Slotting61.Pdf (422.92

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2016 ANNUAL REPORT Inspired HEARTS Improve LIVES

2016 ANNUAL REPORT Inspired HEARTS LIVES Improve 2 Sacred Heart Foundation 2016 ANNUAL REPORT 4 DREW BAREFIELD A Champion for our Community 6 QUINT & RISHY STUDER Letter From Carol Making the Hospital a Reality CHILDREN’S MIRACLE 8 NETWORK HOSPITALS 30 Years of Partnership irst, I want to personally thank you for your support of our mission of care during the past year. 9 PANAMA CITY BEACH WALMART When we in healthcare have a vision, often it Committed to Making Miracles Happen is courage — a word derived from the French EVENT HIGHLIGHTS meaning “of heart” — that is required to bring 10 Bringing the Community Together Fthat vision to life. Indeed, our healing ministry is rooted in the courage of 12 CHARLES & SHIRLEY SIMPSON the Daughters of Charity, whose vision 101 years ago was Growing Healthcare on the Emerald Coast responsible for the first Sacred Heart Hospital. Today, we continue their legacy by ensuring that growth takes place 13 THE KUGELMAN FOUNDATION where it is most needed, as with the expansion of Sacred Heart Keeping the Legacy Alive Hospital on the Emerald Coast. Our President and CEO Susan Davis has exhibited great 14 ORDER OF THE CORNETTE GALA courage with her vision of the new Studer Family Children’s Honoring Philanthropic Leaders Hospital. This will ensure that the children of tomorrow, throughout our region, will have greater access to specialized 16 DONNA PITTMAN health care designed with a child’s needs in mind. Giving Back Like Drew Barefield, our patients and their families show amazing courage as they face surgeries and illnesses, and battle 17 DAVID SANSING through therapy and rehabilitation from, chemotherapy to Investing in Our Community’s Future cardiac care to joint replacement. -

MAY 2017 The

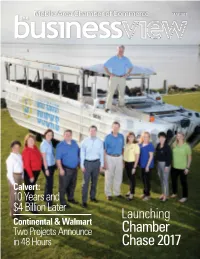

Mobile Area Chamber of Commerce MAY 2017 the Calvert: 10 Years and $4 Billion Later Launching Continental & Walmart Two Projects Announce Chamber in 48 Hours Chase 2017 the business view MAY 2017 1 We work for you. With technology, you want a partner, not a vendor. So we built the most accessible, highly responsive teams in our industry. Pair that with solutions o ering the highest levels of reliability and security and you have an ally that never stops working for you. O cial Provider of Telecommunication Solutions to the Mobile Area Chamber of Commerce Leading technology. Close to home. business solutions cspire.com/business | [email protected] | 251.459.8999 C SpireTM and C Spire Business SolutionsTM are trademarks owned by Cellular South, Inc. Cellular South, Inc. and its a liates provide products and services under the C SpireTM and C Spire Business SolutionsTM brand. 2 the©2017 business C Spire. All rightsview reserved. MAY 2017 the Mobile Area Chamber of Commerce MAY 2017 | In this issue Volume XLVIII No. 4 ON THE COVER Kevin Carey, Trustmark Bank, is at the helm, From the Publisher - Bill Sisson chairing this year’s Chamber Chase effort. His crew consists of dozens of volunteers, a few of whom are pictured with him here. Gathering and Belonging See story on pages 14-15. Photo by Jeff Tesney. 4 News You Can Use Exciting changes are taking engage in networking. place all around us. Multi- If members no longer find 8 Small Business of the Month: generational workforces have value in traditional events, Payroll Vault become the norm in work should we drop some of these 11 Kevin Carey, Trustmark Bank, to Lead places throughout the world. -

