Transactions of the Norfolk and Norwich Naturalists' Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

County Town Title Film/Fiche # Item # Norfolk Benefices, List Of

County Town Title Film/Fiche # Item # Norfolk Benefices, List of 1471412 It 44 Norfolk Census 1851 Index 6115160 Norfolk Church Records 1725-1812 1526807 It 1 Norfolk Marriage Allegations Index 1811-1825 375230 Norfolk Marriage Allegations Index 1825-1839 375231 Norfolk Marriage Allegations Index 1839-1859 375232 Norfolk Marriage Bonds 1715-1734 1596461 Norfolk Marriage Bonds 1734-1749 1596462 Norfolk Marriage Bonds 1770-1774 1596563 Norfolk Marriage Bonds 1774-1781 1596564 Norfolk Marriage Bonds 1790-1797 1596566 Norfolk Marriage Bonds 1798-1803 1596567 Norfolk Marriage Bonds 1812-1819 1596597 Norfolk Marriages Parish Registers 1539-1812 496683 It 2 Norfolk Probate Inventories Index 1674-1825 1471414 It 17-20 Norfolk Tax Assessments 1692-1806 1471412 It 30-43 Norfolk Wills V.101 1854-1857 167184 Norfolk Alburgh Parish Register Extracts 1538-1715 894712 It 5 Norfolk Alby Parish Records 1600-1812 1526778 It 15 Norfolk Aldeby Church Records 1725-1812 1526786 It 6 Norfolk Alethorpe Census 1841 438859 Norfolk Arminghall Census 1841 438862 Norfolk Ashby Church Records 1725-1812 1526786 It 7 Norfolk Ashby Parish Register Extracts 1646 894712 It 5 Norfolk Ashwell-Thorpe Census 1841 438851 Norfolk Aslacton Census 1841 438851 Norfolk Baconsthorpe Parish Register Extracts 1676-1770 894712 It 6 Norfolk Bagthorpe Census 1841 438859 Norfolk Bale Census 1841 438862 Norfolk Bale Parish Register Extracts 1538-1716 894712 It 6 Norfolk Barmer Census 1841 438859 Norfolk Barney Census 1841 438859 Norfolk Barton-Bendish Church Records 1725-1812 1526807 It -

Parish Registers and Transcripts in the Norfolk Record Office

Parish Registers and Transcripts in the Norfolk Record Office This list summarises the Norfolk Record Office’s (NRO’s) holdings of parish (Church of England) registers and of transcripts and other copies of them. Parish Registers The NRO holds registers of baptisms, marriages, burials and banns of marriage for most parishes in the Diocese of Norwich (including Suffolk parishes in and near Lowestoft in the deanery of Lothingland) and part of the Diocese of Ely in south-west Norfolk (parishes in the deanery of Fincham and Feltwell). Some Norfolk parish records remain in the churches, especially more recent registers, which may be still in use. In the extreme west of the county, records for parishes in the deanery of Wisbech Lynn Marshland are deposited in the Wisbech and Fenland Museum, whilst Welney parish records are at the Cambridgeshire Record Office. The covering dates of registers in the following list do not conceal any gaps of more than ten years; for the populous urban parishes (such as Great Yarmouth) smaller gaps are indicated. Whenever microfiche or microfilm copies are available they must be used in place of the original registers, some of which are unfit for production. A few parish registers have been digitally photographed and the images are available on computers in the NRO's searchroom. The digital images were produced as a result of partnership projects with other groups and organizations, so we are not able to supply copies of whole registers (either as hard copies or on CD or in any other digital format), although in most cases we have permission to provide printout copies of individual entries. -

Our Special 50Th Birthday Issue

FREE CoSuaffoslk t & Heaths Spring/Summer 2020 Our Special 50th Birthday Issue In our 50th birthday issue Jules Pretty, author and professor, talks about how designation helps focus conservation and his hopes for the next 50 years, page 9 e g a P e k i M © Where will you explore? What will you do to conserve our Art and culture are great ways to Be inspired by our anniversary landscape? Join a community beach inspire us to conserve our landscape, 50 @ 50 places to see and clean or work party! See pages 7, and we have the best landscape for things to do, centre pages 17, 18 for ideas doing this! See pages 15, 18, 21, 22 www.suffolkcoastandheaths.org Suffolk Coast & Heaths Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty • 1 Your AONB ur national Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty are terms of natural beauty, quality of life for residents and its A Message from going to have a year to remember and it will be locally associated tourism industry. See articles on page 4. Osignificant too! In December 2019 the Chair’s from all the AONBs collectively committed the national network to The National Association for AONBs has recently published a Our Chair the Colchester Declaration for Nature, and we will all play position statement relating to housing, and the Government has our part in nature recovery, addressing the twin issues of updated its advice on how to consider light in the planning wildlife decline and climate change. Suffolk Coast & Heaths system. AONB Partnership will write a bespoke Nature Recovery Plan and actions, and specifically champion a species to support We also look forward (if that’s the right term, as we say its recovery. -

