Samuelson, Keynes and the Search for a General Theory of Economics Backhouse, Roger

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Political Economy in Macroeconomics I Allan Drazen

account libcralization as a signal of commitmcnt to economic reform. Wc also summarizc thc empirical rcscarch on political determinants of capital Political Economy in controls. Another major issue in open-economy macroeconomics is sovereign Macroeconomics debt, that is, the debt owed by a government to foreign creditors. hsucs of sovereign debt arc substantially different than those concerning nonsovereign debt and arc inherently political. For example, since it is oWed by the government, repayment decisions are not connectcd with any question of the ability to repay. With few exceptions, a borrower country has the technical ability to repay the debt, so that non-repayment is a ALLAN DRAZEN political issue. In Section 12.8, we analyze basic models of sovereign ,c,, borrowing and its repayment, especially the role of penalties in enforcing repayment. We also consider the importance of political versus nonpoliti cal penalties in the decision of whether to issue debt at home or abroad. Copyright © 2000 by Princeton University Press The final topic considered is foreign assistance, especially lending by Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, governments and international financial organizations to developing coun Princeton, New Jersey 08540 tries for the purpose of structural adjustment. Our point of departure is In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, the strikingly disappointing results that foreign aid programs have had in Chichester, West Sussex alleviating poverty and stimulating growth in the recipient countries, a All Rights Resm;ed failure that we argue reflects the political nature of aid. Foreign assistance is inherently political for a number of reasons. First, the incentives of the donors may be political, not only in the obvious sense that aid is often given for strategic political reasons, but also because the nature of aid (and Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data especially its ineffectiveness) often reflects political and bureaucratic con flicts within the donor organizations. -

A WILPF Guide to Feminist Political Economy

A WILPF GUIDE TO FEMINIST POLITICAL ECONOMY Brief for WILPF members Table of Contents Advancing WILPF’s approach to peace . 2 Political economy as a tool . 4 A feminist twist to understanding political economy . 4 Feminist political economy in the context of neoliberal policies . 5 Gendered economy of investments . 7 Feminist political economy analysis - How does WILPF do it? . 9 What questions do we need to ask? . 10 Case study . 12 © 2018 Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom August 2018 A User Guide to Feminist Political Economy 2nd Edition 13 pp. Authors: Nela Porobic Isakovic Editors: Nela Porobic Isakovic, Nina Maria Hansen, Cover photo Madeleine Rees, Gorana Mlinarevic Brick wall painting of faces by Design: Nadia Joubert Oliver Cole (@oliver_photographer) www.wilpf.org on Unsplash.com 1 Advancing WILPF’s approach to peace HOW CAN FEMINIST UNDERSTANDING OF POLITICAL ECONOMY IN CONFLICT OR POST-CONFLICT CONTEXT HELP ADVANCE WILPF’S APPROACH TO PEACE? Political economy makes explicit linkages between political, economic and social factors. It is concerned with how politics can influence the economy. It looks at the access to, and distribution of wealth and power in order to understand why, by whom, and for whom certain decisions are taken, and how they affect societies – politically, economically and socially. It combines different sets of academic disciplines, most notably political science, economy and sociology, but also law, history and other disciplines. By using feminist political economy, WILPF seeks to understand the broader context of war and post-conflict recovery, and to deconstruct seemingly fixed and unchangeable economic, social, and political parameters. -

The Political Economy of Adjustment and Rebalancing

May 2014 The Political Economy of Adjustment and Rebalancing Jeffry Frieden Department of Government Harvard University This essay is based on an address to the JIMF-USC Conference on Financial Adjustment in the Aftermath of the Global Crisis, Los Angeles, April 18-19, 2014. The author thanks Joshua Aizenman, Lawrence Broz, Menzie Chinn, Dani Rodrik, Kenneth Rogoff, Francesco Trebbi, and Stefanie Walter for very helpful comments and suggestions. 2 The world’s recovery from the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) was extraordinarily slow and difficult. In the United States, it took some fifty months for employment to return to pre-crisis levels. This contrasts dramatically with the norm in American recessions: since the 1930s, employment has on average taken about ten months to return to pre-recession levels. 1 Output, similarly, regained its pre-crisis levels far more slowly than in other post-Depression recessions. And five years after the crisis began, median household income was still over 8 percent below its pre-crisis level. 2 Recovery in Europe was even slower and more difficult. The region fell into a second recession soon after the first one ended; unemployment soared in many countries, and has remained extremely high for a very long time. The painful recovery was due in part to the severity of the crisis itself. The Global Financial Crisis was, after all, the longest downturn since the 1940s, and the steepest 1 Employment reached pre-recession levels in May 2014. For previous experiences, see http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2013/09/25/at-42-months-and-counting-current- job-recovery-is-slowest-since-truman-was-president/ accessed May 16, 2014 2 http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2013/09/18/four-takeaways-from-tuesdays- census-income-and-poverty-release/ accessed May 16, 2014. -