Of Counsel: Alden L

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION, ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) v. ) Civ. No. 1:07-cv-01021-PLF ) WHOLE FOODS MARKET, INC., ) REDACTED - PUBLIC VERSION ) And ) ) WILD OATS MARKETS, INC., ) ) Defendants. ) ~~~~~~~~~~~~) JOINT MEMORANDUM OF POINTS AND AUTHORITIES OF WHOLE FOODS MARKET, INC., AND WILD OATS MARKETS, INC. IN OPPOSITION TO MOTION FOR A PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION Paul T. Denis (DC Bar No. 437040) Paul H. Friedman (DC Bar No. 290635) Jeffrey W. Brennan (DC Bar No. 447438) James A. Fishkin (DC Bar No. 478958) Michael Farber (DC Bar No. 449215) Rebecca Dick (DC Bar No. 463197) DECHERTLLP 1775 I Street, N.W. Washington, DC 20006 Telephone: (202) 261-3430 Facsimile: (202) 261-3333 Of Counsel: Alden L. Atkins (DC Bar No. 393922) Neil W. Imus (DC Bar No. 394544) Roberta Lang John D. Taurman (DC Bar No. 133942) Vice-President of Legal Affairs and General Counsel VINSON & ELKINS L.L.P. Whole Foods Market, Inc. The Willard Office Building 550 Bowie Street 1455 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W., Suite 600 Austin, TX Washington, DC 20004-1008 Telephone (202) 639-6500 Facsimile (202) 639-6604 Attorneys for Whole Foods Market, Inc. Clifford H. Aronson (DC Bar No. 335182) Thomas Pak (Pro Hae Vice) Matthew P. Hendrickson (Pro Hae Vice) SKADDEN, ARPS, SLATE, MEAGHER &FLOMLLP Four Times Square NewYork,NY 10036 Telephone: (212) 735-3000 [email protected] Gary A. MacDonald (DC Bar No. 418378) SKADDEN, ARPS, SLATE, MEAGHER &FlomLLP 1440 New York Avenue, N.W. Washington, DC 20005 Telephone: (202) 371-7000 [email protected] Terrence J. Walleck (Pro Hae Vice) 2224 Pacific Dr. -

Food Distribution in the United States the Struggle Between Independents

University of Pennsylvania Law Review FOUNDED 1852 Formerly American Law Register VOL. 99 JUNE, 1951 No. 8 FOOD DISTRIBUTION IN THE UNITED STATES, THE STRUGGLE BETWEEN INDEPENDENTS AND CHAINS By CARL H. FULDA t I. INTRODUCTION * The late Huey Long, contending for the enactment of a statute levying an occupation or license tax upon chain stores doing business in Louisiana, exclaimed in a speech: "I would rather have thieves and gangsters than chain stores inLouisiana." 1 In 1935, a few years later, the director of the National Association of Retail Grocers submitted a statement to the Judiciary Committee of the House of Representatives, I Associate Professor of Law, Rutgers University School of Law. J.U.D., 1931, Univ. of Freiburg, Germany; LL. B., 1938, Yale Univ. Member of the New York Bar, 1941. This study was originally prepared under the auspices of the Association of American Law Schools as one of a series of industry studies which the Association is sponsoring through its Committee on Auxiliary Business and Social Materials for use in courses on the antitrust laws. It has been separately published and copyrighted by the Association and is printed here by permission with some slight modifications. The study was undertaken at the suggestion of Professor Ralph F. Fuchs of Indiana University School of Law, chairman of the editorial group for the industry studies, to whom the writer is deeply indebted. His advice during the preparation of the study and his many suggestions for changes in the manuscript contributed greatly to the improvement of the text. Acknowledgments are also due to other members of the committee, particularly Professors Ralph S. -

Participating Chain Pharmacies

PARTICIPATING CHAIN PHARMACIES A & P Pharmacy Discount Drug Mart Hy-Vee, Drug Town Network Pharmacy Shoppers Pharmacy ABCO Pharmacy Doc's Drugs Ingles Pharmacy Oncology Pharmacy Services Shoprite Pharmacy Acme Pharmacy Drug Emporium Integrity Healthcare Services P&C Food Market Shurfine Pharmacy Acme, Lucky, Osco, Sav-on Drug Fair Kare Pharmacy Pacmed Clinic Pharmacy Smith's Food & Drug Center Albertson's Pharmacy Duane Reade Kash N' Karry Pharmacy Pamida Pharmacy Snyder Drug Stores Allcare Pharmacy Eagle Pharmacy Kelsey Seybold Clinic Pharmacy Park Nicollet Pharmacy Southern Family Markets Ambulatory Pharmaceutical Services Edgehill Drugs Kerr Drug Pathmark Stadtlander Pharmacy Anchor Pharmacy Express, Thrift, Treasury Keystone Medicine Chest Payless Pharmacy Standard Drug Company Appletree Pharmacy Fagen Pharmacy King Kullen Pharmacy Pediatric Services of America Star Pharmacy Arrow Pharmacy Fairview Pharmacy Kinney Drug's Pharma-Card Statscript Pharmacy Aurora Pharmacy Family Care Pharmacy Kleins Supermarket Pharmacy Pharmacy Plus Steele's Pharmacy B J's Pharmacy Family Drug Klinck, Drug Barn Presbyterian Retail Pharmacy Stop & Shop Pharmacy Bakers Pharmacy Family Fare Klingensmith's Drug Price Chopper Pharmacy Super D Bartell Drugs Family Pharmacy Kmart Pharmacy Price Less Drug Super Food Mart Basha's United Drug Fedco Drug Knight Drugs Price Wise, Piggly Wiggly Super Fresh Pharmacy Bel Air Pharmacy Finast Pharmacy Kohlls Pharmacy Prime Med Pharmacy Super RX Pharmacy Big Bear Pharmacy Food 4 Less Pharmacy Kopp Drug Publix Pharmacy -

