Lovecraft Country

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![[Read] Lovecraft Country | PDF Books](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7544/read-lovecraft-country-pdf-books-187544.webp)

[Read] Lovecraft Country | PDF Books

Critically acclaimed cult novelist Matt Ruff makes visceral the terrors of life in Jim Crow America and its lingering effects in this brilliant and wondrous work of the imagination that melds historical fiction, pulp noir, and Lovecraftian horror and fantasy.Chicago, 1954. When his father, Montrose, goes missing, twenty-two-year-old army veteran Atticus Turner embarks on a road trip to New England to find him, accompanied by his uncle George--publisher of The Safe Negro Travel Guide--and his childhood friend, Letitia. On their journey to the manor of Mr. Braithwhite--heir to the estate that owned one of Atticus' ancestors--they encounter both mundane terrors of white America and malevolent spirits that seem straight out of the weird tales George devours.At the manor, Atticus discovers his father in chains, held prisoner by a secret cabal named the Order of the Ancient Dawn--led by Samuel Braithwhite and his son Caleb--which has gathered to orchestrate a ritual that shockingly centers on Atticus. And his one hope of salvation may be the seed of his clan's destruction.A chimerical blend of magic, power, hope, and freedom that stretches across time, touching diverse members of two black families, Lovecraft Country is a devastating kaleidoscopic portrait of racism--the terrifying specter that continues to haunt us today. Lovecraft Country by Matt Ruff, Read PDF Lovecraft Country Online, Read PDF Lovecraft Country, Full PDF Lovecraft Country, All Ebook Lovecraft Country, PDF and EPUB Lovecraft Country, PDF ePub Mobi Lovecraft Country, Reading -

Pandemic: Reign of Cthulhu Rulebook

Beings of ancient and bizarre intelligence, known as Old Ones, are stirring within their vast cosmic prisons. If they awake into the world, it will unleash an age of madness, chaos, and destruction upon the very fabric of reality. Everything you know and love will be destroyed! You are cursed with knowledge that the “sleeping masses” cannot bear: that this Evil exists, and that it must be stopped at all costs. Shadows danced all around the gas street light above you as the pilot flame sputtered a weak yellow light. Even a small pool of light is better than total darkness, you think to yourself. You check your watch again for the third time in the last few minutes. Where was she? Had something happened? The sound of heels clicking on pavement draws your eyes across the street. Slowly, as if the darkness were a cloak around her, a woman comes into view. Her brown hair rests in a neat bun on her head and glasses frame a nervous face. Her hands hold a large manila folder with the words INNSMOUTH stamped on the outside in blocky type lettering. “You’re late,” you say with a note of worry in your voice, taking the folder she is handing you. “I… I tried to get here as soon as I could.” Her voice is tight with fear, high pitched and fast, her eyes moving nervously without pause. “You know how to fix this?” The question in her voice cuts you like a knife. “You can… make IT go away?!” You wince inwardly as her voice raises too loudly at that last bit, a nervous edge of hysteria creeping into her tone. -

Inverting Lovecraft Transcript

1 You’re listening to Imaginary Worlds, a show about how we create them and why we suspend our disbelief. I’m Eric Molinsky. When I first read that HBO was going to adapt the 2016 novel Lovecraft Country into a show, I was really excited. The story imagines what if the demonic entities from H.P. Lovecraft’s fiction were a manifestation of racism in the 1950s. CLIP: TRAILER The novel that the show is based on was written by a white author, Matt Ruff, but the creative team behind the show is mostly Black, including the executive producers Jordan Peele and Misha Green. And Lovecraft Country isn’t the only work that re-imagines Lovecraft’s world from the point of view of people of color. AMC is developing a show based on the novella, The Ballad of Black Tom, where Victor LaValle reimagines a 1927 Lovecraft story with a Black protagonist. NK Jemison’s most recent novel The City We Became uses Lovecraftian horror as a metaphor for white gentrification. There’s even a role-playing game called Harlem Unbound by Darker Hue Studios, which takes the popular role-playing game, Call of Cthulhu, and re-imagines it with Black protagonists. What’s so interesting about this trend is that Lovecraft himself was exceptionally racist. So, why does his work feel so relevant now to the type of people that he feared and despised? Before we get into that, let’s back up in case, you don’t know much about Howard P. Lovecraft. He was born in 1890. -

