Assessment Report on Pistacia Lentiscus L., Resin (Mastix) Draft

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SPECIFICATION GUIDE 2020 at Ply Gem Residential Solutions, We Make the Products That Make Beautiful Homes

SPECIFICATION GUIDE 2020 At Ply Gem Residential Solutions, we make the products that make beautiful homes. PLY GEM RESIDENTIAL SOLUTIONS' PRODUCTS LEAD THE INDUSTRY #1 Vinyl Siding in North America #1 Aluminum Accessories in the U.S. #1 Vinyl & Aluminum Windows in the U.S. #2 Overall Windows in the U.S. #3 Fence & Railing in North America Table of Contents Cedar Dimensions™ Siding . 4 – 8 Vinyl Siding Collection . 9 – 13 Dimensions® . 9 Progressions® . 10 Transformations® . 12 Colonial Beaded . 13 Board & Batten . 13 Vinyl Soffit . 14 – 20 Hidden Vent . 14 Beaded . 15 Premium . 16 Standard . 18 Economy . 19 Vinyl Siding & Soffit Accessories . 21 – 30 Designer Accents . 31 – 60 Mounting Blocks . 31 Surface Mounts . 36 Vents . 38 2-Piece Gable Vents . 41 Board & Batten Shutters . 45 12" Standard Shutters . 49 15" Standard Shutters . 51 Standard Shutter Accessories . 54 Custom Shutters . 55 Window Mantels . 56 Door Surround Systems . 59 Designer Accents Color Matrix . 61 – 81 Aluminum Products . 82 – 108 Trim Coil . 82 Soffit . 97 Fascia . 103 Accessories . 106 Gutter Protection Systems . 109 – 115 Leaf Relief ® . 109 Leaf Logic® & Accessories . 115 Roofing Accessories . 116 – 124 Steel Siding . 125 – 132 Specifications & Conformance . 133 – 135 3 Cedar Dimensions TM D7" Shingle Siding Product Code: CEDAR7 Description Package Nominal .090" Thick 10 Pcs ./Ctn . Length: Double 7" 1/2 Sqs ./Ctn . 40 Lbs ./Ctn . Color Availability WHITE White (04) LIGHT Beige (NB), Pewter (NP), Sand (M4), Sunrise Yellow (IQ), Wicker (A7) CLASSIC French Silk (210), -

Kokkalo Menu

salads Quinoa* with black-eyed beans (V++) (*superfood) €6,90 Chopped leek, carrot, red sweet pepper, spring onion, orange fillet, and citrus sauce "Gaia" (Earth) (V+) €7,90 Green and red verdure, iceberg, rocket, beetroots, blue cheese, casious, orange fillet and orange dressing "Summer Pandesia" (V+) €9,90 Green and red verdure, iceberg, rocket, peach fillet, gruyere cheese, dry figs, nuts, molasses, and honey balsamic dressing Santorinian Greek salad (V+) €8,90 Cherry tomatoes, feta cheese, barley bread bites, onion, cucumber, caper and extra virgin olive oil Cretan "Dakos" (V+) €7,50 Rusk with chopped tomato, olive pate, caper Cretan "xinomitzythra" soft cheese and extra virgin olive oil starters from the land Smoked eggplant dip (V++) €4,90 Pine nut seeds, pomegranate, and extra virgin olive oil Tzatziki dip (V+) €3,50 Greek yogurt with carrot, cucumber, garlic and extra virgin olive oil Soft feta cheese balls (V+) €5,50 Served on sundried tomato mayonaise Freshly cut country style potato fries (V++) €3,90 Sereved on a traditional bailer Bruschetta of Cypriot pitta bread with mozzarella and tomato (V+)€4,90 Topped with tomato spoon sweet and fresh basil Santorini's tomato fritters (V++) €4,50 Served with tzatziki dip (V+) Fried spring rolls stuffed with Santorinian sausage and cheese €4,70 Served with a dip of our home-made spicy pepper sauce Fried zucchini sticks (V++) €5,90 Served with tzatziki dip (V+) Variety of muschrooms with garlic in butter lemon sauce (V+) €4,90 Feta cheese in pie crust, topped with cherry-honey (V+) €6,90 -

