science. IV. Electives ..................................................................................................................6 120 hours (minimum) College Requirement hours: ..........................................................13-27 Any student earning a Bachelor of Science (BS) degree must complete a minimum of 60 hours in natural, -

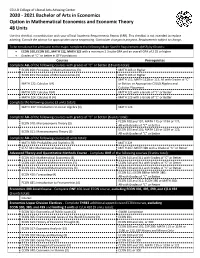

2020-2021 Bachelor of Arts in Economics Option in Mathematical

CSULB College of Liberal Arts Advising Center 2020 - 2021 Bachelor of Arts in Economics Option in Mathematical Economics and Economic Theory 48 Units Use this checklist in combination with your official Academic Requirements Report (ARR). This checklist is not intended to replace advising. Consult the advisor for appropriate course sequencing. Curriculum changes in progress. Requirements subject to change. To be considered for admission to the major, complete the following Major Specific Requirements (MSR) by 60 units: • ECON 100, ECON 101, MATH 122, MATH 123 with a minimum 2.3 suite GPA and an overall GPA of 2.25 or higher • Grades of “C” or better in GE Foundations Courses Prerequisites Complete ALL of the following courses with grades of “C” or better (18 units total): ECON 100: Principles of Macroeconomics (3) MATH 103 or Higher ECON 101: Principles of Microeconomics (3) MATH 103 or Higher MATH 111; MATH 112B or 113; All with Grades of “C” MATH 122: Calculus I (4) or Better; or Appropriate CSULB Algebra and Calculus Placement MATH 123: Calculus II (4) MATH 122 with a Grade of “C” or Better MATH 224: Calculus III (4) MATH 123 with a Grade of “C” or Better Complete the following course (3 units total): MATH 247: Introduction to Linear Algebra (3) MATH 123 Complete ALL of the following courses with grades of “C” or better (6 units total): ECON 100 and 101; MATH 115 or 119A or 122; ECON 310: Microeconomic Theory (3) All with Grades of “C” or Better ECON 100 and 101; MATH 115 or 119A or 122; ECON 311: Macroeconomic Theory (3) All with -

Nine Lives of Neoliberalism

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Plehwe, Dieter (Ed.); Slobodian, Quinn (Ed.); Mirowski, Philip (Ed.) Book — Published Version Nine Lives of Neoliberalism Provided in Cooperation with: WZB Berlin Social Science Center Suggested Citation: Plehwe, Dieter (Ed.); Slobodian, Quinn (Ed.); Mirowski, Philip (Ed.) (2020) : Nine Lives of Neoliberalism, ISBN 978-1-78873-255-0, Verso, London, New York, NY, https://www.versobooks.com/books/3075-nine-lives-of-neoliberalism This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/215796 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative -

Econ5153 Mathematical Economics

ECON5153 MATHEMATICAL ECONOMICS University of Oklahoma, Fall 2014 Tuesday and Thursday, 9-10:15am, Cate Center CCD1 338 Instructor: Qihong Liu Office: CCD1 426 Phone: 325-5846 E-mail: [email protected] Office Hours: Tuesday and Thursday, 1:30-2:30pm, and by appointment Course Description This is the first course in the graduate Mathematical Economics/Econometrics sequence. The objective of this course is to acquaint the students with the fundamental mathematical techniques used in modern economics, including Matrix Algebra, Optimization and Dynam- ics. Upon completion of the course students will be able to set up and analytically solve constrained and unconstrained optimization problems. The students will also be able to solve linear difference equations and differential equations. Textbooks Required: Simon and Blume: Mathematics for Economists, W.W.Norton, 1994. Other useful books available on reserve at Bizzell: Chiang and Wainwright: Fundamental Methods of Mathematical Economics, McGraw-Hill, Fourth Edition, 2005. Darrell A. Turkington: Mathematical Tools for Economics, Blackwell Publishing, 2007. Avinash Dixit: Optimization in Economic Theory, Oxford University Press, Second Edition, 1990. Michael D. Intriligator: Mathematical Optimization and Economic Theory, Prentice-Hall, 1971. Assessment Grades are based on homework (15%), class participation (10%), two midterm exams (20% each) and final exam (35%). You are encouraged to form study groups to discuss homework and lecture materials. All exams will be in closed-book forms. Problem Sets Several problem sets will be assigned during the semester. You will have at least one week to complete each assignment. Late homework will not be accepted. You are allowed to work 1 with other students in this class on the problem sets, but each student must write his or her own answers. -

