International Guidance for Abu Dhabi's Modern

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

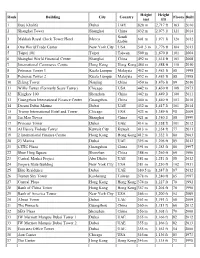

List of World's Tallest Buildings in the World

Height Height Rank Building City Country Floors Built (m) (ft) 1 Burj Khalifa Dubai UAE 828 m 2,717 ft 163 2010 2 Shanghai Tower Shanghai China 632 m 2,073 ft 121 2014 Saudi 3 Makkah Royal Clock Tower Hotel Mecca 601 m 1,971 ft 120 2012 Arabia 4 One World Trade Center New York City USA 541.3 m 1,776 ft 104 2013 5 Taipei 101 Taipei Taiwan 509 m 1,670 ft 101 2004 6 Shanghai World Financial Center Shanghai China 492 m 1,614 ft 101 2008 7 International Commerce Centre Hong Kong Hong Kong 484 m 1,588 ft 118 2010 8 Petronas Tower 1 Kuala Lumpur Malaysia 452 m 1,483 ft 88 1998 8 Petronas Tower 2 Kuala Lumpur Malaysia 452 m 1,483 ft 88 1998 10 Zifeng Tower Nanjing China 450 m 1,476 ft 89 2010 11 Willis Tower (Formerly Sears Tower) Chicago USA 442 m 1,450 ft 108 1973 12 Kingkey 100 Shenzhen China 442 m 1,449 ft 100 2011 13 Guangzhou International Finance Center Guangzhou China 440 m 1,440 ft 103 2010 14 Dream Dubai Marina Dubai UAE 432 m 1,417 ft 101 2014 15 Trump International Hotel and Tower Chicago USA 423 m 1,389 ft 98 2009 16 Jin Mao Tower Shanghai China 421 m 1,380 ft 88 1999 17 Princess Tower Dubai UAE 414 m 1,358 ft 101 2012 18 Al Hamra Firdous Tower Kuwait City Kuwait 413 m 1,354 ft 77 2011 19 2 International Finance Centre Hong Kong Hong Kong 412 m 1,352 ft 88 2003 20 23 Marina Dubai UAE 395 m 1,296 ft 89 2012 21 CITIC Plaza Guangzhou China 391 m 1,283 ft 80 1997 22 Shun Hing Square Shenzhen China 384 m 1,260 ft 69 1996 23 Central Market Project Abu Dhabi UAE 381 m 1,251 ft 88 2012 24 Empire State Building New York City USA 381 m 1,250 -

Abu Dhabi Report H22012

Abu Dhabi Report H2 2012 “2012 was a pivotal year for the Abu Dhabi real estate market with the delivery of significant new developments which have raised the quality of living and working standards in the capital. The residential sub-sectors are now becoming more clearly defined by qualitative factors with tenants seeking value for money. In 2013 we expect to see a widening segregation in rental rates between the popular new developments, which, with occupancy levels rising, will be able to sustain rental levels and in some cases achieve growth, and the less popular older stock, that will continue to see rents come under downward pressure as landlords compete to maintain occupancy.“ Paul Maisfield, Associate Director & General Manager Abu Dhabi, Asteco Property Management Abu Dhabi Supply Estimates 2012 New Supply 2013 Scheduled New Supply Average Apartment Rental Rates (AED’000/pa) Apartments (in units) 9,000 12,000 Studio 1 BR 2 BR 3 BR Villas (in units) 6,000 5,000 From To From To From To From To Offices (in m2) 312,000 290,000 Marasy -- 87 110 135 170 185 237 Marina Square 55 65 75 85 110 130 140 180 Nation Towers - - 95 100 145 170 165 300 Reef Downtown - - 55 65 70 75 85 95 Residential Market Overview Rihan Heights -- 95 122 130 150 155 190 We estimate that approximately 15,000 new homes have been delivered to the Abu Dhabi market Saadiyat Beach Apartments -- 81 128 130 163 165 206 over the course of 2012, with a further 17,000 scheduled for completion in 2013. -

