Kett's Rebellion 1548

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

County Town Title Film/Fiche # Item # Norfolk Benefices, List Of

County Town Title Film/Fiche # Item # Norfolk Benefices, List of 1471412 It 44 Norfolk Census 1851 Index 6115160 Norfolk Church Records 1725-1812 1526807 It 1 Norfolk Marriage Allegations Index 1811-1825 375230 Norfolk Marriage Allegations Index 1825-1839 375231 Norfolk Marriage Allegations Index 1839-1859 375232 Norfolk Marriage Bonds 1715-1734 1596461 Norfolk Marriage Bonds 1734-1749 1596462 Norfolk Marriage Bonds 1770-1774 1596563 Norfolk Marriage Bonds 1774-1781 1596564 Norfolk Marriage Bonds 1790-1797 1596566 Norfolk Marriage Bonds 1798-1803 1596567 Norfolk Marriage Bonds 1812-1819 1596597 Norfolk Marriages Parish Registers 1539-1812 496683 It 2 Norfolk Probate Inventories Index 1674-1825 1471414 It 17-20 Norfolk Tax Assessments 1692-1806 1471412 It 30-43 Norfolk Wills V.101 1854-1857 167184 Norfolk Alburgh Parish Register Extracts 1538-1715 894712 It 5 Norfolk Alby Parish Records 1600-1812 1526778 It 15 Norfolk Aldeby Church Records 1725-1812 1526786 It 6 Norfolk Alethorpe Census 1841 438859 Norfolk Arminghall Census 1841 438862 Norfolk Ashby Church Records 1725-1812 1526786 It 7 Norfolk Ashby Parish Register Extracts 1646 894712 It 5 Norfolk Ashwell-Thorpe Census 1841 438851 Norfolk Aslacton Census 1841 438851 Norfolk Baconsthorpe Parish Register Extracts 1676-1770 894712 It 6 Norfolk Bagthorpe Census 1841 438859 Norfolk Bale Census 1841 438862 Norfolk Bale Parish Register Extracts 1538-1716 894712 It 6 Norfolk Barmer Census 1841 438859 Norfolk Barney Census 1841 438859 Norfolk Barton-Bendish Church Records 1725-1812 1526807 It -

Parish Registers and Transcripts in the Norfolk Record Office

Parish Registers and Transcripts in the Norfolk Record Office This list summarises the Norfolk Record Office’s (NRO’s) holdings of parish (Church of England) registers and of transcripts and other copies of them. Parish Registers The NRO holds registers of baptisms, marriages, burials and banns of marriage for most parishes in the Diocese of Norwich (including Suffolk parishes in and near Lowestoft in the deanery of Lothingland) and part of the Diocese of Ely in south-west Norfolk (parishes in the deanery of Fincham and Feltwell). Some Norfolk parish records remain in the churches, especially more recent registers, which may be still in use. In the extreme west of the county, records for parishes in the deanery of Wisbech Lynn Marshland are deposited in the Wisbech and Fenland Museum, whilst Welney parish records are at the Cambridgeshire Record Office. The covering dates of registers in the following list do not conceal any gaps of more than ten years; for the populous urban parishes (such as Great Yarmouth) smaller gaps are indicated. Whenever microfiche or microfilm copies are available they must be used in place of the original registers, some of which are unfit for production. A few parish registers have been digitally photographed and the images are available on computers in the NRO's searchroom. The digital images were produced as a result of partnership projects with other groups and organizations, so we are not able to supply copies of whole registers (either as hard copies or on CD or in any other digital format), although in most cases we have permission to provide printout copies of individual entries. -

