Beyond Sumi-E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Simple Origami for Cub Scouts and Leaders

SIMPLE ORIGAMI FOR CUB SCOUTS AND LEADERS Sakiko Wehrman (408) 296-6376 [email protected] ORIGAMI means paper folding. Although it is best known by this Japanese name, the art of paper folding is found all over Asia. It is generally believed to have originated in China, where paper- making methods were first developed two thousand years ago. All you need is paper (and scissors, sometimes). You can use any kind of paper. Traditional origami patterns use square paper but there are some patterns using rectangular paper, paper strips, or even circle shaped paper. Typing paper works well for all these projects. Also try newspaper, gift-wrap paper, or magazine pages. You may even want to draw a design on the paper before folding it. If you want to buy origami paper, it is available at craft stores and stationary stores (or pick it up at Japan Town or China Town when you go there on a field trip). Teach the boys how to make a square piece from a rectangular sheet. Then they will soon figure out they can keep going, making smaller and smaller squares. Then they will be making small folded trees or cups! Standard origami paper sold at a store is 15cm x 15 cm (6”x6”) but they come as small as 4cm (1.5”) and as large as 24cm (almost 9.5”). They come in different colors either single sided or double sided. They also come in different patterns, varying from traditional Japanese patterns to sparkles. When you make an origami, take your time. -

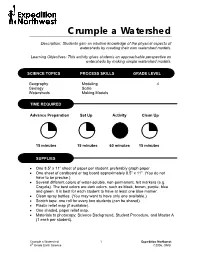

Crumple a Watershed

Crumple a Watershed Description: Students gain an intuitive knowledge of the physical aspects of watersheds by creating their own watershed models. Learning Objectives: This activity gives students an approachable perspective on watersheds by making simple watershed models. SCIENCE TOPICS PROCESS SKILLS GRADE LEVEL Geography Modeling 4 Geology Scale Watersheds Making Models TIME REQUIRED Advance Preparation Set Up Activity Clean Up 15 minutes 15 minutes 60 minutes 15 minutes SUPPLIES • One 8.5” x 11” sheet of paper per student, preferably graph paper. • One sheet of cardboard or tag board approximately 8.5” x 11”. (You do not have to be precise.) • Several different colors of water-soluble, non-permanent, felt markers (e.g. Crayola). The best colors are dark colors, such as black, brown, purple, blue and green. It is best for each student to have at least one blue marker. • Clean spray bottles. (You may want to have only one available.) • Scotch tape, one roll for every two students (can be shared). • Plastic relief map (if available). • One shaded, paper relief map. • Materials to photocopy: Science Background, Student Procedure, and Master A (1 each per student). Crumple a Watershed 1 Expedition Northwest 4th Grade Earth Science ©2006, OMSI ADVANCE PREPARATION • Fill clean spray bottles with tap water. • Cut the cardboard or tag board to size, approximately 8.5” x 11”. • Find a plastic relief map to use as an example, they are relatively inexpensive and can be found for every region of the state. • Find a paper, shaded relief map, also to be used as an example. You may want to cut one up to hand out a section to each student. -

Waste Paper Derived Biochar for Sustainable Printing Products Staples Sustainable Innovation Laboratory Project SSIL16-002

Waste Paper Derived Biochar for Sustainable Printing Products Staples Sustainable Innovation Laboratory Project SSIL16-002 Final Report Period of Performance: May 16, 2016 – December 31, 2017 Steven T. Barber and Thomas A. Trabold (PI) Golisano Institute for Sustainability Rochester Institute of Technology 1 A. Executive Summary Rationale for Research The Golisano Institute for Sustainability (GIS) at the Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT) performed a research and development assessment in conjunction with the Staples Sustainable Innovation Laboratory (SSIL) to determine the potential of pyrolyzed waste paper as a novel, cost- effective, environmentally friendly and sustainable black pigment for use in common consumer and commercial printing applications (e.g. inkjet, lithography and flexography). To do so, the primary focus of the project was the creation and testing of a stable form of elemental carbon called “biochar” (BC) to replace the heavy fuel oil derived “carbon black” (CB) pigment ubiquitously used in inks since the late 1800’s. Reducing the use of CB would lessen the demand for fossil fuels, decrease printing’s environmental impact and potentially save money since biochars are typically created from free or low cost waste feedstocks which would ordinarily be disposed. Prior published scientific research and patents demonstrated that biochars could be successfully made from box cardboard, paper towels and glossy paper. If paper waste biochars could then be successfully transformed into a sustainable black ink pigment replacement, significant commercial potential exists since the global printing ink market is forecasted to reach $23.8 billion by 2023 and consumers would like the option of a more ‘green’ alternative. -

