Retailer Liability in Louisiana Issues And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MAY 2017 The

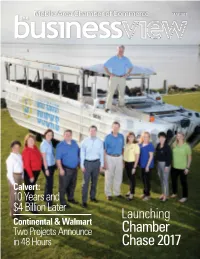

Mobile Area Chamber of Commerce MAY 2017 the Calvert: 10 Years and $4 Billion Later Launching Continental & Walmart Two Projects Announce Chamber in 48 Hours Chase 2017 the business view MAY 2017 1 We work for you. With technology, you want a partner, not a vendor. So we built the most accessible, highly responsive teams in our industry. Pair that with solutions o ering the highest levels of reliability and security and you have an ally that never stops working for you. O cial Provider of Telecommunication Solutions to the Mobile Area Chamber of Commerce Leading technology. Close to home. business solutions cspire.com/business | [email protected] | 251.459.8999 C SpireTM and C Spire Business SolutionsTM are trademarks owned by Cellular South, Inc. Cellular South, Inc. and its a liates provide products and services under the C SpireTM and C Spire Business SolutionsTM brand. 2 the©2017 business C Spire. All rightsview reserved. MAY 2017 the Mobile Area Chamber of Commerce MAY 2017 | In this issue Volume XLVIII No. 4 ON THE COVER Kevin Carey, Trustmark Bank, is at the helm, From the Publisher - Bill Sisson chairing this year’s Chamber Chase effort. His crew consists of dozens of volunteers, a few of whom are pictured with him here. Gathering and Belonging See story on pages 14-15. Photo by Jeff Tesney. 4 News You Can Use Exciting changes are taking engage in networking. place all around us. Multi- If members no longer find 8 Small Business of the Month: generational workforces have value in traditional events, Payroll Vault become the norm in work should we drop some of these 11 Kevin Carey, Trustmark Bank, to Lead places throughout the world. -

Participating Chain Pharmacies

PARTICIPATING CHAIN PHARMACIES A & P Pharmacy Discount Drug Mart Hy-Vee, Drug Town Network Pharmacy Shoppers Pharmacy ABCO Pharmacy Doc's Drugs Ingles Pharmacy Oncology Pharmacy Services Shoprite Pharmacy Acme Pharmacy Drug Emporium Integrity Healthcare Services P&C Food Market Shurfine Pharmacy Acme, Lucky, Osco, Sav-on Drug Fair Kare Pharmacy Pacmed Clinic Pharmacy Smith's Food & Drug Center Albertson's Pharmacy Duane Reade Kash N' Karry Pharmacy Pamida Pharmacy Snyder Drug Stores Allcare Pharmacy Eagle Pharmacy Kelsey Seybold Clinic Pharmacy Park Nicollet Pharmacy Southern Family Markets Ambulatory Pharmaceutical Services Edgehill Drugs Kerr Drug Pathmark Stadtlander Pharmacy Anchor Pharmacy Express, Thrift, Treasury Keystone Medicine Chest Payless Pharmacy Standard Drug Company Appletree Pharmacy Fagen Pharmacy King Kullen Pharmacy Pediatric Services of America Star Pharmacy Arrow Pharmacy Fairview Pharmacy Kinney Drug's Pharma-Card Statscript Pharmacy Aurora Pharmacy Family Care Pharmacy Kleins Supermarket Pharmacy Pharmacy Plus Steele's Pharmacy B J's Pharmacy Family Drug Klinck, Drug Barn Presbyterian Retail Pharmacy Stop & Shop Pharmacy Bakers Pharmacy Family Fare Klingensmith's Drug Price Chopper Pharmacy Super D Bartell Drugs Family Pharmacy Kmart Pharmacy Price Less Drug Super Food Mart Basha's United Drug Fedco Drug Knight Drugs Price Wise, Piggly Wiggly Super Fresh Pharmacy Bel Air Pharmacy Finast Pharmacy Kohlls Pharmacy Prime Med Pharmacy Super RX Pharmacy Big Bear Pharmacy Food 4 Less Pharmacy Kopp Drug Publix Pharmacy -

