Economics and Neoliberalism 25/11/05

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lecture Notes1 Mathematical Ecnomics

Lecture Notes1 Mathematical Ecnomics Guoqiang TIAN Department of Economics Texas A&M University College Station, Texas 77843 ([email protected]) This version: August, 2020 1The most materials of this lecture notes are drawn from Chiang’s classic textbook Fundamental Methods of Mathematical Economics, which are used for my teaching and con- venience of my students in class. Please not distribute it to any others. Contents 1 The Nature of Mathematical Economics 1 1.1 Economics and Mathematical Economics . 1 1.2 Advantages of Mathematical Approach . 3 2 Economic Models 5 2.1 Ingredients of a Mathematical Model . 5 2.2 The Real-Number System . 5 2.3 The Concept of Sets . 6 2.4 Relations and Functions . 9 2.5 Types of Function . 11 2.6 Functions of Two or More Independent Variables . 12 2.7 Levels of Generality . 13 3 Equilibrium Analysis in Economics 15 3.1 The Meaning of Equilibrium . 15 3.2 Partial Market Equilibrium - A Linear Model . 16 3.3 Partial Market Equilibrium - A Nonlinear Model . 18 3.4 General Market Equilibrium . 19 3.5 Equilibrium in National-Income Analysis . 23 4 Linear Models and Matrix Algebra 25 4.1 Matrix and Vectors . 26 i ii CONTENTS 4.2 Matrix Operations . 29 4.3 Linear Dependance of Vectors . 32 4.4 Commutative, Associative, and Distributive Laws . 33 4.5 Identity Matrices and Null Matrices . 34 4.6 Transposes and Inverses . 36 5 Linear Models and Matrix Algebra (Continued) 41 5.1 Conditions for Nonsingularity of a Matrix . 41 5.2 Test of Nonsingularity by Use of Determinant . -

Supply and Demand Is Not a Neoclassical Concern

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Supply and Demand Is Not a Neoclassical Concern Lima, Gerson P. Macroambiente 3 March 2015 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/63135/ MPRA Paper No. 63135, posted 21 Mar 2015 13:54 UTC Supply and Demand Is Not a Neoclassical Concern Gerson P. Lima1 The present treatise is an attempt to present a modern version of old doctrines with the aid of the new work, and with reference to the new problems, of our own age (Marshall, 1890, Preface to the First Edition). 1. Introduction Many people are convinced that the contemporaneous mainstream economics is not qualified to explaining what is going on, to tame financial markets, to avoid crises and to provide a concrete solution to the poor and deteriorating situation of a large portion of the world population. Many economists, students, newspapers and informed people are asking for and expecting a new economics, a real world economic science. “The Keynes- inspired building-blocks are there. But it is admittedly a long way to go before the whole construction is in place. But the sooner we are intellectually honest and ready to admit that modern neoclassical macroeconomics and its microfoundationalist programme has come to way’s end – the sooner we can redirect our aspirations to more fruitful endeavours” (Syll, 2014, p. 28). Accordingly, this paper demonstrates that current mainstream monetarist economics cannot be science and proposes new approaches to economic theory and econometric method that after replication and enhancement may be a starting point for the creation of the real world economic theory. -

A Post-Keynesian Approach As an Alternative to Neoclassical in the Explanation of Monetary and Financial System

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Zachariadis, Savvas Article A Post-Keynesian approach as an alternative to neoclassical in the explanation of monetary and financial system Financial Studies Provided in Cooperation with: "Victor Slăvescu" Centre for Financial and Monetary Research, National Institute of Economic Research (INCE), Romanian Academy Suggested Citation: Zachariadis, Savvas (2020) : A Post-Keynesian approach as an alternative to neoclassical in the explanation of monetary and financial system, Financial Studies, ISSN 2066-6071, Romanian Academy, National Institute of Economic Research (INCE), "Victor Slăvescu" Centre for Financial and Monetary Research, Bucharest, Vol. 24, Iss. 1 (87), pp. 21-35 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/231693 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. -