Carbon Emissions Study in the European Straits of the PASSAGE Project

Carbon emissions study in the European Straits of the PASSAGE project Final Report Prepared for Département du Pas-de-Calais and the partners of the PASSAGE Project April 2018 Document information CLIENT Département du Pas-de-Calais - PASSAGE Project REPORT TITLE Final report PROJECT NAME Carbon emissions study in the European Straits of the PASSAGE project DATE April 2018 PROJECT TEAM I Care & Consult Mr. Léo Genin Ms. Lucie Mouthuy KEY CONTACTS Léo Genin +33 (0)4 72 12 12 35 [email protected] DISCLAIMER The project team does not accept any liability for any direct or indirect damage resulting from the use of this report or its content. This report contains the results of research by the authors and is not to be perceived as the opinion of the partners of the PASSAGE Project. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS We would like to thank all the partners of the PASSAGE Project that contributed to the carbon emissions study. Carbon emissions study in the European Straits of the PASSAGE project Final Report 2 Table of contents INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................................... 5 1. Context of this study ................................................................................................................... 5 2. Objectives .................................................................................................................................... 6 3. Overview of the general approach ............................................................................................. -

Traces Under Water Exploring and Protecting the Cultural Heritage in the North Sea and Baltic Sea

2019 | Discussion No. 23 Traces under water Exploring and protecting the cultural heritage in the North Sea and Baltic Sea Christian Anton | Mike Belasus | Roland Bernecker Constanze Breuer | Hauke Jöns | Sabine von Schorlemer Publication details Publisher Deutsche Akademie der Naturforscher Leopoldina e. V. – German National Academy of Sciences – President: Prof. Dr. Jörg Hacker Jägerberg 1, D-06108 Halle (Saale) Editorial office Christian Anton, Constanze Breuer & Johannes Mengel, German National Academy of Sciences Leopoldina Copy deadline November 2019 Contact [email protected] Image design Sarah Katharina Heuzeroth, Hamburg Cover image Sarah Katharina Heuzeroth, Hamburg Fictitious representation of the discovery of a hand wedge using a submersible: The exploration of prehistoric landscapes in the sediments of the North Sea and Baltic Sea could one day lead to the discovery of traces of human activity or campsites. Translation GlobalSprachTeam ‒ Sassenberg+Kollegen, Berlin Proofreading Alan Frostick, Frostick & Peters, Hamburg Typesetting unicommunication.de, Berlin Print druckhaus köthen GmbH & Co. KG ISBN 978-3-8047-4070-9 Bibliographic Information of the German National Library The German National Library lists this publication in the German National Bibliography. Detailed bibliographic data are available online at http://dnb.d-nb.de. Suggested citation Anton, C., Belasus, M., Bernecker, R., Breuer, C., Jöns, H., & Schorlemer, S. v. (2019). Traces under water. Exploring and protecting the cultural heritage in the North Sea and Baltic Sea. Halle (Saale): German National Academy of Sciences Leopoldina. Traces under water Exploring and protecting the cultural heritage in the North Sea and Baltic Sea Christian Anton | Mike Belasus | Roland Bernecker Constanze Breuer | Hauke Jöns | Sabine von Schorlemer The Leopoldina Discussions series publishes contributions by the authors named. -