Consolidation in Food Retailing: Prospects for Consumers & Grocery Suppliers

18 Economic Research Service/USDA Agricultural Outlook/August 2000 Special Article Consolidation in Food Retailing: Prospects for Consumers & Grocery Suppliers n recent years, the U.S. food retailing industry has undergone unprecedented consolidation and structural change through Imergers, acquisitions, divestitures, internal growth, and new competitors. Since 1996, almost 3,500 supermarkets have been purchased, representing annual grocery store sales of more than $67 billion (including food and non-food sales by supermarkets, superettes, and convenience stores). Two of the largest food retailing combinations in history were announced in 1998: the merger of Albertson’s (the nation’s fourth-largest food retailer) with American Stores (the second-largest), and the acquisition of sixth-largest Fred Meyer by first-ranked Kroger Company. The recent consolidation wave has brought together food retail- ers operating within and across regions. While many food retail- ers operate in multiple regions, none is considered truly nation- wide in scope. Of the consolidations, the Albertson’s-American Stores merger, which resulted in common ownership of super- markets reaching coast to coast (but not all regions), comes clos- est to creating a nationwide food retailer. Harrison Jack Widespread consolidation in the grocery industry—driven by The share of consumers’ income spent for food-at-home, pur- expected efficiency gains from economies of size—has had a chased from foodstores and other retail outlets, continued to fall. significant effect on the share of total grocery store sales From 1992 to 1998, the share of disposable income devoted to accounted for by the largest food retailers. It also raises ques- food-at-home fell from 7.8 percent to 7.6 percent, continuing a tions about long-term trends driving these changes and the impli- long-term trend. -

2Nd Walgreens Coming to Pineville Kings Country Update

2nd Walgreens coming to Pineville The City of Pineville is pleased to welcome its second Walgreens , with the announcement of the new store to be located at the intersection of La. Highway 28 East and Edgewood Drive Extension in Pineville. The newest Walgreens will be located between Advance Auto Parts and Red River Bank . Construction is expected to begin in September and the projected opening is spring 2005. This location will be the fourth new Walgreens Drug Store in the Alexandria-Pineville area. The store, owned by Pineville Edgewood South LLC, will have 14,820 square feet with 77 parking spaces and a 24-hour drive-through window. It is expected to employ 20 to 25 people. Construction is nearing completion on the other Pineville store, which is on the corner of Pinecrest Drive and the Monroe Highway (U.S. 165) near Kings Country. Construction is also nearing completion in Alexandria on Jackson Street Extension, while another Walgreens is being built on Masonic Drive, across from Christus St. Frances Cabrini Hospital. Walgreens is the nation's largest drugstore chain and 11th largest retailer. It operates more than 4,000 drugstores in 44 states and Puerto Rico, including approximately 90 stores in Louisiana. Walgreens is returning to Central Louisiana after leaving the market several years ago. Kings Country Update The face-lift and new additions to Kings Country Shopping Center in Pineville continue to take shape. Two new stores are now open. Dollar General is located in one-third of the old Delchamps building, while Stage Department Store will occupy the other two-thirds and should be open by early October. -

James Fishkin

James A. Fishkin Partner Washington, D.C. | 1900 K Street, NW, Washington, DC, United States of America 20006-1110 T +1 202 261 3421 | F +1 202 261 3333 [email protected] Services Antitrust/Competition > Merger Clearance > Merger Litigation: U.S. > James A. Fishkin combines both government and private sector experience within his practice, which focuses on mergers and acquisitions covering a wide range of industries, including supermarket chains and other retailers, consumer and food product manufacturers, internet- based firms, chemical and industrial gas firms, and healthcare firms. He has been a key participant in several of the most significant litigated antitrust cases in the last two decades that have set important precedents, including representing Whole Foods Market, Inc. in FTC v. Whole Foods Market, Inc. and the Federal Trade Commission in FTC v. Staples, Inc. and FTC v. H.J. Heinz Co. Mr. Fishkin has also played key roles in securing unconditional clearances for many high-profile mergers, including the merger of OfficeMax/Office Depot and Monster/HotJobs, and approval for other high-profile mergers after obtaining successful settlements, including the merger of Albertsons/Safeway. He also served as the court-appointed Divestiture Trustee on behalf of the Department of Justice in the Grupo Bimbo/Sara Lee bread merger. Mr. Fishkin has been recognized by Chambers USA, The Best Lawyers in America, The Legal 500 , and Benchmark Litigation for his antitrust work. Chambers USA notes that Mr. Fishkin “impresses sources with his ‘very practical perspective,’ with commentators also describing him as ‘very analytical.’” The Legal 500 states that Mr. -