Beyond the Veterans' Benefit Known As “Aid and Attendance”

75202-1 AlaBar.qxp_Lawyer 11/2/15 8:13 AM Page 357 November 2015 | Volume 76, Number 6 Beyond the Veterans’ Benefit Known As “Aid and Attendance” Page 374 75202-1 AlaBar.qxp_Lawyer 11/2/15 8:13 AM Page 358 The best malpractice insurance takes no time to find. AIM makes it easy. Dedicated to insuring practicing attorneys. Attorneys Insurance Mutual Telephone 205-980-0009 of the South® TollFree 800-526-1246 Fax 205-980-9009 200 Inverness Parkway Birmingham, Alabama 35242 wwwAttyslnsMut .com "Insuring and Serving Practicing Attorneys Since 1989" Copyright 2013 by Attorneys In surance Mutual of the South ® 75202-1 AlaBar.qxp_Lawyer 11/2/15 8:13 AM Page 359 75202-1 AlaBar.qxp_Lawyer 11/2/15 8:14 AM Page 360 >ĂƐƚŚĂŶĐĞ^ĞŵŝŶĂƌƐĨŽƌϮϬϭϱ DECEMBER ^ĂǀĞƚŚĞĂƚĞ͊^ƚĂƌƚϮϬϭϲŽīƌŝŐŚƚǁŝƚŚ ŽŶĞŽĨŽƵƌŐƌĞĂƚƐƉƌŝŶŐƉƌŽŐƌĂŵƐ͘ 2 Alabama Update Tuscaloosa JANUARY 4 Estate Planning Birmingham 22 Professionalism Tuscaloosa Birmingham ϭϬ dĂŬŝŶŐĂŶĚĞĨĞŶĚŝŶŐĞƉŽƐŝƟŽŶƐ FEBRUARY 11 Tort Law Update Birmingham 19 Banking Law Birmingham ϭϲ ƵƐŝŶĞƐƐĂŶĚŽŵƉůĞdž>ŝƟŐĂƟŽŶBirmingham 26 Elder Law Birmingham 17 Employment Law Birmingham MAY 6-7 City & County Government 18 Alabama Update Birmingham Orange Beach 21 Trial Skills Birmingham 13 Professionalism Tuscaloosa Keep Your Library Updated with CHECK OUT OTHER Our BEST SELLING PUBLICATIONS KWWKZdhE/d/^&KZ YEAR-END CLE DĐůƌŽLJ͛ƐůĂďĂŵĂǀŝĚĞŶĐĞŝƐƚŚĞĐŽŵƉůĞƚĞĂŶĚĮŶĂůĂƵƚŚŽƌŝƚLJ regarding Alabama evidence issues for judges and lawyers alike. dŚĞŶĞǁ^ƵƉƉůĞŵĞŶƚǁŝůůďĞĂǀĂŝůĂďůĞŝŶĞĂƌůLJϮϬϭϲ͘WƌĞͲŽƌĚĞƌ tĞďĐĂƐƚƐ͗ Most of our live LJŽƵƌĐŽƉLJŶŽǁ͊ seminars will be -