Tall Buildings Tall Building Projects Worldwide

Tall buildings Safe, comfortable and sustainable solutions for skyscrapers ©China Resources Shenzhen Bay Development Co., Ltd ©China Resources Tall building projects worldwide Drawing upon our diverse skillset, Arup has helped define the skylines of our cities and the quality of urban living and working environments. 20 2 6 13 9 1 7 8 16 5 11 19 3 15 10 17 4 12 18 14 2 No. Project name Location Height (m) 1 Raffles City Chongqing 350 ©Safdie Architect 2 Burj Al Alam Dubai 510 ©The Fortune Group/Nikken Sekkei 3 UOB Plaza Singapore 274 4 Kompleks Tan Abdul Razak Penang 232 5 Kerry Centre Tianjin 333 ©Skidmore Owings & Merrill 6 CRC Headquarters Shenzhen 525 ©China Resources Shenzhen Bay Development Co Ltd 7 Central Plaza Hong Kong 374 8 The Shard London 310 9 Two International Finance Centre Hong Kong 420 10 Shenzhen Stock Exchange Shenzhen 246 ©Marcel Lam Photography 11 Wheelock Square Shanghai 270 ©Kingkay Architectural Photography 12 Riviera TwinStar Square Shanghai 216 ©Kingkay Architectural Photography 13 China Zun (Z15) Beijing 528 ©Kohn Pederson Fox Associates PC 14 HSBC Main Building Hong Kong 180 ©Vanwork Photography 15 East Pacific Centre Shenzhen 300 ©Shenzhen East Pacific Real Estate Development Co Ltd 16 China World Tower Beijing 330 ©Skidmore, Owings & Merrill 17 Commerzbank Frankfurt 260 ©Ian Lambot 18 CCTV Headquarters Beijing 234 ©OMA/Ole Scheeren & Rem Koolhaas 19 Aspire Tower Doha 300 ©Midmac-Six Construct 20 Landmark Tower Yongsan 620 ©Renzo Piano Building Workshop 21 Northeast Asia Trade Tower New Songdo City 305 ©Kohn Pedersen Fox Associates PC 22 Guangzhou International Finance Centre Guangzhou 432 ©Wilkinson Eyre 23 Torre Reforma Mexico 244 ©L Benjamin Romano Architects 24 Chow Tai Fook Centre Guangzhou 530 ©Kohn Pederson Fox Associates PC 25 Forum 66 Shenyang 384 ©Kohn Pedersen Fox Associates PC 26 Canton Tower Guangzhou 600 ©Information Based Architecture 27 30 St. -

Signature Redacted Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering May 21, 2015

TRENDS AND INNOVATIONS IN HIGH-RISE BUILDINGS OVER THE PAST DECADE ARCHIVES 1 by MASSACM I 1TT;r OF 1*KCHN0L0LGY Wenjia Gu JUL 02 2015 B.S. Civil Engineering University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2014 LIBRAR IES SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF CIVIL AND ENVIRONMENTAL ENGINEERING IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ENGINEERING IN CIVIL ENGINEERING AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY JUNE 2015 C2015 Wenjia Gu. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known of hereafter created. Signature of Author: Signature redacted Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering May 21, 2015 Certified by: Signature redacted ( Jerome Connor Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering Thesis Supervisor Accepted bv: Signature redacted ?'Hei4 Nepf Donald and Martha Harleman Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering Chair, Departmental Committee for Graduate Students TRENDS AND INNOVATIONS IN HIGH-RISE BUILDINGS OVER THE PAST DECADE by Wenjia Gu Submitted to the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering on May 21, 2015 in Partial Fulfillment of the Degree Requirements for Master of Engineering in Civil and Environmental Engineering ABSTRACT Over the past decade, high-rise buildings in the world are both booming in quantity and expanding in height. One of the most important reasons driven the achievement is the continuously evolvement of structural systems. In this paper, previous classifications of structural systems are summarized and different types of structural systems are introduced. Besides the structural systems, innovations in other aspects of today's design of high-rise buildings including damping systems, construction techniques, elevator systems as well as sustainability are presented and discussed. -