Paul Samuelson's Ways to Macroeconomic Dynamics

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Boianovsky, Mauro Working Paper Paul Samuelson's ways to macroeconomic dynamics CHOPE Working Paper, No. 2019-08 Provided in Cooperation with: Center for the History of Political Economy at Duke University Suggested Citation: Boianovsky, Mauro (2019) : Paul Samuelson's ways to macroeconomic dynamics, CHOPE Working Paper, No. 2019-08, Duke University, Center for the History of Political Economy (CHOPE), Durham, NC This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/196831 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu Paul Samuelson’s Ways to Macroeconomic Dynamics by Mauro Boianovsky CHOPE Working Paper No. 2019-08 May 2019 Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3386201 1 Paul Samuelson’s ways to macroeconomic dynamics Mauro Boianovsky (Universidade de Brasilia) [email protected] First preliminary draft. -

Mathematical Economics

ECONOMICS 113: Mathematical Economics Fall 2016 Basic information Lectures Tu/Th 14:00-15:20 PCYNH 120 Instructor Prof. Alexis Akira Toda Office hours Tu/Th 13:00-14:00, ECON 211 Email [email protected] Webpage https://sites.google.com/site/aatoda111/ (Go to Teaching ! Mathematical Economics) TA Miles Berg, Econ 128, [email protected] (Office hours: TBD) Course description Carl Friedrich Gauss said mathematics is the queen of the sciences (and number theory is the queen of mathematics).1 Paul Samuelson said economics is the queen of the social sciences.2 Not surprisingly, modern economics is a highly mathematical subject. Mathematical economics studies the mathematical foundations of economic theory in the approach known as the Arrow-Debreu model of general equilibrium. Partial equilibrium (things like demand and supply curves), which you have probably learned in Econ 100ABC, considers each market separately. General equilibrium (GE for short), on the other hand, considers the economy as a whole, taking into account the interaction of all markets. Econ 113 is probably the most mathematically advanced undergraduate course of- fered at UCSD Economics, but it should have a high return. In the course, we will develop a mathematical model of classical economic thoughts like Bentham's \greatest happiness principle" and Smith's \invisible hand", and prove theorems. Then we will apply the theory to international trade, finance, social security, etc. Time permitting, I will talk about my own research. Prerequisites A year of calculus and a year of upper division microeconomic theory (at UCSD these courses are Math 20ABC and Economics 100ABC) are required. -

Economics and Neoliberalism 25/11/05

essay for After Blair: Politics After the New Labour Decade, forthcoming summer 2006 Economics and Neoliberalism 25/11/05 Edward Fullbrook Neoliberalism is the ideology of our time. And of New Labour and Tony Blair. What happens after Blair becomes seriously interesting if we suppose that within the Labour Party Neoliberalism could be dethroned. Although this event hardly appears immanent, it could be brought forward if the nature and location of the breeding ground of the Neoliberal beast became public knowledge. For a quarter of a century people to the left of what was once a staunchly right-wing position (too rightwing for the rightwing of the Labour Party) have been struggling against Neoliberalism with ever diminishing success. This failure has taken place despite much cogent analysis of the sociological and geopolitical forces fuelling the Neoliberal conquest. The working assumption has been that if Neoliberalism’s books could be opened so that the world could see who its real winners and losers were and the extent of their winnings and loses, then citizens would see the light and politicians of good will would repent and political process would once again enter into a progressive era. This essay breaks with that tradition. While I wholeheartedly agree that the analysis described above is a necessary condition for stopping Neoliberalism, I am no less certain that it is not by itself a sufficient condition. Understanding the consequences of Neoliberalism is not enough. We also must understand where this intellectual poison comes from and the primary channel by which it continues to be injected into the body politic. -

Mathematical Economics at Cowles1

Mathematical Economics at Cowles1 Gerard Debreu Presented at The Cowles Fiftieth Anniversary Celebration, June 3, 1983 Introduction The first fifty years of Cowles were a period of profound and far-reaching transformation in the field of mathematical economics. A few numbers help one to perceive the depth and the extent of the change that took place in the half-century just ended. Both Econometrica and The Review of Economic Studies began publication in 1933. The first volume of the former for the calendar year 1933 and the first volume of the latter for the academic year 1933–34, together, devoted 165 pages to articles contributing to mathematical economics, by a liberal definition of terms. According to a stricter definition, the corresponding number of pages for the year 1982 was close to 4,000 for the five main periodicals in the field (Econometrica, Review of Economic Studies, International Economic Review, Journal of Economic Theory, and Journal of Mathematical Economics). No less remarkable was the metamorphosis of the American Economic Review. Its entire volume for the year 1933 contained exactly four pages where any mathematical symbol appeared, and two of them were in the Book Review Section. In contrast, in 1982 only five of the fifty-two articles published by the A.E.R. were free from mathematical expressions. Still another index of the rapid growth of mathematical economics during that period can be found in the increase in membership of the Econometric Society, which went from 163 on January 1, 1932 to 2,987 in 1982. Having heeded the demanding motto “Science is Measurement,” under which the Cowles Commission worked for its first twenty years, we may look at non-quantifiable aspects of the development of mathematical economics from the early thirties to the present. -