Transactions of the Norfolk and Norwich Naturalists' Society

: ; TRANSACTIONS OF THE IlutTnlk anti BntTtfick SOCIETY Presented to the Members for - 1882 83 . A OL. III. —Part iv. Itorbidi PRINTED BY FLETCHER AND SON. 1383 . OFFICERS FOR 1882-83. resilient. MR. H. D. GELDART. fEr^rrstornt. MR. J. II. GURNEY, Jun., F.Z.S. Ficc^Jrrsiticnts. THE RIGHT IION. THE EARL OF LEICESTER, K.G. 'FHE RIGHT IION. THE EARL OF KIMBERLEY LORD WALSINGHAM IIENRY STEVENSON, F.L.S. SIR F. G. M. BOILEAU, Bart. MICHAEL BEVERLEY, M.D. SIR WILLOUGHBY JONES, Bart. HERBERT D. GELDART SIR HENRY STRACEY, Bart. JOHN B. BRIDGMAN, F.L.S. W. A. TYSSEN AMHERST, M.P. T. G. BAYFIELD Treasurer. MR. II. D. GELD ART. li>nn. jSrcrrtaru. MR. W. H. BIDWELL. Committer. MR. T. R. PINDER DR. S. T. TAYLOR MR. F. SUTTON MR. C. CLOWES W. MR. S. CORDER MR. 0. CORDER MR. J. ORFEUR MR. A. W. PRESTON MR. T. SOUTHWELL Journal Committee. PROFESSOR NEWTON MR. M. P. SQUIRRELL MR. JAMES REEVE MR, T. SOUTHWELL MR. B. E. FLETCHER 3itbifor. MR. S. W. UTTING. LIST OF MEMBERS, 1882—83. A Brown Rev. J. L., M.A. Brown William, Ilaynford Hall Amherst W. A. T., M.P., F.Z.S., Y.P., Brownfield J. Didlington Hall Bulwer W. D. E., Quebec House, East Amyot T. E., F.R.C.S., Diss Dereham Asker G. H., Ingworth Burcham R. P. Burlingham D. Catlin, Lynn B Burton S. IL, M.B. Butcher H. F. Babington Rev. Churchill, D.D., Buxton C. Louis, Bolwick Hall Cockfield Rectory Buxton Geoffrey F., Thorpe Bailey Rev. J., M. -

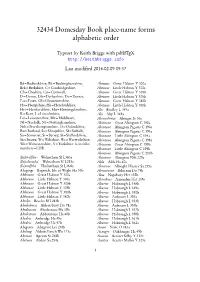

32434 Domesday Book Place-Name Forms Alphabetic Order

32434 Domesday Book place-name forms alphabetic order Typeset by Keith Briggs with pdfLATEX http://keithbriggs.info Last modified 2014-02-09 09:37 Bd=Bedfordshire, Bk=Buckinghamshire, Abetune Great Habton Y 300a Brk=Berkshire, C=Cambridgeshire, Abetune Little Habton Y 300a Ch=Cheshire, Co=Cornwall, Abetune Great Habton Y 305b D=Devon, Db=Derbyshire, Do=Dorset, Abetune Little Habton Y 305b Ess=Essex, Gl=Gloucestershire, Abetune Great Habton Y 380b Ha=Hampshire, He=Herefordshire, Abetune Little Habton Y 380b Hrt=Hertfordshire, Hu=Huntingdonshire, Abi Bradley L 343a K=Kent, L=Lincolnshire, Abi Aby L 349a Lei=Leicestershire, Mx=Middlesex, Abinceborne Abinger Sr 36a Nf=Norfolk, Nt=Nottinghamshire, Abintone Great Abington C 190a Nth=Northamptonshire, O=Oxfordshire, Abintone Abington Pigotts C 190a Ru=Rutland, Sa=Shropshire, Sf=Suffolk, Abintone Abington Pigotts C 193a So=Somerset, Sr=Surrey, St=Staffordshire, Abintone Little Abington C 194a Sx=Sussex, W=Wiltshire, Wa=Warwickshire, Abintone Abington Pigotts C 198a Wo=Worcestershire, Y=Yorkshire. L in folio Abintone Great Abington C 199b numbers=LDB. Abintone Little Abington C 199b Abintone Abington Pigotts C 200b (In)hvelfiha’ Welnetham Sf L363a Abintone Abington Nth 229a (In)telueteha’ Welnetham Sf L291a Abla Abla Ha 40a (In)teolftha’ Thelnetham Sf L366b Abretone Albright Hussey Sa 255a Abaginge Bagwich, Isle of Wight Ha 53b Abristetone Ibberton Do 75b Abbetune Great Habton Y 300a Absa Napsbury Hrt 135b Abbetune Little Habton Y 300a Absesdene Aspenden Hrt 139a Abbetune Great Habton Y 305b Aburne -