A Broad Spectrum Activity of Abhal (Juniperus Communis) with Special Reference to Unani System of Medicine

© 2021 JETIR March 2021, Volume 8, Issue 3 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) A Broad Spectrum Activity of Abhal (Juniperus communis) with Special Reference to Unani System of Medicine. A Review * Dr. Aafiya Nargis 1, Dr. Ansari Bilquees Mohammad Yunus 2, Dr. Sharique Zohaib 3, Dr. Qutbuddin Shaikh 4, Dr. Naeem Ahmed Shaikh 5 *1 Associate Professor (HOD) Dept. of Niswan wa Qabalat, Mohammadia Tibbia College, Mansoora, Malegaon 2 Associate professor, Dept. Tashreeh ul Badan, Mohammadia Tibbia College, Mansoora, Malegaon. 3 Associate Professor (HOD) Dept. of Saidla, Mohammadia Tibbia College, Manssoora, Malegaon 4 Professor (HOD), Dept. of Tahaffuzi wa Samaji Tibb, Markaz Unani Medical College and Hospital. Kozhikode. 5 Professor (HOD), Dept. of Ain, Uzn, Anf, Halaq wa Asnan, Markaz Unani Medical College and Hospital. Kozhikode. Abstract:- Juniperus communis is a shrub or small evergreen tree, native to Europe, South Asia, and North America, and belongs to family Cupressaceae. It has been widely used as herbal medicine from ancient time. Traditionally the plant is being potentially used as antidiarrhoeal, anti-inflammatory, astringent, and antiseptic and in the treatment of various abdominal disorders. The main chemical constituents, which were reported in J. communis L. are 훼-pinene, 훽-pinene, apigenin, sabinene, 훽-sitosterol, campesterol, limonene, cupressuflavone, and many others Juniperus communis L. (Abhal) is an evergreen aromatic shrub with high therapeutic potential in human diseases. This plant is loaded with nutrition and is rich in aromatic oils and their concentration differ in different parts of the plant (berries, leaves, aerial parts, and root). The fruit berries contain essential oil, invert sugars, resin, catechin , organic acid, terpenic acids, leucoanthocyanidin besides bitter compound (Juniperine), flavonoids, tannins, gums, lignins, wax, etc. -

Review Article Five Pistacia Species (P. Vera, P. Atlantica, P. Terebinthus, P

Hindawi Publishing Corporation The Scientific World Journal Volume 2013, Article ID 219815, 33 pages http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2013/219815 Review Article Five Pistacia species (P. vera, P. atlantica, P. terebinthus, P. khinjuk,andP. lentiscus): A Review of Their Traditional Uses, Phytochemistry, and Pharmacology Mahbubeh Bozorgi,1 Zahra Memariani,1 Masumeh Mobli,1 Mohammad Hossein Salehi Surmaghi,1,2 Mohammad Reza Shams-Ardekani,1,2 and Roja Rahimi1 1 Department of Traditional Pharmacy, Faculty of Traditional Medicine, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran 1417653761, Iran 2 Department of Pharmacognosy, Faculty of Pharmacy, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran 1417614411, Iran Correspondence should be addressed to Roja Rahimi; [email protected] Received 1 August 2013; Accepted 21 August 2013 Academic Editors: U. Feller and T. Hatano Copyright © 2013 Mahbubeh Bozorgi et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Pistacia, a genus of flowering plants from the family Anacardiaceae, contains about twenty species, among them five are more popular including P. vera, P. atlantica, P. terebinthus, P. khinjuk, and P. l e nti s c u s . Different parts of these species have been used in traditional medicine for various purposes like tonic, aphrodisiac, antiseptic, antihypertensive and management of dental, gastrointestinal, liver, urinary tract, and respiratory tract disorders. Scientific findings also revealed the wide pharmacological activities from various parts of these species, such as antioxidant, antimicrobial, antiviral, anticholinesterase, anti-inflammatory, antinociceptive, antidiabetic, antitumor, antihyperlipidemic, antiatherosclerotic, and hepatoprotective activities and also their beneficial effects in gastrointestinal disorders. -