2010 Statewide Seabird and Shorebird Rooftop Nesting Survey in Florida FINAL REPORT

2010 Statewide Seabird and Shorebird Rooftop Nesting Survey in Florida FINAL REPORT RICARDO ZAMBRANO and T. NATASHA WARRAICH Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission INTRODUCTION In Florida, seabirds and shorebirds typically nest on flat beaches, sandbars, and spoil islands, which have coarse sand or shells with little to no vegetation (Thompson et al. 1997). However, habitat loss due to coastal development, an increase in human disturbance, and increased predation by native and non-native species have likely contributed to beach nesting birds such as Least Terns (Sternula antillarum), Black Skimmers (Rynchops niger), Gull-billed Terns (Gelochelidon nilotica), Roseate Terns (Sterna dougallii), and American Oystercatchers (Haematopus palliatus) increasingly nesting on tar-and- gravel roofs (Thompson et al. 1997; Zambrano et al. 2000; Douglass et al. 2001; Zambrano and Smith 2003; Lott 2006; Gore et al. 2008). A tar-and-gravel roof (hereafter a gravel roof) consists of a layer of tar spread over a roof, and then covered with a layer of gravel (DeVries and Forys 2004). This nesting behavior was first reported for Least Terns in Miami Beach, Florida in the early 1950s (J.K. Howard in Fisk 1978) and has since been recorded in Maryland, North and South Carolina, Georgia, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas (Jackson and Jackson 1985; Krogh and Schweitzer 1999; Butcher et al. 2007). In Florida, Least Terns increasingly have used roofs for nesting and now they outnumber ground nesting colonies. Zambrano et al. (1997) found 93% of Least Terns breeding in southeast Florida nested on roofs and Gore et al. (2007) found that 84% of all Least Tern nesting pairs in Florida were on roofs. -

Script Care Ltd. Participating Chain Pharmacies

SCRIPT CARE LTD. PARTICIPATING CHAIN PHARMACIES A & P Pharmacy Drug Emporium Kare Pharmacy Park Nicollet Pharmacy Shurfine Pharmacy ABCO Pharmacy Drug Fair Kash N' Karry Pharmacy Pathmark Smith's Food & Drug Center Acme Pharmacy Duane Reade Kelsey Seybold Clinic Pharmacy Payless Pharmacy Snyder Drug Stores Acme, Lucky, Osco, Sav-on Eagle Pharmacy Kerr Drug Pediatric Services of America Southern Family Markets Albertson's Pharmacy Edgehill Drugs Keystone Medicine Chest PharmacPhar-Mor Stadtlander Pharmacy Allcare Pharmacy Express, Thrift, Treasury King Kullen Pharmacy Pharma-Card Standard Drug Company Ambulatory Pharmaceutical ServiceFagen Pharmacy Kinney Drug's Pharmaca Integrative Pharmacy Star Pharmacy Anchor Pharmacy Fairview Pharmacy Kleins Supermarket Pharmacy Pharmacy Plus Statscript Pharmacy Appletree Pharmacy Family Care Pharmacy Klinck, Drug Barn Presbyterian Retail Pharmacy Steele's Pharmacy Arrow Pharmacy Family Drug Klingensmith's Drug Price Chopper Pharmacy Stop & Shop Pharmacy Aurora Pharmacy Family Fare Kmart Pharmacy Price Less Drug Super D B J's Pharmacy Family Pharmacy Knight Drugs Price Wise, Piggly Wiggly Super Food Mart Bakers Pharmacy Fedco Drug Kohlls Pharmacy Prime Med Pharmacy Super Fresh Pharmacy Bartell Drugs Finast Pharmacy Kopp Drug Publix Pharmacy Super RX Pharmacy Basha's United Drug Food 4 Less Pharmacy Kroger Pharmacy QFC Pharmacy Super Sav-On-Drug's Bel Air Pharmacy Food City Pharmacy Lewis Drugs Quality Pharmacy Supersaver Pharmacy, Sentry Drug Bi-Lo Pharmacy Food Lion Pharmacy Lifecheck Drug Quick Chek -

