A Basic Vocabulary of Htoklibang Pwo Karen with Hpa-An, Kyonbyaw, and Proto-Pwo Karen Forms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

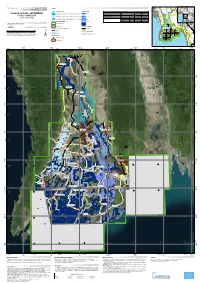

Irrawaddy Delta - MYANMAR Flooded Area Delineation 11/08/2015 11:46 UTC River R

Nepal (!Loikaw GLIDE number: N/A Activation ID: EMSR130 I Legend r n r India China e Product N.: 16IRRAWADDYDELTA, v2, English Magway a Rakhine w Bangladesh e a w l d a Vietnam Crisis Information Hydrology Consequences within the AOI on 09, 10, 11/08/2015 d Myanmar S Affected Total in AOI y Nay Pyi Taw Irrawaddy Delta - MYANMAR Flooded Area delineation 11/08/2015 11:46 UTC River R ha 428922,1 i v Laos Flooded area e ^ r S Flood - 01/08/2015 Flooded Area delineation 10/08/2015 23:49 UTC Stream Estimated population Inhabitants 4252141 11935674 it Bay of ( to Settlements Built-up area ha 35491,8 75542,0 A 10 Bago n Bengal Thailand y g Delineation Map e Flooded Area delineation 09/08/2015 11:13 UTC Lake y P Transportation Railways km 26,0 567,6 a Cambodia r i w Primary roads km 33,0 402,1 Andam an n a Gulf of General Information d Sea g Reservoir Secondary roads km 57,2 1702,3 Thailand 09 y Area of Interest ) Andam an Cartographic Information River Sea Missing data Transportation Bay of Bengal 08 Bago Tak Full color ISO A1, low resolution (100 dpi) 07 1:600000 Ayeyarwady Yangon (! Administrative boundaries Railway Kayin 0 12,5 25 50 Region km Primary Road Pathein 06 04 11 12 (! Province Mawlamyine Grid: WGS 1984 UTM Zone 46N map coordinate system Secondary Road 13 (! Tick marks: WGS 84 geographical coordinate system ± Settlements 03 02 01 ! Populated Place 14 15 Built-Up Area Gulf of Martaban Andaman Sea 650000 700000 750000 800000 850000 900000 950000 94°10'0"E 94°35'0"E 95°0'0"E 95°25'0"E 95°50'0"E 96°15'0"E 96°40'0"E 97°5'0"E N " 0 ' 5 -

De Sousa Sinitic MSEA

THE FAR SOUTHERN SINITIC LANGUAGES AS PART OF MAINLAND SOUTHEAST ASIA (DRAFT: for MPI MSEA workshop. 21st November 2012 version.) Hilário de Sousa ERC project SINOTYPE — École des hautes études en sciences sociales [email protected]; [email protected] Within the Mainland Southeast Asian (MSEA) linguistic area (e.g. Matisoff 2003; Bisang 2006; Enfield 2005, 2011), some languages are said to be in the core of the language area, while others are said to be periphery. In the core are Mon-Khmer languages like Vietnamese and Khmer, and Kra-Dai languages like Lao and Thai. The core languages generally have: – Lexical tonal and/or phonational contrasts (except that most Khmer dialects lost their phonational contrasts; languages which are primarily tonal often have five or more tonemes); – Analytic morphological profile with many sesquisyllabic or monosyllabic words; – Strong left-headedness, including prepositions and SVO word order. The Sino-Tibetan languages, like Burmese and Mandarin, are said to be periphery to the MSEA linguistic area. The periphery languages have fewer traits that are typical to MSEA. For instance, Burmese is SOV and right-headed in general, but it has some left-headed traits like post-nominal adjectives (‘stative verbs’) and numerals. Mandarin is SVO and has prepositions, but it is otherwise strongly right-headed. These two languages also have fewer lexical tones. This paper aims at discussing some of the phonological and word order typological traits amongst the Sinitic languages, and comparing them with the MSEA typological canon. While none of the Sinitic languages could be considered to be in the core of the MSEA language area, the Far Southern Sinitic languages, namely Yuè, Pínghuà, the Sinitic dialects of Hǎinán and Léizhōu, and perhaps also Hakka in Guǎngdōng (largely corresponding to Chappell (2012, in press)’s ‘Southern Zone’) are less ‘fringe’ than the other Sinitic languages from the point of view of the MSEA linguistic area. -