Aegean Secrets Welcome

. Aegean Secrets The recipes you are about to try have been passed on to modern Aegean Island Cuisine by countless generations, with secrets and recipes exchanged from mother to daughter since the Neolithic era. Please take the time to use all of your senses while enjoying the unique, ancient flavors and aromas of the Aegean Islands that we are sharing with you today. Καλή Όρεξη, Chef Argiro Barbarigou. Welcome ~ SALATOURI ~ Fish salad with a lemon and herb sauce Upon returning from a long fishing trip, fishermen would rest in a traditional «Καφενίων» (Traditional Mezze establishment) and would regale their comrades over a plate of «Σαλατούρι». ~ FAVA (VEGAN) ~ Fava bean puree served with caramelized onions, capers, olives and e.v.olive oil One of the oldest dishes served in the Aegean, Fava beans have been uncovered in Santorini excavations dating as far back as 3000 B.C. Greek families consider it a staple food and serve it at least once a week. ~ HTYPITI (LACTO VEGETARIAN) ~ Spicy Feta cheese spread with sun-dried peppers served on pita bread with e.v.o oil. Feta cheese, has been manufactured in Greece since before the ancient Greeks with its creation attributed in the Odyssey to Polyphemus the famous cyclops that Odysseus tricks! This same meal without the peppers can be made with a variety of herbs. Wine Pairing: Kir Yianni Sparkling Rose 2016 Aegean Heritage Flavors ~ NTOMATOSALATA & FOUSKOTI (LACTO VEGETARIAN) ~ Tomato salad with black eyed beans, caper leaves, «Κρίταμο» (samphire), Cycladic fresh cheese, E.V. olive oil and oregano. Served with FOUSKOTI a traditional island bread with mastic, saffron, anise and flax seeds. -

The Correct Gender of Schinus (Anacardiaceae)

Phytotaxa 222 (1): 075–077 ISSN 1179-3155 (print edition) www.mapress.com/phytotaxa/ PHYTOTAXA Copyright © 2015 Magnolia Press Correspondence ISSN 1179-3163 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.222.1.9 The correct gender of Schinus (Anacardiaceae) SCOTT ZONA Dept. of Biological Sciences, OE 167, Florida International University, 11200 SW 8 St., Miami, Florida 33199 USA; [email protected] Species of the genus Schinus Linnaeus (1753) (Anacardiaceae) are native to the Americas but are found in many tropical and subtropical parts of the world, where they are cultivated as ornamentals or crops (“pink peppercorns”) or they are invasive weeds. Schinus molle L. (1753: 388) is a cultivated ornamental tree in Australia, California, Mexico, the Canary Islands, the Mediterranean, and elsewhere (US Forest Service 2015). In Hawaii, Florida, South Africa, Mascarene Islands, and Australia, Schinus terebinthifolia Raddi (1820: 399) is an aggressively invasive pest plant, costing governments millions of dollars in damages and control (Ferriter 1997). Despite being an important and widely known genus, the gender of the genus name is a source of tremendous nomenclatural confusion, if one judges from the orthographic variants of the species epithets. Of the 38 accepted species and infraspecific taxa on The Plant List (theplantlist.org, ver. 1.1), one is a duplicated name, 18 are masculine epithets (but ten of these are substantive epithets honoring men and are thus properly masculine [Nicolson 1974]), 12 are feminine epithets (one of which, arenicola, is always feminine [Stearn 1983]), and seven have epithets that are the same in any gender (or have no gender, as in the case of S. -

