International Regimes: Lessons from Inductive Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Expression of Orientations in Time and Space With

The Expression of Orientations in Time and Space with Flashbacks and Flash-forwards in the Series "Lost" Promotor: Auteur: Prof. Dr. S. Slembrouck Olga Berendeeva Master in de Taal- en Letterkunde Afstudeerrichting: Master Engels Academiejaar 2008-2009 2e examenperiode For My Parents Who are so far But always so close to me Мои родителям, Которые так далеко, Но всегда рядом ii Acknowledgments First of all, I would like to thank Professor Dr. Stefaan Slembrouck for his interest in my work. I am grateful for all the encouragement, help and ideas he gave me throughout the writing. He was the one who helped me to figure out the subject of my work which I am especially thankful for as it has been such a pleasure working on it! Secondly, I want to thank my boyfriend Patrick who shared enthusiasm for my subject, inspired me, and always encouraged me to keep up even when my mood was down. Also my friend Sarah who gave me a feedback on my thesis was a very big help and I am grateful. A special thank you goes to my parents who always believed in me and supported me. Thanks to all the teachers and professors who provided me with the necessary baggage of knowledge which I will now proudly carry through life. iii Foreword In my previous research paper I wrote about film discourse, thus, this time I wanted to continue with it but have something new, some kind of challenge which would interest me. After a conversation with my thesis guide, Professor Slembrouck, we decided to stick on to film discourse but to expand it. -

LOST the Official Show Auction

LOST | The Auction 156 1-310-859-7701 Profiles in History | August 21 & 22, 2010 572. JACK’S COSTUME FROM THE EPISODE, “THERE’S NO 574. JACK’S COSTUME FROM PLACE LIKE HOME, PARTS 2 THE EPISODE, “EGGTOWN.” & 3.” Jack’s distressed beige Jack’s black leather jack- linen shirt and brown pants et, gray check-pattern worn in the episode, “There’s long-sleeve shirt and blue No Place Like Home, Parts 2 jeans worn in the episode, & 3.” Seen on the raft when “Eggtown.” $200 – $300 the Oceanic Six are rescued. $200 – $300 573. JACK’S SUIT FROM THE EPISODE, “THERE’S NO PLACE 575. JACK’S SEASON FOUR LIKE HOME, PART 1.” Jack’s COSTUME. Jack’s gray pants, black suit (jacket and pants), striped blue button down shirt white dress shirt and black and gray sport jacket worn in tie from the episode, “There’s Season Four. $200 – $300 No Place Like Home, Part 1.” $200 – $300 157 www.liveauctioneers.com LOST | The Auction 578. KATE’S COSTUME FROM THE EPISODE, “THERE’S NO PLACE LIKE HOME, PART 1.” Kate’s jeans and green but- ton down shirt worn at the press conference in the episode, “There’s No Place Like Home, Part 1.” $200 – $300 576. JACK’S SEASON FOUR DOCTOR’S COSTUME. Jack’s white lab coat embroidered “J. Shephard M.D.,” Yves St. Laurent suit (jacket and pants), white striped shirt, gray tie, black shoes and belt. Includes medical stetho- scope and pair of knee reflex hammers used by Jack Shephard throughout the series. -