Mathematical Economics - B.S

College of Mathematical Economics - B.S. Arts and Sciences The mathematical economics major offers students a degree program that combines College Requirements mathematics, statistics, and economics. In today’s increasingly complicated international I. Foreign Language (placement exam recommended) ........................................... 0-14 business world, a strong preparation in the fundamentals of both economics and II. Disciplinary Requirements mathematics is crucial to success. This degree program is designed to prepare a student a. Natural Science .............................................................................................3 to go directly into the business world with skills that are in high demand, or to go on b. Social Science (completed by Major Requirements) to graduate study in economics or finance. A degree in mathematical economics would, c. Humanities ....................................................................................................3 for example, prepare a student for the beginning of a career in operations research or III. Laboratory or Field Work........................................................................................1 actuarial science. IV. Electives ..................................................................................................................6 120 hours (minimum) College Requirement hours: ..........................................................13-27 Any student earning a Bachelor of Science (BS) degree must complete a minimum of 60 hours in natural, -

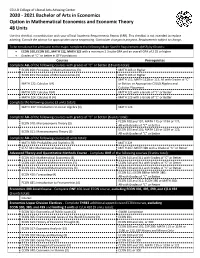

2020-2021 Bachelor of Arts in Economics Option in Mathematical

CSULB College of Liberal Arts Advising Center 2020 - 2021 Bachelor of Arts in Economics Option in Mathematical Economics and Economic Theory 48 Units Use this checklist in combination with your official Academic Requirements Report (ARR). This checklist is not intended to replace advising. Consult the advisor for appropriate course sequencing. Curriculum changes in progress. Requirements subject to change. To be considered for admission to the major, complete the following Major Specific Requirements (MSR) by 60 units: • ECON 100, ECON 101, MATH 122, MATH 123 with a minimum 2.3 suite GPA and an overall GPA of 2.25 or higher • Grades of “C” or better in GE Foundations Courses Prerequisites Complete ALL of the following courses with grades of “C” or better (18 units total): ECON 100: Principles of Macroeconomics (3) MATH 103 or Higher ECON 101: Principles of Microeconomics (3) MATH 103 or Higher MATH 111; MATH 112B or 113; All with Grades of “C” MATH 122: Calculus I (4) or Better; or Appropriate CSULB Algebra and Calculus Placement MATH 123: Calculus II (4) MATH 122 with a Grade of “C” or Better MATH 224: Calculus III (4) MATH 123 with a Grade of “C” or Better Complete the following course (3 units total): MATH 247: Introduction to Linear Algebra (3) MATH 123 Complete ALL of the following courses with grades of “C” or better (6 units total): ECON 100 and 101; MATH 115 or 119A or 122; ECON 310: Microeconomic Theory (3) All with Grades of “C” or Better ECON 100 and 101; MATH 115 or 119A or 122; ECON 311: Macroeconomic Theory (3) All with -

The Transformation of Macroeconomic Policy and Research

K4_40319_Prescott_358-395 05-08-18 11.41 Sida 370 THE TRANSFORMATION OF MACROECONOMIC POLICY AND RESEARCH Prize Lecture, December 8, 2004 by Edward C. Prescott* Arizona State University, Tempe, and Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA. 1. INTRODUCTION What I am going to describe for you is a revolution in macroeconomics, a transformation in methodology that has reshaped how we conduct our science. Prior to the transformation, macroeconomics was largely separate from the rest of economics. Indeed, some considered the study of macroeconomics fundamentally different and thought there was no hope of integrating macroeconomics with the rest of economics, that is, with neoclassical economics. Others held the view that neoclassical foundations for the empirically deter- mined macro relations would in time be developed. Neither view proved correct. Finn Kydland and I have been lucky to be a part of this revolution, and my address will focus heavily on our role in advancing this transformation. Now, all stories about transformation have three essential parts: the time prior to the key change, the transformative era, and the new period that has been impacted by the change. And that is the story I am going to tell: how macro- economic policy and research changed as the result of the transformation of macroeconomics from constructing a system of equations of the national accounts to an investigation of dynamic stochastic economies. Macroeconomics has progressed beyond the stage of searching for a theory to the stage of deriving the implications of theory. In this way, macroeconomics has become like the natural sciences. Unlike the natural sciences, though, macroeconomics involves people making decisions based upon what they think will happen, and what will happen depends upon what decisions they make. -

The Rise and Fall of Walrasian General Equilibrium Theory: the Keynes Effect

The Rise and Fall of Walrasian General Equilibrium Theory: The Keynes Effect D. Wade Hands Department of Economics University of Puget Sound Tacoma, WA USA [email protected] Version 1.3 September 2009 15,246 Words This paper was initially presented at The First International Symposium on the History of Economic Thought “The Integration of Micro and Macroeconomics from a Historical Perspective,” University of São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil, August 3-5, 2009. Abstract: Two popular claims about mid-to-late twentieth century economics are that Walrasian ideas had a significant impact on the Keynesian macroeconomics that became dominant during the 1950s and 1060s, and that Arrow-Debreu Walrasian general equilibrium theory passed its zenith in microeconomics at some point during the 1980s. This paper does not challenge either of these standard interpretations of the history of modern economics. What the paper argues is that there are at least two very important relationships between Keynesian economics and Walrasian general equilibrium theory that have not generally been recognized within the literature. The first is that influence ran not only from Walrasian theory to Keynesian, but also from Keynesian theory to Walrasian. It was during the neoclassical synthesis that Walrasian economics emerged as the dominant form of microeconomics and I argue that its compatibility with Keynesian theory influenced certain aspects of its theoretical content and also contributed to its success. The second claim is that not only did Keynesian economics contribute to the rise Walrasian general equilibrium theory, it has also contributed to its decline during the last few decades. The features of Walrasian theory that are often suggested as its main failures – stability analysis and the Sonnenschein-Mantel-Debreu theorems on aggregate excess demand functions – can be traced directly to the features of the Walrasian model that connected it so neatly to Keynesian macroeconomics during the 1950s. -

Money As 'Universal Equivalent' and Its Origins in Commodity Exchange

MONEY AS ‘UNIVERSAL EQUIVALENT’ AND ITS ORIGIN IN COMMODITY EXCHANGE COSTAS LAPAVITSAS DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS SCHOOL OF ORIENTAL AND AFRICAN STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF LONDON [email protected] MAY 2003 1 1.Introduction The debate between Zelizer (2000) and Fine and Lapavitsas (2000) in the pages of Economy and Society refers to the conceptualisation of money. Zelizer rejects the theorising of money by neoclassical economics (and some sociology), and claims that the concept of ‘money in general’ is invalid. Fine and Lapavitsas also criticise the neoclassical treatment of money but argue, from a Marxist perspective, that ‘money in general’ remains essential for social science. Intervening, Ingham (2001) finds both sides confused and in need of ‘untangling’. It is worth stressing that, despite appearing to be equally critical of both sides, Ingham (2001: 305) ‘strongly agrees’ with Fine and Lapavitsas on the main issue in contention, and defends the importance of a theory of ‘money in general’. However, he sharply criticises Fine and Lapavitsas for drawing on Marx’s work, which he considers incapable of supporting a theory of ‘money in general’. Complicating things further, Ingham (2001: 305) also declares himself ‘at odds with Fine and Lapavitsas’s interpretation of Marx’s conception of money’. For Ingham, in short, Fine and Lapavitsas are right to stress the importance of ‘money in general’ but wrong to rely on Marx, whom they misinterpret to boot. Responding to these charges is awkward since, on the one hand, Ingham concurs with the main thrust of Fine and Lapavitsas and, on the other, there is little to be gained from contesting what Marx ‘really said’ on the issue of money. -

Nine Lives of Neoliberalism

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Plehwe, Dieter (Ed.); Slobodian, Quinn (Ed.); Mirowski, Philip (Ed.) Book — Published Version Nine Lives of Neoliberalism Provided in Cooperation with: WZB Berlin Social Science Center Suggested Citation: Plehwe, Dieter (Ed.); Slobodian, Quinn (Ed.); Mirowski, Philip (Ed.) (2020) : Nine Lives of Neoliberalism, ISBN 978-1-78873-255-0, Verso, London, New York, NY, https://www.versobooks.com/books/3075-nine-lives-of-neoliberalism This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/215796 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative -

Schools of Economic Thought (Pdf)

SCHOOLS OF ECONOMIC THOUGHT A BRIEF HISTORY OF ECONOMICS This isn't really essential to know, but may satisfy the curiosity of many. Mercantilism Economics is said to begin with Adam Smith in 1776. Prior to that, nobody thought of economics, or markets, as an object of study. It is not that they didn't pay attention to economic matters, it is simply that they didn't think of it in any systematic or coherent manner. It was all just off-the-cuff intuition and policy proposals by a myriad of merchants, government officials & journalists, principally in Britain. It is common to denote the period before 1776 as "Mercantilism". It wasn't a coherent school of thought, but a hodge-podge of varying ideas about improving tax revenues, the value & movements of gold and how nations competed for international commerce & colonies. Mostly protectionist, 'war-minded', and all haphazardly argued. (the principal features of the Mercantilist school are discussed in our "Gains from Trade" handout). There was some opposition to Mercantilist doctrines, notably among French and Scottish thinkers (e.g. Pierre de Boisguilbert, Francois Quesnay, Jacques Turgot and David Hume) Classical School The Enlightenment era (mid-1700s) in Europe brought a new spirit of scientific inquiry. Thinkers began looking to apply scientific principles not only to the physical world, but also to human society. In the same spirit that Sir Isaac Newton 'discovered' the "law of gravity" to explain the interaction of natural forces and decipher how the physical world operates, Enlightenment thinkers began trying to discover the "laws" of human interaction, to explain how human society operates. -

Unemployment Did Not Rise During the Great Depression—Rather, People Took Long Vacations

Working Paper No. 652 The Dismal State of Macroeconomics and the Opportunity for a New Beginning by L. Randall Wray Levy Economics Institute of Bard College March 2011 The Levy Economics Institute Working Paper Collection presents research in progress by Levy Institute scholars and conference participants. The purpose of the series is to disseminate ideas to and elicit comments from academics and professionals. Levy Economics Institute of Bard College, founded in 1986, is a nonprofit, nonpartisan, independently funded research organization devoted to public service. Through scholarship and economic research it generates viable, effective public policy responses to important economic problems that profoundly affect the quality of life in the United States and abroad. Levy Economics Institute P.O. Box 5000 Annandale-on-Hudson, NY 12504-5000 http://www.levyinstitute.org Copyright © Levy Economics Institute 2011 All rights reserved ABSTRACT The Queen of England famously asked her economic advisers why none of them had seen “it” (the global financial crisis) coming. Obviously, the answer is complex, but it must include reference to the evolution of macroeconomic theory over the postwar period— from the “Age of Keynes,” through the Friedmanian era and the return of Neoclassical economics in a particularly extreme form, and, finally, on to the New Monetary Consensus, with a new version of fine-tuning. The story cannot leave out the parallel developments in finance theory—with its efficient markets hypothesis—and in approaches to regulation and supervision of financial institutions. This paper critically examines these developments and returns to the earlier Keynesian tradition to see what was left out of postwar macro. -

Econ5153 Mathematical Economics

ECON5153 MATHEMATICAL ECONOMICS University of Oklahoma, Fall 2014 Tuesday and Thursday, 9-10:15am, Cate Center CCD1 338 Instructor: Qihong Liu Office: CCD1 426 Phone: 325-5846 E-mail: [email protected] Office Hours: Tuesday and Thursday, 1:30-2:30pm, and by appointment Course Description This is the first course in the graduate Mathematical Economics/Econometrics sequence. The objective of this course is to acquaint the students with the fundamental mathematical techniques used in modern economics, including Matrix Algebra, Optimization and Dynam- ics. Upon completion of the course students will be able to set up and analytically solve constrained and unconstrained optimization problems. The students will also be able to solve linear difference equations and differential equations. Textbooks Required: Simon and Blume: Mathematics for Economists, W.W.Norton, 1994. Other useful books available on reserve at Bizzell: Chiang and Wainwright: Fundamental Methods of Mathematical Economics, McGraw-Hill, Fourth Edition, 2005. Darrell A. Turkington: Mathematical Tools for Economics, Blackwell Publishing, 2007. Avinash Dixit: Optimization in Economic Theory, Oxford University Press, Second Edition, 1990. Michael D. Intriligator: Mathematical Optimization and Economic Theory, Prentice-Hall, 1971. Assessment Grades are based on homework (15%), class participation (10%), two midterm exams (20% each) and final exam (35%). You are encouraged to form study groups to discuss homework and lecture materials. All exams will be in closed-book forms. Problem Sets Several problem sets will be assigned during the semester. You will have at least one week to complete each assignment. Late homework will not be accepted. You are allowed to work 1 with other students in this class on the problem sets, but each student must write his or her own answers.