Mastic Beach-Shirley Risk Assessment Report

SuffolkSuffolk CountyCounty VectorVector Control & Wetlands Management Long TermTerm PlanPlan && Environmental Impact Statement Task 8: Impact Assessment Task Report Appendix to the Quantitative Risk Assessment: Mastic BeachBeach-Shirley Risk Assessment Report Prepared for: Suffolk County Department of Public Works Suffolk County Department of Health Services Suffolk County, New York Prepared by: CASHIN ASSOCIATES, P.C. 1200 Veterans Memorial Highway, Hauppauge, NY November 20052005 Suffolk County Vector Control and Wetlands Management Long-Term Plan Mastic Beach – Shirley Risk Assessment Task Eight – Impact Assessment August 2005 SUFFOLK COUNTY VECTOR CONTROL AND WETLANDS MANAGEMENT LONG - TERM PLAN AND ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT PROJECT SPONSOR Steve Levy Suffolk County Executive Department of Public Works Department of Health Services Charles J. Bartha, P.E. Brian L. Harper, M.D., M.P.H. Commissioner Commissioner Richard LaValle, P.E. Vito Minei, P.E. Chief Deputy Commissioner Director, Division of Environmental Quality Leslie A. Mitchel Deputy Commissioner PROJECT MANAGEMENT Project Manager: Walter Dawydiak, P.E., J.D. Chief Engineer, Division of Environmental Quality, Suffolk County Department of Health Services Suffolk County Department of Suffolk County Department of Public Works, Division of Health Services, Office of Ecology Vector Control Martin Trent Dominick V. Ninivaggi Acting Chief Superinte ndent Kim Shaw Tom Iwanejko Bureau Supervisor Principal Environmental Robert M. Waters Entomologist Bureau Supervisor Mary E. Dempsey Laura Bavaro Biologist Environmental Analyst Phil DeBlasi Environmental Analyst Jeanine Schlosser Principal Clerk Cashin Associates, PC i Suffolk County Vector Control and Wetlands Management Long-Term Plan Mastic Beach – Shirley Risk Assessment Task Eight – Impact Assessment August 2005 SUFFOLK COUNTY LONG TERM PLAN CONSULTANT TEAM Cashin Associates, P.C. -

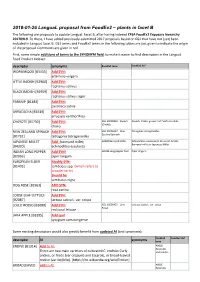

2018-01-26 Langual Proposal from Foodex2 – Plants in Facet B

2018-01-26 LanguaL proposal from FoodEx2 – plants in facet B The following are proposals to update LanguaL Facet B, after having indexed EFSA FoodEx2 Exposure hierarchy 20170919. To these, I have added previously-submitted 2017 proposals based on GS1 that have not (yet) been included in LanguaL facet B. GS1 terms and FoodEx2 terms in the following tables are just given to indicate the origin of the proposal. Comments are given in red. First, some simple additions of terms to the SYNONYM field, to make it easier to find descriptors in the LanguaL Food Product Indexer: descriptor synonyms FoodEx2 term FoodEx2 def WORMWOOD [B3433] Add SYN: artemisia vulgaris LITTLE RADISH [B2960] Add SYN: raphanus sativus BLACK RADISH [B2959] Add SYN: raphanus sativus niger PARSNIP [B1483] Add SYN: pastinaca sativa ARRACACHA [B3439] Add SYN: arracacia xanthorrhiza CHAYOTE [B1730] Add SYN: GS1 10006356 - Squash Squash, Choko, grown from Sechium edule (Choko) choko NEW ZEALAND SPINACH Add SYN: GS1 10006427 - New- Tetragonia tetragonoides Zealand Spinach [B1732] tetragonia tetragonoides JAPANESE MILLET Add : barnyard millet; A000Z Barnyard millet Echinochloa esculenta (A. Braun) H. Scholz, Barnyard millet or Japanese Millet. [B4320] echinochloa esculenta INDIAN LONG PEPPER Add SYN! A019B Long pepper fruit Piper longum [B2956] piper longum EUROPEAN ELDER Modify SYN: [B1403] sambucus spp. (which refers to broader term) Should be sambucus nigra DOG ROSE [B2961] ADD SYN: rosa canina LOOSE LEAF LETTUCE Add SYN: [B2087] lactusa sativa L. var. crispa LOLLO ROSSO [B2088] Add SYN: GS1 10006425 - Lollo Lactuca sativa L. var. crispa Rosso red coral lettuce JAVA APPLE [B3395] Add syn! syzygium samarangense Some existing descriptors would also greatly benefit from updated AI (and synonyms): FoodEx2 FoodEx2 def descriptor AI synonyms term ENDIVE [B1314] Add to AI: A00LD Escaroles There are two main varieties of cultivated C. -