Viimeinen Päivitys 8

Versio 20.10.2012 (222 siv.). HÖYRY-, TEOLLISUUS- JA LIIKENNEHISTORIAA MAAILMALLA. INDUSTRIAL AND TRANSPORTATION HERITAGE IN THE WORLD. (http://www.steamengine.fi/) Suomen Höyrykoneyhdistys ry. The Steam Engine Society of Finland. © Erkki Härö [email protected] Sisältöryhmitys: Index: 1.A. Höyry-yhdistykset, verkostot. Societies, Associations, Networks related to the Steam Heritage. 1.B. Höyrymuseot. Steam Museums. 2. Teollisuusperinneyhdistykset ja verkostot. Industrial Heritage Associations and Networks. 3. Laajat teollisuusmuseot, tiedekeskukset. Main Industrial Museums, Science Centres. 4. Energiantuotanto, voimalat. Energy, Power Stations. 5.A. Paperi ja pahvi. Yhdistykset ja verkostot. Paper and Cardboard History. Associations and Networks. 5.B. Paperi ja pahvi. Museot. Paper and Cardboard. Museums. 6. Puusepänteollisuus, sahat ja uitto jne. Sawmills, Timber Floating, Woodworking, Carpentry etc. 7.A. Metalliruukit, metalliteollisuus. Yhdistykset ja verkostot. Ironworks, Metallurgy. Associations and Networks. 7.B. Ruukki- ja metalliteollisuusmuseot. Ironworks, Metallurgy. Museums. 1 8. Konepajateollisuus, koneet. Yhdistykset ja museot. Mechanical Works, Machinery. Associations and Museums. 9.A. Kaivokset ja louhokset (metallit, savi, kivi, kalkki). Yhdistykset ja verkostot. Mining, Quarrying, Peat etc. Associations and Networks. 9.B. Kaivosmuseot. Mining Museums. 10. Tiiliteollisuus. Brick Industry. 11. Lasiteollisuus, keramiikka. Glass, Clayware etc. 12.A. Tekstiiliteollisuus, nahka. Verkostot. Textile Industry, Leather. Networks. -

2020 Cannabis Catalog

1 Your Complete Source for Tagging • Labeling • Printing One Source for your in-house printing needs • Stock Thermal Labels & Tags • Stock Laser Labels & Tags • Printers • Printer Accessories • Custom Labels & Tags We are Proud to be a Leader in Environmentally Aware Tags & Labels • Please See our Web Site for detailed Information Support • Tech support on all problems with printers & software What's new . Never-out Policy • New series of Color printers from Epson the • If you’ve ever been out of tags, ask about our C6000 Series Contract Orders — we can store your tags • Improved rigidity on new Envirostake in our warehouse — allocated to you for a full • Free Remote Install on all new printers season and only invoiced as we ship • Expanded selection of inkjet labels Service for Epson and other inkjet printers • Premier service for WestHort Datamax printers • Simplified pricing same for ALL COLORS • Tune-up program - keep your printer running • Introducing Stone Labels for production in top shape • Introducing Hemp labels for retail THE WESTHORT ADVANTAGE Product Index Supplies The WestHort Advantage . 1 Wrap-Around Tags: Side-to-Side..........6 Printing Services......................2 Wrap-Around Tags: End-to-End .........6-7 Thermal Printers ......................3 Pot Stakes .........................8-9 Inkjet Printers . 3 Poly Adhesive Labels ...............10-11 Label Design Software . 4 Plug Labels . 11 LABELMATE Printing Accessories . 4 Inkjet Tags & Labels . .12-13 Inkjet Ink............................5 Reference Information.................13 Ribbons ............................5 Stone and Hemp Labels ...............14 westhort.com / 800.200.8023 Let Us Customize Your Labels and Tags! 2 Wrap-Around Tree Tags We offer custom printed wrap-around tree tags. -