2018 Baptist Health Foundation Annual Report

2018 ANNUAL REPORT Thank you for YOUR COMMUNITY Dear Friends of Mississippi Baptist Medical Center, On behalf of our patients, their families, and friends, thank you for the many generous gifts you shared with Baptist Health Foundation in 2018. Because you chose to invest in us, you have Crisler Boone made an impact on the lives of those who benefit from our Executive Director Christian healing ministry. In 2018, the Baptist Health Foundation provided much-needed 4 TRIPLETS! equipment to the hospital. Your generous gifts to our Foundation Mom Says Choosing enabled us to help the tiniest of our patients by providing Baptist Among Her bassinets, Bili-Beds (special beds used to treat infants with “Best” Decisions jaundice), and infant warmers for our well baby and neonatal ICU 5 TRAVIS DUNLAP areas. We continued our support of the Emergency Department Grateful – After Three by providing wheelchairs and beds. We funded equipment in the Close Calls area of respiratory care and cardiovascular care and purchased a 6 MARILYN TURNER leading-edge Arctic Sun® cooling device that can save the lives Lymphedema Patient of our patients who have had a stroke or heart attack. Finds Great Care and Mississippi Baptist Medical Center continues to receive Support recognition for our excellent service and care. In 2018, two of 7 BILLIE AND OSLER MOORE – our specialty areas were named by Healthgrades, America’s Giving and Receiving leading independent healthcare ratings organization, as one of 8 JEFF FINCH America’s 100 Best Hospitals for Joint Replacement Surgery and Cyclist, Turned Cancer Prostate Surgery. The Healthgrades designation for America’s Patient, Rides with a 100 Best Hospitals represents the top 2% of hospitals nationwide. -

MERGER ANTITRUST LAW Albertsons/Safeway Case Study

MERGER ANTITRUST LAW Albertsons/Safeway Case Study Fall 2020 Georgetown University Law Center Professor Dale Collins ALBERTSONS/SAFEWAY CASE STUDY Table of Contents The deal Safeway Inc. and AB Albertsons LLC, Press Release, Safeway and Albertsons Announce Definitive Merger Agreement (Mar. 6, 2014) .............. 4 The FTC settlement Fed. Trade Comm’n, FTC Requires Albertsons and Safeway to Sell 168 Stores as a Condition of Merger (Jan. 27, 2015) .................................... 11 Complaint, In re Cerberus Institutional Partners V, L.P., No. C-4504 (F.T.C. filed Jan. 27, 2015) (challenging Albertsons/Safeway) .................... 13 Agreement Containing Consent Order (Jan. 27, 2015) ................................. 24 Decision and Order (Jan. 27, 2015) (redacted public version) ...................... 32 Order To Maintain Assets (Jan. 27, 2015) (redacted public version) ............ 49 Analysis of Agreement Containing Consent Orders To Aid Public Comment (Nov. 15, 2012) ........................................................... 56 The Washington state settlement Complaint, Washington v. Cerberus Institutional Partners V, L.P., No. 2:15-cv-00147 (W.D. Wash. filed Jan. 30, 2015) ................................... 69 Agreed Motion for Endorsement of Consent Decree (Jan. 30, 2015) ........... 81 [Proposed] Consent Decree (Jan. 30, 2015) ............................................ 84 Exhibit A. FTC Order to Maintain Assets (omitted) ............................. 100 Exhibit B. FTC Order and Decision (omitted) ..................................... -

Consolidation in Food Retailing: Prospects for Consumers & Grocery Suppliers

18 Economic Research Service/USDA Agricultural Outlook/August 2000 Special Article Consolidation in Food Retailing: Prospects for Consumers & Grocery Suppliers n recent years, the U.S. food retailing industry has undergone unprecedented consolidation and structural change through Imergers, acquisitions, divestitures, internal growth, and new competitors. Since 1996, almost 3,500 supermarkets have been purchased, representing annual grocery store sales of more than $67 billion (including food and non-food sales by supermarkets, superettes, and convenience stores). Two of the largest food retailing combinations in history were announced in 1998: the merger of Albertson’s (the nation’s fourth-largest food retailer) with American Stores (the second-largest), and the acquisition of sixth-largest Fred Meyer by first-ranked Kroger Company. The recent consolidation wave has brought together food retail- ers operating within and across regions. While many food retail- ers operate in multiple regions, none is considered truly nation- wide in scope. Of the consolidations, the Albertson’s-American Stores merger, which resulted in common ownership of super- markets reaching coast to coast (but not all regions), comes clos- est to creating a nationwide food retailer. Harrison Jack Widespread consolidation in the grocery industry—driven by The share of consumers’ income spent for food-at-home, pur- expected efficiency gains from economies of size—has had a chased from foodstores and other retail outlets, continued to fall. significant effect on the share of total grocery store sales From 1992 to 1998, the share of disposable income devoted to accounted for by the largest food retailers. It also raises ques- food-at-home fell from 7.8 percent to 7.6 percent, continuing a tions about long-term trends driving these changes and the impli- long-term trend. -