OLD-SCHOOL OPERATION from Humble Origins, the Peña Family Built a Nearly 60-Year-Old Business Based on Basics Page 14

Exclusively serving plumbing contractors and franchisees | plumbermag.com March 2021 OLD-SCHOOL OPERATION From humble origins, the Peña family built a nearly 60-year-old business based on basics Page 14 On The Road REFERRAL PROGRAMS CAN HELP CUSTOMERS, AND YOUR COMPANY Page 24 In The Shop TIME TO GO GREEN WITH NEW COMPANY VEHICLES Page 28 THE ULTIMATE PIPE COATING PACKAGE QUIK-COATING SYSTEM FOR DRAIN, WASTE AND VENT PIPES RESTORE YOUR PIPES TO LIKE NEW CONDITION PERFECT FOR 2”-16” PIPES EVERY SYSTEM INCLUDES HANDS-ON TRAINING! 100’ INSPECTION CAMERA This affordable inspection camera is portable, flexible and GREAT on smaller diameter pipes. RENSSI HIGH-SPEED DRAIN CLEANING MACHINE 3-CHAIN CHAIN KNOCKER The perfect match for our Quik-Coating System, TOP CHOICE FOR PLUMBERS/DRAIN CLEANERS excellent for cleaning & prepping pipes. Pls_Quik-Coating.indd 1 1/26/21 10:08 AM THE ULTIMATE PIPE COATING PACKAGE QUIK-COATING SYSTEM FOR DRAIN, WASTE AND VENT PIPES RESTORE YOUR PIPES TO LIKE NEW CONDITION PERFECT FOR 2”-16” PIPES EVERY SYSTEM INCLUDES HANDS-ON TRAINING! 100’ INSPECTION CAMERA This affordable inspection camera is portable, flexible and GREAT on smaller diameter pipes. RENSSI HIGH-SPEED DRAIN CLEANING MACHINE 3-CHAIN CHAIN KNOCKER The perfect match for our Quik-Coating System, TOP CHOICE FOR PLUMBERS/DRAIN CLEANERS excellent for cleaning & prepping pipes. Pls_Quik-Coating.indd 1 1/26/21 10:08 AM CONTENTS March 2021 From the Editor: 8 Looking for Improvement Take time to work with your team one-on-one to build a love and dedication to the industry and your company. -

Of Martes Martes, Genetta Genetta and Felis Catus

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by I-Revues SEASONALITY AND RELATIONSHIPS OF FOOD RESOURCE USE OF MARTES MARTES, GENETTA GENETTA AND FELIS CA TUS IN THE BALEARIC ISLANDS Anthony P. CLEVENGER* Diet studies increase our understanding of the foods available to a predator, the predatory capabilities of the species, and the limitations their environment places on their food choices. On small islands, information on the diet character istics of carnivores is essential for assessing their role in regulating their prey populations and potential impacts on endemie prey species (Karl & Best, 1982 ; King, 1984 ; Fitzgerald & Veitch, 1985). In the western Mediterranean Basin, carnivores occur on every major island, however, they have been the focus of relatively few studies. Severa! species have received attention due to their body size differences when compared to nearby mainland forms, but besides the taxonomie studies that have been carried out (Frechkop, 1963 ; Delibes, 1977 ; Hutterer & Geraets, 1978 ; Alcover et al., 1986 ; Delibes & Amores, 1986), practically nothing is known about the species basic ecolo gy. Published diet studies from insular Mediterranean carnivore populations have been hampered by small sample sizes or restricted sampling periods. In this study year-round food habits data were collected from three carnivore species in the Balearic Islands. Seasonal diets are characterized, their variability measured, and diet diversity values calculated in order to describe the trophic relationships : 1) between pi ne martens (Martes martes) and spotted genets (Genetta genetta) on Mallorca ; 2) between spotted genets and ferai cats (Felis catus) on Cabrera, and 3) among genets on Mallorca, Ibiza, and Cabrera. -