City of St. Louis Park Zero Waste Packaging Ordinance Chapter 12

City of St. Louis Park Zero Waste Packaging Ordinance May 17, 2016 Zero Waste Packaging Background • Nov. 2014 to May 2015 – • December 21, 2015 – After Discussed research, goals, public hearings, adoption of process for considering ordinance policy • July to Nov. 2015 – Industry • January 1, 2017 – Ordinance and local stakeholder input, becomes effective draft ordinance discussion Legislative Purpose/Goals • Sec.12.201: To increase traditional recycling and organics recycling while reducing waste and environmental impact from non-reusable, non-recyclable, and non-compostable food and beverage packaging Ordinance Requirements 1. Food establishments required to use “Zero Waste Packaging” for food prepared and served on-site or packaged to-go Must be: Excludes: Reusable or Returnable . Foods pre-packaged by Recyclable * manufacturer/producer/distributor Compostable * . Plastic knives/forks/spoons . Plastic films less than ten mils thick *Recyclable and Compostable packaging require development of acceptable material lists by city Ordinance Requirements 2. Food establishments required to provide on-site recycling and/or organics recycling for customers dining-in Development of Acceptable Packaging Materials • Lists is reviewed and approved by Council annually – Recyclable and compostable packaging meeting definitions in 12.202 – Exemptions for packaging in 12.206 Acceptable Recyclable Packaging Materials Food or beverage containers that are: • Made of recyclable material • Accepted by local material recovery facilities • Marketed to existing -

Brown Paper Goods Company 2016 STOCK PRODUCT CATALOG

Page 1 Brown Paper Goods Company 2016 STOCK PRODUCT CATALOG Manufacturers of Specialty Bags & Sheets for the Food Service Industry Since 1918 3530 Birchwood Drive Waukegan, IL 60085-8334 Phone (800) 323-9099 Fax (847) 688-1458 www.brownpapergoods.com BROWN PAPER GOODS CATALOG 2015 Page 2 CONTENTS 2 CONTENTS GENERAL INFORMATION 3 TERMS AND CONDITIONS PAN LINER 4 BAKING PAN LINERS 5 PLAIN WRAPS FLAT WRAP 6 PRINTED WRAPS 7 FOIL WRAPS INTERFOLD 8 INTERFOLDED SHEETS 9 POPCORN BAGS 10 PIZZA BAGS 11 HOT DOG AND SUB BAGS BAGS - FAST FOOD 12 FOIL HOT DOG AND SANDWICH BAGS 13 FRENCH FRY BAGS 14 PLAIN SANDWICH BAGS 15 PRINTED SANDWICH BAGS 16 WHITE MG & WAXED BREAD BAGS BAGS - BAKERY BREAD 17 PRINTED BREAD BAGS 18 NATURAL PANEL BAGS 19 WAXSEAL AUTOMATIC BAKERY BAGS BAGS - S.O.S AUTOMATIC STYLE 20 CARRY OUT SACKS & SCHOOL LUNCH BAGS BAGS - COFFEE / CANDY 21 COFFEE / CANDY DUPLEX AUTOMATIC BAGS BAGS - DELI DUPLEX CARRY-OUT 22 A LA CARTE CARRY-OUT DELI BAGS 23 STEAK PAPER DISPLAY SHEETS 24 STEAK PAPER ROLLS 25 WHITE BUTCHER & TABLE COVER ROLLS ROLLS AND DELI SHEETS 26 FREEZER ROLLS 27 PATTY PAPERS - BUTCHER SHEETS 28 NATURAL BUTCHER, & MARKET ROLLS 29 DOGGIE - CANDY BAGS - GIBLET BAGS TABLE TOP - HOSPITALITY - GIBLET 30 NAPKIN RING BANDS 31 SILVERWARE BAGS - JAN SAN - HOSPITALITY ITEMS 32 GLASSINE BAGS GLASSINE & CELLOPHANE 33 CELLOPHANE BAGS & SHEETS PRODUCE BAGS 34 POLY MESH PRODUCE HARVEST BAGS 35 CATEGORY INDEX INDICES 36 NUMERICAL INDEX A 37 NUMERICAL INDEX B Brown Paper Goods Company 3530 Birchwood Drive Waukegan, IL 60085 (800) 323-9099 www.brownpapergoods.com Page 3 BROWN PAPER GOODS TERMS & CONDITIONS Terms of Sale Freight Full freight allowed on combined shipments of 1,000 pounds or more to all states except Alaska and Hawaii. -

