Necronomicon.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Extraterrestrial Places in the Cthulhu Mythos

Extraterrestrial places in the Cthulhu Mythos 1.1 Abbith A planet that revolves around seven stars beyond Xoth. It is inhabited by metallic brains, wise with the ultimate se- crets of the universe. According to Friedrich von Junzt’s Unaussprechlichen Kulten, Nyarlathotep dwells or is im- prisoned on this world (though other legends differ in this regard). 1.2 Aldebaran Aldebaran is the star of the Great Old One Hastur. 1.3 Algol Double star mentioned by H.P. Lovecraft as sidereal The double star Algol. This infrared imagery comes from the place of a demonic shining entity made of light.[1] The CHARA array. same star is also described in other Mythos stories as a planetary system host (See Ymar). The following fictional celestial bodies figure promi- nently in the Cthulhu Mythos stories of H. P. Lovecraft and other writers. Many of these astronomical bodies 1.4 Arcturus have parallels in the real universe, but are often renamed in the mythos and given fictitious characteristics. In ad- Arcturus is the star from which came Zhar and his “twin” dition to the celestial places created by Lovecraft, the Lloigor. Also Nyogtha is related to this star. mythos draws from a number of other sources, includ- ing the works of August Derleth, Ramsey Campbell, Lin Carter, Brian Lumley, and Clark Ashton Smith. 2 B Overview: 2.1 Bel-Yarnak • Name. The name of the celestial body appears first. See Yarnak. • Description. A brief description follows. • References. Lastly, the stories in which the celes- 3 C tial body makes a significant appearance or other- wise receives important mention appear below the description. -

The Dunwich Horror

The Dunwich Horror Cthulhu Mythos by Howard Phillips Lovecraft, 1890-1937 Written: 1928 Published: 1929 in »Weird Tales« J J J J J I I I I I Table of Contents I … thru … X J J J J J I I I I I “Gorgons, and Hydras, and Chimaeras—dire stories of Celaeno and the Harpies—may reproduce themselves in the brain of superstition—but they were there before. They are transcripts, types—the archetypes are in us, and eternal. How else should the recital of that which we know in a waking sense to be false come to affect us at all? Is it that we naturally conceive terror from such objects, considered in their capacity of being able to inflict upon us bodily injury? O, least of all! These terrors are of older standing. They date beyond body-or without the body, they would have been the same… That the kind of fear here treated is purely spiritual—that it is strong in proportion as it is objectless on earth, that it predominates in the period of our sinless infancy— are difficulties the solution of which might afford some probable insight into our ante-mundane condition, and a peep at least into the shadowland of pre- existence .” —Charles Lamb: Witches and Other Night-Fears In the isolated, desolate, decrepit village of Dunwich, Massachusetts, Wilbur Whateley is the hideous son of Lavinia Whateley, a deformed and unstable albino mother, and an unknown father (alluded to in passing by mad Old Whateley, as "Yog-Sothoth"). Strange events surround his birth and precocious development. -

Pandemic: Reign of Cthulhu Rulebook

Beings of ancient and bizarre intelligence, known as Old Ones, are stirring within their vast cosmic prisons. If they awake into the world, it will unleash an age of madness, chaos, and destruction upon the very fabric of reality. Everything you know and love will be destroyed! You are cursed with knowledge that the “sleeping masses” cannot bear: that this Evil exists, and that it must be stopped at all costs. Shadows danced all around the gas street light above you as the pilot flame sputtered a weak yellow light. Even a small pool of light is better than total darkness, you think to yourself. You check your watch again for the third time in the last few minutes. Where was she? Had something happened? The sound of heels clicking on pavement draws your eyes across the street. Slowly, as if the darkness were a cloak around her, a woman comes into view. Her brown hair rests in a neat bun on her head and glasses frame a nervous face. Her hands hold a large manila folder with the words INNSMOUTH stamped on the outside in blocky type lettering. “You’re late,” you say with a note of worry in your voice, taking the folder she is handing you. “I… I tried to get here as soon as I could.” Her voice is tight with fear, high pitched and fast, her eyes moving nervously without pause. “You know how to fix this?” The question in her voice cuts you like a knife. “You can… make IT go away?!” You wince inwardly as her voice raises too loudly at that last bit, a nervous edge of hysteria creeping into her tone. -