Transactions of the Norfolk and Norwich Naturalists' Society

: ; TRANSACTIONS OF THE IlutTnlk anti BntTtfick SOCIETY Presented to the Members for - 1882 83 . A OL. III. —Part iv. Itorbidi PRINTED BY FLETCHER AND SON. 1383 . OFFICERS FOR 1882-83. resilient. MR. H. D. GELDART. fEr^rrstornt. MR. J. II. GURNEY, Jun., F.Z.S. Ficc^Jrrsiticnts. THE RIGHT IION. THE EARL OF LEICESTER, K.G. 'FHE RIGHT IION. THE EARL OF KIMBERLEY LORD WALSINGHAM IIENRY STEVENSON, F.L.S. SIR F. G. M. BOILEAU, Bart. MICHAEL BEVERLEY, M.D. SIR WILLOUGHBY JONES, Bart. HERBERT D. GELDART SIR HENRY STRACEY, Bart. JOHN B. BRIDGMAN, F.L.S. W. A. TYSSEN AMHERST, M.P. T. G. BAYFIELD Treasurer. MR. II. D. GELD ART. li>nn. jSrcrrtaru. MR. W. H. BIDWELL. Committer. MR. T. R. PINDER DR. S. T. TAYLOR MR. F. SUTTON MR. C. CLOWES W. MR. S. CORDER MR. 0. CORDER MR. J. ORFEUR MR. A. W. PRESTON MR. T. SOUTHWELL Journal Committee. PROFESSOR NEWTON MR. M. P. SQUIRRELL MR. JAMES REEVE MR, T. SOUTHWELL MR. B. E. FLETCHER 3itbifor. MR. S. W. UTTING. LIST OF MEMBERS, 1882—83. A Brown Rev. J. L., M.A. Brown William, Ilaynford Hall Amherst W. A. T., M.P., F.Z.S., Y.P., Brownfield J. Didlington Hall Bulwer W. D. E., Quebec House, East Amyot T. E., F.R.C.S., Diss Dereham Asker G. H., Ingworth Burcham R. P. Burlingham D. Catlin, Lynn B Burton S. IL, M.B. Butcher H. F. Babington Rev. Churchill, D.D., Buxton C. Louis, Bolwick Hall Cockfield Rectory Buxton Geoffrey F., Thorpe Bailey Rev. J., M. -

Draft Agenda

17th ASCOBANS Advisory Committee Meeting AC17/Doc.6-08 (S) rev.2 UN Campus, Bonn, Germany, 4-6 October 2010 Dist. 06 October 2010 Agenda Item 6.1 Project Funding through ASCOBANS Progress of Supported Projects Document 6-08 rev.2 Interim Project Report: Review of Trend Analyses in the ASCOBANS Area Action Requested Take note of the report Comment Submitted by Secretariat NOTE: IN THE INTERESTS OF ECONOMY, DELEGATES ARE KINDLY REMINDED TO BRING THEIR OWN COPIES OF DOCUMENTS TO THE MEETING Secretariat’s Note Comments received by the author during the 17th Meeting of the ACOBANS Advisory Committee were incorporated in this revision. REVIEW OF CETACEAN TREND ANALYSES IN THE ASCOBANS AREA Peter G.H. Evans1, 2 1 Sea Watch Foundation, Ewyn y Don, Bull Bay, Amlwch, Isle of Anglesey LL68 9SD, Wales, UK 2 School of Ocean Sciences, University of Bangor, Menai Bridge, Isle of Anglesey LL59 5AB, Wales, UK . 1. Introduction The 16th Meeting of the Advisory Committee recommended that a review of trend analyses of stranding and other data on small cetaceans in the ASCOBANS area be carried out. The ultimate aim is to provide on an annual basis AC members with an accessible, readable and succinct overview of trends in status, distribution and impacts of small cetaceans within the ASCOBANS Agreement Area. This should combine data sets of different stakeholders and countries. 2. Terms of Reference To achieve the above aim of the project, a three-staged process was proposed: Step 1: Identify where data of interest (e.g. stranding data, but also data on -

