The Ideology of Mathematical Economics – a Reply to Tony Lawson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Irrelevance and Ideology: a Comment on Tony Lawson's Book Reorienting Economics

Irrelevance and Ideology A comment on Tony Lawson’s book Reorienting Economics Published in Post-autistic economics review, issue no. 29, December 2004 There are plenty of interesting ideas in Lawson‟s book about how economic theory and practice need to be “reoriented”. I agree with him that economics must start from observation of the world where we live. I must say, however, that I do not see why Lawson needs the special word “ontology” to designate an “enquiry into (or a theory of) the nature of being or existence” (p. xv). Nor am I convinced by his “evolutionary explanation” – in Darwinian terms – of the “mathematising tendency” in economics (Chapter 10)1. But I do not want to discuss these complex subjects here. I am only going to consider Lawson‟s main criticism of neoclassical economics: its “lack of realism”. I think that it is not the appropriate objection: all theories lack realism, as they take into consideration only some aspects of reality. Everyone agrees on this, even neoclassical economists. The real problem with neoclassical theory is not its‟ “lack of realism” but the “ideology” (a word Lawson never uses) that it smuggles in and carries with it. Lack of realism and homo oeconomicus If economics needs to be “reoriented”, it is because its present orientation is wrong. What precisely is wrong with its orientation? If you read Lawson‟s book, it is wrong partly because of the assumption about man that it adopts. Man is assumed to be “rational”, “omniscient”, “selfish without limit” and so on. For example, in the section called “Fictions”, in the first chapter about modern economics, Lawson writes: Assumptions abound even to the effect that individuals possess perfect foresight (or, only slightly weaker, have rational expectations), or are selfish without limit, or are omniscient, or live for ever (p. -

Lecture Notes1 Mathematical Ecnomics

Lecture Notes1 Mathematical Ecnomics Guoqiang TIAN Department of Economics Texas A&M University College Station, Texas 77843 ([email protected]) This version: August, 2020 1The most materials of this lecture notes are drawn from Chiang’s classic textbook Fundamental Methods of Mathematical Economics, which are used for my teaching and con- venience of my students in class. Please not distribute it to any others. Contents 1 The Nature of Mathematical Economics 1 1.1 Economics and Mathematical Economics . 1 1.2 Advantages of Mathematical Approach . 3 2 Economic Models 5 2.1 Ingredients of a Mathematical Model . 5 2.2 The Real-Number System . 5 2.3 The Concept of Sets . 6 2.4 Relations and Functions . 9 2.5 Types of Function . 11 2.6 Functions of Two or More Independent Variables . 12 2.7 Levels of Generality . 13 3 Equilibrium Analysis in Economics 15 3.1 The Meaning of Equilibrium . 15 3.2 Partial Market Equilibrium - A Linear Model . 16 3.3 Partial Market Equilibrium - A Nonlinear Model . 18 3.4 General Market Equilibrium . 19 3.5 Equilibrium in National-Income Analysis . 23 4 Linear Models and Matrix Algebra 25 4.1 Matrix and Vectors . 26 i ii CONTENTS 4.2 Matrix Operations . 29 4.3 Linear Dependance of Vectors . 32 4.4 Commutative, Associative, and Distributive Laws . 33 4.5 Identity Matrices and Null Matrices . 34 4.6 Transposes and Inverses . 36 5 Linear Models and Matrix Algebra (Continued) 41 5.1 Conditions for Nonsingularity of a Matrix . 41 5.2 Test of Nonsingularity by Use of Determinant . -

Mathematical Economics - B.S

College of Mathematical Economics - B.S. Arts and Sciences The mathematical economics major offers students a degree program that combines College Requirements mathematics, statistics, and economics. In today’s increasingly complicated international I. Foreign Language (placement exam recommended) ........................................... 0-14 business world, a strong preparation in the fundamentals of both economics and II. Disciplinary Requirements mathematics is crucial to success. This degree program is designed to prepare a student a. Natural Science .............................................................................................3 to go directly into the business world with skills that are in high demand, or to go on b. Social Science (completed by Major Requirements) to graduate study in economics or finance. A degree in mathematical economics would, c. Humanities ....................................................................................................3 for example, prepare a student for the beginning of a career in operations research or III. Laboratory or Field Work........................................................................................1 actuarial science. IV. Electives ..................................................................................................................6 120 hours (minimum) College Requirement hours: ..........................................................13-27 Any student earning a Bachelor of Science (BS) degree must complete a minimum of 60 hours in natural, -