Lecture Notes1 Mathematical Ecnomics

Lecture Notes1 Mathematical Ecnomics Guoqiang TIAN Department of Economics Texas A&M University College Station, Texas 77843 ([email protected]) This version: August, 2020 1The most materials of this lecture notes are drawn from Chiang’s classic textbook Fundamental Methods of Mathematical Economics, which are used for my teaching and con- venience of my students in class. Please not distribute it to any others. Contents 1 The Nature of Mathematical Economics 1 1.1 Economics and Mathematical Economics . 1 1.2 Advantages of Mathematical Approach . 3 2 Economic Models 5 2.1 Ingredients of a Mathematical Model . 5 2.2 The Real-Number System . 5 2.3 The Concept of Sets . 6 2.4 Relations and Functions . 9 2.5 Types of Function . 11 2.6 Functions of Two or More Independent Variables . 12 2.7 Levels of Generality . 13 3 Equilibrium Analysis in Economics 15 3.1 The Meaning of Equilibrium . 15 3.2 Partial Market Equilibrium - A Linear Model . 16 3.3 Partial Market Equilibrium - A Nonlinear Model . 18 3.4 General Market Equilibrium . 19 3.5 Equilibrium in National-Income Analysis . 23 4 Linear Models and Matrix Algebra 25 4.1 Matrix and Vectors . 26 i ii CONTENTS 4.2 Matrix Operations . 29 4.3 Linear Dependance of Vectors . 32 4.4 Commutative, Associative, and Distributive Laws . 33 4.5 Identity Matrices and Null Matrices . 34 4.6 Transposes and Inverses . 36 5 Linear Models and Matrix Algebra (Continued) 41 5.1 Conditions for Nonsingularity of a Matrix . 41 5.2 Test of Nonsingularity by Use of Determinant . -

Law-And-Political-Economy Framework: Beyond the Twentieth-Century Synthesis Abstract

JEDEDIAH BRITTON- PURDY, DAVID SINGH GREWAL, AMY KAPCZYNSKI & K. SABEEL RAHMAN Building a Law-and-Political-Economy Framework: Beyond the Twentieth-Century Synthesis abstract. We live in a time of interrelated crises. Economic inequality and precarity, and crises of democracy, climate change, and more raise significant challenges for legal scholarship and thought. “Neoliberal” premises undergird many fields of law and have helped authorize policies and practices that reaffirm the inequities of the current era. In particular, market efficiency, neu- trality, and formal equality have rendered key kinds of power invisible, and generated a skepticism of democratic politics. The result of these presumptions is what we call the “Twentieth-Century Synthesis”: a pervasive view of law that encases “the market” from claims of justice and conceals it from analyses of power. This Feature offers a framework for identifying and critiquing the Twentieth-Century Syn- thesis. This is also a framework for a new “law-and-political-economy approach” to legal scholar- ship. We hope to help amplify and catalyze scholarship and pedagogy that place themes of power, equality, and democracy at the center of legal scholarship. authors. The authors are, respectively, William S. Beinecke Professor of Law at Columbia Law School; Professor of Law at Berkeley Law School; Professor of Law at Yale Law School; and Associate Professor of Law at Brooklyn Law School and President, Demos. They are cofounders of the Law & Political Economy Project. The authors thank Anne Alstott, Jack Balkin, Jessica Bulman- Pozen, Corinne Blalock, Angela Harris, Luke Herrine, Doug Kysar, Zach Liscow, Daniel Markovits, Bill Novak, Frank Pasquale, Robert Post, David Pozen, Aziz Rana, Kate Redburn, Reva Siegel, Talha Syed, John Witt, and the participants of the January 2019 Law and Political Economy Work- shop at Yale Law School for their comments on drafts at many stages of the project. -