Assessment Report on Pistacia Lentiscus L., Resina (Mastic) Final

2 February 2016 EMA/HMPC/46756/2015 Committee on Herbal Medicinal Products (HMPC) Assessment report on Pistacia lentiscus L., resina (mastic) Final Based on Article 16d(1), Article 16f and Article 16h of Directive 2001/83/EC (traditional use) Herbal substance(s) (binomial scientific name of Pistacia lentiscus L., resina (mastic) the plant, including plant part) Herbal preparation(s) Powdered herbal substance Pharmaceutical form(s) Powdered herbal substance in solid dosage form for oral use Powdered herbal substance in semi-solid dosage form for cutaneous use Rapporteur(s) I Chinou Peer-reviewer M Delbò Official address Domenico Scarlattilaan 6 ● 1083 HS Amsterdam ● The Netherlands Address for visits and deliveries Refer to www.ema.europa.eu/how-to-find-us Send us a question Go to www.ema.europa.eu/contact Telephone +31 (0)88 781 6000 An agency of the European Union © European Medicines Agency, 2020. Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. Table of contents Table of contents ................................................................................................................... 2 ABBREVIATIONS .................................................................................................................... 4 1. Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 6 1.1. Description of the herbal substance(s), herbal preparation(s) or combinations thereof . 6 1.2. Search and assessment methodology ................................................................. -

Leaves and Fruits Preparations of Pistacia Lentiscus L.: a Review on the Ethnopharmacological Uses and Implications in Inflammation and Infection

antibiotics Review Leaves and Fruits Preparations of Pistacia lentiscus L.: A Review on the Ethnopharmacological Uses and Implications in Inflammation and Infection Egle Milia 1,* , Simonetta Maria Bullitta 2, Giorgio Mastandrea 3, Barbora Szotáková 4 , Aurélie Schoubben 5 , Lenka Langhansová 6 , Marina Quartu 7 , Antonella Bortone 8 and Sigrun Eick 9,* 1 Department of Medicine, Surgery and Experimental Sciences, University of Sassari, Viale San Pietro 43, 07100 Sassari, Italy 2 C.N.R., Institute for Animal Production System in Mediterranean Environment (ISPAAM), Traversa La Crucca 3, Località Baldinca, 07100 Sassari, Italy; [email protected] 3 Department of Biomedical Sciences, University of Sassari, Viale San Pietro 43/C, 07100 Sassari, Italy; [email protected] 4 Faculty of Pharmacy, Charles University, Akademika Heyrovského 1203, 50005 Hradec Králové, Czech Republic; [email protected] 5 Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Perugia, Via Fabretti, 48-06123 Perugia, Italy; [email protected] 6 Institute of Experimental Botany, Czech Academy of Sciences, Rozvojová 263, 16502 Prague, Czech Republic; [email protected] 7 Department of Biomedical Sciences, University of Cagliari, Cittadella Universitaria di Monserrato, 09042 Cagliari, Italy; [email protected] Citation: Milia, E.; Bullitta, S.M.; 8 Dental Unite, Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria di Sassari, 07100 Sassari, Italy; Mastandrea, G.; Szotáková, B.; [email protected] Schoubben, A.; Langhansová, L.; 9 Department of Periodontology, School of Dental Medicine, University of Bern, Freiburgstrasse 3, Quartu, M.; Bortone, A.; Eick, S. 3010 Bern, Switzerland Leaves and Fruits Preparations of * Correspondence: [email protected] (E.M.); [email protected] (S.E.); Pistacia lentiscus L.: A Review on the Tel.: +39-79-228437 (E.M.); +41-31-632-25-42 (S.E.) Ethnopharmacological Uses and Implications in Inflammation and Abstract: There is an increasing interest in revisiting plants for drug discovery, proving scientifically Infection.