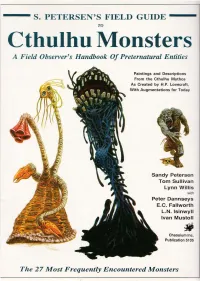

Cthulhu Monsters a Field Observer's Handbook of Preternatural Entities

--- S. PETERSEN'S FIELD GUIDE TO Cthulhu Monsters A Field Observer's Handbook Of Preternatural Entities Paintings and Descriptions From the Cthulhu Mythos As Created by H.P. Lovecraft, With Augmentations for Today Sandy Petersen Tom Sullivan Lynn Willis with Peter Dannseys E.C. Fallworth L.N. Isinwyll Ivan Mustoll Chaosium Inc. Publication 5105 The 27 Most Frequently Encountered Monsters Howard Phillips Lovecraft 1890 - 1937 t PETERSEN'S Field Guide To Cthulhu :Monsters A Field Observer's Handbook Of Preternatural Entities Sandy Petersen conception and text TOIn Sullivan 27 original paintings, most other drawings Lynn ~illis project, additional text, editorial, layout, production Chaosiurn Inc. 1988 The FIELD GUIDe is p «blished by Chaosium IIIC . • PETERSEN'S FIELD GUIDE TO CfHUU/U MONSTERS is copyrighl e1988 try Chaosium IIIC.; all rights reserved. _ Similarities between characters in lhe FIELD GUIDE and persons living or dead are strictly coincidental . • Brian Lumley first created the ChJhoniwu . • H.P. Lovecraft's works are copyright e 1963, 1964, 1965 by August Derleth and are quoted for purposes of ilIustraJion_ • IflCide ntal monster silhouelles are by Lisa A. Free or Tom SU/livQII, and are copyright try them. Ron Leming drew the illustraJion of H.P. Lovecraft QIId tlu! sketclu!s on p. 25. _ Except in this p«blicaJion and relaJed advertising, artwork. origillalto the FIELD GUIDE remains the property of the artist; all rights reserved . • Tire reproductwn of material within this book. for the purposes of personal. or corporaJe profit, try photographic, electronic, or other methods of retrieval, is prohibited . • Address questions WId commel11s cOlICerning this book. -

The Weird and Monstrous Names of HP Lovecraft Christopher L Robinson HEC-Paris, France

names, Vol. 58 No. 3, September, 2010, 127–38 Teratonymy: The Weird and Monstrous Names of HP Lovecraft Christopher L Robinson HEC-Paris, France Lovecraft’s teratonyms are monstrous inventions that estrange the sound patterns of English and obscure the kinds of meaning traditionally associ- ated with literary onomastics. J.R.R. Tolkien’s notion of linguistic style pro- vides a useful concept to examine how these names play upon a distance from and proximity to English, so as to give rise to specific historical and cultural connotations. Some imitate the sounds and forms of foreign nomen- clatures that hold “weird” connotations due to being linked in the popular imagination with kabbalism and decadent antiquity. Others introduce sounds-patterns that lie outside English phonetics or run contrary to the phonotactics of the language to result in anti-aesthetic constructions that are awkward to pronounce. In terms of sense, teratonyms invite comparison with the “esoteric” words discussed by Jean-Jacques Lecercle, as they dimi- nish or obscure semantic content, while augmenting affective values and heightening the reader’s awareness of the bodily production of speech. keywords literary onomastics, linguistic invention, HP Lovecraft, twentieth- century literature, American literature, weird fiction, horror fiction, teratology Text Cult author H.P. Lovecraft is best known as the creator of an original mythology often referred to as the “Cthulhu Mythos.” Named after his most popular creature, this mythos is elaborated throughout Lovecraft’s poetry and fiction with the help of three “devices.” The first is an outlandish array of monsters of extraterrestrial origin, such as Cthulhu itself, described as “vaguely anthropoid [in] outline, but with an octopus-like head whose face was a mass of feelers, a scaly, rubbery-looking body, prodigious claws on hind and fore feet, and long, narrow wings behind” (1963: 134). -

Lovecraft, New Materialism and the Maeriality of Writing Brad Tabas

Reading in the chtuhulucene: lovecraft, new materialism and the maeriality of writing Brad Tabas To cite this version: Brad Tabas. Reading in the chtuhulucene: lovecraft, new materialism and the maeriality of writing. Motifs, la revue HCTI, HCTI-Université de Bretagne occidentale, Brest, 2017. hal-02052305 HAL Id: hal-02052305 https://hal-ensta-bretagne.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02052305 Submitted on 28 Feb 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Motifs n° 2 (2017), Matérialité et Écriture READING IN THE CHTUHULUCENE: LOVECRAFT, NEW MATERIALISM AND THE MATERIALITY OF WRITING GIVING LIFE BACK TO MATTER The traditional take on the theme of the materiality of writing asks about the meaning of the material that supports human-made signs. It considers the importance of the dark side of the signifier; of all that one does not take into account when one sees a sign as a sign. It might consider the ways in which written words present one with multiple possible significations, the ways in which the fact of a text’s having been written haunts readers’ engagements with that text. Traditional theorists of the materiality of writing might remind us that this materia- lity really does have a signification, that paper and pixels really do convey meaning. -