Post-Keynesian Economics

History and Methods of Post- Keynesian Macroeconomics Marc Lavoie University of Ottawa Outline • 1A. We set post-Keynesian economics within a set of multiple heterodox schools of thought, in opposition to mainstream schools. • 1B. We identify the main features (presuppositions) of heterodoxy, contrasting them to those of orthodoxy. • 2. We go over a brief history of post-Keynesian economics, in particular its founding institutional moments. • 3. We identify the additional features that characterize post- Keynesian economics relative to closely-related heterodox schools. • 4. We delineate the various streams of post-Keynesian economics: Fundamentalism, Kaleckian, Kaldorian, Sraffian, Institutionalist. • 5. We discuss the evolution of post-Keynesian economics, and some of its important works over the last 40 years. • 6. We mention some of the debates that have rocked post- Keynesian economics. PART I Heterodox schools Heterodox vs Orthodox economics •NON-ORTHODOX • ORTHODOX PARADIGM PARADIGM • DOMINANT PARADIGM • HETERODOX PARADIGM • THE MAINSTREAM • POST-CLASSICAL PARADIGM • NEOCLASSICAL ECONOMICS • RADICAL POLITICAL ECONOMY • REVIVAL OF POLITICAL ECONOMY Macro- economics Heterodox Neoclassical authors KEYNES school Cambridge Old Marxists Monetarists Keynesians Keynesians Radicals French Post- New New Regulation Keynesians Keynesians Classicals School Orthodox vs Heterodox economics • Post-Keynesian economics is one of many different heterodox schools of economics. • Heterodox economists are dissenters in economics. • Dissent is a broader -

Mathematical Economics - B.S

College of Mathematical Economics - B.S. Arts and Sciences The mathematical economics major offers students a degree program that combines College Requirements mathematics, statistics, and economics. In today’s increasingly complicated international I. Foreign Language (placement exam recommended) ........................................... 0-14 business world, a strong preparation in the fundamentals of both economics and II. Disciplinary Requirements mathematics is crucial to success. This degree program is designed to prepare a student a. Natural Science .............................................................................................3 to go directly into the business world with skills that are in high demand, or to go on b. Social Science (completed by Major Requirements) to graduate study in economics or finance. A degree in mathematical economics would, c. Humanities ....................................................................................................3 for example, prepare a student for the beginning of a career in operations research or III. Laboratory or Field Work........................................................................................1 actuarial science. IV. Electives ..................................................................................................................6 120 hours (minimum) College Requirement hours: ..........................................................13-27 Any student earning a Bachelor of Science (BS) degree must complete a minimum of 60 hours in natural, -

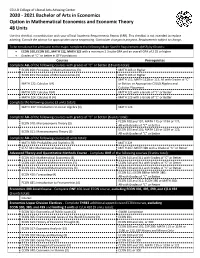

2020-2021 Bachelor of Arts in Economics Option in Mathematical

CSULB College of Liberal Arts Advising Center 2020 - 2021 Bachelor of Arts in Economics Option in Mathematical Economics and Economic Theory 48 Units Use this checklist in combination with your official Academic Requirements Report (ARR). This checklist is not intended to replace advising. Consult the advisor for appropriate course sequencing. Curriculum changes in progress. Requirements subject to change. To be considered for admission to the major, complete the following Major Specific Requirements (MSR) by 60 units: • ECON 100, ECON 101, MATH 122, MATH 123 with a minimum 2.3 suite GPA and an overall GPA of 2.25 or higher • Grades of “C” or better in GE Foundations Courses Prerequisites Complete ALL of the following courses with grades of “C” or better (18 units total): ECON 100: Principles of Macroeconomics (3) MATH 103 or Higher ECON 101: Principles of Microeconomics (3) MATH 103 or Higher MATH 111; MATH 112B or 113; All with Grades of “C” MATH 122: Calculus I (4) or Better; or Appropriate CSULB Algebra and Calculus Placement MATH 123: Calculus II (4) MATH 122 with a Grade of “C” or Better MATH 224: Calculus III (4) MATH 123 with a Grade of “C” or Better Complete the following course (3 units total): MATH 247: Introduction to Linear Algebra (3) MATH 123 Complete ALL of the following courses with grades of “C” or better (6 units total): ECON 100 and 101; MATH 115 or 119A or 122; ECON 310: Microeconomic Theory (3) All with Grades of “C” or Better ECON 100 and 101; MATH 115 or 119A or 122; ECON 311: Macroeconomic Theory (3) All with -