CEU Uncashed Check List

90's Nails Aaron's Sales And Lease/3051 Springhill ALABAMA ART SUPPLY Alice Butler Alice M Williams formally Sugars ALL AMERICAN MINI WAREHOUSE Allan Wolk frm dba Peaches Music & Video ALTUS BANK AMACCO/SUNSHINE PETRO AMERICAN CAREER SERVICES INC. APPLEBEE'S Athletic Attic Avenue #139, The B & H Food Store Baker Brothers BAMA FEVER/TIGER PRIDE BAMBOO CLUB Bargain Time #1626 Bargain Time #1636 Basta-Natural Beauty Bay City Tire & Wheel, LLC BAY COMPUTERS INC BAYSIDE BUILDERS Bellsouth Telecommunications BEST BONDING CO. Bill's Dollar Store /Moffett Bill's Dollar Store #137 BOB MANDAL NISSAN BODY REPAIRE' INC Books-A-Million #626 PineBrook BOTTOMS-UP BEL BOWDEN ELECTRIC Brandi McNutt Bruno's/BFW Liqidators LLC BRYAN'S MAGIC VIDEO BSDC Inc. Dba Steve's Off Road BUBBA'S FOOD STORE Buds Union 76/Bullocks Texaco BUDWEISER BUSCH BUSABA'S THAI CUISINE BUSCH JEWELRY COMPANY BUTTERCREAM DREAMS BAKERY C & M LOCKSMITH C.W. BRUSH CABLEVISION (MULTIVISION)(MEDIA - COM) CAFFEY'S PHARMACY Cain's B & H Food Store CASH & CARRY CASH CONNECTION/ALLEN FRANKS Central Discount Drug Store Certegy Payment Recovery Services, Inc. CHARLES STRASBURG CHERIE MILLER CHINESE PALACE CHUNCHULA GROCERY CIRCLE PIPE & SUPPLY CO,INC. CITRONELLE MARKETPLACE Clara Sharie Austin CLASSIC DESIGNS Coastal Ready Mix, LLC COCKRELL'S BODY SHOP Comcast Cable Compac Food Stores CONCORDE ENTERPRISES Consumer Foods CONTACT LENS SPECIALIST Copeland's Starvin Marvin CVS D & P AUTO WRECKERS INC. D.J'S LOUNGE DAV THIRFT STORE David Allen Discount Furniture DAVID THOMAS FURNITURE DEBRA FRANCE Deep South Burgers & More Delchamps Delchamps: Check Security Denise Jernigan Dillards DOLLAR EXPRESS Domino's Pizza # 5371 TTT Domino's Pizza # 5829 TTTDomino's Pizza Domino's Pizza #5394 Lee Schwall Domino's Pizza #5800 Domino's Pizza #5830 Juan Gomez Domino's Pizza #5831 Domino's Pizza #5832 Domino's Pizza 5833 TTT DON MCCOY & SON, INC DOROTHEA FREY DRAWDY'S CRAB COMPANY, INC. -

Slotting61.Pdf (422.92

149 FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION I N D E X PRESENTATION PAGE: MIKE WHINSTON 204 PANEL: PAGE: 2 151 3 225 4 312 5 383 For The Record, Inc. Waldorf, Maryland (301)870-8025 150 FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION In the Matter of: ) WORKSHOP ON SLOTTING ALLOWANCES. ) Volume 2 -----------------------------------) JUNE 1, 2000 Room 432 Federal Trade Commission 6th Street and Pennsylvania Ave., NW Washington, D.C. 20580 The above-entitled matter came on for panel discussion pursuant to notice, at 8:30 a.m. For The Record, Inc. Waldorf, Maryland (301)870-8025 151 PANEL 2: POTENTIAL EFFECTS OF SLOTTING ALLOWANCES: CONCERNS OVER EXCLUSION AND EXCLUSIVE DEALING PANEL 2 MODERATORS DAVID BALTO, FTC BILL COHEN, FTC NEIL AVERITT, FTC PANEL 2 GUESTS SCOTT HANNAH (Pacific Valley Foods) VICTOR THOMAS (Ahold) KEVIN HADE (Ukrop's) TOM STENZEL (UFFVA) GREG SHAFFER (Economist) JOHN EAGAN (Costco) DAVID NICKILA (Portland French Bakery) KAREN CARVER (Elan Natural Waters) JACK MCMAHON (Gallant Greeting Cards) PAMELA MILLS (Tortilla Industry Association) GUS DOPPES (California Scents Air Fresheners) MIKE WHINSTON (Economist) GREG GUNDLACH (Marketing academic) For The Record, Inc. Waldorf, Maryland (301)870-8025 152 P R O C E E D I N G S - - - - - - MR. BALTO: We're going to start promptly at 8:30. I'm David Balto. This is day 2 of the slotting allowance workshop. Today we have a busy schedule. We start off with the panel on the question of exclusion. We follow with a panel on retailer market power. Today's lunch, as I mentioned earlier, in the cafeteria on The Top of the Trade, 7th floor, is fried chicken with homemade potato salad. -