Transactions of the Norfolk and Norwich Naturalists' Society

; TRANSACTIONS OK THK NORFOLK AND NORWICH VOL. III. 187D — 80 to 1883—84. |torfoieb PRINTED BY FLETCHER AND SON. 1884. CONTENTS ALPHABETICAL LIST OF CONTRIBUTORS. Barnard A. M., 424, 567 Barrett C. G., 683 Bennett Aetiiue, 379, 568, 633 Bidwell Edward, 526 Bi dwell AV. H., 212 Bridgman J. B., 367 Christy R. M., 588 Coeder 0., 155 DuPoet J. M., 194, 200 Edwards James, 266, 700 Feilden H. AV., 201 Geldabt H. D., 38, 268, 354, 425, 532, 719 Gurney J. H., 422 Gurney J. H., Jun., 170, 270, 424, 511, 517, 565 566, 581, 597 Habmer F. AV., 71 Harmer S. F., 604 IIarting J. E., 79 II arvi e-Brown J. A., 47 IIeddle M. F., 61 Kitton F., 754 Linton E. F., 561 Lowe John, 677 Newton Alfred, 34 Newton E. T., 654 Norgate Frank, 68, 351, 383 Power F. D., 345 r Preston A. AA ., 505, 646 Plowright C. B., 152, 266, 730 Quinton John, Jun., 140 Reid Clement, 503, 601, 631, 789 Southwell T., 1, 95, 149, 178, 228, 369, 415, 419, 474, 475, 482, 539 564, 610, 644, 657 Stevenson II., 99, 120, 125, 326, 373, 392, 467, 542, 771 Utcher H. M., 569 AA'alsingham Lord, 313 AVheeler F. D., 28, 262 AVoodward H. B., 36, 279, 318, 439, 525, 637, 789 Young J., 519 // ALPHABETICAL LIST OF SUBJECTS. Amber in Norfolk, 601 Fauna and Flora of Norfolk— Ampelis garrulus, 326 Part IX. Hymenoptera, 367 American Bison, 17 „ X. Marine Algae, 532 Atlantic Right- whale, 228 „ I. Mammalia, 657 „ IX. Fishes, 677 Balsena biscayensis, 228 „ V. -

April Beacon 2018

Contact Who’s Who St Peter & St Paul Fakenham Parish Church Christ Church, Fulmodeston Rector Marriage Preparation Croxton Road, Fulmodeston, Revd Francis Mason 01328 862268 Amanda Sands 01328 878218 or NR21 0LZ [email protected] 07789 225011 Priest in charge The Rectory Office 01328 862268 Stepping Stones Revd Francis Mason 01328 862268 Gladstone Road, Fakenham, Elaine Burbidge 01328 851848 [email protected] NR21 9BZ [email protected] Messy Church Churchwarden For parish information, baptisms and Ann Rae Sims 01328 864537 Andrew Lee 01328 878870 wedding bookings also see our website. Mothers’ Union Please feel free to contact us about Church postcode (for satnav) - Felicity Randall 01328 862443 services and events or the Rectory NR21 9BX Office where enquiries about Church Women’s Guild baptisms, weddings and funerals can The Church is open from 8.45am - Joy Gill 01328 863632 be made. 4.00pm every day Church Flowers Readers Judith Smyth 01328 864061 Elaine Burbidge 01328 851848 Amanda Sands 01328 878218 Bell Ringers Welcome to a new Kevin Allcock 01328 853928 advertiser this month: Churchwardens Support in Loss Group Roger Burbidge 01328 851848 Judith Smyth 01328 864061 p 12 Gillian Lee, piano lessons Keith Osborn 07887 877650 [email protected] Christmas Tree Festival Fabric Officer Anne Peppitt 07999 532002 Judith Inward 01328 855269 Beacon Editor and advertising Church Treasurer Linda Frost 01328 862919 Via Rectory Office 01328 862268 [email protected] Sacristan Beacon Treasurer John Dunn 01328 856644 Patrick Sheppard 01328 855013 Find us online: Child Protection Officer Beacon Distribution Paul Nielsen 07798 766357 Elaine Burbidge 01328 851848 Web [email protected] www.fakenhamparishchurch.org.uk Vulnerable Adults Officer 01328 862268 Website Administrator Fakenham Parish Church via Rectory office Keith Osborn 07887 877650 [email protected] @fakenhampchurch Organist/Choirmaster Jonathan Dodd 01328 862268 via Rectory office The copy date for the May 2018 Beacon is 5th April. -

The Sheep,Corn Husbandry of Norfolk in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries by K