Jack's Costume from the Episode, "There's No Place Like - 850 H

Jack's costume from "There's No Place Like Home" 200 572 Jack's costume from the episode, "There's No Place Like - 850 H... 300 Jack's suit from "There's No Place Like Home, Part 1" 200 573 Jack's suit from the episode, "There's No Place Like - 950 Home... 300 200 Jack's costume from the episode, "Eggtown" 574 - 800 Jack's costume from the episode, "Eggtown." Jack's bl... 300 200 Jack's Season Four costume 575 - 850 Jack's Season Four costume. Jack's gray pants, stripe... 300 200 Jack's Season Four doctor's costume 576 - 1,400 Jack's Season Four doctor's costume. Jack's white lab... 300 Jack's Season Four DHARMA scrubs 200 577 Jack's Season Four DHARMA scrubs. Jack's DHARMA - 1,300 scrub... 300 Kate's costume from "There's No Place Like Home" 200 578 Kate's costume from the episode, "There's No Place Like - 1,100 H... 300 Kate's costume from "There's No Place Like Home" 200 579 Kate's costume from the episode, "There's No Place Like - 900 H... 300 Kate's black dress from "There's No Place Like Home" 200 580 Kate's black dress from the episode, "There's No Place - 950 Li... 300 200 Kate's Season Four costume 581 - 950 Kate's Season Four costume. Kate's dark gray pants, d... 300 200 Kate's prison jumpsuit from the episode, "Eggtown" 582 - 900 Kate's prison jumpsuit from the episode, "Eggtown." K... 300 200 Kate's costume from the episode, "The Economist 583 - 5,000 Kate's costume from the episode, "The Economist." Kat.. -

LOST Fandom and Everyday Philosophy

"Accidental Intellectuals": LOST Fandom and Everyday Philosophy Author: Abigail Letak Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/2615 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2012 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! This thesis is dedicated to everyone who has ever been obsessed with a television show. Everyone who knows that adrenaline rush you get when you just can’t stop watching. Here’s to finding yourself laughing and crying along with the characters. But most importantly, here’s to shows that give us a break from the day-to-day milieu and allow us to think about the profound, important questions of life. May many shows give us this opportunity as Lost has. Acknowledgements First and foremost I would like to thank my parents, Steve and Jody, for their love and support as I pursued my area of interest. Without them, I would not find myself where I am now. I would like to thank my advisor, Juliet Schor, for her immense help and patience as I embarked on combining my personal interests with my academic pursuits. Her guidance in methodology, searching the literature, and general theory proved invaluable to the completion of my project. I would like to thank everyone else who has provided support for me throughout the process of this project—my friends, my professors, and the Presidential Scholars Program. I’d like to thank Professor Susan Michalczyk for her unending support and for believing in me even before I embarked on my four years at Boston College, and for being the one to initially point me in the direction of sociology. -

{PDF} Night Lost

NIGHT LOST PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Lyn Viehl | 304 pages | 09 Oct 2008 | Penguin Putnam Inc | 9780451221025 | English | New York, United States Night Lost PDF Book I liked that she is a very strong female character and basically gets along fine without Gabriel. It is a great read that could stand alone but I suggest reading her previous novels which introduce all the characters. Jul 04, Ladiibbug rated it really liked it. And there is a steep price paid for the use of Old Magick! Archived from the original on November 13, I voice my hopes here because guys, there are 2 more books confirmed to wrap up this series. What path lies ahead of Aphrodite, now that she has her new Mark? She is fascinating and I simply liked her. While reading this book, however, I got more and more convinced that it was actually the most ingenious way P. Audio help More spoken articles. As much as I loved Zoey, she truly Received a copy from the publisher for review. The second timeline, called the "flash-sideways" narrative, follows the lives of the main characters in a setting where Oceanic never crashed, though additional changes are revealed as other characters are shown living completely different lives than they did. I can't really argue that her "human" characters are interesting and she has tallent. Readers also enjoyed. Now reading them and I'm older, though I still like the series, the only challenge for me is getting past some of the language. Shannon's departure eight episodes into season two made way for newcomers Mr. -