Water Infrastructure Development and Policymaking in the Ayeyarwady Delta, Myanmar

www.water-alternatives.org Volume 12 | Issue 3 Ivars, B. and Venot, J.-P. 2019. Grounded and global: Water infrastructure development and policymaking in the Ayeyarwady Delta, Myanmar. Water Alternatives 12(3): 1038-1063 Grounded and Global: Water Infrastructure Development and Policymaking in the Ayeyarwady Delta, Myanmar Benoit Ivars University of Köln, Germany; [email protected] Jean-Philippe Venot UMR G-EAU, IRD, Univ Montpellier, France; and Royal University of Agriculture, Phnom Penh, Cambodia; jean- [email protected] ABSTRACT: Seen as hotspots of vulnerability in the face of external pressures such as sea level rise, upstream water development, and extreme weather events but also of in situ dynamics such as increasing water use by local residents and demographic growth, deltas are high on the international science and development agenda. What emerges in the literature is the image of a 'global delta' that lends itself to global research and policy initiatives and their critique. We use the concept of 'boundary object' to critically reflect on the emergence of this global delta. We analyse the global delta in terms of its underpinning discourses, narratives, and knowledge generation dynamics, and through examining the politics of delta-oriented development and aid interventions. We elaborate this analytical argument on the basis of a 150-year historical analysis of water infrastructure development and policymaking in the Ayeyarwady Delta, paying specific attention to recent attempts at developing an Integrated Ayeyarwady Delta Strategy (IADS) and the role that the development of this strategy has played in the 'making' of the Ayeyarwady Delta as a global delta. -

World Directory of Minorities

World Directory of Minorities Asia and Oceania MRG Directory –> Myanmar/Burma –> Karen Print Page Close Window Karen Profile The term ‘Karen’ actually refers to a number of ethnic groups with Tibetan-Central Asian origins who speak 12 related but mutually unintelligible languages (‘Karenic languages’) that are part of the Tibeto- Burman group of the Sino-Tibetan family. Around 85 per cent of Karen belong either to the S’ghaw language branch, and are mostly Christian and animist living in the hills, or the Pwo section and are mostly Buddhists. The vast majority of Karen are Buddhists (probably over two-thirds), although large numbers converted to Christianity during British rule and are thought to constitute about 30 per cent among the Karen. The group encompasses a great variety of ethnic groups, such as the Karenni, Padaung (also known by some as ‘long-necks’ because of the brass coils worn by women that appear to result in the elongation of their necks), Bghai, Brek, etc. There are no reliable population figures available regarding their total numbers in Burma: a US State Department estimate for 2007 suggests there may be over 3.2 million living in the eastern border region of the country, especially in Karen State, Tenasserim Division, eastern Pegu Division, Mon State and the Irrawaddy Division. Historical context While there is some uncertainty as to the origins of the various Karen peoples, it is thought that their migration may have occurred after the arrival of the Mon – who are thought to have established themselves in the region before the start of the first millennium BCE – but before that of the Burmans sometime before the ninth century. -

Sumi Tone: a Phonological and Phonetic Description of a Tibeto-Burman Language of Nagaland

Sumi tone: a phonological and phonetic description of a Tibeto-Burman language of Nagaland Amos Benjamin Teo Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Masters by Research (by Thesis Only) December 2009 School of Languages and Linguistics The University of Melbourne Abstract Previous research on Sumi, a Tibeto-Burman language spoken in the extreme northeast of India, has found it to have three lexical tones. However, the few phonological studies of Sumi have focused mainly on its segmental phonology and have failed to provide any substantial account of the tone system. This thesis addresses the issue by providing the first comprehensive description of tone in this language. In addition to confirming three contrastive tones, this study also presents the first acoustic phonetic analysis of Sumi, looking at the phonetic realisation of these tones and the effects of segmental perturbations on tone realisation. The first autosegmental representation of Sumi tone is offered, allowing us to account for tonal phenomena such as the assignment of surface tones to prefixes that appear to be lexically unspecified for tone. Finally, this investigation presents the first account of morphologically conditioned tone variation in Sumi, finding regular paradigmatic shifts in the tone on verb roots that undergo nominalisation. The thesis also offers a cross-linguistic comparison of the tone system of Sumi with that of other closely related Kuki-Chin-Naga languages and some preliminary observations of the historical origin and development of tone in these languages are made. This is accompanied by a typological comparison of these languages with other Tibeto-Burman languages, which shows that although these languages are spoken in what has been termed the ‘Indosphere’, their tone systems are similar to those of languages spoken further to the east in the ‘Sinosphere’. -