SENATE—Wednesday, April 11, 2007

April 11, 2007 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD—SENATE, Vol. 153, Pt. 6 8639 SENATE—Wednesday, April 11, 2007 The Senate met at 9:30 a.m. and was RECOGNITION OF THE be the bill we pass and send to the called to order by the Honorable BEN- REPUBLICAN LEADER President for his signature and to point JAMIN L. CARDIN, a Senator from the The ACTING PRESIDENT pro tem- out that S. 5 is truly the compromise State of Maryland. pore. The Republican leader is recog- bill. nized. I want everyone to know that. There PRAYER was some talk that S. 30 should be the f The Chaplain, Dr. Barry C. Black, of- compromise. Let me point out for clar- fered the following prayer: SCHEDULE ity that last year we passed the stem Let us pray. Mr. MCCONNELL. Mr. President, I cell research bill. There was another God of all life, we seek You in a am told the majority leader will be out bill offered on the floor at the same world filled with challenges and prob- shortly. Let me just mention that the time called the Specter-Santorum bill. lems. Prepare the Members of this body vote is likely to be moved from 5:45 to That bill was supported by the Bush for the rigors of solving life’s riddles 5:55, for the information of all Sen- administration. Both bills passed, but today. Give them the wisdom to seek ators. We have a structured order for the Specter-Santorum bill never made common opportunities, to accomplish debate for the balance of the morning it through the House, and therefore the Your divine will in our world. -

NOVEMBER 2019 The

Mobile Area Chamber of Commerce NOVEMBER 2019 the Austal Set to Launch USS Mobile Global Supply Chain Summit – Nov. 12-13 MAWSS Named Minority Business Advocate A voice solution that speaks to your business’ needs. At C Spire, we know finding the right voice solution is about more than phones. You need a crystal-clear connection to your customers. That’s why we deliver IP Voice inspired by you. With pristine voice quality, premium features, and dedicated local support and user training, you can focus on what matters most – your customers. Discover the difference with customer inspired IT. cspire.com/voip 2 the business view NOVEMBER 2019 ©2019 C Spire. All rights reserved. USS Mobile Christening History in the Making December 2019 Rebecca Byrne, Ship Sponsor Join the Build www.AustalJobs.com the business view NOVEMBER 2019 3 the Mobile Area Chamber of Commerce NOVEMBER 2019 | In this issue ON THE COVER: Austal’s new LCS – USS Mobile – is nearing completion. Learn about this special ship, and its commissioning From the Publisher - Bill Sisson taking place in December on pg. 12. Photo by LA Fotographee. Census Critical to Alabama’s Future 5 News You Can Use Every 10 years the census used to pay for critical public 9 Small Business of the Month: bureau gathers information on funding such as healthcare, Momentum IT the population of the United education, housing, and States to determine how many infrastructure such as roads 10 MAWSS Named 2019 Rev. Wesley A. representatives each state will and bridges. James Minority Business Advocate get in Congress and how tax As business leaders, we 11 Veterans Day Activities in Mobile dollars will be distributed. -

Greer's Getting Ready for Move to New Location

Serving the greater NORTH, CENTRAL AND SOUTH BALDWIN communities Crazy Donuts now open PAGE 8 RIDEYELLOW in Bay Minette The Onlooker PAGE 9 JUNE 27, 2018 | GulfCoastNewsToday.com | 75¢ Greer’s getting ready for move to new location By JOHN UNDERWOOD coincide with the move. [email protected] On Monday, June 18, the Robertsdale City Council Greer’s CashSaver Cost Plus voted unanimously to recom- is gearing up for the grand mend the approval through opening of its new location, the Alcoholic Beverrage Con- 21951 Alabama 59, Suite D, the trol Board of the transfer of former location of Winn Dixie. Greer’s retail beer and table The Greer’s family will wine license to the new loca- SUBMITTED PHOTO host a ribbon cutting with the tion. Lauren Buchanan, Library Aide Central Baldwin Chamber Officials said Monday that of Commerce on Wednesday, Greer’s planned to close its June 27 beginning at 10 a.m. Twenty years and will be running specials to SEE GREERS, PAGE 2 SUBMITTED PHOTO of Harry Potter at FPL Submitted FOLEY — On Monday, July 2, the book Harry Pot- ter and the Chamber of Secrets will have its 20th anniversary. Please join the Foley Public Library for a special Harry Potter cel- ebration. There will be a photo op- portunity from 10 a.m. – 1 p.m. in the library’s lobby. JESSICA VAUGHN / STAFF PHOTOS You can have your photo The Animal Tales “Libraries Rock” taken with the library dis- show was hosted by Animal Tales’ play which includes life size Miss Vicki, who visited the Marjo- standees of Harry, Herm- rie Younce Snook Public Library in ione, and Dobby.