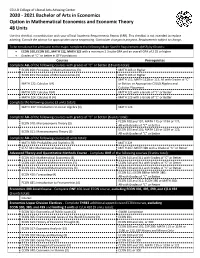

2020-2021 Bachelor of Arts in Economics Option in Mathematical

CSULB College of Liberal Arts Advising Center 2020 - 2021 Bachelor of Arts in Economics Option in Mathematical Economics and Economic Theory 48 Units Use this checklist in combination with your official Academic Requirements Report (ARR). This checklist is not intended to replace advising. Consult the advisor for appropriate course sequencing. Curriculum changes in progress. Requirements subject to change. To be considered for admission to the major, complete the following Major Specific Requirements (MSR) by 60 units: • ECON 100, ECON 101, MATH 122, MATH 123 with a minimum 2.3 suite GPA and an overall GPA of 2.25 or higher • Grades of “C” or better in GE Foundations Courses Prerequisites Complete ALL of the following courses with grades of “C” or better (18 units total): ECON 100: Principles of Macroeconomics (3) MATH 103 or Higher ECON 101: Principles of Microeconomics (3) MATH 103 or Higher MATH 111; MATH 112B or 113; All with Grades of “C” MATH 122: Calculus I (4) or Better; or Appropriate CSULB Algebra and Calculus Placement MATH 123: Calculus II (4) MATH 122 with a Grade of “C” or Better MATH 224: Calculus III (4) MATH 123 with a Grade of “C” or Better Complete the following course (3 units total): MATH 247: Introduction to Linear Algebra (3) MATH 123 Complete ALL of the following courses with grades of “C” or better (6 units total): ECON 100 and 101; MATH 115 or 119A or 122; ECON 310: Microeconomic Theory (3) All with Grades of “C” or Better ECON 100 and 101; MATH 115 or 119A or 122; ECON 311: Macroeconomic Theory (3) All with -

Critique of Tony Lawson on Neoclassical Economics Victor Aguilar

Critique of Tony Lawson on Neoclassical Economics Victor Aguilar www.axiomaticeconomics.com Abstract I review Tony Lawson’s paper, What is this ‘school’ called neoclassical economics? Varoufakis and Arnsperger also wrote a paper asking, “What is Neoclassical Economics?” I review it here. They define neoclassical as methodological individualism, instrumentalism and equilibriation, which Lawson explicitly rejects, writing, “the core feature of neoclassical economics is adherence not to any particular substantive features but to deductivism itself in a situation where the general open-processual nature of social reality is widely recognised at some level.” Conflating Taxonomy and Deductive Logic Unlike Mark Buchanan, who has meteorologist envy, Tony Lawson has biologist envy. Who says pluralism is just an excuse for the World Economics Association to blacklist mathematicians? These pluralists are all unique! Buchanan (2013, p. 206) writes: The British Meteorological Office, for example, then [1900] maintained a huge and ever-growing index of weather maps recording air pressures, humidity, and other atmospheric variables at stations scattered around the country, day by day, stretching well into the past. It was a history of the weather, and meteorologists consulted it as a “look it up” guide to what should happen next. The idea was simple. Whatever the current weather, scientists would scour the index of past weather looking for a similar pattern. Weather forecasting in those days was just a catalog of proverbs: red sky at night, sailor's delight; red sky in the morning, sailors take warning; rainbow in the morning gives you fair warning; halo around the sun or moon, rain or snow soon; etc. -