Sino-Tibetan Numeral Systems: Prefixes, Protoforms and Problems

Sino-Tibetan numeral systems: prefixes, protoforms and problems Matisoff, J.A. Sino-Tibetan Numeral Systems: Prefixes, Protoforms and Problems. B-114, xii + 147 pages. Pacific Linguistics, The Australian National University, 1997. DOI:10.15144/PL-B114.cover ©1997 Pacific Linguistics and/or the author(s). Online edition licensed 2015 CC BY-SA 4.0, with permission of PL. A sealang.net/CRCL initiative. PACIFIC LINGUISTICS FOUNDING EDITOR: Stephen A. Wunn EDITORIAL BOARD: Malcolm D. Ross and Darrell T. Tryon (Managing Editors), Thomas E. Dutton, Nikolaus P. Himmelmann, Andrew K. Pawley Pacific Linguistics is a publisher specialising in linguistic descriptions, dictionaries, atlases and other material on languages of the Pacific, the Philippines, Indonesia and southeast Asia. The authors and editors of Pacific Linguistics publications are drawn from a wide range of institutions around the world. Pacific Linguistics is associated with the Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies at the Australian National University. Pacific Linguistics was established in 1963 through an initial grant from the Hunter Douglas Fund. It is a non-profit-making body financed largely from the sales of its books to libraries and individuals throughout the world, with some assistance from the School. The Editorial Board of Pacific Linguistics is made up of the academic staff of the School's Department of Linguistics. The Board also appoints a body of editorial advisors drawn from the international community of linguists. Publications in Series A, B and C and textbooks in Series D are refereed by scholars with re levant expertise who are normally not members of the editorial board. -

Sediment Dispersal and Accumulation Off the Ayeyarwady Delta

Marine Geology 417 (2019) 106000 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Marine Geology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/margo Sediment dispersal and accumulation off the Ayeyarwady delta – Tectonic and oceanographic controls T ⁎ Steven A. Kuehla, , Joshua Williamsa, J. Paul Liub, Courtney Harrisa, Day Wa Aungc, Danielle Tarpleya, Mary Goodwyna, Yin Yin Ayed a Virginia Institute of Marine Science, Gloucester Point, VA, USA b North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC, USA c University of Yangon, Yangon, Myanmar d Mawlamyine University, Mawlamyine, Myanmar ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Editor: Edward Anthony Recent sediment dispersal and accumulation on the Northern Andaman Sea continental shelf, off the Ayeyarwady (Irrawaddy) and Thanlwin (Salween) Rivers, are investigated using seabed, water column, and high-resolution seismic data collected in December 2017. 210Pb and 137Cs derived sediment accumulation rates − are highest (up to 10 cm y 1) in the mid-shelf region of the Martaban Depression, a basin that has formed on the eastern side of the N-S trending Sagaing fault, where rapid progradation of a muddy subaqueous delta is oc- curring. Landward of the zone of highest accumulation, in the shallow Gulf of Martaban, is a highly turbid zone where the seabed is frequently mixed to depths of ~1 m below the sediment water interface. Frequent re- suspension in this area may contribute to the formation of extensive fluid muds in the water column, and consequent re-oxidation of the shallow seabed likely reduces the carbon burial efficiency for an area where the rivers are supplying large amounts of terrestrial carbon to the ocean. Sediment cores from the Gulf of Martban have a distinctive reddish brown coloration, while x-radiographs show sedimentary structures of fine silt la- minations in mud deposits, which indicates strong tidal influences. -