The Neoclassical Synthesis

Department of Economics- FEA/USP In Search of Lost Time: The Neoclassical Synthesis MICHEL DE VROEY PEDRO GARCIA DUARTE WORKING PAPER SERIES Nº 2012-07 DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS, FEA-USP WORKING PAPER Nº 2012-07 In Search of Lost Time: The Neoclassical Synthesis Michel De Vroey ([email protected]) Pedro Garcia Duarte ([email protected]) Abstract: Present day macroeconomics has been sometimes dubbed as the new neoclassical synthesis, suggesting that it constitutes a reincarnation of the neoclassical synthesis of the 1950s. This has prompted us to examine the contents of the ‘old’ and the ‘new’ neoclassical syntheses. Our main conclusion is that the latter bears little resemblance with the former. Additionally, we make three points: (a) from its origins with Paul Samuelson onward the neoclassical synthesis notion had no fixed content and we bring out four main distinct meanings; (b) its most cogent interpretation, defended e.g. by Solow and Mankiw, is a plea for a pluralistic macroeconomics, wherein short-period market non-clearing models would live side by side with long-period market-clearing models; (c) a distinction should be drawn between first and second generation new Keynesian economists as the former defend the old neoclassical synthesis while the latter, with their DSGE models, adhere to the Lucasian view that macroeconomics should be based on a single baseline model. Keywords: neoclassical synthesis; new neoclassical synthesis; DSGE models; Paul Samuelson; Robert Lucas JEL Codes: B22; B30; E12; E13 1 IN SEARCH OF LOST TIME: THE NEOCLASSICAL SYNTHESIS Michel De Vroey1 and Pedro Garcia Duarte2 Introduction Since its inception, macroeconomics has witnessed an alternation between phases of consensus and dissent. -

New Perspectives on the History of Political Economy Robert Fredona · Sophus A

New Perspectives on the History of Political Economy Robert Fredona · Sophus A. Reinert Editors New Perspectives on the History of Political Economy Editors Robert Fredona Sophus A. Reinert Harvard Business School Harvard Business School Boston, MA, USA Boston, MA, USA ISBN 978-3-319-58246-7 ISBN 978-3-319-58247-4 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-58247-4 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017943663 © Te Editor(s) (if applicable) and Te Author(s) 2018 Tis work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifcally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microflms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. Te use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specifc statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. Te publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. Te publisher remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional afliations. -

Political Economy Analysis for Development Effectiveness by Olivier Serrat

Knowledge September 2011 | 107 Solutions Political Economy Analysis for Development Effectiveness By Olivier Serrat Define:Political Economy Economics—the social science that deals with the production, Political economy distribution, and consumption of material wealth and with the embraces the complex theory and management of economic systems or economies1— political nature of was once called political economy.2 Anchored in moral decision making to philosophy, thence the art and science of government, this investigate how power articulated the belief in the 18th–19th centuries that political and authority affect considerations—and the interest groups that drive them— economic choices in have primacy in determining influence and thus economic a society. Political outcomes at (almost) any level of investigation. However, with the division of economics and political science into economy analysis distinct disciplines from the 1890s, neoclassical economists turned from analyses of offers no quick fixes power and authority to models that, inherently, remove much complexity from the issues but leads to smarter they look into.3 engagement. Today, political economists study interrelationships between political and economic institutions (or forces) and processes, which do not necessarily lead to optimal use of scarce resources.4 Refusing to eschew complexity, they appreciate politics as the sum 1 There is no universally accepted definition of economics. Two other characterizations that both place an accent on scarcity consider it the study of (i) the forces of supply and demand in the allocation of scarce resources, and (ii) individual and social behavior for the attainment and use of the material requisites of economic well-being as a relationship between given ends and scarce means that have alternative uses. -

The Rise and Fall of Walrasian General Equilibrium Theory: the Keynes Effect

The Rise and Fall of Walrasian General Equilibrium Theory: The Keynes Effect D. Wade Hands Department of Economics University of Puget Sound Tacoma, WA USA [email protected] Version 1.3 September 2009 15,246 Words This paper was initially presented at The First International Symposium on the History of Economic Thought “The Integration of Micro and Macroeconomics from a Historical Perspective,” University of São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil, August 3-5, 2009. Abstract: Two popular claims about mid-to-late twentieth century economics are that Walrasian ideas had a significant impact on the Keynesian macroeconomics that became dominant during the 1950s and 1060s, and that Arrow-Debreu Walrasian general equilibrium theory passed its zenith in microeconomics at some point during the 1980s. This paper does not challenge either of these standard interpretations of the history of modern economics. What the paper argues is that there are at least two very important relationships between Keynesian economics and Walrasian general equilibrium theory that have not generally been recognized within the literature. The first is that influence ran not only from Walrasian theory to Keynesian, but also from Keynesian theory to Walrasian. It was during the neoclassical synthesis that Walrasian economics emerged as the dominant form of microeconomics and I argue that its compatibility with Keynesian theory influenced certain aspects of its theoretical content and also contributed to its success. The second claim is that not only did Keynesian economics contribute to the rise Walrasian general equilibrium theory, it has also contributed to its decline during the last few decades. The features of Walrasian theory that are often suggested as its main failures – stability analysis and the Sonnenschein-Mantel-Debreu theorems on aggregate excess demand functions – can be traced directly to the features of the Walrasian model that connected it so neatly to Keynesian macroeconomics during the 1950s.