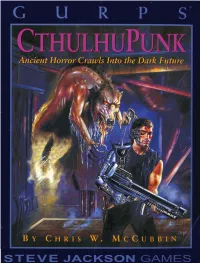

I STEVE JACKSON GAMES ,; Ancient Howor Crawls Into the Dark Future

I STEVE JACKSON GAMES ,; Ancient Howor Crawls into the Dark Future By Chris W. McCubbin Edited by Scott D. Haring Cover by Albert Slark Illustrated by Dan Smith GURPS System Design by Steve Jackson Scott Haring, Managing Editor Page Layout, Typography and Interior Production by Rick Martin Cover Production by Jeff Koke Art Direction by Lillian Butler Print Buying by Andrew Hartsock and Monica Stephens Dana Blankenship, Sales Manager Thanks to Dm Smith Additional Material by David Ellis Dickerson Bibliographic information compiled by Chris Jarocha-Emst Proofreading by Spike Y. Jones Playtesters: Bob Angell, Sean Barrett, Kaye Barry, C. Milton Beeghly, James Cloos, Mike DeSanto, Morgan Goulet, David G. Haren, Dave Magnenat, Virginia L. Nelson, James Rouse, Karen Sakamoto, Michael Sullivan and Craig Tsuchiya GURPS and the all-seeing pyramid are registered trademarks of Steve Jackson Games Incorporated. Pyramid and the names of all products published by Steve Jackson Games Incorporated are registered trademarks or trademarks of Steve Jackson Games Incorporated, or used under license. Cull of Cihulhu is a trademark of Chaosium Inc. and is used by permission. Elder Sign art (p. 55) used by permission of Chaosium Inc. GURPS CihuIhuPunk is copyright 0 1995 by Steve Jackson Games Incorporated. All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A ISBN 1-55634-288-8 Introduction ................................ 4 Central and South America ..27 Hacker ..................................43 About GURPS ............................4 The Pacific Rim ...................27 -

Dunwich Horror by Sean Branney with Andrew Leman

Dark Adventure Radio Theatre: The Dunwich Horror by Sean Branney With Andrew Leman Based on "The Dunwich Horror" by H.P. Lovecraft Read-along Script ©2008, HPLHS, Inc., all rights reserved Static, radio tuning, snippet of 30s song, more tuning, static dissolves to: Dark Adventure Radio theme music. ANNOUNCER Tales of intrigue, adventure, and the mysterious occult that will stir your imagination and make your very blood run cold. Music crescendo. ANNOUNCER This is Dark Adventure Radio Theatre, with your host Chester Langfield. Today’s episode: H.P. Lovecraft’s “The Dunwich Horror”. Music diminishes. CHESTER LANGFIELD The hills of Western Massachusetts contain dark and terrible secrets. Strange families keep to themselves and practice rites of ancient and unspeakable black magic. These dreadful and unholy rituals give birth to a monstrosity beyond imagination, a monstrosity that threatens mankind itself! Can a brave handful of intrepid scholars hope to confront the otherwordly destruction of “The Dunwich Horror”? But first a word from our sponsor. A few piano notes from the Fleur de Lys jingle. CHESTER LANGFIELD When I sit down to enjoy a meal, the first thing I do is light up a Fleur de Lys cigarette. Not only do they enhance the taste of food, Fleur de Lys aid in the digestive process. Our cigarettes are made from finer costlier tobaccos than other brands, providing you with the very best in freshness and flavor. So, for the sake of digestion, during and after meals be sure to smoke Fleur de Lys! Dark Adventure lead-in music. DART: The Dunwich Horror 2. -