Myanmar Languages | Ethnologue

7/24/2016 Myanmar Languages | Ethnologue Myanmar LANGUAGES Akeu [aeu] Shan State, Kengtung and Mongla townships. 1,000 in Myanmar (2004 E. Johnson). Status: 5 (Developing). Alternate Names: Akheu, Aki, Akui. Classi囕cation: Sino-Tibetan, Tibeto-Burman, Ngwi-Burmese, Ngwi, Southern. Comments: Non-indigenous. More Information Akha [ahk] Shan State, east Kengtung district. 200,000 in Myanmar (Bradley 2007a). Total users in all countries: 563,960. Status: 3 (Wider communication). Alternate Names: Ahka, Aini, Aka, Ak’a, Ekaw, Ikaw, Ikor, Kaw, Kha Ko, Khako, Khao Kha Ko, Ko, Yani. Dialects: Much dialectal variation; some do not understand each other. Classi囕cation: Sino-Tibetan, Tibeto-Burman, Ngwi-Burmese, Ngwi, Southern. More Information Anal [anm] Sagaing: Tamu town, 10 households. 50 in Myanmar (2010). Status: 6b (Threatened). Alternate Names: Namfau. Classi囕cation: Sino-Tibetan, Tibeto-Burman, Sal, Kuki-Chin-Naga, Kuki-Chin, Northern. Comments: Non- indigenous. Christian. More Information Anong [nun] Northern Kachin State, mainly Kawnglangphu township. 400 in Myanmar (2000 D. Bradley), decreasing. Ethnic population: 10,000 (Bradley 2007b). Total users in all countries: 450. Status: 7 (Shifting). Alternate Names: Anoong, Anu, Anung, Fuchve, Fuch’ye, Khingpang, Kwingsang, Kwinp’ang, Naw, Nawpha, Nu. Dialects: Slightly di㨽erent dialects of Anong spoken in China and Myanmar, although no reported diഡculty communicating with each other. Low inherent intelligibility with the Matwang variety of Rawang [raw]. Lexical similarity: 87%–89% with Anong in Myanmar and Anong in China, 73%–76% with T’rung [duu], 77%–83% with Matwang variety of Rawang [raw]. Classi囕cation: Sino-Tibetan, Tibeto-Burman, Central Tibeto-Burman, Nungish. Comments: Di㨽erent from Nung (Tai family) of Viet Nam, Laos, and China, and from Chinese Nung (Cantonese) of Viet Nam. -

Monitoring Rice Agriculture Across Myanmar Using Time Series Sentinel-1 Assisted by Landsat-8 and PALSAR-2

remote sensing Article Monitoring Rice Agriculture across Myanmar Using Time Series Sentinel-1 Assisted by Landsat-8 and PALSAR-2 Nathan Torbick 1,*, Diya Chowdhury 1, William Salas 1 and Jiaguo Qi 2 1 Applied Geosolutions, Newmarket, NH 03857, USA; [email protected] (D.C.); [email protected] (W.S.) 2 Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI 48823, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-603-292-1192 Academic Editors: Nicolas Baghdadi, Xiaofeng Li and Prasad S. Thenkabail Received: 22 December 2016; Accepted: 24 January 2017; Published: 1 February 2017 Abstract: Assessment and monitoring of rice agriculture over large areas has been limited by cloud cover, optical sensor spatial and temporal resolutions, and lack of systematic or open access radar. Dense time series of open access Sentinel-1 C-band data at moderate spatial resolution offers new opportunities for monitoring agriculture. This is especially pertinent in South and Southeast Asia where rice is critical to food security and mostly grown during the rainy seasons when high cloud cover is present. In this research application, time series Sentinel-1A Interferometric Wide images (632) were utilized to map rice extent, crop calendar, inundation, and cropping intensity across Myanmar. An updated (2015) land use land cover map fusing Sentinel-1, Landsat-8 OLI, and PALSAR-2 were integrated and classified using a randomforest algorithm. Time series phenological analyses of the dense Sentinel-1 data were then executed to assess rice information across all of Myanmar. The broad land use land cover map identified 186,701 km2 of cropland across Myanmar with mean out-of-sample kappa of over 90%. -

West-Central Thailand Pwo Karen Phonology1

Journal of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society JSEALS Vol. 11.1 (2018): 47-62 ISSN: 1836-6821, DOI: http://hdl.handle.net/10524/52420 University of Hawaiʼi Press WEST-CENTRAL THAILAND PWO KAREN PHONOLOGY1 Audra Phillips Payap University [email protected] Abstract West-Central Thailand Pwo Karen (Karenic, Tibeto-Burman) is one of several mutually unintelligible varieties of Pwo Karen found in Myanmar and Thailand. This paper represents an updated version of a phonological description (Phillips 2000). The study includes a comparison of the phonologies of Burmese Eastern Pwo Karen (Hpa-an and Tavoy) and the Thailand Pwo Karen varieties, West-Central Thailand Pwo Karen and Northern Pwo Karen. While the consonant inventories are similar, the vowel inventories exhibit diphthongization of some nasalized vowels. Also, some former nasalized vowels have lost their nasalization. This denasalization is most pronounced in the Burmese Eastern Pwo Karen varieties. Moreover, these varieties have either lost the two glottalized tones, or are in the process of losing them, while this process has only begun in West-Central Thailand Pwo Karen. In contrast, all six tones are present in Northern Pwo Karen. Keywords: Karenic, Pwo Karen, phonology, nasalization, diphthongization, denasalization ISO 639-3 codes: kjp, pww, pwo 1 Introduction The Pwo Karen branch of the Karenic subgroup of the Tibeto-Burman language family is comprised of several mutually unintelligible language varieties. These varieties include Western, Eastern, and Htoklibang Pwo Karen in Myanmar (Kato 2009) and West-Central Thailand Pwo Karen (WCT Pwo) and Northern Pwo Karen (N. Pwo) in Thailand (Dawkins & Phillips 2009a).2 In addition, the intelligibility status of other Pwo Karen varieties of northern Thailand, which are found in northern Tak, Lamphun, Lampang, Phrae, and Chiang Rai provinces, are not as certain (Dawkins & Phillips 2009b). -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Word Prosody And

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Word Prosody and Intonation of Sgaw Karen A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Linguistics by Luke Alexander West 2017 © Copyright by Luke Alexander West 2017 ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS Word Prosody and Intonation of Sgaw Karen by Luke Alexander West Master of Arts in Linguistics University of California, Los Angeles, 2017 Professor Sun-Ah Jun, Chair The prosodic, and specifically intonation, systems of Tibeto-Burman languages have received less attention in research than those of other families. This study investigates the word prosody and intonation of Sgaw Karen, a tonal Tibeto-Burman language of eastern Burma, and finds similarities to both closely related Tibeto-Burman languages and the more distant Sinitic languages like Mandarin. Sentences of varying lengths with controlled tonal environments were elicited from a total of 12 participants (5 male). In terms of word prosody, Sgaw Karen does not exhibit word stress cues, but does maintain a prosodic distinction between the more prominent major syllable and the phonologically reduced minor syllable. In terms of intonation, Sgaw Karen patterns like related Pwo Karen in its limited use of post-lexical tone, which is only present at Intonation Phrase (IP) boundaries. Unlike the intonation systems of Pwo Karen and Mandarin, however, Sgaw Karen exhibits downstep across its Accentual Phrases (AP), similarly to phenomena identified in Tibetan and Burmese. ii The thesis of Luke West is approved. Kie R. Zuraw Robert T. Daland Sun-Ah Jun, Committee Chair University of California, Los Angeles 2017 iii Dedication With gratitude to my committee chair Dr. -

Karenic As a Branch of Tibeto-Burman: More Evidence from Proto-Karen

Paper presented at SEALS24, organised by the Department of Myanmar Language, the University of Yangon and SOAS, University of London, in Yangon, Myanmar, May 27-31, 2014. Karenic as a Branch of Tibeto-Burman: More Evidence from Proto-Karen Theraphan Luangthongkum Department of Linguistics, Chulalongkorn University E-mail: [email protected] Abstract According to the provisional STEDT Family Tree, Karenic is a branch of Tibeto- Burman (Matisoff, 2003). Weidert, a Tibeto-Burman specialist, also states quite explicitly in his monograph, Tibeto-Burman Tonology (1987), that Karenic is a branch of Tibeto-Burman. To support the above view, 341 Proto-Karen forms reconstructed by the author based on fresh field data (two varieties of Northern Karen, four of Central Karen and four of Southern Karen) were compared with the Proto-Tibeto-Burman roots reconstructed by Benedict (1972) and/or Matisoff (2003). A summary of the findings, 14 important aspects with regard to the retentions and sound changes from Proto-Tibeto-Burman to Proto-Karen, is given. 1. Introduction Karenic is a distinct cluster of languages (Van Driem, 2001) or a branch of Tibeto- Burman (Matisoff 1991, 2003; Bradley, 1997) of the Sino-Tibetan language family. Karenic languages are spoken in the border area of Thailand and Myanmar, a long strip of land from the north to the south. Some Christian Sgaw Karen have migrated to the Andaman Islands and also to the United States of America, Europe and Australia due to the wars with the Burmese. In Myanmar, there are at least sixteen groups of the Karen: Pa-O, Lahta, Kayan, Bwe, Geko, Geba, Brek, Kayah, Yinbaw, Yintale, Manumanaw, Paku, Sgaw, Wewaw, Zayein and Pwo (Ethnologue, 2009).