Making Paper from Stone

MAKING PAPER FROM STONE INNOVATIVE GREEN PRODUCTION TECHNOLOGY FROM CHINA By Xi Fang The current paper production still depends much on the exploitation of wood material, which contributes to the phenomenon of deforestation and degrading our living environment. A company in China, however, developed a revolutionary paper material made of ore powder and non- toxic resin, colloquially called stone paper. The Jiuding Environmental Paper Co. Ltd was founded in 2009 with its headquarter in Shanghai and a 70,000 m2 factory area in the beautiful Buddhist shrine under the Jiuhua Mountain. Collaborating with Chinese universities, the company has achieved the invention and development of technologies related to the production of paper based on stone. The first phase of stone paper uses mainly calcite stone as the raw material, cutting it into particles and blending it with other 10 materials. Similar to non-wood paper, the Jiuding Company is developing non-wood plank, as well, using calcium carbonate as key material. The unique technology of the Company allows a production of paper without wood, rather, with educing calcium carbonate (CaCO3) as the main raw material, together with other non-toxic excipients, through the physical method of synthesis, which reduces significantly the dependence of current paper production industry on wood and contributing to the protection of environment. Moreover, the general cost of stone paper is even lower than normal paper, and stone paper is water-proof, flexible and invulnerable in terms of physical characters. The material of rich mineral paper keeps sufficient supply and stable cost. According to the data of the company, replacing 1 ton of wood paper with stone paper, it is possible to prevent 20 trees from being cut down, saving 7480 gallons of water and 6 million BTU energy, avoiding 167 lbs solid waste, 42 lbs waste water and 236 lbs atmospheric emissions. -

14 JPN 4930 Japanese Business Culture Section 08CE Spring 2017 COURSE DESCRIPTION

14 JPN 4930 Japanese Business Culture Section 08CE Spring 2017 COURSE DESCRIPTION This course is designed for undergraduate students who wish to acquire a broader understanding of prevailing values, attitudes, behavior patterns, and communication styles in modern Japan in regard to conducting business in the future. A key to being successful in business internationally is to understand the role of culture in international business. In this class we will explore cross-cultural issues and cultural values by reading essays from the perspective of Japan itself as well as from an external view, primarily that of Western society. Mutual assumptions, unconscious strategies, and different mechanics forming barriers to communication between Japanese and non-Japanese will be investigated in order to understand how cultural and communication differences can create misunderstanding and breakdown among individuals as well as during negotiations between companies and countries. Among other topics, business etiquette, business communication, the structure and hierarchy of Japanese companies, gender issues, socializing for success in business, and strategies for creating and maintaining effective working relationships with Japanese counterparts will be discussed. We will read several case studies on Japanese/American negotiations to understand how American managers or public officials negotiated successfully with Japanese counterparts, and what issues or problems were presented during negotiation. During the semester, students are required to submit (1) current relevant newspaper, magazine, or on-line article taken from news sources such as Japanese newspapers (English version), CNBC, Nikkei Net, JETRO, Reuters, BBC, THE ECONOMIST or TIME magazine, etc. to be pre-approved and posted by the instructor on the E-Learning in Canvas Discussion Board. -