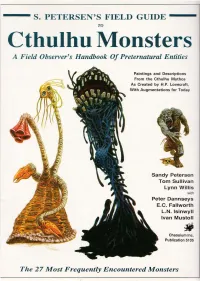

Cthulhu Monsters a Field Observer's Handbook of Preternatural Entities

--- S. PETERSEN'S FIELD GUIDE TO Cthulhu Monsters A Field Observer's Handbook Of Preternatural Entities Paintings and Descriptions From the Cthulhu Mythos As Created by H.P. Lovecraft, With Augmentations for Today Sandy Petersen Tom Sullivan Lynn Willis with Peter Dannseys E.C. Fallworth L.N. Isinwyll Ivan Mustoll Chaosium Inc. Publication 5105 The 27 Most Frequently Encountered Monsters Howard Phillips Lovecraft 1890 - 1937 t PETERSEN'S Field Guide To Cthulhu :Monsters A Field Observer's Handbook Of Preternatural Entities Sandy Petersen conception and text TOIn Sullivan 27 original paintings, most other drawings Lynn ~illis project, additional text, editorial, layout, production Chaosiurn Inc. 1988 The FIELD GUIDe is p «blished by Chaosium IIIC . • PETERSEN'S FIELD GUIDE TO CfHUU/U MONSTERS is copyrighl e1988 try Chaosium IIIC.; all rights reserved. _ Similarities between characters in lhe FIELD GUIDE and persons living or dead are strictly coincidental . • Brian Lumley first created the ChJhoniwu . • H.P. Lovecraft's works are copyright e 1963, 1964, 1965 by August Derleth and are quoted for purposes of ilIustraJion_ • IflCide ntal monster silhouelles are by Lisa A. Free or Tom SU/livQII, and are copyright try them. Ron Leming drew the illustraJion of H.P. Lovecraft QIId tlu! sketclu!s on p. 25. _ Except in this p«blicaJion and relaJed advertising, artwork. origillalto the FIELD GUIDE remains the property of the artist; all rights reserved . • Tire reproductwn of material within this book. for the purposes of personal. or corporaJe profit, try photographic, electronic, or other methods of retrieval, is prohibited . • Address questions WId commel11s cOlICerning this book. -

Mi-Go 1 Mi-Go

Mi-go 1 Mi-go An interpretation of the Mi-Go by Ruud Dirven Mi-go ("The Abominable Ones") is a Himalayan nickname for a race of extraterrestrials in the Cthulhu Mythos created by H. P. Lovecraft and others. The name was first applied to the creatures in Lovecraft's short story "The Whisperer in Darkness" (1931), elaborating on a reference to 'What fungi sprout in Yuggoth' in his sonnet cycle Fungi from Yuggoth (1929–30) which described the contrasting vegetation on alien dream-worlds. Summary The "Mi-go" are large, pinkish, fungoid, crustacean-like entities the size of a man; where a head would be, they have a "convoluted ellipsoid" composed of pyramided, fleshy rings and covered in antennae. According to two reports in the original short story, their bodies consist of a form of matter that does not occur naturally on Earth; for this reason, they do not register on ordinary photographic film. They are capable of going into suspended animation until softened and reheated by the sun or some other source of heat. They are about five feet (1.5 m) long, and their crustacean-like bodies bear numerous sets of paired appendages. They possess a pair of membranous bat-like wings which are used to fly through the "aether" of outer space (a scientific concept which is now discredited). The wings do not function well on Earth. Several other races in Lovecraft's Mythos also have wings like these. The Mi-go can transport humans from Earth to Pluto (and beyond) and back again by removing the subject's brain and placing it into a "brain cylinder", which can be attached to external devices to allow it to see, hear, and speak. -