BA in Economics-Mathematical Economics

B.A. in Economics-Mathematical Economics Economics is the study of how individuals and societies organize the production and distribution of goods and services. Economics is also concerned with the historical development of economies along with how various groups and classes interact within the economy. All policy issues in modern societies have an economic dimension, and so the study of economics provides students the ability to understand many of the fundamental problems faced by society. Further, because economics emphasizes systematic thinking and the analysis of data, training in economics offers excellent preparation for careers in industry, nonprofits, and government. Economics also provides excellent preparation for many professions including law, education, public administration, and management. OVERVIEW OF MAJOR SALARY OUTLOOK The B.A. in Economics: Mathematical Economics provides What you major in has a bigger impact on your future the student with rigorous training in economic theory, data earnings than what school you attend. For instance, surveys analysis, and the analysis of public policy. It also provides show that those who major in economics earn, on average, students with a solid foundation of mathematics. more both in their first jobs and in mid-career than those who major in almost all other majors, including Finance, The major involves a consideration of how individuals, Business, Mathematics, Sociology, Political Science, and firms, and governments balance costs and benefits to Psychology. achieve their goals. Further, the major considers the larger institutional and macroeconomics structures that shape the The likely reasons for these higher earnings include that decisions of economic and non-economic actors. economics majors can go into many different fields and receive analytical training that is valued highly by many CAREER OPPORTUNITIES employers. -

Mathematical Analysis in Static Equilibrium of Economics: As Support to Microeconomics Course

MATHEMATICAL ANALYSIS IN STATIC EQUILIBRIUM OF ECONOMICS: AS SUPPORT TO MICROECONOMICS COURSE Yadav Mani Upadhyaya, PhD * Abstract Microeconomics studies the economic behavior of individual decision-makers. To be able to make sound decisions in economics, the economist has designed mathematical models based on the differentiation of simple functions. Economics and mathematics are directly related as changes in quantities and variables affect the relationship and the direction of the consumer behavior to become better –off or worse-off. The main objectives of this study are microeconomic theories that may simplify or easily understandable through the mathematical calculation to illustrate the examples and calculate the equilibrium positions numerically. The study also aims to provide mathematical tools that manage to determine all the information necessary for decision making from a broad vision. The relationship between quantity and price may be better explained through mathematical notations. The supply and demand curve is designed to find the equilibrium point and it is better explained through mathematical equations. To explain, the methodology is used for a simple mathematical function of price with the help of a simple linear and nonlinear model of static analysis of the market equilibrium of Qd=Qs. This study concludes that it will greatly help college students, professionals, entrepreneurs, and in general anyone presents solved exercise and proposes problems, for the student to solve cases create graphs, table, and interpret and analyze results in the market and thus fixing the knowledge. Keywords: Microeconomics, mathematical function, market equilibrium, decision making, variable, relation JEL: D00, C30, C62 Introduction The proposed topic is important, due to the need of the professionals of the social sciences to possess tools that allow adapting the entire mathematical technical base, to the analysis of productivity and costs to help you adapt to market demands labor within the context of globalization. -

Mathematical Economics (MECO) 1

Mathematical Economics (MECO) 1 MATHEMATICAL ECONOMICS (MECO) Faculty Director: KB Boomer (Mathematics) Coordinating Committee: Marcellus Andrews (Economics), Erdogan Bakir (Economics), Kelly A. Bickel (Mathematics), KB Boomer (Mathematics), Thomas C. Kinnaman (Economics), Nathan C. Ryan (Mathematics) Mathematics has traditionally served as the language of the natural sciences, and more recently it has become a useful tool in the social sciences, particularly in economics. The Bachelor of Science in Mathematical Economics at Bucknell University was developed jointly by the Department of Mathematics and the Department of Economics. It is a coordinated curriculum that incorporates economics, mathematics, and statistics to provide the strong foundations that offer students both the intellectual and the quantitative skills to grapple with questions at the interface of these two disciplines. Students interested in economics and mathematics could also consider a double major in economics and mathematics within the B.A. degree program, or combine a B.A. in one of these disciplines with an academic minor in the other. Students who plan to attend graduate school in economics might consider the Mathematical Economics major, focusing on the theoretical track, and add MATH 304 Statistical Inference Theory. Students undecided among these options are encouraged to contact a member of the coordinating committee. Mathematical Economics Major The B.S. major in Mathematical Economics requires a total of 18 credits, eight from economics and 10 from mathematics. Required Economics Courses ECON 103 Economic Principles and Problems 1 ECON 257 Intermediate Macroeconomic 1 1 ECON 258 Intermediate Political Economy 1 1 ECON 259 Intermediate Mathematical Microeconomics 1 1 ECON 341 Econometrics 1 Two economics courses 2 2 Senior Seminar ECON 441 Advanced Econometrics 1 Total Credits 8 1 The senior seminar ECON 441 Advanced Econometrics will serve as the Culminating Experience for the MECO major, and will also address the speaking goal of the College Core Curriculum (CCC).