KARST-Factsheet

A little about us It only takes a couple of people to change an industry. We could kill trees too. But why should we have to? It’s possible to make paper without timber and water, without chlorine or acids, without waste, using only a third of the carbon footprint. So we did. Our paper is made of stone. It’s smoother, brighter, and more durable than traditional paper. We don’t compromise. Neither should you. We get a lot of questions about stone paper—qualities, environmental benefits, similarities to and differences from traditional wood pulp paper. These pages address all the queries you may have about our stone paper. Karst Stone Paper™ fact sheet What is Karst Stone Paper™? How is stone paper different than Producing just one ton of traditional wood pulp paper regular paper? requires around 18 tall trees and 2770 liters of water. Karst offers a range of stationery products crafted Traditional paper can only be recycled up to 7 times from stone paper. Geologists termed ‘karst’, referring Stone paper is just like regular paper, only better. and requires additional virgin fibers each time it is to a specific type of terrain resulting from the Unlike regular paper, stone paper is waterproof, tear- recycled. Natural forests are often cut and burned to dissolution of stone. The name ‘Karst’ reflects both resistant, has no ink bleed-through. Stone paper is plant non-indigenous, fast-growing trees. our products and our vision— to dissolve, rather, brighter, smoother, and more environmentally disrupt the paper industry. The need for paper isn’t responsible than regular paper. -

Japanese Business Concepts You Should Know

1 Japanese Business Concepts You Should Know Edited by Parissa Haghirian Sophia University Tokyo, Japan 2 Contents About this Book ......................................................................................... 4 The Editor ................................................................................................ 5 Japanese Business Concepts You Should Know ................................................. 6 Contributors of This Book ............................................................................ 94 Bibliography ............................................................................................ 96 Further Reading on Japanese Management .................................................... 102 3 About this Book This book is the result of one of my “Management in Japan” classes held at the Faculty of Liberal Arts at Sophia University in Tokyo. Students wrote this dictionary entries, I edited and updated them. The document is now available as a free e-book at my homepage www.haghirian.com. We hope that this book improves understanding of Japanese management and serves as inspiration for anyone interested in the subject. Questions and comments can be sent to [email protected]. Please inform the editor if you plan to quote parts of the book. Japanese Business Concepts You Should Know Edited by Parissa Haghirian First edition, Tokyo, October 2019 4 The Editor Parissa Haghirian is Professor of International Management at Sophia University in Tokyo. She lives and works in Japan since 2004 -

Eco-Frendly and High-Quality Paper Made from Stone In

ECO-FRENDLY AND HIGH-QUALITY PAPER MADE FROM STONE IN TAIWAN The Taiwan Lung Meng Technology Company (TLM), based in Tainan (Taiwan), has pioneered a process converting recycled debris from the construction industry into high- quality Stone Paper. The Stone Paper, that uses a mixture made for 80 per cent of calcium carbonate and for 20 per cent of a non-toxic resin, is not only 100% recyclable but its manufacturing process is also eco-friendly. This paper, in fact, is manufactured without the need to fell trees, without polluting water and generating harmful gaseous wastes. The process for creating the Stone Paper was developed and then patented by the Lung Meng Company in Taiwan in 1998. As soon as the export process started, this stone papermaking technology has attracted the attention of customers as an environmentally sustainable solution. The web page of the Lung Meng Company presents the main features of the Stone Paper and the fabrication process adopted. The great range of products made since 2012 shows the potential of this innovative technology. In fact, in addition to bringing great environmental benefits, the Stone Paper has other features that make it interesting for its potential uses and for consumers: It is flame-resistant, durable and waterproof. Due to the paper's durability, it can be used for making maps, charts, field notebooks, manuals and waterproof journals that will be tear and stain-resistant. It can be used for tags and labels, posters, banners and outdoor signs which will withstand weather, for packaging and wrapping, for shopping and garbage bags that are durable.