10 Lost Wanted

Wanted updated 03-12-13 LOST Season 1 Missing: Oceanic 815 Puzzle Cards (1:11 packs) M1 Charlie: Get it? Hurley: Dude, quit asking me Walkabout M3 Claire: I'm having contractions. Jack: How man Pilot Pt. 1 M4 Jack: Come on. Come on! Come on! Come on! Big Pilot Pt. 1 M5 Jack: We must have been at about forth thousan Pilot Pt. 1 M6 Michael: Hey, hey, where you going, man? Walt: Walkabout M7 Charlie: How does something like that happen? Pilot Pt. 1 M8 Pilot: Six hours in, our radio went out. No on Pilot Pt. 1 M9 Kate: Jack! Jack: There's someone else still o White Rabbit Numbers Die-Cut Cards (1:17 packs) 15 Sawyer: That what I think it is? Michael: Some Exodus, Pt. 2 23 Kate: I wanted you to make sure that Ray Mulle Tabula Rasa 42 Hurley: ...Stop! What are you doing?! Why'd yo Exodus, Pt. 2 Autograph Cards (1:36 packs) A-1 Evangeline Lilly as Kate Austen A-2 Josh Holloway as James "Sawyer" Ford A-3 Maggie Grace as Shannon Rutherford A-5 Mira Furlan as Danielle Rousseau A-6 William Mapother as Ethan Rom A-7 John Terry as Dr. Christian Shephard A-9 Daniel Roebuck as Dr. Leslie Arzt A-11 Kevin Tighe as Anthony Cooper A-12 Swoosie Kurtz as Emily Annabeth Locke AR1 (Redemption Card) Pieceworks Cards (1:36 packs) PW-1 Shirt worn by Evangeline Lilly as Kate Austen The Greater Good PW-2 T-shirt worn by Josh Holloway as Sawyer Ford Pilot PW-3 Top worn by Maggie Grace as Shannon Rutherford Hearts and Minds PW-4 T-shirt worn by Matthew Fox as Jack Shepherd All the Best Cowboys Have Daddy Issues PW-5 T-shirt worn by Dominic Monaghan as Charlie Pace Pilot PW-6 T-shirt worn by Terry O'Quinn as John Locke Numbers PW-8 T-shirt worn by Jorge Garcia as Hugo "Hurley" Reyes Hearts and Mind PW-10 Top worn by Yunjin Kim as Sun Kwon Exodus Pt. -

The Etiology of Character Realization, Within Rhetorical Analysis of the Series

i Found: The Etiology of Character Realization, within Rhetorical Analysis of the Series LOST, through the Application of Underhill’s and Turner’s Classic Concepts of the Mystic Journey ____________________________________________ Presented to the Faculty Liberty University School of Communication Studies ______________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Arts in Communication By Lacey L. Mitchell 2 December 2010 ii Liberty University School of Communication Master of Arts in Communication Studies Michael P. Graves Ph.D., Chair Carey Martin Ph.D., Reader Todd Smith M.F.A, Reader iii Dedication For James and Mildred Renfroe, and Donald, Kim and Chase Mitchell, without whom this work would have been remiss. I am forever grateful for your constant, unwavering support, exemplary resolve, and undiscouraged love. iv Acknowledgements This work represents the culmination of a remarkable journey in my life. Therefore, it is paramount that I recognize several individuals I found to be indispensible. First, I would like to thank my thesis chair, Dr. Michael Graves, for taking this process and allowing it to be a learning and growing experience in my own journey, providing me with unconventional insight, and patiently answering my never ending list of inquiries. His support through this process pushed me towards a completed work – Thank you. I also owe a great debt to the readers on my committee, Dr. Cary Martin and Todd Smith, who took time to ensure the completion of the final product. I will always have immense gratitude for my family. Each of them has an incredible work ethic and drive for life that constantly pushes me one step further. -