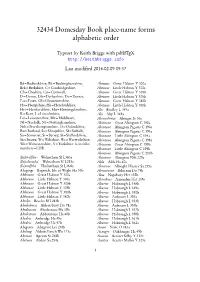

32434 Domesday Book Place-Name Forms Alphabetic Order

32434 Domesday Book place-name forms alphabetic order Typeset by Keith Briggs with pdfLATEX http://keithbriggs.info Last modified 2014-02-09 09:37 Bd=Bedfordshire, Bk=Buckinghamshire, Abetune Great Habton Y 300a Brk=Berkshire, C=Cambridgeshire, Abetune Little Habton Y 300a Ch=Cheshire, Co=Cornwall, Abetune Great Habton Y 305b D=Devon, Db=Derbyshire, Do=Dorset, Abetune Little Habton Y 305b Ess=Essex, Gl=Gloucestershire, Abetune Great Habton Y 380b Ha=Hampshire, He=Herefordshire, Abetune Little Habton Y 380b Hrt=Hertfordshire, Hu=Huntingdonshire, Abi Bradley L 343a K=Kent, L=Lincolnshire, Abi Aby L 349a Lei=Leicestershire, Mx=Middlesex, Abinceborne Abinger Sr 36a Nf=Norfolk, Nt=Nottinghamshire, Abintone Great Abington C 190a Nth=Northamptonshire, O=Oxfordshire, Abintone Abington Pigotts C 190a Ru=Rutland, Sa=Shropshire, Sf=Suffolk, Abintone Abington Pigotts C 193a So=Somerset, Sr=Surrey, St=Staffordshire, Abintone Little Abington C 194a Sx=Sussex, W=Wiltshire, Wa=Warwickshire, Abintone Abington Pigotts C 198a Wo=Worcestershire, Y=Yorkshire. L in folio Abintone Great Abington C 199b numbers=LDB. Abintone Little Abington C 199b Abintone Abington Pigotts C 200b (In)hvelfiha’ Welnetham Sf L363a Abintone Abington Nth 229a (In)telueteha’ Welnetham Sf L291a Abla Abla Ha 40a (In)teolftha’ Thelnetham Sf L366b Abretone Albright Hussey Sa 255a Abaginge Bagwich, Isle of Wight Ha 53b Abristetone Ibberton Do 75b Abbetune Great Habton Y 300a Absa Napsbury Hrt 135b Abbetune Little Habton Y 300a Absesdene Aspenden Hrt 139a Abbetune Great Habton Y 305b Aburne -

Kiel University

LAST UPDATED: JAN. 2017 KIEL UNIVERSITY CHRISTIAN-ALBRECHTS-UNIVERSITÄT ZU KIEL (full legal name of the institution) ERASMUS-Code D KIEL 01 ECHE 28321 PIC 999839529 Websites http://www.uni-kiel.de http://www.international.uni-kiel.de Postal address Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel International Center, Westring 400, 24118 Kiel, Germany INTERNATIONAL CENTER ERASMUS-Institutional Coordinators Antje VOLLAND, M.A. and Dr. Elisabeth GRUNWALD (Mobility and agreements) Tel.: +49(0)431 880-3717 Fax: +49(0)431 880-7307 [email protected] (same contact) ERASMUS-Incomings Susan BRODE Tel.: +49(0)431 880-1843 [email protected] APPLICATION INFORMATION FOR INCOMING STUDENTS Academic Calendar / Lecture Time Winter Semester 2017/18: 16th Oct 2017 – 14th Feb 2018 („Vorlesungszeiten“) Summer Semester 2018: 2nd Apr 2017 – 20th July 2018 Application Deadline for Winter Semester: 15th June ERASMUS-Students (Incomings) Summer Semester: 15th January How to apply http://www.international.uni-kiel.de/en/application- admission/application-admission/erasmus-incoming Language Requirements - B1 German OR English. For Medicine: B2 German Course Schedule (“Vorlesungsverzeichnis”) http://univis.uni-kiel.de/form Special Courses for Incomings http://www.international.uni-kiel.de/en/study-in- kiel?set_language=en International Study Programs http://www.international.uni-kiel.de/en/application- admission/application-admission/english- master?set_language=en LAST UPDATED: JAN. 2017 INFORMATION FOR ACCEPTED STUDENTS Registration (“Einschreibung”) -

Sixth Workshop on Baltic Sea Ice Climate August 25–28, 2008 Lammi Biological Station, Finland