2Nd Walgreens Coming to Pineville Kings Country Update

2nd Walgreens coming to Pineville The City of Pineville is pleased to welcome its second Walgreens , with the announcement of the new store to be located at the intersection of La. Highway 28 East and Edgewood Drive Extension in Pineville. The newest Walgreens will be located between Advance Auto Parts and Red River Bank . Construction is expected to begin in September and the projected opening is spring 2005. This location will be the fourth new Walgreens Drug Store in the Alexandria-Pineville area. The store, owned by Pineville Edgewood South LLC, will have 14,820 square feet with 77 parking spaces and a 24-hour drive-through window. It is expected to employ 20 to 25 people. Construction is nearing completion on the other Pineville store, which is on the corner of Pinecrest Drive and the Monroe Highway (U.S. 165) near Kings Country. Construction is also nearing completion in Alexandria on Jackson Street Extension, while another Walgreens is being built on Masonic Drive, across from Christus St. Frances Cabrini Hospital. Walgreens is the nation's largest drugstore chain and 11th largest retailer. It operates more than 4,000 drugstores in 44 states and Puerto Rico, including approximately 90 stores in Louisiana. Walgreens is returning to Central Louisiana after leaving the market several years ago. Kings Country Update The face-lift and new additions to Kings Country Shopping Center in Pineville continue to take shape. Two new stores are now open. Dollar General is located in one-third of the old Delchamps building, while Stage Department Store will occupy the other two-thirds and should be open by early October. -

James Fishkin

James A. Fishkin Partner Washington, D.C. | 1900 K Street, NW, Washington, DC, United States of America 20006-1110 T +1 202 261 3421 | F +1 202 261 3333 [email protected] Services Antitrust/Competition > Merger Clearance > Merger Litigation: U.S. > James A. Fishkin combines both government and private sector experience within his practice, which focuses on mergers and acquisitions covering a wide range of industries, including supermarket chains and other retailers, consumer and food product manufacturers, internet- based firms, chemical and industrial gas firms, and healthcare firms. He has been a key participant in several of the most significant litigated antitrust cases in the last two decades that have set important precedents, including representing Whole Foods Market, Inc. in FTC v. Whole Foods Market, Inc. and the Federal Trade Commission in FTC v. Staples, Inc. and FTC v. H.J. Heinz Co. Mr. Fishkin has also played key roles in securing unconditional clearances for many high-profile mergers, including the merger of OfficeMax/Office Depot and Monster/HotJobs, and approval for other high-profile mergers after obtaining successful settlements, including the merger of Albertsons/Safeway. He also served as the court-appointed Divestiture Trustee on behalf of the Department of Justice in the Grupo Bimbo/Sara Lee bread merger. Mr. Fishkin has been recognized by Chambers USA, The Best Lawyers in America, The Legal 500 , and Benchmark Litigation for his antitrust work. Chambers USA notes that Mr. Fishkin “impresses sources with his ‘very practical perspective,’ with commentators also describing him as ‘very analytical.’” The Legal 500 states that Mr. -

2010 Statewide Seabird and Shorebird Rooftop Nesting Survey in Florida FINAL REPORT

2010 Statewide Seabird and Shorebird Rooftop Nesting Survey in Florida FINAL REPORT RICARDO ZAMBRANO and T. NATASHA WARRAICH Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission INTRODUCTION In Florida, seabirds and shorebirds typically nest on flat beaches, sandbars, and spoil islands, which have coarse sand or shells with little to no vegetation (Thompson et al. 1997). However, habitat loss due to coastal development, an increase in human disturbance, and increased predation by native and non-native species have likely contributed to beach nesting birds such as Least Terns (Sternula antillarum), Black Skimmers (Rynchops niger), Gull-billed Terns (Gelochelidon nilotica), Roseate Terns (Sterna dougallii), and American Oystercatchers (Haematopus palliatus) increasingly nesting on tar-and- gravel roofs (Thompson et al. 1997; Zambrano et al. 2000; Douglass et al. 2001; Zambrano and Smith 2003; Lott 2006; Gore et al. 2008). A tar-and-gravel roof (hereafter a gravel roof) consists of a layer of tar spread over a roof, and then covered with a layer of gravel (DeVries and Forys 2004). This nesting behavior was first reported for Least Terns in Miami Beach, Florida in the early 1950s (J.K. Howard in Fisk 1978) and has since been recorded in Maryland, North and South Carolina, Georgia, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas (Jackson and Jackson 1985; Krogh and Schweitzer 1999; Butcher et al. 2007). In Florida, Least Terns increasingly have used roofs for nesting and now they outnumber ground nesting colonies. Zambrano et al. (1997) found 93% of Least Terns breeding in southeast Florida nested on roofs and Gore et al. (2007) found that 84% of all Least Tern nesting pairs in Florida were on roofs.