Essential Readings

CRITICAL REALISM Since the publication of Roy Bhaskar's A Realist Theory 0/ Science in 1975, critical realism has emerged as one ofthe most powerfulnew directions in the philosophy of science and social science, offering a real alternative to both positivism and post modernism. This reader is designed to make accessible in one volume, to lay person and academic, student and teacher alike, key readings to stimulate debate about and within critical realism. The four parts of the reader correspond to four parts of the writings of Roy Bhaskar: • part one explores the transcendental realist philosophy of science elaborated in A Realist Theory o/ Science • the second section examines Bhaskar's critical naturalist philosophy of social science • part three is devoted to the theory of explanatory critique, which is central to critical realism • the final part is devoted to the theme of dialectic, which is central to Bhaskar's most recent writings The volume includes extracts from Bhaskar's most important books, as well as selections from all of the other most important contributors to the critical realist programme. The volume also includes both a general introduction and original introductions to each section. CRITICAL REALISM Essential Readings Edited by Margaret Arche� Roy Bhaska� Andrew Collie� Tony Lawson and Alan Norrie London and New York First published 1998 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 29 West 35th Street, New Yo rk, NY 10001 © 1998 Selection and editorial matter Margaret Archer, Roy Bhaskar, Andrew Collier, To ny Lawson and Alan Norrie Typeset in Garamond by RefineCatch Limited, Bungay, Suffolk Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ International Ltd, Padstow, Cornwall All rights reserved. -

7 Gender and Social Change Tony Lawson

7 Gender and social change tony lawson ow in the context of the currently develop- ing global order (and consequent ever-changing local H political frameworks) might feminists most sensibly seek to transform the gendered features of society in such a manner as to facilitate a less discriminating scenario than is currently in evidence? This is a question that motivates much of the thinking behind this book. But posing it carries certain presuppositions. In particular it takes for granted the notion that gender is a meaningful as well as useful category of analysis. And it presumes, too, that, whatever the socio-political context, it is always feasible to identify some forms of emancipatory practice, at least with respect to gender discrimination. Or at least there is an assumption that such emancipatory practice is not ruled out in principle. Both sets of presuppositions have been found to be problematic. Specifically, various feminist theorists hold that there are conceptual and political difficulties to making use of the category of gender in social theorising (see e.g. Bordo 1993; Spelman 1990). And the reasoning behind such assessments tends in its turn to be destabilising of the goal of emancipatory practice. In this chapter I focus on these latter concerns rather than the more specific question posed at the outset. For unless the noted difficulties can somehow be resolved any further questioning of appropriate local and global strategies appears to beg too many issues. I shall suggest that the difficulties in question can indeed be resolved, but that this necessitates a turn to explicit and systematic ontological elaboration, a practice that feminists have tended to avoid (see Lawson 2003), but which, I want to suggest, needs now to be (re)introduced to the study and politics of gender inequality. -

The Rise and Fall of Walrasian General Equilibrium Theory: the Keynes Effect

The Rise and Fall of Walrasian General Equilibrium Theory: The Keynes Effect D. Wade Hands Department of Economics University of Puget Sound Tacoma, WA USA [email protected] Version 1.3 September 2009 15,246 Words This paper was initially presented at The First International Symposium on the History of Economic Thought “The Integration of Micro and Macroeconomics from a Historical Perspective,” University of São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil, August 3-5, 2009. Abstract: Two popular claims about mid-to-late twentieth century economics are that Walrasian ideas had a significant impact on the Keynesian macroeconomics that became dominant during the 1950s and 1060s, and that Arrow-Debreu Walrasian general equilibrium theory passed its zenith in microeconomics at some point during the 1980s. This paper does not challenge either of these standard interpretations of the history of modern economics. What the paper argues is that there are at least two very important relationships between Keynesian economics and Walrasian general equilibrium theory that have not generally been recognized within the literature. The first is that influence ran not only from Walrasian theory to Keynesian, but also from Keynesian theory to Walrasian. It was during the neoclassical synthesis that Walrasian economics emerged as the dominant form of microeconomics and I argue that its compatibility with Keynesian theory influenced certain aspects of its theoretical content and also contributed to its success. The second claim is that not only did Keynesian economics contribute to the rise Walrasian general equilibrium theory, it has also contributed to its decline during the last few decades. The features of Walrasian theory that are often suggested as its main failures – stability analysis and the Sonnenschein-Mantel-Debreu theorems on aggregate excess demand functions – can be traced directly to the features of the Walrasian model that connected it so neatly to Keynesian macroeconomics during the 1950s. -

Nine Lives of Neoliberalism

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Plehwe, Dieter (Ed.); Slobodian, Quinn (Ed.); Mirowski, Philip (Ed.) Book — Published Version Nine Lives of Neoliberalism Provided in Cooperation with: WZB Berlin Social Science Center Suggested Citation: Plehwe, Dieter (Ed.); Slobodian, Quinn (Ed.); Mirowski, Philip (Ed.) (2020) : Nine Lives of Neoliberalism, ISBN 978-1-78873-255-0, Verso, London, New York, NY, https://www.versobooks.com/books/3075-nine-lives-of-neoliberalism This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/215796 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative -

Econ5153 Mathematical Economics

ECON5153 MATHEMATICAL ECONOMICS University of Oklahoma, Fall 2014 Tuesday and Thursday, 9-10:15am, Cate Center CCD1 338 Instructor: Qihong Liu Office: CCD1 426 Phone: 325-5846 E-mail: [email protected] Office Hours: Tuesday and Thursday, 1:30-2:30pm, and by appointment Course Description This is the first course in the graduate Mathematical Economics/Econometrics sequence. The objective of this course is to acquaint the students with the fundamental mathematical techniques used in modern economics, including Matrix Algebra, Optimization and Dynam- ics. Upon completion of the course students will be able to set up and analytically solve constrained and unconstrained optimization problems. The students will also be able to solve linear difference equations and differential equations. Textbooks Required: Simon and Blume: Mathematics for Economists, W.W.Norton, 1994. Other useful books available on reserve at Bizzell: Chiang and Wainwright: Fundamental Methods of Mathematical Economics, McGraw-Hill, Fourth Edition, 2005. Darrell A. Turkington: Mathematical Tools for Economics, Blackwell Publishing, 2007. Avinash Dixit: Optimization in Economic Theory, Oxford University Press, Second Edition, 1990. Michael D. Intriligator: Mathematical Optimization and Economic Theory, Prentice-Hall, 1971. Assessment Grades are based on homework (15%), class participation (10%), two midterm exams (20% each) and final exam (35%). You are encouraged to form study groups to discuss homework and lecture materials. All exams will be in closed-book forms. Problem Sets Several problem sets will be assigned during the semester. You will have at least one week to complete each assignment. Late homework will not be accepted. You are allowed to work 1 with other students in this class on the problem sets, but each student must write his or her own answers. -

Paul Samuelson's Ways to Macroeconomic Dynamics

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Boianovsky, Mauro Working Paper Paul Samuelson's ways to macroeconomic dynamics CHOPE Working Paper, No. 2019-08 Provided in Cooperation with: Center for the History of Political Economy at Duke University Suggested Citation: Boianovsky, Mauro (2019) : Paul Samuelson's ways to macroeconomic dynamics, CHOPE Working Paper, No. 2019-08, Duke University, Center for the History of Political Economy (CHOPE), Durham, NC This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/196831 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu Paul Samuelson’s Ways to Macroeconomic Dynamics by Mauro Boianovsky CHOPE Working Paper No. 2019-08 May 2019 Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3386201 1 Paul Samuelson’s ways to macroeconomic dynamics Mauro Boianovsky (Universidade de Brasilia) [email protected] First preliminary draft. -

Roundtable: Tony Lawson's Reorienting Economics

Journal of Economic Methodology 11:3, 329–340 September 2004 Roundtable: Tony Lawson’s Reorienting Economics Reorienting Economics: On heterodox economics, themata and the use of mathematics in economics Tony Lawson It is always a pleasure to have a piece of research reviewed. It is especially so when, as here, the reviewers offer their assessments, including criticisms, in a constructive and generous spirit. I provide brief reactions to the reviews, addressing them in the order in which they appear above. There is in each review much with which I agree, as well as critical suggestions on which I want to reflect more. Although all the reviewers express some agreement with Reorienting Economics, each concentrates her or his focus mostly (though not wholly) where differences (or likely differences) between us seem to remain. In responding I will do the same. 1 DOW Sheila Dow starts with an accurate summary of my purpose with Reorient- ing Economics. Central to the latter is my arguing for a reorientation of social theory in general, and of economics in particular, towards an explicit, systematic and sustained concern with ontology. Dow seems to accept the need for this. But she believes there is a problem with an aspect of my argument, or, more specifically, with an implication I draw from my own ontological analyses, concerning the possibilities for modern economics. The issue in contention is, or follows from, the manner in which I character- ize the various heterodox traditions. An essential component of my argument is that mainstream economists, by restricting themselves to methods of mathematical-deductivist modelling, are forced to theorise worlds of isolated atoms.