UNIVERSITY OF HELSINKI DEPARTMENT OF PHYSICS REPORT SERIES IN GEOPHYSICS No 61 Proceedings of The Sixth Workshop on Baltic Sea Ice Climate August 25–28, 2008 Lammi Biological Station, Finland HELSINKI 2009 UNIVERSITY OF HELSINKI DEPARTMENT OF PHYSICS REPORT SERIES IN GEOPHYSICS No 61 Cover: Participants of the workshop in front of the main building of Lammi biological station (Eija Riihiranta). Proceedings of The Sixth Workshop on Baltic Sea Ice Climate August 25–28, 2008 Lammi Biological Station, Finland HELSINKI 2009 2 Preface The importance of sea ice in the Baltic Sea has been addressed in the Baltic Sea Ice Workshops. The ice has been identified as a key element in the water and energy cycles and ecological state of the Baltic Sea. The variability in sea ice conditions is high and due to the short thermal memory of the Baltic Sea closely connected to the actual weather conditions. The spatial and temporal long-term variability of the ice cover has been discussed in the Baltic Sea Ice Workshops. One motivation of the workshop series, which started in 1993, was that sea ice is not properly treated in Baltic Sea research in general although the ice season has a major role in the annual cycle of the Baltic Sea. This still holds true, which is a severe bias since in environmental problems, such as oil spill accidents in winter and long term transport of pollutants, the ice conditions play a critically important role. Also in regional climate changes the Baltic Sea ice cover is a sensitive key factor. In the Baltic Sea Ice Climate Workshops these topics have been extensively discussed, in addition to basic Baltic Sea ice science questions. -

Dokument in Microsoft Internet Explorer

20th Baltic Sea Ice Meeting (BSIM-20) paragraph4 International fairway sections and areas for ice report in Baltic Sea Ice Code Valid from Ice Season 2001/2002 DENMARK FAIRWAY SECTIONS AND AREAS FOR ICE REPORT AA 1 Sea area N of Hammeren BB 1 Sea area W of Ven 2 Fairway to Rönne 2 Sea area E of Ven 3 Sea area between Rönne and 3 Sea area off Helsingör Falsterbo 4 Sea area off Falsterbo 4 Sea area off Nakkehoved 5 Fairway through Drogden 5 Sea area S of Hesselö 6 Fairway to Köbenhavn 6 Fairway to Isefjord – Kyndby Verket CC 1 Sea area off Mön lighthouse Route T DD 1 Agersösund – Stignaes 2 Sea area S of Gedser Route T 2 Storebaelt channel, western part 3 Sea area S of Rödby harbour 3 Storebaelt channel, eastern part Route T 4 Sea area SE of Keldsnor Route T 4 Sea area E of Romsö Route T 5 Sea area off Spodsbjerg Route T 5 Fairway to Kalundborg –oilharbour 6 Sea area W of Omö Route T 6 Sea area W of Rösnaes Route T EE 1 Sea area W of Sjaellands rev Route T FF 1 Southern entrance to Lillebaelt, Skjoldnaes 2 Sea area W of Hesselö Route T 2 Sea area off Helnaes 3 Sea area E of Anholt Route T 3 Fairway to Åbenrå –Enstedvaerket 4 Sea area W of Fladen lighthouse Route T 4 Sea area off Assens 5 Sea area NW of Kummelbank Route T 5 Kolding Yderfjord to the bridges 6 Sea area N of Skagen Route T 6 Fairway to Esbjerg GG 1 Fairway at Fredricia to the bridges HH 1 Sea area off Fornaes 2 Sea area N of Aebelö 2 Fairway to Randers 3 Fairway to Odense 3 Entrance at Hals Barre 4 Sea area at Vesborg lighthouse 4 Fairway to Aalborg 5 Sea area S of Sletterhage -

Kett's Rebellion 1548

Jackie Morrallee Revised October 2009 Civil Disturbances Kett’s Rebellion 1549 “It was a time of poverty, uncertainty and shifting fortunes.” These were the comments made by Bruce Robinson1 and seem to accurately sum up the prevailing mood throughout the country during the middle of the sixteenth century. In January 1549 Crammer‟s Book of Common Prayer was introduced and the first full English Church Service was conducted, to further rid the churches of all traces of papal influence, stained glass windows and statues of saints were being smashed, painted walls white-washed and vestments sold. With the increasing resentment felt for the gentry by local agricultural communities due the practice of enclosing common land on which villagers grazed their sheep and cultivated their crops and the upheaval brought about by the Protestant reforms, the country had become a powder keg that was waiting to explode. Though East Anglia seems to have accepted the religious movement towards the Common Prayer Book and all that it entailed, there was anger at the gradual erosion over the years of their right to graze their livestock and grow their crops. In 1520 the villagers of Sculthorpe outside Fakenham, had made representation to the Star Chamber that Sir Henry Fermour had pastured 800 sheep on the whole of the common land when he actually owned only just five acres common land. At Walsingham in 1537, under the cover of an archery competition held at Binham2, a plot was uncovered to organize a protest against what was a local injustice and which later led to the execution of the leaders.