The Vilcek Foundation Celebrates a Showcase Of

THE VILCEK FOUNDATION CELEBRATES A SHOWCASE OF THE INTERNATIONAL ARTISTS AND FILMMAKERS OF ABC’S HIT SHOW EXHIBITION CATALOGUE BY EDITH JOHNSON Exhibition Catalogue is available for reference inside the gallery only. A PDF version is available by email upon request. Props are listed in the Exhibition Catalogue in the order of their appearance on the television series. CONTENTS 1 Sun’s Twinset 2 34 Two of Sun’s “Paik Industries” Business Cards 22 2 Charlie’s “DS” Drive Shaft Ring 2 35 Juliet’s DHARMA Rum Bottle 23 3 Walt’s Spanish-Version Flash Comic Book 3 36 Frozen Half Wheel 23 4 Sawyer’s Letter 4 37 Dr. Marvin Candle’s Hard Hat 24 5 Hurley’s Portable CD/MP3 Player 4 38 “Jughead” Bomb (Dismantled) 24 6 Boarding Passes for Oceanic Airlines Flight 815 5 39 Two Hieroglyphic Wall Panels from the Temple 25 7 Sayid’s Photo of Nadia 5 40 Locke’s Suicide Note 25 8 Sawyer’s Copy of Watership Down 6 41 Boarding Passes for Ajira Airways Flight 316 26 9 Rousseau’s Music Box 6 42 DHARMA Security Shirt 26 10 Hatch Door 7 43 DHARMA Initiative 1977 New Recruits Photograph 27 11 Kate’s Prized Toy Airplane 7 44 DHARMA Sub Ops Jumpsuit 28 12 Hurley’s Winning Lottery Ticket 8 45 Plutonium Core of “Jughead” (and sling) 28 13 Hurley’s Game of “Connect Four” 9 46 Dogen’s Costume 29 14 Sawyer’s Reading Glasses 10 47 John Bartley, Cinematographer 30 15 Four Virgin Mary Statuettes Containing Heroin 48 Roland Sanchez, Costume Designer 30 (Three intact, one broken) 10 49 Ken Leung, “Miles Straume” 30 16 Ship Mast of the Black Rock 11 50 Torry Tukuafu, Steady Cam Operator 30 17 Wine Bottle with Messages from the Survivor 12 51 Jack Bender, Director 31 18 Locke’s Hunting Knife and Sheath 12 52 Claudia Cox, Stand-In, “Kate 31 19 Hatch Painting 13 53 Jorge Garcia, “Hugo ‘Hurley’ Reyes” 31 20 DHARMA Initiative Food & Beverages 13 54 Nestor Carbonell, “Richard Alpert” 31 21 Apollo Candy Bars 14 55 Miki Yasufuku, Key Assistant Locations Manager 32 22 Dr. -

From William Golding's Lord of the Flies to ABC's LOST. By

Humanity Square One: From William Golding’s Lord of the Flies to ABC’s LOST. by Antonia Iliadou A dissertation to the Department of American Literature and Culture, School of English, Faculty of Philosophy of Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. Aristotle University of Thessaloniki September 2013 Humanity Square One: From William Golding’s Lord of the Flies to ABC’s LOST. by Antonia Iliadou Has been approved September 2013 APPROVED: _________________________ _________________________ _________________________ Supervisory Committee ACCEPTED: _______________ Department Chairperson Iliadou 1 CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .......................................................................................................1 ABSTRACT...............................................................................................................................3 INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................................5 CHAPTER 1: William Golding’s Lord of the Flies: Analysis and Contextualization ..............1 1.1. a. Lord of the Flies in an age of ambiguity: The position of Golding’s novel in the Post War United States...........................................................................................................2 1.1. b. The Impact of Golding’s Lord of the Flies on its Readers........................................14 1.2. “… The picture of man, at once heroic and sick”: The Depiction -