Errata for H. P. Lovecraft: the Fiction

Errata for H. P. Lovecraft: The Fiction The layout of the stories – specifically, the fact that the first line is printed in all capitals – has some drawbacks. In most cases, it doesn’t matter, but in “A Reminiscence of Dr. Samuel Johnson”, there is no way of telling that “Privilege” and “Reminiscence” are spelled with capitals. THE BEAST IN THE CAVE A REMINISCENCE OF DR. SAMUEL JOHNSON 2.39-3.1: advanced, and the animal] advanced, 28.10: THE PRIVILEGE OF REMINISCENCE, the animal HOWEVER] THE PRIVILEGE OF 5.12: wondered if the unnatural quality] REMINISCENCE, HOWEVER wondered if this unnatural quality 28.12: occurrences of History and the] occurrences of History, and the THE ALCHEMIST 28.20: whose famous personages I was] whose 6.5: Comtes de C——“), and] Comtes de C— famous Personages I was —”), and 28.22: of August 1690 (or] of August, 1690 (or 6.14: stronghold for he proud] stronghold for 28.32: appear in print.”), and] appear in the proud Print.”), and 6.24: stones of he walls,] stones of the walls, 28.34: Juvenal, intituled “London,” by] 7.1: died at birth,] died at my birth, Juvenal, intitul’d “London,” by 7.1-2: servitor, and old and trusted] servitor, an 29.29: Poems, Mr. Johnson said:] Poems, Mr. old and trusted Johnson said: 7.33: which he had said had for] which he said 30.24: speaking for Davy when others] had for speaking for Davy when others 8.28: the Comte, the pronounced in] the 30.25-26: no Doubt but that he] no Doubt that Comte, he pronounced in he 8.29: haunted the House of] haunted the house 30.35-36: to the Greater -

H. P. Lovecraft-A Bibliography.Pdf

X-'r Art Hi H. P. LOVECRAFT; A BIBLIOGRAPHY compiled by Joseph Payne/ Brennan Yale University Library BIBLIO PRESS 1104 Vermont Avenue, N. W. Washington 5, D. C. Revised edition, copyright 1952 Joseph Payne Brennan Original from Digitized by GOO UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA L&11 vie 2. THE SHUNNED HOUSE. Athol, Mass., 1928. bds., labels, uncut. o. p. August Derleth: "Not a published book. Six or seven copies hand bound by R. H. Barlow in 1936 and sent to friends." Some stapled in paper covers. A certain number of uncut, unbound but folded sheets available. Following is an extract from the copyright notice pasted to the unbound sheets: "Though the sheets of this story were printed and marked for copyright in 1928, the story was neither bound nor cir- culated at that time. A few copies were bound, put under copyright, and circulated by R. H. Barlow in 1936, but the first wide publication of the story was in the magazine, WEIRD TALES, in the following year. The story was orig- inally set up and printed by the late W. Paul Cook, pub- lisher of THE RECLUSE." FURTHER CRITICISM OF POETRY. Press of Geo. G. Fetter Co., Louisville, 1952. 13 p. o. p. THE CATS OF ULTHAR. Dragonfly Press, Cassia, Florida, 1935. 10 p. o. p. Christmas, 1935. Forty copies printed. LOOKING BACKWARD. C. W. Smith, Haverhill, Mass., 1935. 36 p. o. p. THE SHADOW OVER INNSMOUTH. Visionary Press, Everett, Pa., 1936. 158 p. o. p. Illustrations by Frank Utpatel. The only work of the author's which was published in book form during his lifetime. -

HP Lovecraft: His Racism in Context

HP Lovecraft: His Racism in Context HP Lovecraft There is no question that HP Lovecraft, influential writer of horror fiction and son of Providence, held views that were clearly racist, outdated outliers even by the standards of his time. My goal here is not to excuse his racism, but to place it in a context of Lovecraft as a human being with very real flaws. I do not believe it is possible to separate the man from his work: Lovecraft the man was afraid of nearly everything unfamiliar, and that discomfort – dread, really – of the “other” is what permeates and distinguishes the world view expressed in his fiction. As does every horror writer, he exaggerated his own irrational fears in his stories: his phobia of seafood manifests, one might conclude, in his siting the lair of Cthulhu in the lost city of R’lyeh sunken under the Pacific Ocean. To what extent Lovecraft’s social and political views influenced his created universe is the subject of the title essay in Lovecraft and a World in Transition, a collection by Lovecraft scholar and biographer ST Joshi. Are Lovecraft’s space aliens and other-worldly creatures proxies or stand-ins for humans of color? Lovecraft Country by Matt Ruff is a 2016 novel that satirically explores that question, following an African-American protagonist who is a fan of Lovecraft in the era of Jim Crow. Nearly every writer critical of Lovecraft on this ground cites as the prime example of his racism a particular poem supposedly written by him in 1912, but I regard that attribution of authorship as doubtful. -

The Haunts and Hauntings of HP Lovecraft

Reanimating Providence: The Haunts and Hauntings of H. P. Lovecraft Isaac Schlecht To H. P. Lovecraft, one of the founding masters of American horror, Providence, Rhode Island was not just his lifelong home, but the inspiration for his greatest fl ights of fi ction — a vista at the border of light and dark, magic and science, hope and fear. With Lovecraft as our guide, we embark on a haunting journey through the Providence of not just his life — but our own. http://dl.lib.brown.edu/cob Copyright © 2010 Isaac Schlecht Written in partial fulfi llment of requirements for E. Taylor’s EL18 or 118: “Tales of the Real World” in the Nonfi ction Writing Program, Department of English, Brown University. Reanimating Providence: The Haunts and Hauntings of H.P. Lovecraft Isaac Schlecht October 2010 To H.P. Lovecraft, one of the founding masters of American horror, Providence, Rhode Island was not just his lifelong home, but the inspiration for his greatest flights of fiction—a vista at the border of light and dark, magic and science, hope and fear. With Lovecraft as our guide, we embark on a haunting journey through the Providence of not just his life—but our own. I never can be tied to raw, new things, For I first saw the light in an old town, Where from my window huddled roofs sloped down To a quaint harbor rich with visionings. Streets with carved doorways where the sunset beams Flooded old fanlights and small window-panes, And Georgian steeples topped with gilded vanes— These were the sights that shaped my childhood dreams. -

Necronomicon to Celebrate Horror Writer Lovecraft

In searching the publicly accessible web, we found a webpage of interest and provide a snapshot of it below. Please be advised that this page, and any images or links in it, may have changed since we created this snapshot. For your convenience, we provide a hyperlink to the current webpage as part of our service. Page 1 of 2 NecronomiCon to Celebrate Horror Writer Lovecraft NecronomiCon to celebrate work, influence of early 20th century horror writer HP Lovecraft By MICHELLE R. SMITH Associated Press The Associated Press PROVIDENCE, R.I. If you've enjoyed the works of Stephen King, seen the films "Alien" or "Prometheus," or heard about the fictional Arkham Asylum in Batman, thank H.P. Lovecraft, the early 20th century horror writer whose work has been an inspiration to others for nearly a century. The mythos Lovecraft created in stories such as "The Call of Cthulhu," ''The Case of Charles Dexter Ward" and "At the Mountains of Madness," has reached its tentacles deep into popular culture, so much that his creations and the works they inspired may be better known than the Providence writer himself. Lovecraft's fans want to give the writer his due, and this month are holding what they say is the largest celebration ever of his work and influence. It's billed the "NecronomiCon," named after a Lovecraft creation: a book that was so dark and terrible that a person could barely read a few pages before going insane. The Aug. 22-25 convention is being held in Providence, where he lived and died — poor and obscure — at age 46 in 1937. -

The Nyarlathotep Papers

by Larry DiTillio and Lynn Willis with Geoff Gillan, Kevin A. Ross, Thomas W. Phinney, Michael MacDonald, Sandy Petersen, Penelope Love Art by Lee Gibbons, Nick Smith, Tom Sullivan, Jason Eckhardt Design by Mark Schumann, Mike Blum, Thomas W. Phinney, Yurek Chodak, Shannon Appel Project and Editorial by Lynn Willis Interior Layout by Shannon Appel and Meghan McLean Cover Layout by Charlie Krank Copyreading by Janice Sellers, Alan Glover, Rob Heinsoo Chaosium is Lynn Willis, Charlie Krank, Dustin Wright, Fergie, William Jones, Meghan McLean, Nick Nacario, and Andy Dawson Chaosium Inc. 2010 The Clear Credit Box Larry DiTillio wrote the first draft of Chapters One through Six, except as noted below. The conception, plot, and essential Masks of Nyarlathotep Fourth Edition execution are entirely his, and remain a is published by Chaosium Inc. roleplaying classic. Lynn Willis rewrote the succeeding drafts, originating the his- torical background, introducing race as a Masks of Nyarlathotep Fourth Edition theme, inserting or adjusting certain char- is copyright © 1984, 1989, 1996, 2001, 2006, 2010 acters, writing the introductory chapter, by Chaosium Inc. and most of the advice, asides, incidental jokes, etc., and as an afterthought added All rights reserved. the appendix concerning what might be done with shipboard time. In the introduc- Call of Cthulhu® is the registered trademark of Chaosium Inc. tory chapter, Michael MacDonald wrote the original version of the sidebar concern- ing shipboard travel times and costs. Similarities between characters in Masks of Nyarlathotep Thomas W. Phinney set forth the back- Fourth Edition and persons living or dead are ground chronology of the campaign, and strictly coincidental.