The Sheep,Corn Husbandry of Norfolk in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries By K. J. ALLISON I URING the later seventeenth century and throughout the eighteenth, new methods of husbandry were gradually established in Norfolk. The new 'Norfolk Husbandry', developed above all in the north- west of the county, involved crops, rotations, methods of stock feeding, and conditions of land tenure which greatly improved upon earlier practices. In the eighteenth century, Townshend, Coke, L'Estrange, and Walpole were prominent in the systematic development of the new husbandry, but it should be remembered that the various individual practices were being gradually introduced by a multitude of small farmers long before the big estate owners achieved their fame. The object of this paper is to describe the older system which was to be transformed into the new 'Norfolk Husbandry' by the enclosure of open arable fields and commons. If the Broads and Fens are excluded, an open-field, sheep-corn husbandry can be discerned over about two-thirds of the county in the later Middle Ages and the sixteenth century. The other third, distinguished on Fig. I, may appropriately be called the Wood-Pasture Region with its heavier and inherently more fertile soils. The contrast was well appreciated in the past: one seventeenth-century writer noted that the county "is compownded and sorted of soyles apte for grayne and sheepe, and of soyles apt for woode and pasture. ''1 In the area of grain and sheep, with which this paper is princi- pally concerned, the soils were light or medium in character and their sandi- ness made them relatively (and sometimes absolutely) infertile. -

Feb Beacon 19

February 2019 Photo by Luke Michael on Unsplash Audrey meets performer Rachael Bird, Active Fakenham are seeking volunteers for their work this year, Kay is out and about on travels with her granddaughter, and we have the final charity results for the Christmas Tree Festival. Contact Who’s Who St Peter & St Paul Fakenham Parish Church Christ Church, Fulmodeston Rector Marriage Preparation Rev’d Francis Mason 01328 862268 Amanda Sands 01328 878218 or Croxton Road, Fulmodeston, [email protected] 07789 225011 NR21 0LZ The Rectory Office 01328 862268 Stepping Stones Priest in charge Rev’d Francis Mason 01328 862268 Gladstone Road, Fakenham, Elaine Burbidge 01328 851848 NR21 9BZ [email protected] [email protected] Messy Church Churchwarden Ann Rae Sims 01328 864537 For parish information, baptisms and Andrew Lee 01328 878870 wedding bookings also see our Mothers’ Union Please feel free to contact us about website. Felicity Randall 01328 862443 Church postcode (for satnav) - services and events or the Rectory Office where enquiries about NR21 9BX Church Women’s Guild baptisms, weddings and funerals can The Church is open from 8.45am - Joy Gill 01328 863632 2.00pm every day. be made. Church Flowers Readers Judith Smyth 01328 864061 Elaine Burbidge 01328 851848 Linda Frost 01328 862919 Bell Ringers Amanda Sands 01328 878218 Kevin Allcock 01328 853928 John 14.17 Churchwardens Support in Loss Group Roger Burbidge 01328 851848 Judith Smyth 01328 864061 This is the Spirit of truth, whom the Keith Osborn 07887 877650 world cannot receive, because it [email protected] Christmas Tree Festival neither sees him nor knows him. -

Toponyms As Evidence of Linguistic Influence on the British Isles

Toponyms as Evidence of Linguistic Influence on the British Isles Tintor, Sven Master's thesis / Diplomski rad 2011 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: Josip Juraj Strossmayer University of Osijek, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences / Sveučilište Josipa Jurja Strossmayera u Osijeku, Filozofski fakultet Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:142:862958 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-10-02 Repository / Repozitorij: FFOS-repository - Repository of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Osijek Sveučilište J.J. Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet Diplomski studij engleskog i njemačkog jezika i književnosti Sven Tintor Toponyms as Evidence of Linguistic Influence on the British Isles Diplomski rad Doc. dr. sc. Tanja Gradečak Erdeljić Osijek, 2011 Abstract This diploma paper deals with toponyms, also referred to as place names, which can be found on the British Isles as evidence of different linguistic influences that shaped the English language. The aim of this paper is to give a brief overview of naming patterns and affixes that were used in the processes of naming. The toponyms are presented in five groups that are arranged in a chronological order as the settlements on the Isles occurred. Before the groups are discussed, a short overview of a theoretical part concerning toponymy is provided. The first group consists of Celtic settlers, followed by the Roman invasion, the conceiving of the Old English by the Anglo- Saxons, Viking raids and conquering, and the last group being the Normans. A short overview of the peoples’ settlement or colonization is given for every group, as well as place names and their influence on the English language. -