Acoustic Works for Hotels & High Rise Buildings S

P.O.Box 37670,Dubai, U.A.E. Tel: + 971 4 8857361 Fax: + 971 4 885 7362 E-mail: [email protected] ANNEXURE III LIST OF PROJECTS EXECUTED FOR ACOUSTIC WORKS FOR HOTELS & HIGH RISE BUILDINGS S. NO. PROJECT NAME HOTELS LOCATIONS HI-RISE BUILDINGS LOCATIONS 1 CROWN PLAZA STAY BRIDGE HOTEL ABU DHABI AL JAZIRA TOWERS ABU DHABI GRAND CONTINENTAL 2 FLAMINGO HOTEL ABU DHABI CONFERENCE PALACE ABU DHABI 3 IBIS NOVOTEL HOTEL ABU DHABI THE LANDMARK ABU DHABI 4 LAGOONA BEACH HOTEL ABU DHABI THE EVISION MEDIA STUDIO ABU DHABI KHALIDIYA PALACE ROTANA TEXAS & M COPLLEGE OF 5 HOTEL & RES. ABU DHABI ENGINEERING DOHA 6 THE EMERALD PALACE HOTEL & APT. ABU DHABI THE PEARL - PORTO ARABIA DOHA 7 BURJ AL ARAB DUBAI 11 TOWERS BUSINESS BAY DUBAI 8 CITYMAX HOTEL DUBAI MIRDIFF CITY CENTER DUBAI 9 CROWN PLAZA HOTEL DUBAI MARINA SCAPE DUBAI 10 IBIS NOVOTELHOTEL DUBAI BURJ DUBAI DEVELOPMENT DUBAI 11 MISSION HOTEL DUBAI THE MAZE TOWER DUBAI 12 PALM JUMEIRHA B EACH RESIDENACES DUBAI BURJ AL ARAB DUBAI 13 PPM CONRAD HOTEL DUBAI BURJ KHALIFA DUBAI 14 RITZ CARLTON-TRADE CENTER DUBAI ATLANTIS DUBAI 15 SOFITAL PALM HOTEL DUBAI MARINA APARTMENTS DUBAI 16 TAJ GRANDEUR RESIDENCES DUBAI AMERICAN SCHOOL DUBAI 17 PLAZA RESIDENTIAL DUBAI BUILDING BY DAMAN DUBAI 18 THE LOFTS @ BURJ DUBAI DUBAI BURJ AL SALAM TOWER DUBAI 19 DUBAI SILICON OASIS DUBAI JAFZA CONVENTION CENTER DUBAI 20 MOVENPICK HOTEL & SPA DUBAI MARINA CROWN DUBAI 21 HOTEL AT TECOM DUBAI MARINA SCAPE DUBAI 22 MARRIOT COURTYARD HOTEL DUBAI PALLADIUM DUBAI 23 GROSVENOR HOUSE DUBAI SILOCON OASIS DUBAI JUMEIRAH BUSINESS CENTRE 24 THE ATLANTIS PALM DUBAI TOWER DUBAI Page 1 of 2 P.O.Box 37670,Dubai, U.A.E. -