The Weird and Monstrous Names of HP Lovecraft Christopher L Robinson HEC-Paris, France

names, Vol. 58 No. 3, September, 2010, 127–38 Teratonymy: The Weird and Monstrous Names of HP Lovecraft Christopher L Robinson HEC-Paris, France Lovecraft’s teratonyms are monstrous inventions that estrange the sound patterns of English and obscure the kinds of meaning traditionally associ- ated with literary onomastics. J.R.R. Tolkien’s notion of linguistic style pro- vides a useful concept to examine how these names play upon a distance from and proximity to English, so as to give rise to specific historical and cultural connotations. Some imitate the sounds and forms of foreign nomen- clatures that hold “weird” connotations due to being linked in the popular imagination with kabbalism and decadent antiquity. Others introduce sounds-patterns that lie outside English phonetics or run contrary to the phonotactics of the language to result in anti-aesthetic constructions that are awkward to pronounce. In terms of sense, teratonyms invite comparison with the “esoteric” words discussed by Jean-Jacques Lecercle, as they dimi- nish or obscure semantic content, while augmenting affective values and heightening the reader’s awareness of the bodily production of speech. keywords literary onomastics, linguistic invention, HP Lovecraft, twentieth- century literature, American literature, weird fiction, horror fiction, teratology Text Cult author H.P. Lovecraft is best known as the creator of an original mythology often referred to as the “Cthulhu Mythos.” Named after his most popular creature, this mythos is elaborated throughout Lovecraft’s poetry and fiction with the help of three “devices.” The first is an outlandish array of monsters of extraterrestrial origin, such as Cthulhu itself, described as “vaguely anthropoid [in] outline, but with an octopus-like head whose face was a mass of feelers, a scaly, rubbery-looking body, prodigious claws on hind and fore feet, and long, narrow wings behind” (1963: 134). -

Hypersphere Anonymous

Hypersphere Anonymous This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. ISBN 978-1-329-78152-8 First edition: December 2015 Fourth edition Part 1 Slice of Life Adventures in The Hypersphere 2 The Hypersphere is a big fucking place, kid. Imagine the biggest pile of dung you can take and then double-- no, triple that shit and you s t i l l h a v e n ’ t c o m e c l o s e t o o n e octingentillionth of a Hypersphere cornerstone. Hell, you probably don’t even know what the Hypersphere is, you goddamn fucking idiot kid. I bet you don’t know the first goddamn thing about the Hypersphere. If you were paying attention, you would have gathered that it’s a big fucking 3 place, but one thing I bet you didn’t know about the Hypersphere is that it is filled with fucked up freaks. There are normal people too, but they just aren’t as interesting as the freaks. Are you a freak, kid? Some sort of fucking Hypersphere psycho? What the fuck are you even doing here? Get the fuck out of my face you fucking deviant. So there I was, chilling out in the Hypersphere. I’d spent the vast majority of my life there, in fact. It did contain everything in my observable universe, so it was pretty hard to leave, honestly. At the time, I was stressing the fuck out about a fight I had gotten in earlier. I’d been shooting some hoops when some no-good shithouses had waltzed up to me and tried to make a scene. -

Errata for H. P. Lovecraft: the Fiction

Errata for H. P. Lovecraft: The Fiction The layout of the stories – specifically, the fact that the first line is printed in all capitals – has some drawbacks. In most cases, it doesn’t matter, but in “A Reminiscence of Dr. Samuel Johnson”, there is no way of telling that “Privilege” and “Reminiscence” are spelled with capitals. THE BEAST IN THE CAVE A REMINISCENCE OF DR. SAMUEL JOHNSON 2.39-3.1: advanced, and the animal] advanced, 28.10: THE PRIVILEGE OF REMINISCENCE, the animal HOWEVER] THE PRIVILEGE OF 5.12: wondered if the unnatural quality] REMINISCENCE, HOWEVER wondered if this unnatural quality 28.12: occurrences of History and the] occurrences of History, and the THE ALCHEMIST 28.20: whose famous personages I was] whose 6.5: Comtes de C——“), and] Comtes de C— famous Personages I was —”), and 28.22: of August 1690 (or] of August, 1690 (or 6.14: stronghold for he proud] stronghold for 28.32: appear in print.”), and] appear in the proud Print.”), and 6.24: stones of he walls,] stones of the walls, 28.34: Juvenal, intituled “London,” by] 7.1: died at birth,] died at my birth, Juvenal, intitul’d “London,” by 7.1-2: servitor, and old and trusted] servitor, an 29.29: Poems, Mr. Johnson said:] Poems, Mr. old and trusted Johnson said: 7.33: which he had said had for] which he said 30.24: speaking for Davy when others] had for speaking for Davy when others 8.28: the Comte, the pronounced in] the 30.25-26: no Doubt but that he] no Doubt that Comte, he pronounced in he 8.29: haunted the House of] haunted the house 30.35-36: to the Greater -

Lovecraft Patrons

Lovecraft Patrons Subclasses Specific to Various Great Old Ones of the Cthulhu Mythos By Zach Hitzeroth DUNGEONS & DRAGONS, D&D, Wizards of the Coast, Forgotten Realms, the dragon ampersand, Player’s Handbook, Monster Manual, Dungeon Master’s Guide, D&D Adventurers League, all other Wizards of the Coast product names, and their respective logos are trademarks of Wizards of the Coast in the USA and other countries. All characters and their distinctive likenesses are property of Wizards of the Coast. This material is protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America. Any reproduction or unauthorized use of the material or artwork contained herein is prohibited without the express written permission Sampleof Wizards of the Coast. file ©2020 Wizards of the Coast LLC, PO Box 707, Renton, WA 98057-0707, USA. Manufactured by Hasbro SA, Rue Emile-Boéchat 31, 2800 Delémont, CH. Represented by Hasbro Europe, 4 The Square, Stockley Park, Uxbridge, Middlesex, UB11 1ET, UK. Note on Expanded Spell Lists Player's Handbook Only Spells Spells marked with an asterisk are from Xanathar's 4th Level: fabricate Guide to Everything. If your DM does not allow these spells, alternate spells from the Player's Handbook can be found at the end of each subclass. Abhoth Also known as the Source of Uncleanliness, Abhoth is an Outer God depicted as an ooze or slime from which monsters and unnamable horrors crawl from. Followers of Abhoth tend to spread disease and carry oozes around with them to symbolize their patron. Expanded Spell List Abhoth lets you choose from an expanded list of spells when you learn a warlock spell. -

H. P. Lovecraft-A Bibliography.Pdf

X-'r Art Hi H. P. LOVECRAFT; A BIBLIOGRAPHY compiled by Joseph Payne/ Brennan Yale University Library BIBLIO PRESS 1104 Vermont Avenue, N. W. Washington 5, D. C. Revised edition, copyright 1952 Joseph Payne Brennan Original from Digitized by GOO UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA L&11 vie 2. THE SHUNNED HOUSE. Athol, Mass., 1928. bds., labels, uncut. o. p. August Derleth: "Not a published book. Six or seven copies hand bound by R. H. Barlow in 1936 and sent to friends." Some stapled in paper covers. A certain number of uncut, unbound but folded sheets available. Following is an extract from the copyright notice pasted to the unbound sheets: "Though the sheets of this story were printed and marked for copyright in 1928, the story was neither bound nor cir- culated at that time. A few copies were bound, put under copyright, and circulated by R. H. Barlow in 1936, but the first wide publication of the story was in the magazine, WEIRD TALES, in the following year. The story was orig- inally set up and printed by the late W. Paul Cook, pub- lisher of THE RECLUSE." FURTHER CRITICISM OF POETRY. Press of Geo. G. Fetter Co., Louisville, 1952. 13 p. o. p. THE CATS OF ULTHAR. Dragonfly Press, Cassia, Florida, 1935. 10 p. o. p. Christmas, 1935. Forty copies printed. LOOKING BACKWARD. C. W. Smith, Haverhill, Mass., 1935. 36 p. o. p. THE SHADOW OVER INNSMOUTH. Visionary Press, Everett, Pa., 1936. 158 p. o. p. Illustrations by Frank Utpatel. The only work of the author's which was published in book form during his lifetime.