Official U.S. Bulletin

,,, ; : : : ; • STATES by COMMITTEE on PUBLIC INFORMATION ^ ^ order^ off THE-rWE PRESIDENTPSESIDENT of THE UNITED PUBLISHED DAILY under COMVLEtE Recordaecora of U. S. GOVERNMENT Actioities GEORGE CREEL, Chairman / No. 54T WEDNESDAY, FEBRUAEY 26, 1919. VoL. 3 WASHINGTON, DIVISIONS CONFERENCE OF GOVERNORS ORDER IN WHICH U.S. SCHEDULE OF COMMODITIES REGULAR AND MAYORS AT WHITE HOUSE OVERSEAS NOT IN THE FROM WHICH FRANCE HAS ARMY ARE LISTED FOR RETURN S^ecretary of Labor Calls Meeting 3d and REMOVED IMPORT EMBARGO to Be Held the GEN. PERSHING CABLES SCHEDULE 4tli of March. FROM THE JMED STATES Will Depart From France in the Secretary of Labor Witliaiu B. Wilson to There, Ex- last night telegraphed invitations Order of Their Arrival 100 ANNOUNCEMENT MADE State governors and mayors of some the White cept Where Circumstances May board cities to attend a conference at war trade 4. by House on March 3 and Require Other Arrangements. President will address the con- of The Full Description Given ference. Department authorizes pub- take uj) vital ques- The War The conference will cabled commu- Listed It is lication of the following Articles Heretofore tions affecting business and labor. nication from the commander in chief, the President to establish the desire of * Numbers — Live Ani- definite A E F by before he returns to Europe a “ 1. The following order has been pub- Products Nation-wide policy to stimulate public mals, Animal lished under date of February 21 and and private construction and industi’y will be carried out as far as practicable By-Products Includ- general. in , , in the and ‘ No. -

A Glossary of South Australian Place Names - from Aaron Creek to Zion Hill

A Glossary of South Australian Place Names - From Aaron Creek to Zion Hill A We are said to be making history, but are we not lacking in courtesy in effacing the history of a less fortunate people whom we have displaced… It surely is not necessary to close the annals of this inoffensive simple race, certainly it is not generous of us to destroy their only records, nor is it wise to exclude from mental view the panorama of their past. (Charles Hope Harrris (1846-1915), (Colonial Surveyor} Aaron Creek - It runs through section 34, Hundred of Waitpinga, and recalls Aaron Bennett, who arrived in the Indian in 1849, aged forty, owned section 111 in the same Hundred which he sold to James Collins for £28/10/0 in January 1857. In December 1920, Mr W. Bennett of Delamere, the second son of Aaron Bennett, celebrated his diamond wedding. He came to South Australia with his parents… following which his father was employed as a wheelwright by Mr J.G. Coulls in Blyth Street. Within a few years he had accumulated sufficient funds to purchase land in southern Fleurieu Peninsula and it was there he engaged in mixed farming. The family travelled from Adelaide in a bullock dray over rough tracks and the journey occupied a fortnight. There were no improvements on the place of any kind - neither house, fencing nor cleared land. The first work was to build a house, of slabs, with thatch roof and earth floor, calico windows and containing three rooms in which the family lived for a number of years. -

PITS and PONDS in NORFOLK Hugh C

10 Erdkunde Band XVI Nansen war eine komplizierte Natur mit sehr damit %u tun, nach vorwarts %u schauen." Diesem er er widersprechenden Eigenschaften. Aber be Prinzip folgte als Forschungsreisender und herrschte sie alle mit seinem unbeugsamen dieses brachte ihm seinen friihen Ruhm. Spater Willen, um die Ziele zu erreichen, die sein trat mehr und mehr die Pflicht in den Vorder ebenso groBer Ehrgeiz ihm gesteckt hatte. grund, das bestmogliche im Leben fiir sich selbst zu tun. ?Ich habe meine Schiffe verbrannt und die Briicken und damit fiir die anderen Diese Haltung hinter mir abgebrochen. So verschwendetman keine beherrschte sein von alien bewundertes Rettungs Zeit mit Ruckwartsblicken, denn man hat genug werk. PITS AND PONDS IN NORFOLK Hugh C. Prince With 7 Tables and 21 Figures for their valuable assistance in Zusammenfassung: Gruben und Teicbe in der Graf schaf t Department of Geography Norfolk the field work carried out in the summer 1958 and spring 1959. I am indebted to the many landowners who kindly Von den in der neuesten Ausgabe der Ordnance Survey to the allowed us to inspect their fields, and in particular, Karten 27 015 sind die gro eingetragenen Eintiefungen Earl of Leicester, his Librarian, Dr. W. O. Hassall, and fien Steinbriiehe mit unregelmafiigem Umrifi die auffallig me his Estate Agent, Mr. F. S. Turner, for permitting sten. Sie kommen in in der gan unregelmafiiger Verteilung to consult the map collection and other records at Holk zen Graf schaf t vor, machen zusammen jedoch nur 1,5% ham. To Mr. J. Bryant I owe thanks for drawing the der Gesamtzahl aus.