Major Projects

Home of Advanced Systems Major Projects www.almazrouicas.com 11 Cables & Accessories Emirates Palace Etihad Towers Major Projects AL DAR HQ, Al Raha Beach Ferrari World Yas Island Abu Dhabi F1 – Yas Marina Circuit, Yas Island Abu Dhabi Security Exchange – Sowwah Square Cleveland Clinic Abu Dhabi, Sowwah Island ADIA HQ (Abu Dhabi Investment Authority) Corniche Al Bahr Towers (ADIC HQ Abu Dhabi) Shams Abu Dhabi, Reem Island – Sorouh City of Lights – Reem Island Marine Square, Al Reem Island – Tamouh Al Wahda Mall & Al Wahda City (Towers) Central Market Redevelopment MIST – Masdar Institute for Science & Technology Zayed University, Khalifa City Sheikh Zayed Grand Mosque ADNEC (AD National Exhibition Centre) & Hyatt Capital Gate Tower Emirates Palace The Landmark Tower, Corniche St. Regis Resort, Al Saadiyat Khalidia Palace Hotel Al Raha Resort & Mall Al Muneera, Al Raha Beach Community Al Bustan Complex Delma Mall Project (Musaffah) Presidential Palace Cranleigh School, Sadiyat Island Yas Island Zone K ADNOC New Guest House, Ruwais Khalifa University Extension Abu Dhabi Accountability Authority Al Bustan Hospital, Mussafah Ruwais Housing Complex ADNOC Head Quarters Shah Gas Complex – Ruwais ADNOC Ruwais Villas STS - Secondary Technical School – Al Ain Louvre Abu Dhabi Etihad Towers And many more..... Sowwah Square Ferrari World AL DAR HQ, Al Raha Beach 12 www.almazrouicas.com Home of Advanced Systems Burj Khalifa Dubai Dubai Mall Al Mass Tower Mirdif City Centre, Deira city center expansion, Me’aisem City center The Opera House, Dubai, Sky view tower, Emirate flight catering Dubai world trade center Palm Jumeirah (Atlantis) Palace of H.H. the chairman of DXB municipality 11 Towers, Business Bay Motor City The Address, Downtown Dubai Festival City Dubai Festival City Grand Hayatt Hotel Fairmont Hotel Dubai Marina Dubai International Airport Dubai World Central airport Madinat Jumeirah Internet & Media City Police Headquarters Garden City MBC & Al Arabia News Studios Al Shorouk T.V,Al Dawliya T.V. -

Rank Building City Country Height (M) Height (Ft) Floors Built 1 Burj

Rank Building City Country Height (m) Height (ft) Floors Built 1 Burj Khalifa Dubai UAE 828 m 2,717 ft 163 2010 Makkah Royal Clock 2 Mecca Saudi Arabia 601 m 1,971 ft 120 2012 Tower Hotel 3 Taipei 101 Taipei Taiwan 509 m[5] 1,670 ft 101 2004 Shanghai World 4 Shanghai China 492 m 1,614 ft 101 2008 Financial Center International 5 Hong Kong Hong Kong 484 m 1,588 ft 118 2010 Commerce Centre Petronas Towers 1 6 Kuala Lumpur Malaysia 452 m 1,483 ft 88 1998 and 2 Nanjing Greenland 8 Nanjing China 450 m 1,476 ft 89 2010 Financial Center 9 Willis Tower Chicago USA 442 m 1,450 ft 108 1973 10 Kingkey 100 Shenzhen China 442 m 1,449 ft 98 2011 Guangzhou West 11 Guangzhou China 440 m 1,440 ft 103 2010 Tower Trump International 12 Chicago USA 423 m 1,389 ft 98 2009 Hotel and Tower 13 Jin Mao Tower Shanghai China 421 m 1,380 ft 88 1999 14 Al Hamra Tower Kuwait City Kuwait 413 m 1,352 ft 77 2011 Two International 15 Hong Kong Hong Kong 416 m 1,364 ft 88 2003 Finance Centre 16 23 Marina Dubai UAE 395 m 1,296 ft 89 2012[F] 17 CITIC Plaza Guangzhou China 391 m 1,283 ft 80 1997 18 Shun Hing Square Shenzhen China 384 m 1,260 ft 69 1996 19 Empire State Building New York City USA 381 m 1,250 ft 102 1931 19 Elite Residence Dubai UAE 381 m 1,250 ft 91 2012[F] 21 Tuntex Sky Tower Kaohsiung Taiwan 378 m 1,240 ft 85 1994 Emirates Park Tower 22 Dubai UAE 376 m 1,234 ft 77 2010 1 Emirates Park Tower 22 Dubai UAE 376 m 1,234 ft 77 2010 2 24 Central Plaza Hong Kong Hong Kong 374 m 1,227 ft 78 1992[C] 25 Bank of China Tower Hong Kong Hong Kong 367 m 1,205 ft 70 1990 Bank -

CTBUH 2013 Review

CTBUH Year in Review: Tall Trends of 2013 Small Increase in Completions Marks Return to Upward Trend Report by Daniel Safarik and Antony Wood, CTBUH Research by Marty Carver and Marshall Gerometta, CTBUH By all appearances, the small increase in the total number of tall-building completions from 2012 into 2013 is indicative of a return to the prevalent trend of increasing completions each year over the past decade. Perhaps 2012, with its small year-on-year drop in completions, was the last year to register the full effect of the 2008 / 2009 global financial crisis, and a small sigh of relief can be let out in the tall-building industry as we begin 2014. Figure 1. The tallest 20 buildings completed in 2013 © CTBUH Please see end of report for a more detailed 2013 skyline At the same time, it is important to note that 2013 was the second-most successful year ever, in terms of 200-meter-plus building completion, with 73 buildings of 200 meters or greater height completed. When examined in the broad course of skyscraper completions since 2000, the rate is still increasing. From 2000 to 2013, the total number of 200-meter-plus buildings in existence increased from 261 to 830 – an astounding 318 percent. From this point of view, we can more confidently estimate that the slight slowdown of 2012, which recorded 69 completions after 2011’s record 81 – was a “blip,” and that 2013 was more representative of the general upward trend. 2013 Tallest #1: JW Marriott Marquis Hotel Dubai, Dubai 2013 Tallest #4: Al Yaqoub Tower, Dubai (CC BY-NC-ND) 2013 Tallest #5: The Landmark, Abu Dhabi. -

A Postcard from Dubai - Design and Construction of Some of the Tallest Buildings in the World

ctbuh.org/papers Title: A Postcard from Dubai - Design and Construction of Some of the Tallest Buildings in the World Authors: Andy Davids, Director, Hyder Consulting Jonathan Wongso, Hyder Consulting Darko Popovic, Hyder Consulting Angus McFarlane, Hyder Consulting Subjects: Architectural/Design Construction Keywords: Concrete Construction Seismic Steel Wind Publication Date: 2008 Original Publication: CTBUH 2008 8th World Congress, Dubai Paper Type: 1. Book chapter/Part chapter 2. Journal paper 3. Conference proceeding 4. Unpublished conference paper 5. Magazine article 6. Unpublished © Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat / Andy Davids; Jonathan Wongso; Darko Popovic; Angus McFarlane A Postcard from Dubai Design and Construction of Some of the Tallest Buildings in the World Dr. Andy Davids, Jonathan Wongso, Darko Popovic and Angus McFarlane Hyder Consulting Middle East, PO Box 52750, Dubai, United Arab Emirates, Email: [email protected] Abstract This paper presents an overview of the design and construction of some of the tallest buildings in the world, currently under construction in the Gulf region. The paper explores some of the key natural and commercial forces at work in the region, and how these forces shape the design of these super high rise projects. The key natural forces of regional seismic activity and the wind environment of the Gulf are highlighted as having characteristics which are unique to the Gulf, and their effects upon the design of these tall buildings must be carefully considered in design. Typical subsurface conditions in the Gulf are outlined, and the ability of this marine sediment material to degrade under cyclic loading is highlighted. Finally, a series of postcards of mixed use towers in the height range of 450 metres to 600 metres currently under design and/or construction in the Gulf are used to illustrate the observations offered in the paper. -

New York's First

110 NEW YORK’S FIRST $100 MILLION APARTMENT IS C OMINGIn a CITy CONSUMEd by lUXURy cONDOM SOONINIUMS, no pRICe Is too hIGh To pAY. As a nEw rOUNd of eND-OF-YEAr bONUSEs hITs bANk aCCOUNTS, Michael Gross REPORTs on tHe rACe to a nINE-FIGUre sALE. 90 orget the gated motor court, the down below sit Louis Kahn’s Franklin D. Roo- private courtyard or the waterfall in sevelt Four Freedoms Park and the UN itself. the lobby and check out the dizzy- The Foster+Partners–designed condomini- ing view from atop 50 United Na- um tower is still under construction; its triplex Ftions Plaza. Manhattan’s Rocky Mountains— penthouse (complete with a 50-foot-long heated the skyscraper tops of the Empire State, the outdoor pool and a Foster-created, one-piece 80 Chrysler, Rockefeller Center and MetLife—all stainless-steel staircase—both hoisted up to the seem close enough to touch. You can see the aerie by crane) doesn’t even have walls yet. But network of bridges connecting the city to the since they will be walls of glass, the views won’t rest of the world; the East and Hudson riv- change once they’re installed. ers; the Statue of Liberty; the new One World What has changed? The asking price. Trade Center. In the distance, airplanes take When 50 UN was topped out in July 2013, 70 off from Kennedy and LaGuardia. And straight two separate apartments—a $55 million duplex 60 50 40 30 The Midtown Manhattan skyline, as seen from 56 Leonard, a 60-story condo by Herzog & de Meuron in New 20 York’s TriBeCa 10 119 and a $45 million full-floor penthouse below it—were the most ex- listings soon followed; the flag had dropped on the race to nine figures. -

Potentials and Limitations of Supertall Building Structural Systems: Guiding for Architects

POTENTIALS AND LIMITATIONS OF SUPERTALL BUILDING STRUCTURAL SYSTEMS: GUIDING FOR ARCHITECTS A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF NATURAL AND APPLIED SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY HÜSEYİN EMRE ILGIN IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN BUILDING SCIENCE IN ARCHITECTURE JULY 2018 Approval of the thesis: POTENTIALS AND LIMITATIONS OF SUPERTALL BUILDING STRUCTURAL SYSTEMS: GUIDING FOR ARCHITECTS submitted by HÜSEYİN EMRE ILGIN in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Department of Architecture, Middle East Technical University by, Prof. Dr. Halil Kalıpçılar Dean, Graduate School of Natural and Applied Sciences Prof. Dr. F. Cânâ Bilsel Head of Department, Architecture Assoc. Prof. Dr. Halis Günel Supervisor, Department of Architecture, METU Assist. Prof. Dr. Bekir Özer Ay Co-Supervisor, Department of Architecture, METU Examining Committee Members: Prof. Dr. Cüneyt Elker Department of Architecture, Çankaya University Assoc. Prof. Dr. Halis Günel Department of Architecture, METU Assoc. Prof. Dr. Ayşe Tavukçuoğlu Department of Architecture, METU Assoc. Prof. Dr. Ali Murat Tanyer Department of Architecture, METU Prof. Dr. Adile Nuray Bayraktar Department of Architecture, Başkent University Date: 03.07.2018 I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last name: Hüseyin Emre ILGIN Signature: iv ABSTRACT POTENTIALS AND LIMITATIONS OF SUPERTALL BUILDING STRUCTURAL SYSTEMS: GUIDING FOR ARCHITECTS Ilgın, H. -

Burj Khalifa Stretches a Massive 2,716.5Ft in The

FEATURE Burj Khalifa- Tallest gambling. And so it seemed, Burj Khalifa’s construction Building in the World yet prettier. began in 2004 and was I looked out, overwhelmed completed in 2010, after 22 by the artistic details in the million man-hours. At the peak DUBAI RISING designs, so many exquisite of production over 12,000 architectural wonders in one workers and contractors were ake-up I could have lazed in the posh to Burj Khalifa — the tallest observation deck, I couldn’t place. I wasn’t familiar with the on site everyday, representing calls sound living room, worked at the free building on the planet. (Dubai help but gasp at the light skyline yet, but would soon more than 100 nationalities. harsh in any WiFi equipped office, dined at a rightfully flaunts a slew of reflecting from this site. Below, come to recognize the squared Guides claim that 31,400 table recessed in a round nook, language. these superlatives.) a pea-sized city looked as arch or Financial Center, Al tons of rebar were used in the and used a second bathroom. WBut, they ring hideous when Ticketed guests enter the if I was viewing it from an Yaqoub Tower, the Big Ben skyscraper, enough to extend Instead, I slumped with jet-lag you’ve gone to bed just a tower and stroll past a series airplane, but of course, I was facsimile, and other swooping over a quarter of the way around into a magnificent king-sized few hours earlier, following of construction photos and art, not. Burj Khalifa stretches a edifices.