Key Scenes for 'Lost' Finale Filmed at Honolulu Catholic School

Key scenes for ‘Lost’ finale filmed at Honolulu Catholic school HONOLULU – The gateway to heaven is through the chapel doors at Sacred Hearts Academy in Honolulu. Or so one could argue after watching the series finale of the ABC-TV show “Lost” in late May. Several key scenes in the last episode were shot at the all-girls Catholic school. The finale’s penultimate scene showed the major characters from the TV show’s six seasons reuniting after their deaths in a church before “moving on” to another life, as character Christian Shephard called it in the episode, named “The End.” It is Shephard who opens the main church doors, guarded on each side by an angel statue. Through the doors comes a blazing stream of light that fills the church and engulfs all of the waiting characters. Several other scenes in the episode showed a coffin arriving at the front of the school grounds, characters talking in a lunch pavilion area outside the chapel, and Shephard and his son, Jack, talking in an office just outside the church. Despite an attempt to make the scenes seem nondenominational, with Christian and Jack Shephard talking in an office filled with world religious symbols and a multi- faith stained-glass window, many TV critics and fans have interpreted the church to be a sort of purgatory and all of the characters as moving on to heaven, a very Christian ending to “Lost.” Sacred Hearts Academy has a few “Lost” fans on its faculty and staff, who never missed an episode and were thrilled to see their school featured so prominently in the “Lost” finale. -

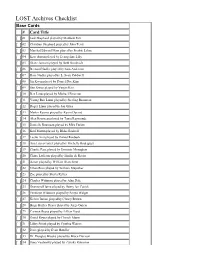

LOST Archives Checklist

LOST Archives Checklist Base Cards # Card Title [ ] 01 Jack Shephard played by Matthew Fox [ ] 02 Christian Shephard played by John Terry [ ] 03 Marshal Edward Mars played by Fredric Lehne [ ] 04 Kate Austin played by Evangeline Lilly [ ] 05 Diane Janssen played by Beth Broderick [ ] 06 Bernard Nadler played by Sam Anderson [ ] 07 Rose Nadler played by L. Scott Caldwell [ ] 08 Jin Kwon played by Daniel Dae Kim [ ] 09 Sun Kwon played by Yunjin Kim [ ] 10 Ben Linus played by Michael Emerson [ ] 11 Young Ben Linus played by Sterling Beaumon [ ] 12 Roger Linus played by Jon Gries [ ] 13 Martin Keamy played by Kevin Durand [ ] 14 Alex Rousseau played by Tania Raymonde [ ] 15 Danielle Rousseau played by Mira Furlan [ ] 16 Karl Martin played by Blake Bashoff [ ] 17 Leslie Arzt played by Daniel Roebuck [ ] 18 Ana Lucia Cortez played by Michelle Rodriguez [ ] 19 Charlie Pace played by Dominic Monaghan [ ] 20 Claire Littleton played by Emilie de Ravin [ ] 21 Aaron played by William Blanchette [ ] 22 Ethan Rom played by William Mapother [ ] 23 Zoe played by Sheila Kelley [ ] 24 Charles Widmore played by Alan Dale [ ] 25 Desmond Hume played by Henry Ian Cusick [ ] 26 Penelope Widmore played by Sonya Walger [ ] 27 Kelvin Inman played by Clancy Brown [ ] 28 Hugo Hurley Reyes played by Jorge Garcia [ ] 29 Carmen Reyes played by Lillian Hurst [ ] 30 David Reyes played by Cheech Marin [ ] 31 Libby Smith played by Cynthia Watros [ ] 32 Dave played by Evan Handler [ ] 33 Dr. Douglas Brooks played by Bruce Davison [ ] 34 Ilana Verdansky played by Zuleika -

"Lost" As an Example of the Orphic Mysteries: a Thematic Analysis

UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations 1-1-2008 "Lost" as an example of the orphic mysteries: A thematic analysis Rachael Wax University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/rtds Repository Citation Wax, Rachael, ""Lost" as an example of the orphic mysteries: A thematic analysis" (2008). UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations. 2435. http://dx.doi.org/10.25669/n2lv-18ci This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LOST AS AN EXAMPLE OF THE ORPHIC MYSTERIES: A THEMATIC ANALYSIS by Rachael Wax Bachelor of Arts University of Nevada, Las Vegas May 2006 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Master of Arts Degree in Journalism and Media Studies Hank Greenspun School of Journalism and Media Studies Greenspun College of Urban Affairs Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas December 2008 UMI Number: 1463538 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted.